With the introduction of CRR3, effective from January 1, 2025, the ‘extra’ guarantee on Dutch mortgages – known as the Dutch National Mortgage Guarantee (NHG) – will no longer be automatically eligible for the modelling approach. This requires institutions to apply the substitution approach instead. Although this may seem like a minor change, it can have far-reaching consequences. In this article, we provide a background on this change in the treatment of NHG and discuss the potential implications and challenges it may bring.

Introduction Dutch National Mortgage guarantee (NHG)

The Dutch National Mortgage Guarantee (NHG) serves as a safety net for borrowers and lenders of mortgage loans in the Netherlands. It is designed to provide protection in cases of financial distress caused by circumstances such as divorce, disability, or unemployment [1] [2] [3]. If these situations require the sale of the residential property and a residual debt remains after all other collection sources have been exhausted, the NHG will cover this remaining debt when contractual conditions are met1.

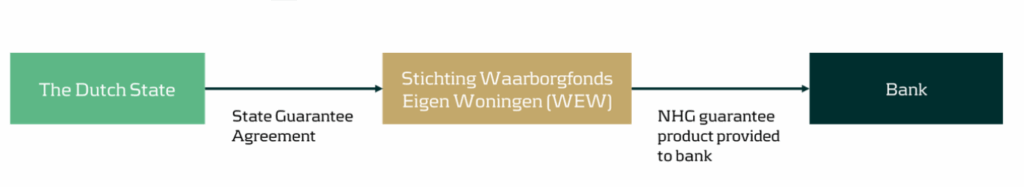

The NHG guarantee is provided by the Stichting Waarborgfonds Eigen Woning (WEW) [1] [4]. Although Stichting WEW is not state-owned, the Dutch state acts as a suretyship provider. This arrangement ensures that if Stichting WEW’s capital is insufficient to meet its guarantee claims, the state will supply unlimited interest-free loans. These loans must be repaid only after the foundation’s assets have been restored [5].

Following the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), the NHG guarantee classifies as Unfunded Credit Protection (UFCP) Credit Risk Mitigation (CRM) and should be treated accordingly.

Exposure class of Stichting WEW

As outlined in the previous text, the direct protection provider of the NHG is Stichting WEW. In the event that NHG fails to make payments, the Dutch sovereign state provides a suretyship to Stichting WEW, essentially serving as a counter-guarantee for the NHG guarantee extended by Stichting WEW.

CRR III article 4(8) [6] defines a public sector entity (PSE) as: “a non-commercial administrative body responsible to central governments, regional governments or local authorities, or to authorities that exercise the same responsibilities as regional governments and local authorities, or a non-commercial undertaking that is owned by or set up and sponsored by central governments, regional governments or local authorities, and that has explicit guarantee arrangements, and may include self-administered bodies governed by law that are under public supervision;”

Stichting WEW satisfies the definition of PSE in CRR III article 4(8), as it is a non-commercial undertaking (stichting) established2 by the central government, with an explicit guarantee arrangement from the Dutch central government. However, the CRR does not clearly define the sponsoring of the central government. Should it be determined that the sponsoring requirement is not met, Stichting WEW must instead be classified as a corporate exposure class3.

The remainder of the text assumes that Stichting WEW can be classified under the PSE exposure class as defined in CRR III article 112(c) (SA) and 147(2)(aa)(ii) (IRB). Nonetheless, the validity of the arguments throughout the following chapters remains intact, regardless of whether Stichting WEW is classified under the corporate or PSE exposure class.

Stichting WEW may not be classified as an exposure to a central government following CRR III articles 116 (SA) and 147(3)(a) (IRB), which specify that only specific public sector entities should be allocated to the central government exposure class. Given that Stichting WEW does not appear on the list published by the European Banking Authority (EBA) [7], it cannot be classified as an exposure to the central government under these articles.

There is no market consensus in the Dutch mortgage market on how to classify Stichting WEW: whether as a PSE or as a Corporate exposure. During our recently hosted roundtable discussing the implications of regulatory changes concerning NHG, participating banks indicated that it might be challenging to clearly classify Stichting WEW as a PSE due to the inconclusive regulatory guidance noted in this chapter. Banks are encouraged to engage in discussions with their Joint Supervisory Team (JST) and/or National Competent Authority (NCA) to determine the appropriate treatment of Stichting WEW.

Allowed UFCP approaches for NHG guarantees

According to CRR III article 108(3), if the AIRB approach is used for similar direct exposures to the protection provider, the UFCP modelling approach is required. In this context, similar direct exposure refers to exposure to the Stichting WEW4. With the competent authorities’ approval, the AIRB approach can be used for PSEs (and corporates), as specified in CRR III article 151(8-9). Therefore, if the AIRB approach is used for exposures to Stichting WEW, then the UFCP modelling approach is applicable. Conversely, if the SA or FIRB approach is used instead, then the UFCP substitution approach is mandatory.

Applying the effect of NHG guarantees

Under the substitution approach, the counter-guarantee provided by the Dutch central government can be recognized. CRR III article 214 states that guarantees backed by the central government may be treated as exposures within the central government exposure class, as defined in CRR III articles 112(a) (SA) and 147(2)(a) (IRB). This implies that the NHG guarantee can be classified under the central government exposure class [8]. Consequently, while capitalizing the NHG guarantee using the SA approach for the Dutch central government, it is possible, though not obligatory, to apply a 0% risk weight associated with the Dutch central government5.

If the institution employs the AIRB approach for exposures to to Stichting WEW, the modelling approach can be applied. In this scenario, risk weights for Stichting WEW and the Dutch central government (CRR article 214) are not used, as the effect of the NHG guarantee is modelled directly.

Substitution approach for banks without AIRB PSE models

For banks without AIRB models for Stichting WEW, the above argumentation does not apply, and the UFCP substitution approach for NHG presents several challenges.

The following list provides a non-exhaustive overview of these challenges:

1. Reconsideration of methodologies: Many banks model NHG separately, possibly through a specifically calibrated segment.

2. Level of application: Implementing the substitution approach within the reporting stream poses difficulties, as it requires separating the NHG-covered portion of the exposure from the uncovered portion. This could necessitate changes in data delivery and processing.

3. Changing coverage amounts over time: The NHG coverage percentage has changed from 100% to 90%, requiring at least two different implementations/calculations.

4. Unknown claimable amount: The exact amount that can be claimed is only known once the residential property is sold.

5. Loss-sharing exclusion: The substitution approach cannot incorporate the loss-sharing characteristic.

6. Mismatch between 0% substitution and actual losses of 5-10%: This is typically due to:

- Failed NHG claims, which cannot be integrated into the substitution approach.

- Discounting of cash-flows.

In summary, the substitution approach for banks without AIRB PSE models presents significant practical and methodological challenges. Effectively addressing these is essential to ensure a reliable implementation of the revised NHG treatment and maintain regulatory compliance.

Conclusion

Although the change in the CRR may seem minor at first glance, its consequences can be far-reaching. This article has outlined the key aspects of the revised NHG treatment, along with potential implications and challenges. However, it is not possible to provide a one-size-fits-all overview that fully captures the impact for every financial institution affected by this change.

If you would like to understand what the revised NHG treatment means specifically for your organization, feel free to contact our experts: Rick Stuhmer & Victor van Dongen.

Bibliography

[1] NHG, „Voorwaarden en normen [NHG conditions 2024],” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/voorwaarden-en-normen/#id-18478.

[2] NHG, „Kwijtschelding van een restschuld [NHG conditions 2024],” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/hulp-van-nhg/kwijtschelding-van-een-restschuld/.

[3] Rijksoverheid, „Nationale Hypotheek Garantie (NHG),” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/huis-kopen/vraag-en-antwoord/nationale-hypotheek-garantie-nhg.

[4] NHG, „Over de stichting [NHG annual report 2022],” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/media/1bgf13fd/nhg_jaarverslag2022-hr.pdf.

[5] Stichting Waarborgfonds Eigen Woningen, „Memorie van toelichting bij de Wet herziening eigendomsgrenzen 2023, onderdeel 1477577. Rijksfinanciën.,” 2023. [Online]. Available here.

[6] European Parliament and European Council, „Amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards requirements for credit risk, credit valuation adjustment risk, operational risk, market risk and the output floor,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401623.

[7] European Banking Authority, „Lists for the calculation of capital requirements for credit risk,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.eba.europa.eu/activities/supervisory-convergence/supervisory-disclosure/rules-and-guidance.

[8] Nauta Dutilh, „Toelaatbaarheid Nationale Hypotheek Garantie als kredietprotectie onder de CRR,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/media/rhkhtqbx/nhg-memorandum-over-crr-toelaatbaarheid-31-maart-2020-pdf.pdf

[9] Stichting Waarborgfonds Eigen Woningen, „Statuten NHG,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/media/4vvcjw4p/statuten-wew-per-23-december-2019.pdf