According to Constant Thoolen, global head of financial risk at ING, the Accelerating Think Forward strategy, an updated version of the Think Forward strategy that they just call ATF, comprises several different elements.

"Standardization is a very important one. And from standardization comes scalability and comparability. To facilitate this standardization within the financial risk management team, and thus achieve the required level of efficiency, as a bank we first had to make substantial investments so we could reap greater cost savings further down the road."

And how exactly did ING translate this into financial risk management?

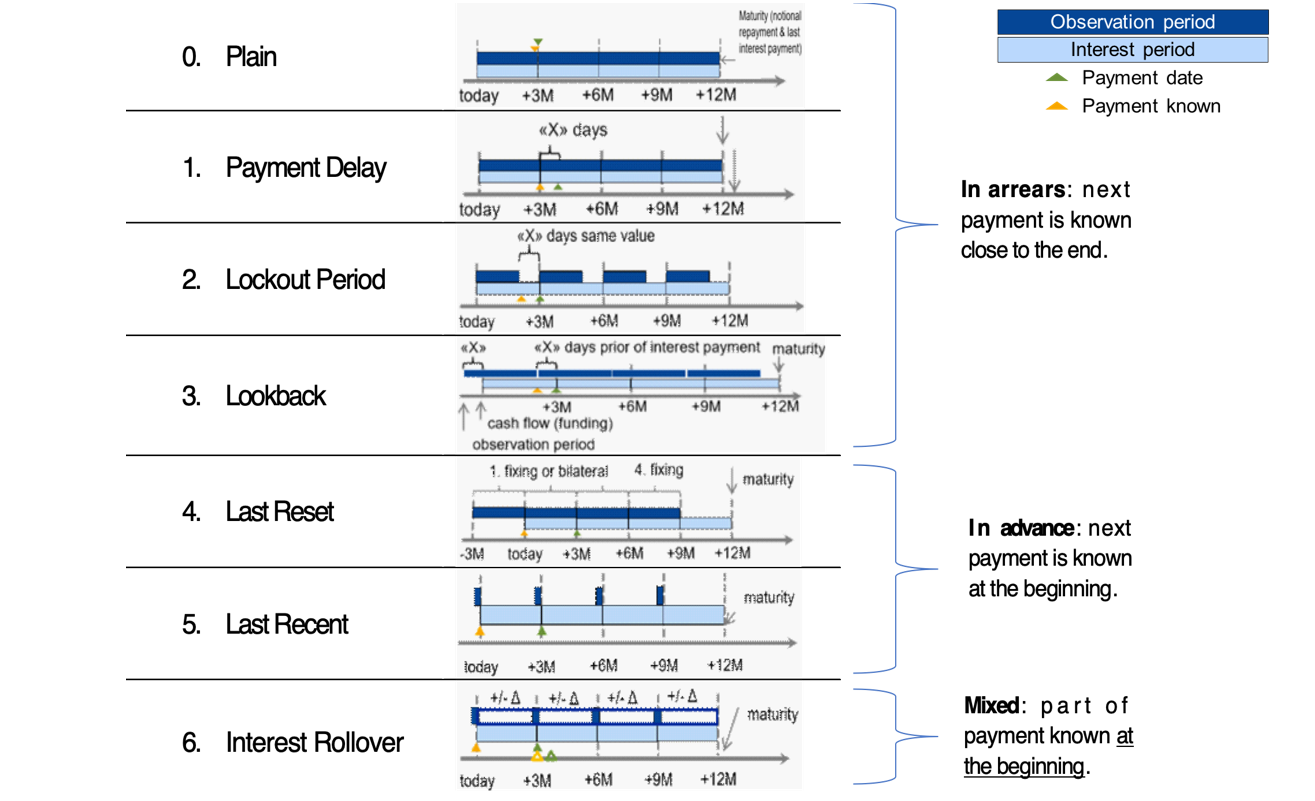

Thoolen: "Obviously, there are different facets to that risk, which permeates through all business lines. The interest rate risk in the banking book, or IRRBB, is a very important part of this. Alongside the interest rate risk in trading activities, the IRRBB represents an important risk for all business lines. Given the importance of this type of risk, and the changing regulatory complexion, we decided to start up an internal IRRBB program."

So the challenge facing the bank was how to develop a consistent framework in benchmarking and reporting the interest rate risk?

"The ATF strategy has set requirements for the consistency and standardization of tooling," explains Gilbert van Iersel, head of financial risk analysis. "On the one hand, our in-house QRM program ties in with this. We are currently rolling out a central system for our ALM activities, such as analyses and risk measurements—not only from a risk perspective but from a finance one too. Within the context of the IRRBB program, we also started to apply this level of standardization and consistency throughout the risk-management framework and the policy around it. We’re doing so by tackling standardization in terms of definitions, such as: what do we understand by interest rate risk, and what do benchmarks like earnings-at-risk or NII-at-risk actually mean? It’s all about how we measure and what assumptions we should make."

What role did international regulations play in all this?

Van Iersel: "An important one. The whole thing was strengthened by new IRRBB guidelines published by the EBA in 2015. It reconciled the ATF strategy with external guidelines, which prompted us to start up the IRRBB program."

So regulations served as a catalyst?

Thoolen: "Yes indeed. But in addition to serving as a foothold, the regulations, along with many changes and additional requirements in this area, also posed a challenge. Above all, it remains in a state of flux, thanks to Basel, the EBA, and supervision by the ECB. On the one hand, it’s true that we had expected the changes, because IRRBB discussions had been going on for some time. On the other hand, developments in the regulatory landscape surrounding IRRBB followed one another quite quickly. This is also different from the implementation of Basel II or III, which typically require a preparation and phasing-in period of a few years. That doesn’t apply here because we have to quickly comply with the new guidelines."

Did the European regulations help deliver the standardization that ING sought as an international bank?

Thoolen: "The shift from local to European supervision probably increased our need for standardization and consistency. We had national supervisors in the relevant countries, each supervising in their own way, with their own requirements and methodologies. The ECB checked out all these methodologies and created best practices on what they found. Now we have to deal with regulations that take in all Eurozone countries, which are also countries in which ING is active. Consequently, we are perfectly capable of making comparisons between the implementation of the ALM policy in the different countries. Above all, the associated risks are high on the agenda of policymakers and supervisors."

Van Iersel: "We have also used these standards in setting up a central treasury organization, for example, which is also complementary to the consistency and standardization process."

Thoolen: "But we’d already set the further integration of the various business units in motion, before the new regulations came into force. What’s more, we still have to deal with local legislation in the countries in which we operate outside Europe, such as Australia, Singapore, and the US. Our ideal world would be one in which we have one standard for our calculations everywhere."

What changed in the bank’s risk appetite as a result of this changing environment and the new strategy?

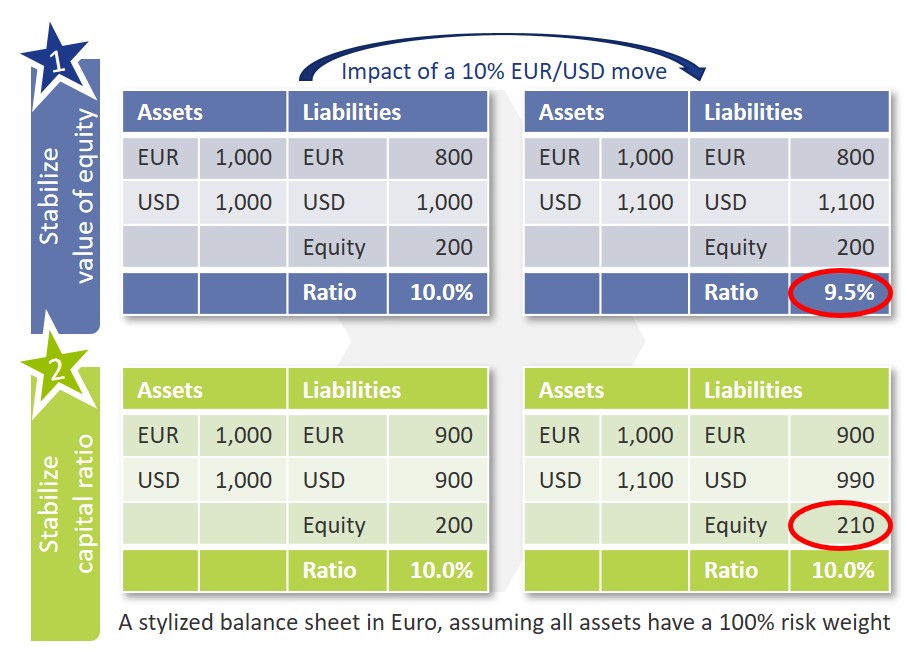

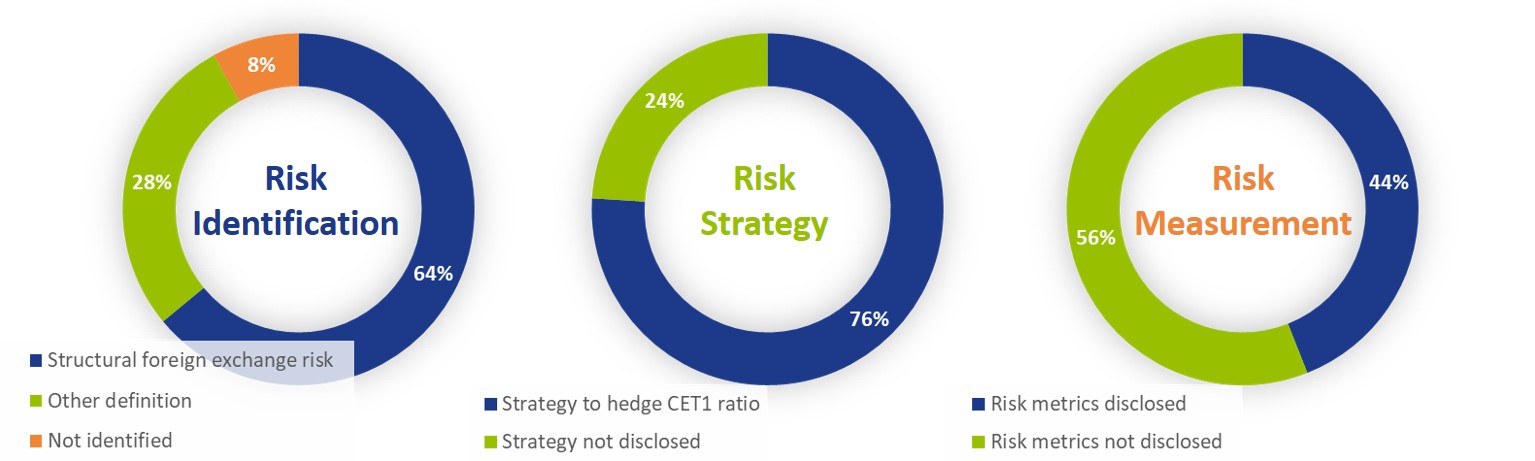

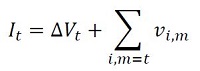

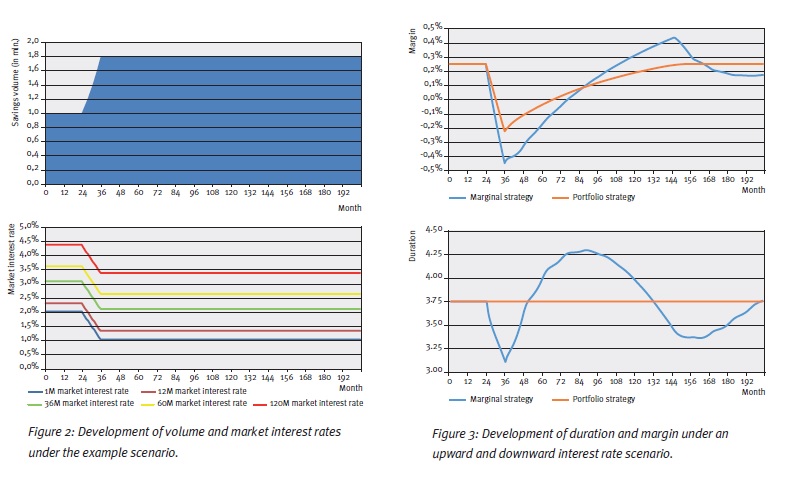

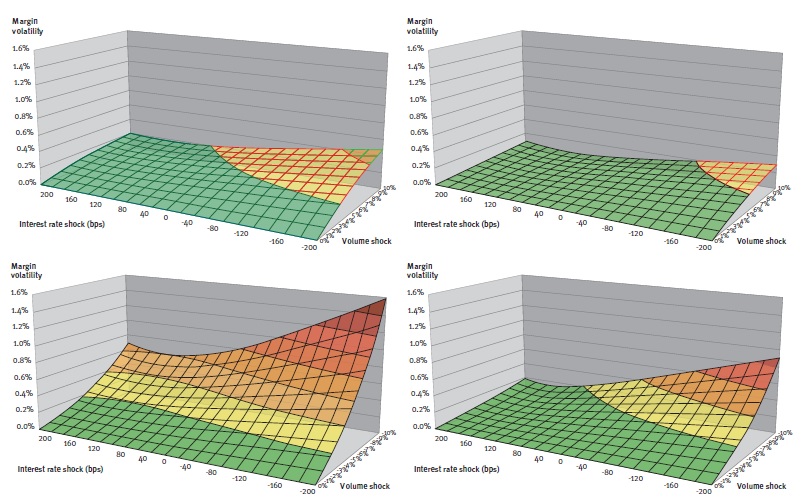

Van Iersel: "Based on newly defined benchmarks, we’ve redefined and shaped our risk appetite as a component part of the strategic program. In the risk appetite process we’ve clarified the difference between how ING wants to manage the IRRBB internally and how the regulator views the type of risk. As a bank, you have to comply with the so-called standard outlier test when it comes to the IRRBB. The benchmark commonly employed for this is the economic value of equity, which is value-based. Within the IRRBB, you can look at the interest rate risk from a value or an income perspective. Both are important, but they occasionally work against one another too. As a bank, we’ve made a choice between them. For us, a constant stream of income was the most important benchmark in defining our interest rate risk strategy, because that’s what is translated to the bottom line of the results that we post. Alongside our internal decision to focus more closely on income and stabilize it, the regulator opted to take a mainly value-based approach. We have explicitly incorporated this distinction in our risk appetite statements. It’s all based on our new strategy; in other words, what we are striving for as a bank and what will be the repercussions for our interest rate risk management. It’s from there that we define the different risk benchmarks."

Which other types of risk does the bank look at and how do they relate to the interest rate risk?

Van Iersel: “From the financial risk perspective, you also have to take into account aspects like credit spreads, changes in the creditworthiness of counterparties, as well as market-related risks in share prices and foreign exchange rates. Given that all these collectively influence our profitability and solvency position, they are also reflected in the Core Tier I ratio. There is a clear link to be seen there between the risk appetite for IRRBB and the overall risk appetite that we as a bank have defined. IRRBB is a component part of the whole, so there’s a certain amount of interaction between them to be considered; in other words, how does the interest rate risk measure up to the credit risk? On top of that, you have to decide where to deploy your valuable capacity. All this has been made clearer in this program.”

Does this mean that every change in the market can be accommodated by adjusting the risk appetite?

Thoolen: “Changing behavior can indeed influence risks and change the risk appetite, although not necessarily. But it can certainly lead to a different use of risk. Moreover, IFRS 9 has changed the accounting standards. Because the Core Tier 1 ratio is based on the accounting standard, these IFRS 9 changes determine the available capital too. If IFRS 9 changes the playing field, it also exerts an influence on certain risk benchmarks.”

In addition to setting up a consistent framework, the standardization of the models used by the different parts of ING was also important. How does ING approach the selection and development of these models?

Thoolen: “With this in mind, we’ve set up a structure with the various business units that we collaborate with from a financial risk perspective. We pay close attention to whether a model is applicable in the environment in which it’s used. In other words, is it a good fit with what’s happening in the market, does it cover all the risks as you see them, and does it have the necessary harmony with the ALM system? In this way, we want to establish optimum modeling for savings or the repayment risk of mortgages, for example.”

But does that also work for an international bank with substantial portfolios in very different countries?

Thoolen: “While there is model standardization, there is no market standardization. Different countries have their own product combinations and, outside the context of IRRBB, have to comply with regulations that differ from other countries. A savings product in the Netherlands will differ from a savings product in Belgium, for example. It’s difficult to define a one-size-fits-all model because the working of one market can be much more specific than another—particularly when it comes to regulations governing retail and wholesale. This sometimes makes standardization more difficult to apply. The challenge lies in the fact that every country and every market is specific, and the differences have to be reconciled in the model.”

Van Iersel: “The model was designed to measure risks as well as possible and to support the business to make good decisions. Having a consistent risk appetite framework can also make certain differences between countries or activities more visible. In Australia, for example, many more floating-rate mortgages are sold than here in the Netherlands, and this alters the sensitivity of the bank’s net interest income when the interest rate changes. Risk appetite statements must facilitate such differences.”

To what extent does the use of machine learning models lead to validation issues?

“Seventy to eighty percent of what we model and validate within the bank is bound by regulation – you can't apply machine learning to that. The kind of machine learning that is emerging now is much more on the business side – how do you find better customers, how do you get cross-selling? You need a framework for that; if you have a new machine learning model, what risks do you see in it and what can you do about it? How do you make sure your model follows the rules? For example, there is a rule that you can't refuse mortgages based on someone's zip code, and in the traditional models that’s well in sight. However, with machine learning, you don't really see what's going on ‘under the hood’. That's a new risk type that we need to include in our frameworks. Another application is that we use our own machine learning models as challenger models for those we get delivered from modeling. This way we can see whether it results in the same or other drivers, or we get more information from the data than the modelers can extract.”

Thoolen: “But opting for a single ALM system imposes this model standardization on you and ensures that, once it’s integrated, it will immediately comply with many conditions. The process is still ongoing, but it’s a good fit with the standardization and consistency that we’re aiming for.”

In conjunction with the changing regulatory environment, the Accelerating Think Forward Strategy formed the backdrop for a major collaboration with Zanders: the IRRBB project. In the context of this project, Zanders researched the extent to which the bank’s interest rate risk framework complied with the changing regulations. The framework also assessed ING’s new interest rate risk benchmarks and best practices. Based on the choices made by the bank, Zanders helped improve and implement the new framework and standardized models in a central risk management system.