1. Accounting for the forward element in foreign currency forwards

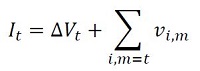

Each FX forward contract possesses a spot and forward element. The forward element represents the interest rate differential between the two currencies. Under IFRS 9 (similar to IAS 39), it is allowed to designate the entire contract or just the spot component as the hedging instrument. When designating the spot component only, the change in fair value of the forward element is recognised in OCI and accumulated in a separate component of equity. Simultaneously, the fair value of the forward points at initial recognition is amortised, most expected linearly, over the life of the hedge.

Again, this accounting treatment is only allowed in case the critical terms are aligned (similar). If at inception the actual value of the forward element exceeds the aligned value, changes in the fair value based on the aligned item will go through OCI. The difference between the fair value of the actual and aligned forward elements is recognized in P&L. In case the value of the aligned forward element exceeds the actual value at inception, changes in fair value are based on the lower of aligned versus actual and go to OCI. The remaining change of actual will be recognized in P&L.

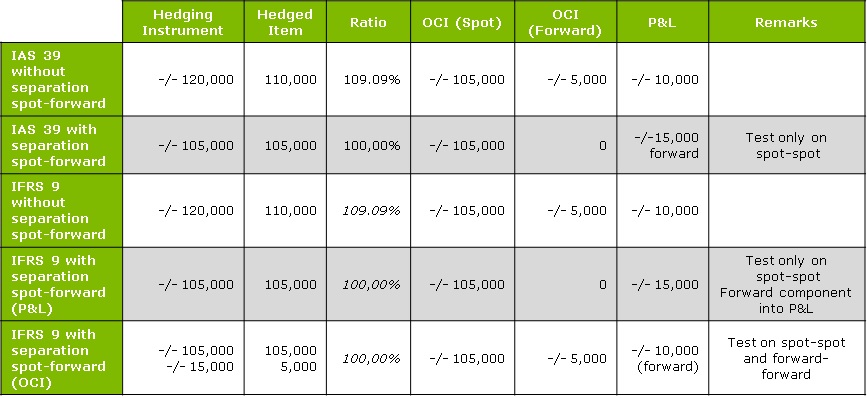

Please refer to the example below:

In this example, we consider an entity X which is hedging a future receivable with an FX forward contract.

MtM change of the forward = 105,000 (spot element) + 15,000 (forward element) = 120,000.

MtM change of the hedged item = 105,000 (spot element) + 5,000 (forward element) = 110,000.

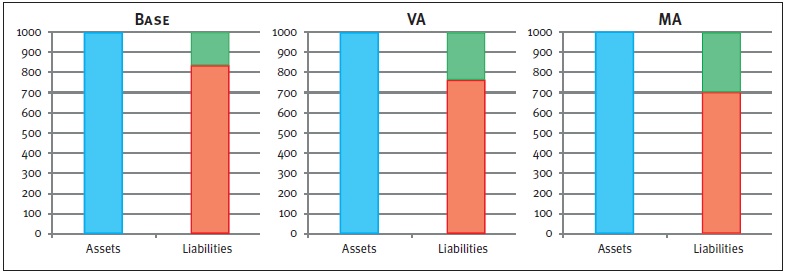

We look at alternatives under IAS39 and IFRS9 that show different accounting methods depending on the separation between the spot and forward rates.

Under IAS39 and without a spot/forward separation, the hedging instrument represents the sum of the spot and the forward element (105 000 spot + 15 000 forward= 120 000). The hedged item consisting of 105 000 spot element and 5 000 forward element and the hedge ratio being within the boundaries, the minimum between the hedging instrument and hedged item is listed as OCI, and the difference between the hedging instrument and the hedged item goes to the P&L.

However, with the spot/forward separation under IAS39, the forward component is not included in the hedging relationship and is therefore taken straight to the P&L. Everything that exceeds the movement of the hedged item is considered as an “over hedge” and will be booked in P&L.

Line 3 and 4 under IFRS9 characterise comparable registration practices than under IAS39. The changes come in when we examine line 5, where the forward element of 5 000 can be registered as OCI. In this case, a test on both the spot and the forward element is performed, compared to the previous line where only one test takes place.

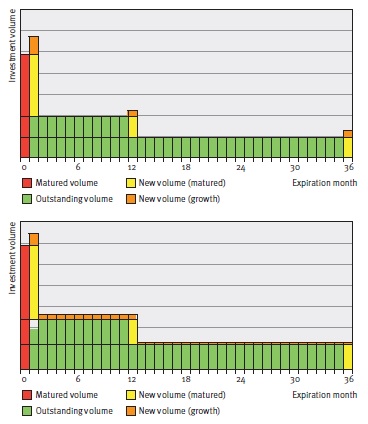

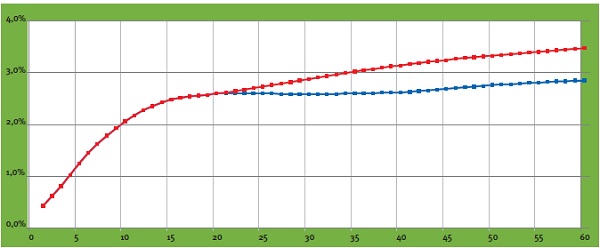

2. Rebalancing in a commodity hedge relation

Under influence of changing economic circumstances, it could be necessary to change the hedge ratio, i.e. the ratio between the amount of hedged item and the amount of hedging instruments. Under IAS 39, changes to a hedge ratio require the entity to discontinue hedge accounting and restart with a new hedging relationship that captures the desired changes. The IFRS 9 hedge accounting model allows you to refine your hedge ratio without having to discontinue the hedge relationship. This can be achieved by rebalancing.

Rebalancing is possible if there is a situation where the change in the relationship of the hedging instrument and the hedged item can be compensated by adjusting the hedge ratio. The hedge ratio can be adjusted by increasing or decreasing either the number of designated hedging instruments or hedged items.

When rebalancing a hedging relationship, an entity must update its documentation of the analysis of the sources of hedge ineffectiveness that are expected to affect the hedging relationship during its remaining term.

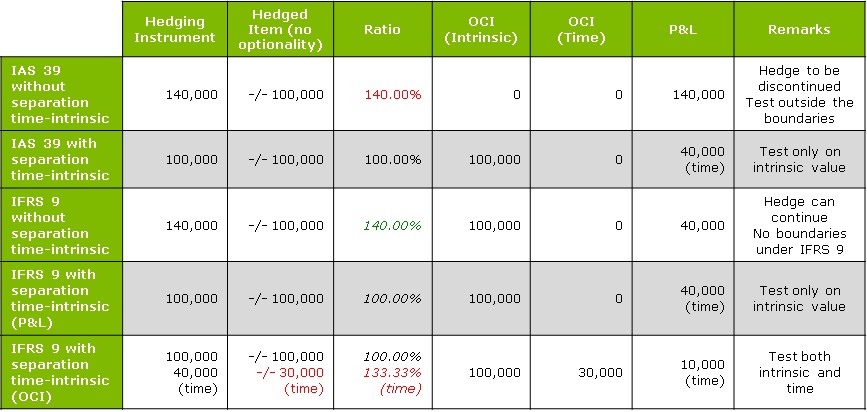

Please refer to the example below:

Entity X is hedging a forecast receivable with a FX call.

MtM change of the option = 100,000 (intrinsic value) + 40,000 (time value) = 140,000.

MtM change of the hedged item = 100,000 (intrinsic value) + 30,000 (time value) = 130,000.

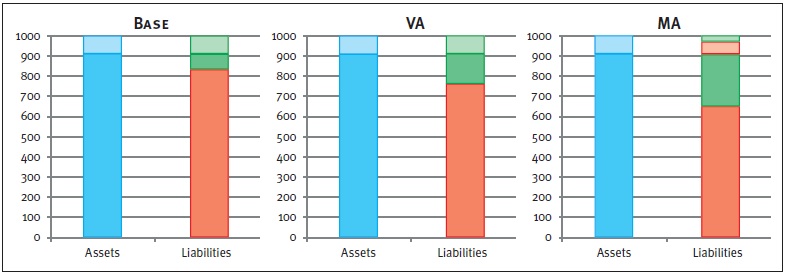

In example 3, we consider entity X to be hedging a forecast receivable via an FX call. Note that under IAS39 the hedged item cannot contain an optionality if this optionality is not present in the underlying exposure. Hence, in this example, the hedged item cannot contain any time value. The time value of 30,000 can be used under IFRS9, but only by means of a separate test (see row 5).

In line 1, we can see that without a time-intrinsic separation, the hedge relationship is no longer within the 80-125% boundary; therefore, it needs to be discontinued and the full MtM has to be booked in the P&L. In line 2, there is a time-intrinsic separation, and the 40 000 representing the time value of the option are not included in the hedge relationship, meaning that they go straight to the P&L.

Under IFRS9 with no time-intrinsic separation (line 3), the hedging relationship is accounted for in the usual manner, as the ineffectiveness boundary is not applicable, with 100 000 going representing OCI, and the over hedged 40 000 going to the P&L.

However, the time-intrinsic separation under IFRS9 in line 4 is similar to line 2 under IAS39, in which we choose to immediately remove the time value for the option from the hedging relationship. We therefore have to account for 40 000 of time value in the P&L.

In the last line, we separate between time and intrinsic values, but the time value of the option is aimed to be booked into OCI. In this case, a test on both the intrinsic and the time element is performed. We can therefore comprise 100 000 in the intrinsic OCI, 30 000 in the time OCI, and 10 000 as an over hedge in the P&L.

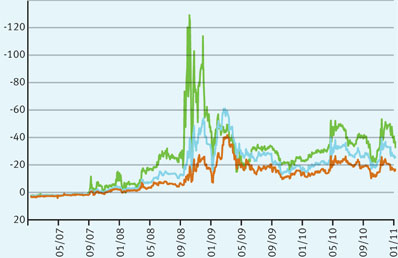

4. Cross-currency basis spread are considered a cost of hedging

The cross-currency basis spread can be defined as the liquidity premium of one currency over the other. This premium applies to exchanges of currencies in the future, e.g. a hedging instrument like an FX forward contract. If a cross currency interest rate swap is used in combination with a single currency hedged item, for which this spread is not relevant, hedge ineffectiveness could arise.

In order to cope with this mismatch, it has been decided to expand the requirements regarding the costs of hedging. Hedging costs can be seen as cost incurred to protect against unfavourable changes. Similar to the accounting for the forward element of the forward rate, an entity can exclude the cross-currency basis spread and account for it separately when designating a hedging instrument. In case a hypothetical derivative is used, the same principle applies. IFRS 9 states that the hypothetical derivative cannot include features that do not exist in the hedged item. Consequently, cross-currency basis spread cannot be part of the hypothetical derivative in the previously mentioned case. This means that hedge ineffectiveness will exist.

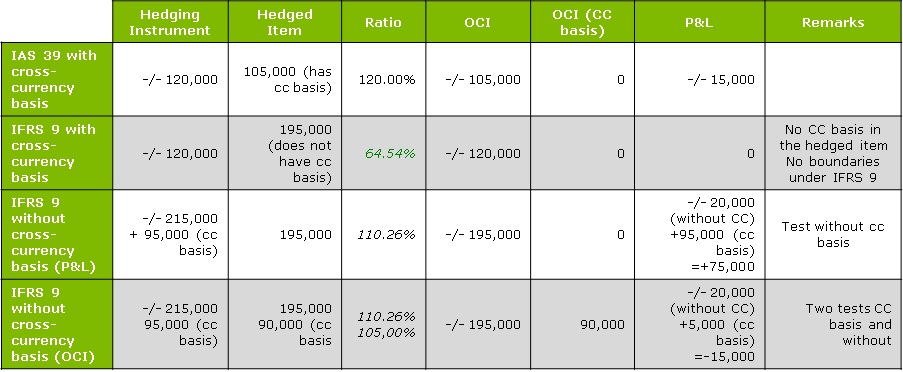

Please refer to the example below:

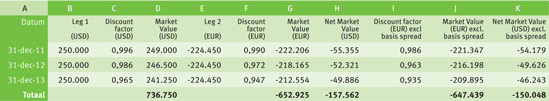

In example 4, we consider an entity X hedging a USD loan with a CCIRS.

MtM change of CCIRS = 215,000 – 95,000 (cross-currency basis) = 120,000.

MtM change hedged = 195,000 – 90,000 (cross-currency basis) = 105,000.

Under IAS39, there is only one way to account for CCIRS. The full amount of 120 000 (including the – 95 000 cross-currency basis) is considered as the hedging instrument, meaning that 105 000 can be listed as OCI and 15 000 of over hedge have to go to the P&L.

Under IFRS9, there is the option to exclude the cross-currency basis and account for it separately.

In line 2, we can see the conditions under IFRS9 when a cross-currency basis is included: the cross-currency basis cannot be comprised in the hedged item, so there is an under hedge of 75 000.

In line 3, we exclude the cross-currency basis from the test for the hedging instrument. By registering the MtM movement of 195 000 as OCI, we then account for the 95 000 of cross-currency basis, as well as -/- 20 000 of over hedge in the P&L. In line 4, the cross-currency basis is included in a separate hedge relationship – we therefore perform an extra test on the cross-currency basis (aligned versus actual values) . From the first test, -/- 195,000 is registered as OCI and -/- 20,000 (“over hedge” part) in P&L; from the cross-currency basis test 90,000 represents OCI and 5,000 has to be included in P&L.