Calibrating deposit models: Using historical data or forward-looking information?

Historical data is losing its edge. How can banks rely on forward-looking scenarios to future-proof non-maturing deposit models?

After a long period of negative policy rates within Europe, the past two years marked a period with multiple hikes of the overnight rate by central banks in Europe, such as the European Central Bank (ECB), in an effort to combat the high inflation levels in Europe. These increases led to tumult in the financial markets and caused banks to adjust the pricing of consumer products to reflect the new circumstances. These developments have given rise to a variety of challenges in modeling non-maturing deposits (NMDs). While accurate and robust models for non-maturing deposits are now more important than ever. These models generally consist of multiple building blocks, which together provide a full picture on the expected portfolio behavior. One of these building blocks is the calibration approach for parametrizing the relevant model elements, which is covered in this blog post.

One of the main puzzles risk modelers currently face is the definition of the expected repricing profile of non-maturing deposits. This repricing profile is essential for proper risk management of the portfolio. Moreover, banks need to substantiate modeling choices and subsequent parametrization of the models to both internal and external validation and regulatory bodies. Traditionally, banks used historically observed relationships between behavioral deposit components and their drivers for the parametrization. Because of the significant change in market circumstances, historical data has lost (part of) its forecasting power. As an alternative, many banks are now considering the use of forward-looking scenario analysis instead of, or in addition to, historical data.

The problem with using historical observations

In many European markets, the degree to which customer deposit rates track market rates (repricing) has decreased over the last decade. Repricing first decreased because banks were hesitant to lower rates below zero. And currently we still observe slower repricing when compared to past rising interest cycles, since interest rate hikes were not directly reflected in deposit rates. Therefore, the long period of low and even negative interest rates creates a bias in the historical data available for calibration, making the information less representative. Especially since the historical data does not cover all parts of the economic cycle. On the other hand, the historical data still contains relevant information on client and pricing behavior, such that fully ignoring observed behavior also does not seem sensible.

Therefore, to overcome these issues, Risk and ALM managers should analyze to what extent the historically repricing behavior is still representative for the coming years and whether it aligns with the banks’ current pricing strategy. Here, it could be beneficial for banks to challenge model forecasts by expectations following from economic rationale. Given the strategic relevance of the topic, and the impact of the portfolio on the total balance sheet, the bank’s senior management is typically highly involved in this process.

Improving models through forward looking information

Common sense and understanding deposit model dynamics are an integral part of the modeling process. Best practice deposit modeling includes forming a comprehensive set of possible (interest rate) scenarios for the future. To create a proper representation of all possible future market developments, both downward and upward scenarios should be included. The slope of the interest rate scenarios can be adjusted to reflect gradual changes over time, or sudden steepening or flattening of the curve. Pricing experts should be consulted to determine the expected deposit rate developments over time for each of the interest rate scenarios. Deposit model parameters should be chosen in such a way that its estimations on average provide the best fit for the scenario analysis.

When going through this process in your organization, be aware that the effects of consulting pricing experts go both ways. Risk and ALM managers will improve deposit models by using forward-looking business opinions and the business’ understanding of the market will improve through model forecasts.

Trying to define the most suitable calibration approach for your NMD model?

Would you like to know more about the challenges related to the calibration of NMD models based on historical data? Or would you like a comprehensive overview of the relevant considerations when applying forward-looking information in the calibration process?

Read our whitepaper on this topic: 'A comprehensive overview of deposit modelling concepts'

Basel IV and External Credit Ratings

Explore how Basel IV reforms and enhanced due diligence requirements will transform regulatory capital assessments for credit risk, fostering a more resilient and informed financial sector.

The Basel IV reforms, which are set to be implemented on 1 January 2025 via amendments to the EU Capital Requirement Regulation, have introduced changes to the Standardized Approach for credit risk (SA-CR). The Basel framework is implemented in the European Union mainly through the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR3) and Capital Requirements Directive (CRD6). The CRR3 changes are designed to address shortcomings in the existing prudential standards, by among other items, introducing a framework with greater risk sensitivity and reducing the reliance on external ratings. Action by banks is required to remain compliant with the CRR. Overall, the share of RWEA derived through an external credit rating in the EU-27 remains limited, representing less than 10% of the total RWEA under the SA with the CRR.

Introduction

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) identified the excessive dependence on external credit ratings as a flaw within the Standardised Approach (SA), observing that firms frequently used these ratings to compute Risk-Weighted Assets (RWAs) without adequately understanding the associated risks of their exposures. To address this issue, regulators have implemented changes aimed to reduce the mechanical reliance on external credit ratings and to encourage firms to use external credit ratings in a more informed manner. The objective is to diminish the chances of underestimating financial risks in order to further build a more resilient financial industry. Overall, the share of Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) derived through an external credit rating remains limited, and in Europe it represents less than 10% of the total RWA under the SA.

The concept of due diligence is pivotal in the regulatory framework. It refers to the rigorous process financial institutions are expected to undertake to understand and assess the risks associated with their exposures fully. Regulators promote due diligence to ensure that banks do not solely rely on external assessments, such as credit ratings, but instead conduct their own comprehensive analysis.

The due diligence is a process performed by banks with the aim of understanding the risk profile and characteristics of their counterparties at origination and thereafter on a regular basis (at least annually). This includes assessing the appropriateness of risk weights, especially when using external ratings. The level of due diligence should match the size and complexity of the bank's activities. Banks must evaluate the operating and financial performance of counterparties, using internal credit analysis or third-party analytics as necessary, and regularly access counterparty information. Climate-related financial risks should also be considered, and due diligence must be conducted both at the solo entity level and consolidated level.

Banks must establish effective internal policies, processes, systems, and controls to ensure correct risk weight assignment to counterparties. They should be able to prove to supervisors that their due diligence is appropriate. Supervisors are responsible for reviewing these analyses and taking action if due diligence is not properly performed.

Banks should have methodologies to assess credit risk for individual borrowers and at the portfolio level, considering both rated and unrated exposures. They must ensure that risk weights under the Standardised Approach reflect the inherent risk. If a bank identifies that an exposure, especially an unrated one, has higher inherent risk than implied by its assigned risk weight, it should factor this higher risk into its overall capital adequacy evaluation.

Banks need to ensure they have an adequate understanding of their counterparties’ risk profiles and characteristics. The diligent monitoring of counterparties is applicable to all exposures under the SA. Banks would need to take reasonable and adequate steps to assess the operating and financial condition of each counterparty.

Rating System

The external credit assessment institutions (ECAIs) are credit rating agencies recognised by National supervisors. The External Credit ECAIs play a significant role in the SA through the mapping of each of their credit assessments to the corresponding risk weights. Supervisors will be responsible for assigning an eligible ECAI’s credit risk assessments to the risk weights available under the SA. The mapping of credit assessments should reflect the long-term default rate.

Exposures to banks, exposures to securities firms and other financial institutions and exposures to corporates will be risk-weighted based on the following hierarchy External Credit Risk Assessment Approach (ECRA) and the Standardised Credit Risk Assessment Approach (SCRA).

ECRA: Used in jurisdictions allowing external ratings. If an external rating is from an unrecognized or non-nominated ECAI, the exposure is considered unrated. Also, banks must perform due diligence to ensure ratings reflect counterparty creditworthiness and assign higher risk weights if due diligence reveals greater risk than the rating suggests.

SCRA: Used where external ratings are not allowed. Applies to all bank exposures in these jurisdictions and unrated exposures in jurisdictions allowing external ratings. Banks classify exposures into three grades:

- Grade A: Adequate capacity to meet obligations in a timely manner.

- Grade B: Substantial credit risk, such as repayment capacities that are dependent on stable or favourable economic or business conditions.

- Grade C: Higher credit risk, where the counterparty has material default risks and limited margins of safety

The CRR Final Agreement includes a new article (Article 495e) that allows competent authorities to permit institutions to use an ECAI credit assessment assuming implicit government support until December 31, 2029, despite the provisions of Article 138, point (g).

In cases where external credit ratings are used for risk-weighting purposes, due diligence should be used to assess whether the risk weight applied is appropriate and prudent.

If the due diligence assessment suggests an exposure has higher risk characteristics than implied by the risk weight assigned to the relevant Credit Quality Step (CQS) of an exposure, the bank would assign the risk weight at least one higher than the CQS indicated by the counterparty’s external credit rating.

Criticisms to this approach are:

- Banks are mandated to use nominated ECAI ratings consistently for all exposures in an asset class, requiring banks to carry out a due diligence on each and every ECAI rating goes against the principle of consistent use of these ratings.

- When banks apply the output floor, ECAI ratings act as a backstop to internal ratings. In case the due diligence would imply the need to assign a high-risk weight, the output floor could no longer be used consistently across banks to compare capital requirements.

Implementation Challenges

The regulation requires the bank to conduct due diligence to ensure a comprehensive understanding, both at origination and on a regular basis (at least annually), of the risk profile and characteristics of their counterparties. The challenges associated with implementing this regulation can be grouped into three primary categories: governance, business processes, and systems & data.

Governance

The existing governance framework must be enhanced to reflect the new responsibilities imposed by the regulation. This involves integrating the due diligence requirements into the overall governance structure, ensuring that accountability and oversight mechanisms are clearly defined. Additionally, it is crucial to establish clear lines of communication and decision-making processes to manage the new regulatory obligations effectively.

Business Process

A new business process for conducting due diligence must be designed and implemented, tailored to the size and complexity of the exposures. This process should address gaps in existing internal thresholds, controls, and policies. It is essential to establish comprehensive procedures that cover the identification, assessment, and monitoring of counterparties' risk profiles. This includes setting clear criteria for due diligence, defining roles and responsibilities, and ensuring that all relevant staff are adequately trained.

Systems & Data

The implementation of the regulation requires access to accurate and comprehensive data necessary for the rating system. Challenges may arise from missing or unavailable data, which are critical for assessing counterparties' risk profiles. Furthermore, reliance on manual solutions may not be feasible given the complexity and volume of data required. Therefore, it is imperative to develop robust data management systems that can capture, store, and analyse the necessary information efficiently. This may involve investing in new technology and infrastructure to automate data collection and analysis processes, ensuring data integrity and consistency.

Overall, addressing these implementation challenges requires a coordinated effort across the organization, with a focus on enhancing governance frameworks, developing comprehensive business processes, and investing in advanced systems and data management solutions.

How can Zanders help?

As a trusted advisor, we built a track record of implementing CRR3 throughout a heterogeneous group of financial institutions. This provides us with an overview of how different entities in the industry deal with the different implementation challenges presented above.

Zanders has been engaged to provide project management for these Basel IV implementation projects. By leveraging the expertise of Zanders' subject matter experts, we ensure an efficient and insightful gap analysis tailored to your bank's specific needs. Based on this analysis, combined with our extensive experience, we deliver customized strategic advice to our clients, impacting multiple departments within the bank. Furthermore, as an independent advisor, we always strive to challenge the status quo and align all stakeholders effectively.

In-depth Portfolio Analysis: Our initial step involves conducting a thorough portfolio scan to identify exposures to both currently unrated institutions and those that rely solely on government ratings. This analysis will help in understanding the extent of the challenge and planning the necessary adjustments in your credit risk framework.

Development of Tailored Models: Drawing from our extensive experience and industry benchmarks, Zanders will collaborate with your project team to devise a range of potential solutions. Each solution will be detailed with a clear overview of the required time, effort, potential impact on Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA), and the specific steps needed for implementation. Our approach will ensure that you have all the necessary information to make informed strategic decisions.

Robust Solutions for Achieving Compliance: Our proprietary Credit Risk Suite cloud platform offers banks robust tools to independently assess and monitor the credit quality of corporate and financial exposures (externally rated or not) as well as determine the relevant ECRA and SCRA ratings.

Strategic Decision-Making Support: Zanders will support your Management Team (MT) in the decision-making process by providing expert advice and impact analysis for each proposed solution. This support aims to equip your MT with the insights needed to choose the most appropriate strategy for your institution.

Implementation Guidance: Once a decision has been made, Zanders will guide your institution through the specific actions required to implement the chosen solution effectively. Our team will provide ongoing support and ensure that the implementation is aligned with both regulatory requirements and your institution’s strategic objectives.

Continuous Adaptation and Optimization: In response to the dynamic regulatory landscape and your bank's evolving needs, Zanders remains committed to advising and adjusting strategies as needed. Whether it's through developing an internal rating methodology, imposing new lending restrictions, or reconsidering business relations with unrated institutions, we ensure that your solutions are sustainable and compliant.

Independent and Innovative Thinking: As an independent advisor, Zanders continuously challenges the status quo, pushing for innovative solutions that not only comply with regulatory demands but also enhance your competitive edge. Our independent stance ensures that our advice is unbiased and wholly in your best interest.

By partnering with Zanders, you gain access to a team of dedicated professionals who are committed to ensuring your successful navigation through the regulatory complexities of Basel IV and CRR3. Our expertise and tailored approaches enable your institution to manage and mitigate risks efficiently while aligning with the strategic goals and operational realities of your bank. Reach out to Tim Neijs or Marco Zamboni for further comments or questions.

REFERENCE

[1] BCBS, The Basel Framework, Basel https://www.bis.org/basel_framework

[2] Regulation (EU) No 575/2013

[3] Directive 2013/36/EU

[4] EBA Roadmap on strengthening the prudential framework

[5] EBA REPORT ON RELIANCE ON EXTERNAL CREDIT RATINGS

Regulatory exemptions during extreme market stresses: EBA publishes final RTS on extraordinary circumstances for continuing the use of internal models

Covid-19 exposed flaws in banks’ risk models, prompting regulatory exemptions, while new EBA guidelines aim to identify and manage future extreme market stresses.

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered unprecedented market volatility, causing widespread failures in banks' internal risk models. These backtesting failures threatened to increase capital requirements and restrict the use of advanced models. To avoid a potentially dangerous feedback loop from the lower liquidity, regulators responded by granting temporary exemptions for certain pandemic-related model exceptions. To act faster to future crises and reduce unreasonable increases to banks’ capital requirements, more recent regulation directly comments on when and how similar exemptions may be imposed.

Although FRTB regulation briefly comments on such situations of market stress, where exemptions may be imposed for backtesting and profit and loss attribution (PLA), it provides very little explanation of how banks can prove to the regulators that such a scenario has occurred. On 28th June, the EBA published its final draft technical standards on extraordinary circumstances for continuing the use of internal models for market risk. These standards discuss the EBA’s take on these exemptions and provide some guidelines on which indicators can be used to identify periods of extreme market stresses.

Background and the BCBS

In the Basel III standards, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) briefly comment on rare occasions of cross-border financial market stress or regime shifts (hereby called extreme stresses) where, due to exceptional circumstances, banks may fail backtesting and the PLA test. In addition to backtesting overages, banks often see an increasing mismatch between Front Office and Risk P&L during periods of extreme stresses, causing trading desks to fail PLA.

The BCBS comment that one potential supervisory response could be to allow the failing desks to continue using the internal models approach (IMA), however only if the banks models are updated to adequately handle the extreme stresses. The BCBS make it clear that the regulators will only consider the most extraordinary and systemic circumstances. The regulation does not, however, give any indication of what analysis banks can provide as evidence for the extreme stresses which are causing the backtesting or PLA failures.

The EBA’s standards

The EBA’s conditions for extraordinary circumstances, based on the BCBS regulation, provide some more guidance. Similar to the BCBS, the EBA’s main conditions are that a significant cross-border financial market stress has been observed or a major regime shift has taken place. They also agree that such scenarios would lead to poor outcomes of backtesting or PLA that do not relate to deficiencies in the internal model itself.

To assess whether the above conditions have been met, the EBA will consider the following criteria:

- Analysis of volatility indices (such as the VIX and the VSTOXX), and indicators of realised volatilities, which are deemed to be appropriate to capture the extreme stresses,

- Review of the above volatility analysis to check whether they are comparable to, or more extreme than, those observed during COVID-19 or the global financial crisis,

- Assessment of the speed at which the extreme stresses took place,

- Analysis of correlations and correlation indicators, which adequately capture the extreme stresses, and whether a significant and sudden change of them occurred,

- Analysis of how statistical characteristics during the period of extreme stresses differ to those during the reference period used for the calibration of the VaR model.

The granularity of the criteria

The EBA make it clear that the standards do not provide an exhaustive list of suitable indicators to automatically trigger the recognition of the extreme stresses. This is because they believe that cases of extreme stresses are very unique and would not be able to be universally captured using a small set of prescribed indicators.

They mention that defining a very specific set of indicators would potentially lead to banks developing automated or quasi-automated triggering mechanisms for the extreme stresses. When applied to many market scenarios, this may lead to a large number of unnecessary triggers due the specificity of the prescribed indicators. As such, the EBA advise that the analysis should take a more general approach, taking into consideration the uniqueness of each extreme stress scenario.

Responses to questions

The publication also summarises responses to the original Consultation Paper EBA/CP/2023/19. The responses discuss several different indicators or factors, on top of the suggested volatility indices, that could be used to identify the extreme stresses:

- The responses highlight the importance of correlation indicators. This is because stress periods are characterised by dislocations in the market, which can show increased correlations and heightened systemic risk.

- They also mention the use of liquidity indicators. This could include jumps of the risk-free rates (RFRs) or index swap (OIS) indicators. These liquidity indicators could be used to identify regime shifts by benchmarking against situations of significant cross-border market stress (for example, a liquidity crisis).

- Unusual deviations in the markets may also be strong indicators of the extreme stresses. For example, there could be a rapid widening of spreads between emerging and developed markets triggered by regional debt crisis. Unusual deviations between cash and derivatives markets or large difference between futures/forward and spot prices could also indicate extreme stresses.

- They suggest that restrictions on trading or delivery of financial instruments/commodities may be indicative of extreme stresses. For example, the restrictions faced by the Russian ruble due to the Russia-Ukraine war.

- Finally, the responses highlighted that an unusual amount of backtesting overages, for example more than 2 in a month, could also be a useful indicator.

Zanders recommends

It’s important that banks are prepared for potential extreme stress scenarios in the future. To achieve this, we recommend the following:

- Develop a holistic set of indicators and metrics that capture signs of potential extreme stresses,

- Use early warning signals to preempt potential upcoming periods of stress,

- Benchmark the indicators and metrics against what was observed during the great financial crisis and Covid-19,

- Create suitable reporting frameworks to ensure the knowledge gathered from the above points is shared with relevant teams, supporting early remediation of issues.

Conclusion

During extreme stresses such as Covid-19 and the global financial crisis, banks’ internal models can fail, not because of modelling issues but due to systemic market issues. Under FRTB, the BCBS show that they recognise this and, in these rare situations, may provide exemptions. The EBA’s recently published technical standards provide better guidance on which indicators can be used to identify these periods of extreme stresses. Although they do not lay out a prescriptive and definitive set of indicators, the technical standards provide a starting point for banks to develop suitable monitoring frameworks.

For more information on this topic, contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Hardial Kalsi (Manager).

The Ridge Backtest Metric: Backtesting Expected Shortfall

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

Challenges with backtesting Expected Shortfall

Recent regulations are increasingly moving toward the use of Expected Shortfall (ES) as a measure to capture risk. Although ES fixes many issues with VaR, there are challenges when it comes to backtesting.

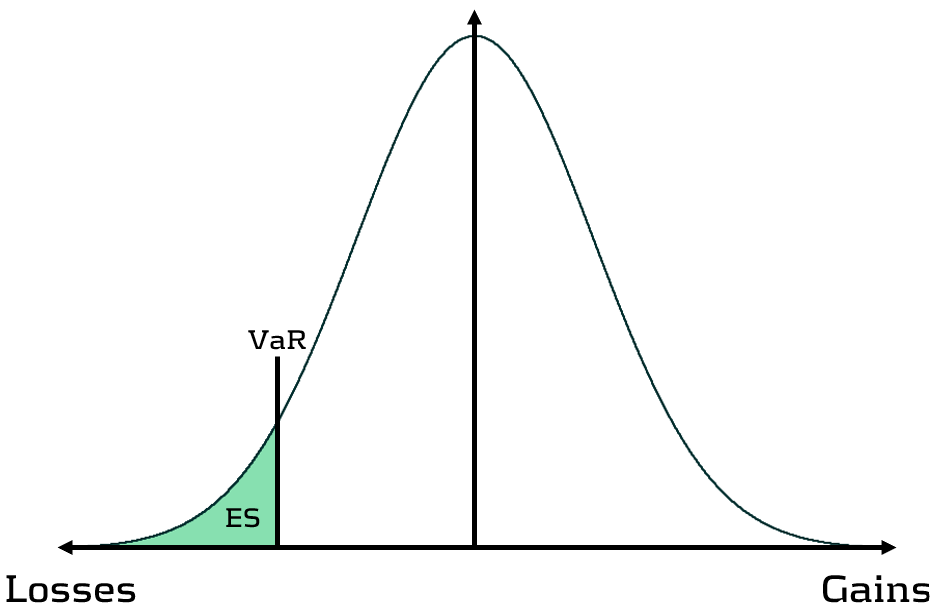

Although VaR has been widely-used for decades, its shortcomings have prompted the switch to ES. Firstly, as a percentile measure, VaR does not adequately capture tail risk. Unlike VaR, which gives the maximum expected portfolio loss in a given time period and at a specific confidence level, ES gives the average of all potential losses greater than VaR (see figure 1). Consequently, unlike Var, ES can capture a range of tail scenarios. Secondly, VaR is not sub-additive. ES, however, is sub-additive, which makes it better at accounting for diversification and performing attribution. As such, more recent regulation, such as FRTB, is replacing the use of VaR with ES as a risk measure.

Figure 1: Comparison of VaR and ES

Elicitability is a necessary mathematical condition for backtestability. As ES is non-elicitable, unlike VaR, ES backtesting methods have been a topic of debate for over a decade. Backtesting and validating ES estimates is problematic – how can a daily ES estimate, which is a function of a probability distribution, be compared with a realised loss, which is a single loss from within that distribution? Many existing attempts at backtesting have relied on approximations of ES, which inevitably introduces error into the calculations.

The three main issues with ES backtesting can be summarised as follows:

- Transparency

- Without reliable techniques for backtesting ES, banks struggle to have transparency on the performance of their models. This is particularly problematic for regulatory compliance, such as FRTB.

- Sensitivity

- Existing VaR and ES backtesting techniques are not sensitive to the magnitude of the overages. Instead, these techniques, such as the Traffic Light Test (TLT), only consider the frequency of overages that occur.

- Stability

- As ES is conditional on VaR, any errors in VaR calculation lead to errors in ES. Many existing ES backtesting methodologies are highly sensitive to errors in the underlying VaR calculations.

Ridge Backtesting: A solution to ES backtesting

One often-cited solution to the ES backtesting problem is the ridge backtesting approach. This method allows non-elicitable functions, such as ES, to be backtested in a manner that is stable with regards to errors in the underlying VaR estimations. Unlike traditional VaR backtesting methods, it is also sensitive to the magnitude of the overages and not just their frequency.

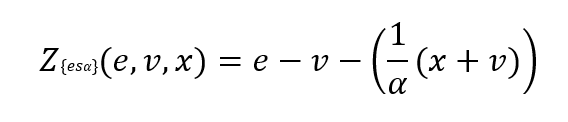

The ridge backtesting test statistic is defined as:

where 𝑣 is the VaR estimation, 𝑒 is the expected shortfall prediction, 𝑥 is the portfolio loss and 𝛼 is the confidence level for the VaR estimation.

The value of the ridge backtesting test statistic provides information on whether the model is over or underpredicting the ES. The technique also allows for two types of backtesting; absolute and relative. Absolute backtesting is denominated in monetary terms and describes the absolute error between predicted and realised ES. Relative backtesting is dimensionless and describes the relative error between predicted and realised ES. This can be particularly useful when comparing the ES of multiple portfolios. The ridge backtesting result can be mapped to the existing Basel TLT RAG zones, enabling efficient integration into existing risk frameworks.

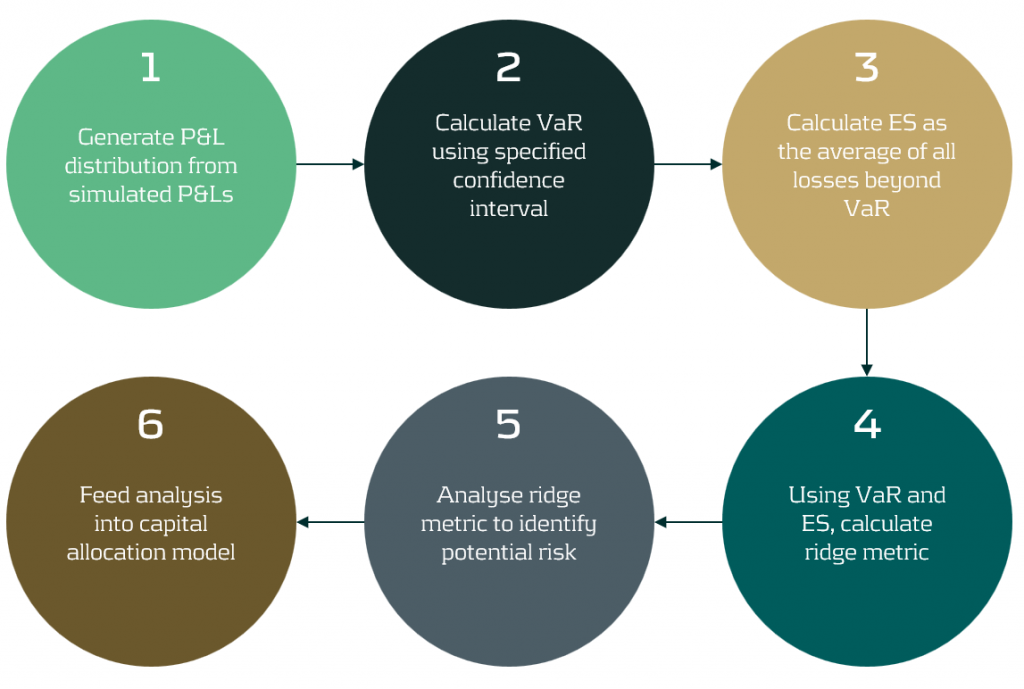

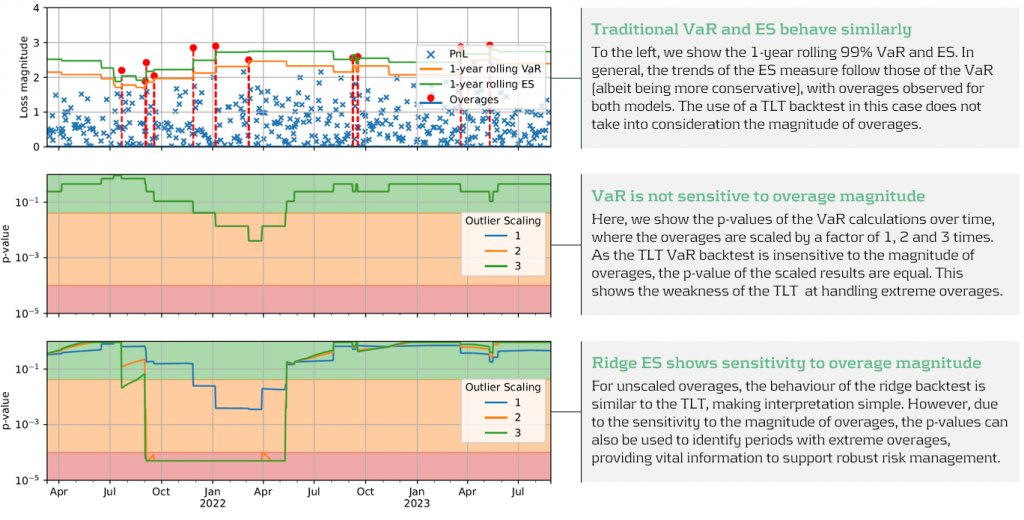

Figure 2: The ridge backtesting methodology

Sensitivity to Overage Magnitude

Unlike VaR backtesting, which does not distinguish between overages of different magnitudes, a major advantage of ES ridge backtesting is that it is sensitive to the size of each overage. This allows for better risk management as it identifies periods with large overages and also periods with high frequency of overages.

Below, in figure 3, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the ridge backtest by comparing it against a traditional VaR backtest. A scenario was constructed with P&Ls sampled from a Normal distribution, from which a 1-year 99% VaR and ES were computed. The sensitivity of ridge backtesting to overage magnitude is demonstrated by applying a range of scaling factors, increasing the size of overages by factors of 1, 2 and 3. The results show that unlike the traditional TLT, which is sensitive only to overage frequency, the ridge backtesting technique is effective at identifying both the frequency and magnitude of tail events. This enables risk managers to react more quickly to volatile markets, regime changes and mismodelling of their risk models.

Figure 3: Demonstration of ridge backtesting’s sensitivity to overage magnitude.

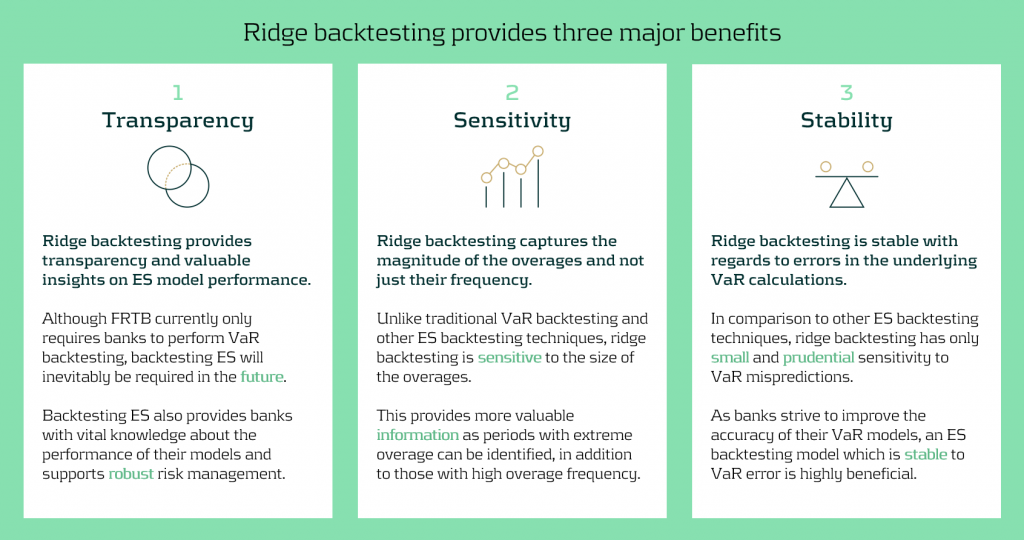

The Benefits of Ridge Backtesting

Rapidly changing regulation and market regimes require banks enhance their risk management capabilities to be more reactive and robust. In addition to being a robust method for backtesting ES, ridge backtesting provides several other benefits over alternative backtesting techniques, providing banks with metrics that are sensitive and stable.

Despite the introduction of ES as a regulatory requirement for banks choosing the internal models approach (IMA), regulators currently do not require banks to backtest their ES models. This leaves a gap in banks’ risk management frameworks, highlighting the necessity for a reliable ES backtesting technique. Despite this, banks are being driven to implement ES backtesting methodologies to be compliant with future regulation and to strengthen their risk management frameworks to develop a comprehensive understanding of their risk.

Ridge backtesting gives banks transparency to the performance of their ES models and a greater reactivity to extreme events. It provides increased sensitivity over existing backtesting methodologies, providing information on both overage frequency and magnitude. The method also exhibits stability to any underlying VaR mismodelling.

In figure 4 below, we summarise the three major benefits of ridge backtesting.

Figure 4: The three major benefits of ridge backtesting.

Conclusion

The lack of regulatory control and guidance on backtesting ES is an obvious concern for both regulators and banks. Failure to backtest their ES models means that banks are not able to accurately monitor the reliability of their ES estimates. Although the complexities of backtesting ES has been a topic of ongoing debate, we have shown in this article that ridge backtesting provides a robust and informative solution. As it is sensitive to the magnitude of overages, it provides a clear benefit in comparison to traditional VaR TLT backtests that are only sensitive to overage frequency. Although it is not a regulatory requirement, regulators are starting to discuss and recommend ES backtesting. For example, the PRA, EBA and FED have all recommended ES backtesting in some of their latest publications. However, despite the fact that regulation currently only requires banks to perform VaR backtesting, banks should strive to implement ES backtesting as it supports better risk management.

For more information on this topic, contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Hardial Kalsi (Manager).

Exploring IFRS 9 Best Practices: Insights from Leading European Banks

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

Across the whole of Europe, banks apply different techniques to model their IFRS9 Expected Credit Losses on a best estimate basis. The diverse spectrum of modelling techniques raises the question: what can we learn from each other, such that we all can improve our own IFRS 9 frameworks? For this purpose, Zanders hosted a webinar on the topic of IFRS 9 on the 29th of May 2024. This webinar was in the form of a panel discussion which was led by Martijn de Groot and tried to discuss the differences and similarities by covering four different topics. Each topic was discussed by one panelist, who were Pieter de Boer (ABN AMRO, Netherlands), Tobia Fasciati (UBS, Switzerland), Dimitar Kiryazov (Santander, UK), and Jakob Lavröd (Handelsbanken, Sweden).

The webinar showed that there are significant differences with regards to current IFRS 9 issues between European banks. An example of this is the lingering effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is more prominent in some countries than others. We also saw that each bank is working on developing adaptable and resilient models to handle extreme economic scenarios, but that it remains a work in progress. Furthermore, the panel agreed on the fact that SICR remains a difficult metric to model, and, therefore, no significant changes are to be expected on SICR models.

Covid-19 and data quality

The first topic covered the COVID-19 period and data quality. The poll question revealed widespread issues with managing shifts in their IFRS 9 model resulting from the COVID-19 developments. Pieter highlighted that many banks, especially in the Netherlands, have to deal with distorted data due to (strong) government support measures. He said this resulted in large shifts of macroeconomic variables, but no significant change in the observed default rate. This caused the historical data not to be representative for the current economic environment and thereby distorting the relationship between economic drivers and credit risk. One possible solution is to exclude the COVID-19 period, but this will result in the loss of data. However, including the COVID-19 period has a significant impact on the modelling relations. He also touched on the inclusion of dummy variables, but the exact manner on how to do so remains difficult.

Dimitar echoed these concerns, which are also present in the UK. He proposed using the COVID-19 period as an out-of-sample validation to assess model performance without government interventions. He also talked about the problems with the boundaries of IFRS 9 models. Namely, he questioned whether models remain reliable when data exceeds extreme values. Furthermore, he mentioned it also has implications for stress testing, as COVID-19 is a real life stress scenario, and we might need to think about other modelling techniques, such as regime-switching models.

Jakob found the dummy variable approach interesting and also suggested the Kalman filter or a dummy variable that can change over time. He pointed out that we need to determine whether the long term trend is disturbed or if we can converge back to this trend. He also mentioned the need for a common data pipeline, which can also be used for IRB models. Pieter and Tobia agreed, but stressed that this is difficult since IFRS 9 models include macroeconomic variables and are typically more complex than IRB.

Significant Increase in Credit Risk

The second topic covered the significant increase in credit risk (SICR). Jakob discussed the complexity of assessing SICR and the lack of comprehensive guidance. He stressed the importance of looking at the origination, which could give an indication on the additional risk that can be sustained before deeming a SICR.

Tobia pointed out that it is very difficult to calibrate, and almost impossible to backtest SICR. Dimitar also touched on the subject and mentioned that the SICR remains an accounting concept that has significant implications for the P&L. The UK has very little regulations on this subject, and only requires banks to have sufficient staging criteria. Because of these reasons, he mentioned that he does not see the industry converging anytime soon. He said it is going to take regulators to incentivize banks to do so. Dimitar, Jakob, and Tobia also touched upon collective SICR, but all agreed this is difficult to do in practice.

Post Model Adjustments

The third topic covered post model adjustments (PMAs). The results from the poll question implied that most banks still have PMAs in place for their IFRS 9 provisions. Dimitar responded that the level of PMAs has mostly reverted back to the long term equilibrium in the UK. He stated that regulators are forcing banks to reevaluate PMAs by requiring them to identify the root cause. Next to this, banks are also required to have a strategy in place when these PMAs are reevaluated or retired, and how they should be integrated in the model risk management cycle. Dimitar further argued that before COVID-19, PMAs were solely used to account for idiosyncratic risk, but they stayed around for longer than anticipated. They were also used as a countercyclicality, which is unexpected since IFRS 9 estimations are considered to be procyclical. In the UK, banks are now building PMA frameworks which most likely will evolve over the coming years.

Jakob stressed that we should work with PMAs on a parameter level rather than on ECL level to ensure more precise adjustments. He also mentioned that it is important to look at what comes before the modelling, so the weights of the scenarios. At Handelsbanken, they first look at smaller portfolios with smaller modelling efforts. For the larger portfolios, PMAs tend to play less of a role. Pieter added that PMAs can be used to account for emerging risks, such as climate and environmental risks, that are not yet present in the data. He also stressed that it is difficult to find a balance between auditors, who prefer best estimate provisions, and the regulator, who prefers higher provisions.

Linking IFRS 9 with Stress Testing Models

The final topic links IFRS 9 and stress testing. The poll revealed that most participants use the same models for both. Tobia discussed that at UBS the IFRS 9 model was incorporated into their stress testing framework early on. He pointed out the flexibility when integrating forecasts of ECL in stress testing. Furthermore, he stated that IFRS 9 models could cope with stress given that the main challenge lies in the scenario definition. This is in contrast with others that have been arguing that IFRS 9 models potentially do not work well under stress. Tobia also mentioned that IFRS 9 stress testing and traditional stress testing need to have aligned assumptions before integrating both models in each other.

Jakob agreed and talked about the perfect foresight assumption, which suggests that there is no need for additional scenarios and just puts a weight of 100% on the stressed scenario. He also added that IFRS 9 requires a non-zero ECL, but a highly collateralized portfolio could result in zero ECL. Stress testing can help to obtain a loss somewhere in the portfolio, and gives valuable insights on identifying when you would take a loss.

Pieter pointed out that IFRS 9 models differ in the number of macroeconomic variables typically used. When you are stress testing variables that are not present in your IFRS 9 model, this could become very complicated. He stressed that the purpose of both models is different, and therefore integrating both can be challenging. Dimitar said that the range of macroeconomic scenarios considered for IFRS 9 is not so far off from regulatory mandated stress scenarios in terms of severity. However, he agreed with Pieter that there are different types of recessions that you can choose to simulate through your IFRS 9 scenarios versus what a regulator has identified as systemic risk for an industry. He said you need to consider whether you are comfortable relying on your impairment models for that specific scenario.

This topic concluded the webinar on differences and similarities across European countries regarding IFRS 9. We would like to thank the panelists for the interesting discussion and insights, and the more than 100 participants for joining this webinar.

Interested to learn more? Contact Kasper Wijshoff, Michiel Harmsen or Polly Wong for questions on IFRS 9.

Unlocking the Hidden Gems of the SAP Credit Risk Analyzer

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

While many business and SAP users are familiar with its core functionalities, such as limit management applying different limit types and the core functionality of attributable amount determination, several less known SAP standard features can enhance your credit risk management processes.

In this article, we will explore these hidden gems, such as Group Business Partners and the ways to manage the limit utilizations using manual reservations and collateral.

Group Business Partner Use

One of the powerful yet often overlooked features of the SAP Credit Risk Analyzer is the ability to use Group Business Partners (BP). This functionality allows you to manage credit and settlement risk at a bank group level rather than at an individual transactional BP level. By consolidating credit and settlement exposure for related entities under a single group business partner, you can gain a holistic view of the risks associated with an entire banking group. This is particularly beneficial for organizations dealing with banking corporations globally and allocating a certain amount of credit/settlement exposure to banking groups. It is important to note that credit ratings are often reflected at the group bank level. Therefore, the use of Group BPs can be extended even further with the inclusion of credit ratings, such as S&P, Fitch, etc.

Configuration: Define the business partner relationship by selecting the proper relationship category (e.g., Subsidiary of) and setting the Attribute Direction to "Also count transactions from Partner 1 towards Partner 2," where Partner 2 is the group BP.

Master Data: Group BPs can be defined in the SAP Business Partner master data (t-code BP). Ensure that all related local transactional BPs are added in the relationship to the appropriate group business partner. Make sure the validity period of the BP relationship is valid. Risk limits are created using the group BP instead of the transactional BP.

Reporting: Limit utilization (t-code TBLB) is consolidated at the group BP level. Detailed utilization lines show the transactional BP, which can be used to build multiple report variants to break down the limit utilization by transactional BP (per country, region, etc.).

Having explored the benefits of using Group Business Partners, another feature that offers significant flexibility in managing credit risk is the use of manual reservations and collateral contracts.

Use of Manual Reservations

Manual reservations in the SAP Credit Risk Analyzer provide an additional layer of flexibility in managing limit utilization. This feature allows risk managers to manually add a portion of the credit/settlement utilization for specific purposes or transactions, ensuring that critical operations are not hindered by unexpected credit or settlement exposure. It is often used as a workaround for issues such as market data problems, when SAP is not able to calculate the NPV, or for complex financial instruments not yet supported in the Treasury Risk Management (TRM) or Credit Risk Analyzer (CRA) settings.

Configuration: Apart from basic settings in the limit management, no extra settings are required in SAP standard, making the use of reservations simpler.

Master data: Use transaction codes such as TLR1 to TLR3 to create, change, and display the reservations, and TLR4 to collectively process them. Define the reservation amount, specify the validity period, and assign it to the relevant business partner, transaction, limit product group, portfolio, etc. Prior to saving the reservation, check in which limits your reservation will be reflected to avoid having any idle or misused reservations in SAP.

While manual reservations provide a significant boost to flexibility in limit management, another critical aspect of credit risk management is the handling of collateral.

Collateral

Collateral agreements are a fundamental aspect of credit risk management, providing security against potential defaults. The SAP Credit Risk Analyzer offers functionality for managing collateral agreements, enabling corporates to track and value collateral effectively. This ensures that the collateral provided is sufficient to cover the exposure, thus reducing the risk of loss.

SAP TRM supports two levels of collateral agreements:

- Single-transaction-related collateral

- Collateral agreements.

Both levels are used to reduce the risk at the level of attributable amounts, thereby reducing the utilization of limits.

Single-transaction-related collateral: SAP distinguishes three types of collateral value categories:

- Percentual collateralization

- Collateralization using a collateral amount

- Collateralization using securities

Configuration: configure collateral types and collateral priorities, define collateral valuation rules, and set up the netting group.

Master Data: Use t-code KLSI01_CFM to create collateral provisions at the appropriate level and value. Then, this provision ID can be added to the financial object.

Reporting: both manual reservations and collateral agreements are visible in the limit utilization report as stand- alone utilization items.

By leveraging these advanced features, businesses can significantly enhance their risk management processes.

Conclusion

The SAP Credit Risk Analyzer is a comprehensive tool that offers much more than meets the eye. By leveraging its hidden functionalities, such as Group Business Partner use, manual reservations, and collateral agreements, businesses can significantly enhance their credit risk management processes. These features not only provide greater flexibility and control but also ensure a more holistic and robust approach to managing credit risk. As organizations continue to navigate the complexities of the financial landscape, unlocking the full potential of the SAP Credit Risk Analyzer can be a game-changer in achieving effective risk management.

If you have questions or are keen to see the functionality in our Zanders SAP Demo system, please feel free to contact Aleksei Abakumov or any Zanders SAP consultant.

Default modelling in an age of agility

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

In brief:

- Prevailing uncertainty in geopolitical, economic and regulatory environments demands a more dynamic approach to default modelling.

- Traditional methods such as logistic regression fail to address the non-linear characteristics of credit risk.

- Score-based models can be cumbersome to calibrate with expertise and can lack the insight of human wisdom.

- Machine learning lacks the interpretability expected in a world where transparency is paramount.

- Using the Bayesian Gaussian Process Classifier defines lending parameters in a more holistic way, sharpening a bank’s ability to approve creditworthy borrowers and reject proposals from counterparties that are at a high risk of default.

Historically high levels of economic volatility, persistent geopolitical unrest, a fast-evolving regulatory environment – a perpetual stream of disruption is highlighting the limitations and vulnerabilities in many credit risk approaches. In an era where uncertainty persists, predicting risk of default is becoming increasingly complex, and banks are increasingly seeking a modelling approach that incorporates more flexibility, interpretability, and efficiency.

While logistic regression remains the market standard, the evolution of the digital treasury is arming risk managers with a more varied toolkit of methodologies, including those powered by machine learning. This article focuses on the Bayesian Gaussian Process Classifier (GPC) and the merits it offers compared to machine learning, score-based models, and logistic regression.

A non-parametric alternative to logistic regression

The days of approaching credit risk in a linear, one-dimensional fashion are numbered. In today’s fast paced and uncertain world, to remain resilient to rising credit risk, banks have no choice other than to consider all directions at once. With the GPC approach, the linear combination of explanatory variables is replaced by a function, which is iteratively updated by applying Bayes’ rule (see Bayesian Classification With Gaussian Processes for further detail).

For default modelling, a multivariate Gaussian distribution is used, hence forsaking linearity. This allows the GPC to parallel machine learning (ML) methodologies, specifically in terms of flexibility to incorporate a variety of data types and variables and capability to capture complex patterns hidden within financial datasets.

A model enriched by expert wisdom

Another way GPC shows similar characteristics to machine learning is in how it loosens the rigid assumptions that are characteristic of many traditional approaches, including logistic regression and score-based models. To explain, one example is the score-based Corporate Rating Model (CRM) developed by Zanders. This is the go-to model of Zanders to assess the creditworthiness of corporate counterparties. However, calibrating this model and embedding the opinion of Zanders’ corporate rating experts is a time-consuming task. The GPC approach streamlines this process significantly, delivering both greater cost- and time-efficiencies. The incorporation of prior beliefs via Bayesian inference permits the integration of expert knowledge into the model, allowing it to reflect predetermined views on the importance of certain variables. As a result, the efficiency gains achieved through the GPC approach don’t come at the cost of expert wisdom.

Enabling explainable lending decisions

As well as our go-to CRM, Zanders also houses machine learning approaches to default modelling. Although this generates successful outcomes, with machine learning, the rationale behind a credit decision is not explicitly explained. In today’s volatile environment, an unexplainable solution can fall short of stakeholder and regulator expectations – they increasingly want to understand the reasoning behind lending decisions at a forensic level.

Unlike the often ‘black-box’ nature of ML models, with GPC, the path to a decision or solution is both transparent and explainable. Firstly, the GPC model’s hyperparameters provide insights into the relevance and interplay of explanatory variables with the predicted outcome. In addition, the Bayesian framework sheds light on the uncertainty surrounding each hyperparameter. This offers a posterior distribution that quantifies confidence in these parameter estimates. This aspect adds substantial risk assessment value, contrary to the typical point estimate outputs from score-based models or deterministic ML predictions. In short, an essential advantage of the GPC over other approaches is its ability to generate outcomes that withstand the scrutiny of stakeholders and regulators.

A more holistic approach to probability of default modelling

In summary, if risk managers are to tackle the mounting complexity of evaluating probability of default, they need to approach it non-linearly and in a way that’s explainable at every level of the process. This is throwing the spotlight onto more holistic approaches, such as the Gaussian Process Classifier. Using this methodology allows for the incorporation of expert intuition as an additional layer to empirical evidence. It is transparent and accelerates calibration without forsaking performance. This presents an approach that not only incorporates the full complexity of credit risk but also adheres to the demands for model interpretability within the financial sector.

Are you interested in how you could use GPC to enhance your approach to default modelling? Contact Kyle Gartner for more information.

Surviving Prepayments: A Comparative Look at Prepayment Modelling Techniques

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

In brief

- Prepayment modelling can help institutions successfully prepare for and navigate a rise in prepayments due to changes in the financial landscape.

- Two important prepayment modelling types are highlighted and compared: logistic regression vs Cox Proportional Hazard.

- Although the Cox Proportional Hazard model is theoretically preferred under specific conditions, the logical regression is preferred in practice under many scenarios.

The borrowers' option to prepay on their loan induces uncertainty for lenders. How can lenders protect themselves against this uncertainty? Various prepayment modelling approaches can be selected, with option risk and survival analyses being the main alternatives under discussion.

Prepayment options in financial products spell danger for institutions. They inject uncertainty into mortgage portfolios and threaten fixed-rate products with volatile cashflows. To safeguard against losses and stabilize income, institutions must master precise prepayment modelling.

This article delves into the nuances and options regarding the modelling of mortgage prepayments (a cornerstone of Asset Liability Management (ALM)) with a specific focus on survival models.

Understanding the influences on prepayment dynamics

Prepayments are triggered by a range of factors – everything from refinancing opportunities to life changes, such as selling a house due to divorce or moving. These motivations can be grouped into three overarching categories: refinancing factors, macroeconomic factors, and loan-specific factors.

- Refinancing factors

This encompasses key financial drivers (such as interest rates, mortgage rates and penalties) and loan-specific information (including interest rate reset dates and the interest rate differential for the customer). Additionally, the historical momentum of rates and the steepness of the yield curve play crucial roles in shaping refinancing motivations. - Macro-economic factors

The overall state of the economy and the conditions of the housing market are pivotal forces on a borrower's inclination to exercise prepayment options. Furthermore, seasonality adds another layer of variability, with prepayments being notably higher in certain months. For example, in December, when clients have additional funds due to payment of year-end bonusses and holiday budgets. - Loan-specific factors

The age of the mortgage, type of mortgage, and the nature of the property all contribute to prepayment behavior. The seasoning effect, where the probability of prepayment increases with the age of the mortgage, stands out as a paramount factor.

These factors intricately weave together, shaping the landscape in which customers make decisions regarding prepayments. Prepayment modelling plays a vital role in helping institutions to predict the impact of these factors on prepayment behavior.

The evolution of prepayment modelling

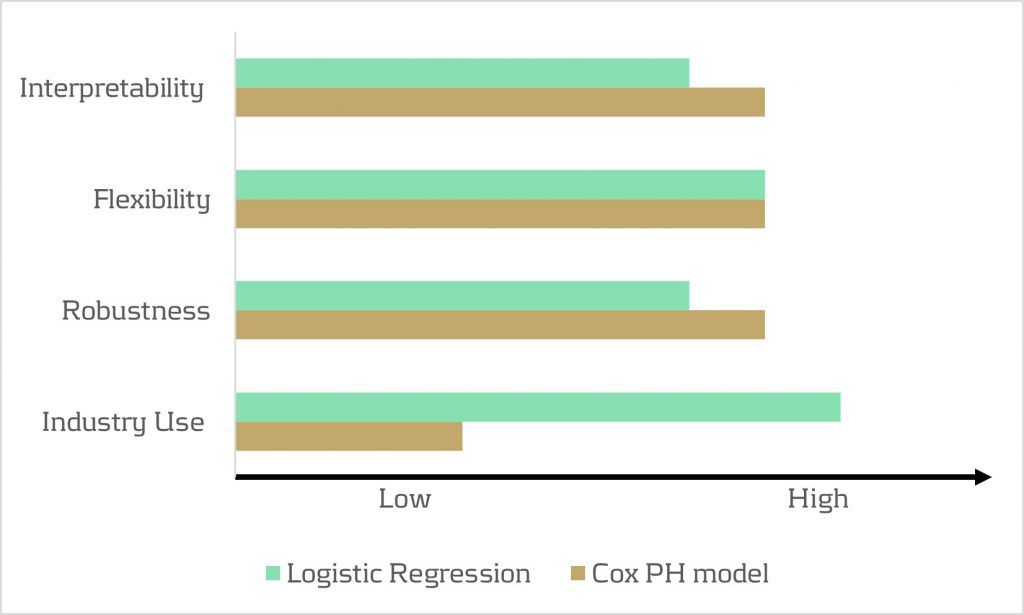

Research on prepayment modelling originated in the 1980s and initially centered around option-theoretic models that assume rational customer behavior. Over time, empirical models that cater for customer irrationality have emerged and gained prominence. These models aim to capture the more nuanced behavior of customers by explaining the relationship between prepayment rates and various other factors. In this article, we highlight two important types of prepayment models: logistic regression and Cox Proportional Hazard (Survival Model).

Logistic regression

Logistic regression, specifically its logit or probit variant, is widely employed in prepayment analysis. This is largely because it caters for the binary nature of the dependent variable indicating the occurrence of prepayment events and it moreover flexible. That is, the model can incorporate mortgage-specific and overall economic factors as regressors and can handle time-varying factors and a mix of continuous and categorical variables.

Once the logistic regression model is fitted to historical data, its application involves inputting the characteristics of a new mortgage and relevant economic factors. The model’s output provides the probability of the mortgage undergoing prepayment. This approach is already prevalent in banking practices, and frequently employed in areas such as default modeling and credit scoring. Consequently, it’s favored by many practitioners for prepayment modeling.

Despite its widespread use, the model has drawbacks. While its familiarity in banking scenarios offers simplicity in implementation, it lacks the interpretability characteristic of the Proportional Hazard model discussed below. Furthermore, in terms of robustness, a minimal drawback is that any month-on-month change in results can be caused by numerous factors, which all affect each other.

Cox Proportional Hazard (Survival model)

The Cox Proportional Hazard (PH) model, developed by Sir David Cox in 1972, is one of the most popular models in survival analysis. It consists of two core parts:

- Survival time. With the Cox PH model, the variable of interest is the time to event. As the model stems from medical sciences, this event is typically defined as death. The time variable is referred to as survival time because it’s the time a subject has survived over some follow-up period.

- Hazard rate. This is the distribution of the survival time and is used to predict the probability of the event occurring in the next small-time interval, given that the event has not occurred beforehand. This hazard rate is modelled based on the baseline hazard (the time development of the hazard rate of an average patient) and a multiplier (the effect of patient-specific variables, such as age and gender). An important property of the model is that the baseline hazard is an unspecified function.

To explain how this works in the context of prepayment modelling for mortgages:

- The event of interest is the prepayment of a mortgage.

- The hazard rate is the probability of a prepayment occurring in the next month, given that the mortgage has not been prepaid beforehand. Since the model estimates hazard rates of individual mortgages, it’s modelled using loan-level data.

- The baseline hazard is the typical prepayment behavior of a mortgage over time and captures the seasoning effect of the mortgage.

- The multiplier of the hazard rate is based on mortgage-specific variables, such as the interest rate differential and seasonality.

For full prepayments, where the mortgage is terminated after the event, the Cox PH model applies in its primary format. However, partial prepayments (where the event is recurring) require an extended version, known as the recurrent event PH model. As a result, when using the Cox PH model, , the modelling of partial and full prepayments should be conducted separately, using slightly different models.

The attractiveness of the Cox PH model is due to several features:

- The interpretability of the model. The model makes it possible to quantify the influence of various factors on the likelihood of prepayment in an intuitive way.

- The flexibility of the model. The model offers the flexibility to handle time-varying factors and a mix of continuous and categorical variables, as well as the ability to incorporate recurrent events.

- The multiplier means the hazard rate can’t be negative. The exponential nature of mortgage-specific variables ensures non-negative estimated hazard rates.

Despite the advantages listed above presenting a compelling theoretical case for using the Cox PH model, it faces limited adoption in practical prepayment modelling by banks. This is primarily due to its perceived complexity and unfamiliarity. In addition, when loan-level data is unavailable, the Cox PH model is no longer an option for prepayment modeling.

Logistic regression vs Cox Proportional Hazard

In scenarios with individual survival time data and censored observations, the Cox PH model is theoretically preferred over logistic regression. This preference arises because the Cox PH model leverages this additional information, whereas logistic regression focuses solely on binary outcomes, disregarding survival time and censoring.

However, practical considerations also come into play. Research shows that in certain cases, the logistic regression model closely approximates the results of the Cox PH model, particularly when hazard rates are low. Given that prepayments in the Netherlands are around 3-10% and associated hazard rates tend to be low, the performance gap between logistic regression and the Cox PH model is minimal in practice for this application. Also, the necessity to create a different PH model for full and partial prepayment adds an additional burden on ALM teams.

In conclusion, when faced with the absence of loan-level data, the logistic regression model emerges as a pragmatic choice for prepayment modeling. Despite the theoretical preference for the Cox PH model under specific conditions, the real-world performance similarities, coupled with the familiarity and simplicity of logistic regression, provide a practical advantage in many scenarios.

How can Zanders support?

Zanders is a thought leader on IRRBB-related topics. We enable banks to achieve both regulatory compliance and strategic risk goals by offering support from strategy to implementation. This includes risk identification, formulating a risk strategy, setting up an IRRBB governance and framework, and policy or risk appetite statements. Moreover, we have an extensive track record in IRRBB and behavioral models such as prepayment models, hedging strategies, and calculating risk metrics, both from model development and model validation perspectives.

Are you interested in IRRBB-related topics such as prepayments? Contact Jaap Karelse, Erik Vijlbrief, Petra van Meel (Netherlands, Belgium and Nordic countries) or Martijn Wycisk (DACH region) for more information.

Zanders supercharges the growth of its US risk advisory practice with the appointment of managing director, Dan Delean

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

Dan Delean recently joined Zanders as Managing Director of our newly formed US risk advisory practice. With a treasury career spanning more than 30 years, including 15 years specializing in risk advisory, he comes to us with an impressive track record of building high performing Big 4 practices. As Dan will be spearheading the growth of Zanders’ risk advisory capabilities in the US, we asked him to share his vision for our future in the region.

Q. What excites you the most about leading Zanders' entry into the US market for risk advisory services?

Dan: This is a chance to build a world-class risk advisory practice in the US. Under the leadership of Paul DeCrane, the quality of Zanders reputation in the US has already been firmly established and I’m excited to build on this. I love to build – teams, solutions, physical building – and I am unnaturally passionate about treasury. Treasury is a small universe here, so getting traction is a key challenge – but once we do, it will catch fire.

Q. What do you see as the unique challenges (or opportunities) for Zanders in the US market?

Dan: A key concern for financial institutions in the US right now is the low availability of highly competent treasury professionals. Rising interest rates, combined with economic and political uncertainty, are driving up demand for deeper treasury insights in the US. In particular, the regulatory regime here is increasing its focus on liquidity and funding challenges, with a number of banking organizations on the ‘list’ for closing. But while the need for deep treasury competencies is growing fast, the pool of talent can’t keep up with this demand. This is an expertise gap Zanders is perfectly placed to address.

Q. How do you plan to tailor Zanders' risk advisory services to meet the specific needs and expectations of US clients?

Dan: My plan is to attract the best talent available, building a team with the capability to work with clients to tackle the hardest problems in the market. I want to build a recognized risk advisory team, that’s trusted by clients with difficult challenges. My intention is to focus on building these competencies through a highly focused approach to teaming.

Q. In what ways do you believe Zanders' approach to risk advisory services sets it apart from other firms in the US market?

Dan: Focus on competencies and effective teaming will make Zanders stand out among advisory businesses in the US. Zanders is an expert-driven, competency focused practice, with a large team of seasoned treasury and risk professionals and a willingness to team up with other industry players. This approach is not common in the US. Most firms here deploy leverage models or are highly technical.

Q. What kind of culture or working environment do you aim to foster within the US branch of Zanders?

Dan: I’m committed to recruiting well, training even better, and being a key supporter of my team. I believe culture starts at the top, so all team members that join or work with us need to buy into the expert model and Zanders’ approach to advisory. Within this culture, trust and accountability will always be core tenets – these will be central to my approach to teaming.

With his value-driven, competency-led approach to teaming and practice development, there’s no-one better qualified than Dan to lead the growth of our US risk advisory. To learn more about Zanders and what makes us different, please visit our About Zanders page.

European committee accepts NII SOT while EBA published its roadmap for IRRBB

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

The European Committee (EC) has approved the regulatory technical standards (RTS) that include the specification of the Net Interest Income (NII) Supervisory Outlier Test (SOT). The SOT limit for the decrease in NII is set at 5% of Tier 1 capital. Since the three-month scrutiny period has ended it is expected that the final RTS will be published soon. 20 days after the publication the RTS will go into force. The acceptance of the NII SOT took longer than expected among others due to heavy pushback from the banking sector. The SOT, and the fact that some banks rely heavily on it for their internal limit framework is also one of the key topics on the heatmap IRRBB published by the European Banking Authority (EBA). The heatmap detailing its scrutiny plans for implementing interest rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB) standards across the EU. In the short to medium term (2024/Mid-2025), the focus is on

- The EBA has noted that some banks use the as an internal limit without identifying other internal limits. The EBA will explore the development of complementary indicators useful for SREP purposes and supervisory stress testing.

- The different practices on behavioral modelling of NMDs reported by the institutions.

- The variety of hedging strategies that institutions have implemented.

- Contribute to the Dynamic Risk Management project of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), which will replace the macro hedge accounting standard.

In the medium to long-term objectives (beyond mid-2025) the EBA mentions it will monitor the five-year cap on NMDs and CSRBB definition used by banks. No mention is made by the EBA on the consultation started by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, on the newly calibrated interest rate scenarios methodology and levels. In the coming weeks, Zanders will publish a series of articles on the Dynamic Risk Management project of the IASB and what implications it will have for banks. Please contact us if you have any questions on this topic or others such as NMD modelling or the internal limit framework/ risk appetite statements.