This article explores how newly established treasury functions can lay foundations and go beyond day 1 readiness to establish effective, scalable, and resilient cash and liquidity management for the group, representing a critical lever for long-term financial stability and value creation of the business.

Introduction

In the previous article, From Day 1 to Strategic Partner: Building a Treasury Function for a Carved-Out Business, we highlighted the importance of a tailored target operating model (TOM) to establish a solid strategic and organizational base for the new treasury. Following the definition of the treasury TOM and once day 1 readiness measures are in place, the next priority is to focus on value creation via cash and liquidity management, which represent another key pillar for a successful treasury implementation and treasury process. Cash and liquidity capabilities play a vital role in ensuring treasury delivers both operational continuity and strategic value. This article outlines how to build that foundation by establishing robust and forward-looking cash and liquidity management processes already at the time of the transaction, addressing immediate post-transaction needs, and enabling mid-term process efficiency.

Prepare for Day 1: Managing Liquidity Readiness

When preparing for the closing of an M&A transaction, treasury plays a critical role in ensuring that the new organization operates independently from Day 1. Liquidity planning is essential as cash pressures often peak around the time of legal close.

The following aspects may erase cash reserves if not properly anticipated:

- Upfront costs (transaction fees, legal, advisory, integration).

- Debt financing frameworks still under negotiation.

- Cash repatriation constraints or internal investment requirements to support the separation.

Hence, treasury must address these topics in cash and liquidity planning by:

- Modeling short-term needs under multiple scenarios based on validated assumptions on the business’ structure and liquidity needs.

- Ensuring cash visibility and centralization of cash, where possible to manage funding efficiently.

- Evaluating working capital buffers and the need for interim funding lines.

By addressing these topics before closing, the new entity enters day 1 with visibility on liquidity positions, funding plans, and confidence in its ability to operate independently.

Manage Day 1: Establishing Control, Visibility and Centralization

For a newly independent entity, cash visibility is often fragmented across systems and bank accounts, especially in the early stages after a carve-out. Yet gaining (real-time) transparency is fundamental to effective cash management and decision-making. The foundational elements to achieve at this stage are:

- Set up efficient connectivity with all banking partners.

- Deploy treasury technology (e.g., a TMS or interim solution) to aggregate bank balances and transactions centrally.

- Implement daily cash positioning processes across all relevant bank accounts.

- Define responsibilities and control mechanisms for cash operations, ensuring a clear RACI model.

Cash visibility improves control and reduces risk while enabling better liquidity allocation across the group via a centralized cash management process. The deployment of cash concentration structures, such as cash pooling, allows the unlocking of financial resources and benefits, such as fee reduction or interest optimization. Furthermore, centralized cash management data is a prerequisite for AI-driven cash applications and greater financial risk exposure definition1, which can significantly reduce manual effort in distributing and managing cash across the group.

Early Stabilization: Forecasting and Short-Term Control

Once operational continuity is secured, the focus should move to stabilizing cash and liquidity processes.

Forecasting in a post-carve-out environment is challenging, yet essential. Missing historical data, unclear transaction volumes, and transitional arrangements (e.g., TSAs) often reduce forecast accuracy.

A suitable solution is the deployment of a layered forecasting approach, including:

- Short-term cash flow forecasts (typically 13-week rolling) to guide immediate liquidity needs.

- Medium-term liquidity planning, integrated with business planning (FP&A) and CAPEX cycles.

- Stress-testing and scenario analysis to evaluate performance under simulated business conditions.

In our experience, cash forecasting is an evolving process, which can be optimized and automated over-time through data integration (e.g. from ERP system) and predictive modeling. With data quality as the foundation, cash flow forecasting can begin by establishing the most accurate starting point and committed forecasts under company control, such as opening balances and invoice payables. Once the high-certainty inputs are captured, additional cash flows such as committed accounts receivable and other material forecasts e.g. sales forecast or CAPEX forecast can be integrated.

Carved-out entities must consider the growing maturity and quality of their systems and respective data over the first 12 months after day 1.

Designing a Fit-for-Purpose Liquidity Structure

Once visibility and forecasting are addressed, the focus should immediately shift to structuring liquidity flows across the new organization. The objective is to ensure funding efficiency, mitigate cash drag and trapped cash, and enable flexibility, all within the constraints of the newly formed legal and operational setup.

Key design considerations include:

- Tailored cash pooling and automated cash concentration structures.

- Intercompany funding structures, including currency and transfer pricing alignment and documentation.

- Liquidity buffers tailored to business volatility and seasonality.

- Working capital optimization levers (e.g., payment terms, supplier financing).

Hybrid liquidity management structures, combining centralized oversight with localized autonomy for operational banking, often achieve the best balance. Zanders supports clients based on its wide experience in bank relationship strategy and liquidity optimization for disentanglements.

Optimizing Cash Flow Management towards long-term state

Throughout the transition and towards the steady-state operations, treasury must monitor and manage cash & liquidity against an evolving backdrop of business integration activities and one-off events.

These may include:

- Working capital shifts based on new supply chains or changes in customer behaviour.

- Integration costs linked to systems, people, and process harmonization.

- Divestitures or asset sales to fund operations or sharpen the business focus.

- Cash flow issues caused by system delays or supplier renegotiations.

To address this, Treasury should establish daily cash positioning routines utilizing state-of-the-art technologies and tools, escalation mechanisms, and strong collaboration with FP&A, procurement, and tax. Treasury shall also foster a “Cash First” mindset in the newly created organization. This ensures quick resolution of bottlenecks and reinforce cash flow discipline.

Strategic Liquidity Considerations for Long-Term Success

Cash and liquidity decisions taken during a carve-out will influence the new company’s financial flexibility as it takes quite some time and effort to implement changes in liquidity structures considerably at a later stage. Therefore, treasury should consider as early as possible the following aspects:

- Debt and credit rating impacts, especially if carve-out funding involves leverage.

- Treasury risk centralization (especially FX risk), to reduce cross-border inefficiencies and improve hedging performance.

- Tax and regulatory considerations, such as repatriation limitations, transfer pricing, and cash tax leakage.

- Strategic investment readiness, ensuring adequate liquidity for future M&A, CAPEX, or digital transformation.

The liquidity setup must be scalable, allowing the business to respond confidently to rapid growth, market volatility, or external shocks with resilient measures.

Zanders’ clearly sees a need for treasury functions to evolve into applying strategic enterprise liquidity models providing an efficient framework to link various stakeholders around the office of the CFO, including treasury, FP&A, risk management, accounting and more. A group-wide approach ensures alignment, cooperation and can lead to faster and more informed decision-making processes.

A Roadmap to Liquidity Maturity

The path to liquidity excellence starts with day 1 readiness preparation and implementation but extends far beyond. Treasury should approach this evolution through a structured roadmap that includes:

- Standardization of forecasting processes and technology tools.

- Centralization of liquidity governance, structures, and banking relationships.

- Continuous optimization of working capital, pooling structures, and investment of surplus funds.

- Measurement and benchmarking of liquidity KPIs and stress performance.

We bring a proven methodology and deep experience in day 1 planning and execution, as well as in post-M&A treasury transformation. We help clients design and implement cash and liquidity frameworks that deliver control, flexibility, and strategic value.

In the next edition of this series, we look at implementing effective banking strategy and funding practices within the newly carved-out entity, including key areas of focus and potential challenges.

Citations

- To learn more about this topic, read the whitepaper: Brace for AI-mpact: The six trends driving treasuries forward in 2025 - Zanders ↩︎

Ready to implement cash and liquidity management?

Contact us

In 2020, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) experienced a significant negative FX impact, putting their ability to transfer funding to their field operations at risk. This experience prompted the humanitarian organization to request the assistance of Zanders to review and enhance their FX risk management process to safeguard their vital work from future currency fluctuations.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)/Doctors Without Borders is an international humanitarian organization, best known for their medical assistance in conflict zones and in countries affected by endemic diseases. MSF manages operations in more than 70 countries, providing medical support in the afore-mentioned areas. As a non-profit organization, MSF receives funding from individual donors and private institutions from all around the world. This global footprint generates significant cash flows and financial transactions in multiple currencies, resulting in high foreign exchange (FX) exposures. Previously, these were not adequately managed through a structured FX risk management process.

Three key problem areas

The decentralized and informal nature of MSF’s FX risk management process increased their exposure to currency uncertainty, with both inflows and outflows lacking an aligned approach. Zanders highlighted the following three problem areas:

- No centralized FX hedging strategy. Incoming flows, such as funds and grants, received globally by MSF entities with fund-raising activities (“funding entities”) were directed to one of the five Operational Centers headquartered in Europe to fund field operations. Funds were transferred in their received currency which often differed from the functional currency of the Operational Centers (EUR). The Operational Centers then bore high FX exposures on the received funds as there was no FX hedging strategy in place. The market fluctuations of unhedged currencies resulted in deviations from MSF’s annual target budget.

- Funding of field operations with limited FX risk management. From the Operational Centers, quick transfer of funds to the relevant field operations was prioritized, often without considering FX implications. This posed challenges to the Operational Centers when applying FX risk management techniques as date and amount of outgoing funds was not always known.

- Insufficient provisions for funding unpredictability. Managing the FX exposure at the Operational Center level was challenging due to uncertainties in the timing and size of grants, variation in income due to inconsistent global performance, lack of internal communication on currency needs, seasonal income peaks and unpredictable funding requirements from their field operations.

A two-step solution

Through discussions, it became clear that MSF’s priority when it came to FX risk management was to safeguard the income from grants and the distribution to field operations, by protecting their annual budget rate. We applied two-steps from our Zanders’ Financial Risk Management Framework to deliver this objective.

- Step one: Identification and Measurement

In the first step, our objective was to identify the FX exposures to determine the correct approach to manage the FX risks. This led to a high-level quantification of the FX risk for each of the five Operational Centers.

To manage this risk, we advised MSF to establish an FX risk management function to manage the FX risk in a coordinated and centralized manner. This allowed for the creation of an FX hedging program consisting of a 12-month rolling forecast of inflows and outflows. This enabled MSF to hedge their net exposures for the next budget year. If the forecast had a high level of accuracy, MSF could hedge a high ratio of this forecast.

By centralizing the FX exposure, net amounts could be hedged centrally to protect the organization from large FX volatility. The hedging contracts would then determine the annual budget rate for that year, and thereby achieving the objective of protecting the annual budget rate.

- Step two: Strategy & Policy

Here, we designed a future FX risk management process and guidelines, incorporating best market practices. We developed an ‘in-common platform’ concept, enabling MSF to centralize and standardize their FX risk management process. This was formalized in an FX risk management policy.

A structured approach to FX risk management

The introduction of an FX hedging program has given the MSF team more clarity on their FX risk exposure. This enables them to manage fluctuations in currency more proactively and pragmatically to minimize the impact on their budgets and optimize funding for their field operations.

“The result is extremely positive,” says MSF’s Treasury Lead. “We used the FX hedging program to determine the annual budget rate for next year. With this, we are very close to our budget, and we have managed to protect at least 80% of the funds and grants for the budget.” Furthermore, the FX hedging program inspired MSF entities to tackle other treasury challenges collectively as opposed to addressing them individually.

However, there are still further improvements ahead. “There are challenges we still face around the accuracy of the forecast,” added the Treasury Lead. “This is something we still need to work on. MSF is now sometimes over hedged or underhedged. To accommodate this, I ask the entities to update the rolling forecast on a regular basis.”

For the future, MSF is considering hedging more than 80% of their budget, but this is dependent on further analysis and improved accuracy of the forecast and performing variance analysis comparisons on the forecast.

The introduction of a comprehensive FX risk management policy has also been crucial in giving MSF more control over their cashflows. By clearly defining stakeholder roles and responsibilities and emphasizing the principle of segregation of duties, MSF has introduced a centralized approach for managing their FX exposures. The group-wide FX hedging program promises significant financial and operational benefits. This strategic shift empowers MSF with greater control over its financial landscape. With a solid variance analysis mechanism on the horizon, MSF is assured to enhance cash flow forecasting and expand its FX hedging program with confidence.

Leverage our FX risk expertise

For organizations eager to navigate the complexities of FX risk and enhance their financial resilience, Zanders stands ready to share its insights and expertise. Contact us today to explore tailored strategies that can transform your financial operations and secure your organization's future. Together, let's unlock the potential of strategic FX management.

For more information, visit our NGOs & Charities page here, or contact Daan de Vries.

UGI International partnered with Zanders to transform their cash management by enhancing their Kyriba system and transitioning to Swift. This is how they boosted visibility and control over their complex, multinational cashflows.

When UGI International, a supplier of liquid gases across Europe and in the US, faced challenges in obtaining real-time visibility on its cash positions, they partnered with Zanders to elevate the performance of their Kyriba system. This started with the transition to the Swift banking system.

A quest for transparency

UGI International (UGI) is a leading supplier of liquid gases, operating under 6 brands across 16 countries. Every day, the business generates a consistent stream of high value and high volume in-country and cross-border transactions. This feeds into a complex network of disparate, multinational cashflows that the business’ treasury team is responsible for managing. When Nuno Ferreira joined as Head of Treasury in 2021, Kyriba was already in place, but it quickly became apparent that there was considerable scope to increase the use of the treasury management system to tackle persistent inefficiencies in their processes.

“Lack of visibility was one of our key issues,” says Nuno. “We didn't have access to accurate cash positions or forecasts, so we were lacking visibility on how much cash we had at the end of each specific day. The second thing was that the payment flows were very decentralized. In the majority of countries, payments were still being done manually.”

Lack of centralization was something that needed to be addressed and this demanded an overhaul of UGI’s approach to bank connectivity. The company’s use of the EBICS (Electronic Banking Internet Communication Standard) protocol had become a significant obstacle to them improving cash transparency and automating more of their payment processes. This was due to EBICS only allowing file exchanges with banks in a limited number of UGI European countries (France). Payments and transactions that extended beyond these geographies had to be managed separately and manually.

“We had Kyriba but because it was only connected with our French banks with EBICS it wasn’t able to serve all of the countries we operate in,” Nuno explains. “We recognized that going forward, to get the full software benefits from Kyriba, to reduce operational risk, and to get more visibility and control over our cashflows, we needed to connect our treasury management system to all of our main banks. These were the drivers for us to start looking for a new bank connectivity solution.”

The transition to Swift

The Swift (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication) banking system offered broader international coverage, supporting connectivity to all of UGI’s core banks across Europe and in the US. But making the transition to Swift was a substantial undertaking, requiring a multi-phased implementation to bring all of the company’s banks and payments onto the new protocol. Recognizing the knowledge of Swift and resource to oversee such a large project wasn’t available in their internal treasury team of 6 people, UGI appointed Zanders to bring the technical knowledge and capacity to support with the project.

“In this day and age, where a lot of technology is standard technology, what you get out of a TMS system depends on who helps you implement it, how much they listen to you, and how they adapt it to meet your needs,” explains Nuno. “You can find technical people easily now, but what we needed was an advisor that not only provides the technical implementation, but also helps with other areas—even if they are outside of the project. There is a lot of knowledge in Zanders about Swift and Kyriba but also about treasury in general. I knew if there were problems or issues, or even questions that fell outside of what we were implementing, there would always be someone at Zanders with knowledge in that specific area.”

This access to wider expertise was particularly relevant given there was not only a complex implementation to consider but also the compulsory Swift security attestation and assessment. The Swift Customer Security Controls Framework (CSCF) was first published in 2017 and is updated annually. This outlines a catalogue of mandatory and advisory controls designed to protect the Swift network infrastructure by mitigating specific cybersecurity risks and minimizing the potential for fraud in international transactions. Each year, all applicable users of the banking system must submit an attestation demonstrating their level of compliance with Swift’s latest standards, which must be accompanied by an independent assessment. This spans everything from physical security of IT equipment (e.g., storage lockers for laptops) and policies around processes (e.g., payment authorization) to IT system access (e.g., two-factor authentication) and security (e.g., firewall protection).

“We were not just talking about technical and system controls—we also needed to ensure that there were process controls in place,” says Nuno. “We didn’t have the right skillset to undertake this security assessment ourselves and we needed consultants to help us to provide the standalone reports showing that UGI follows best practices and has controls in place. This is where the second project came in. Zanders helped ensure everything was in place - the technical parts and the process parts - for the security assessment.”

Driving change, unlocking efficiency

With the migration to Swift, Zanders has been able to work with the UGI team to centralize their treasury processes, unlocking new functionality and elevated performance from their Kyriba system. This has dramatically reduced the manual effort demanded from the team to administer cash management.

“While before I was getting information from all the legal entities over Excel spreadsheets, now we don't need to reach out to our local entities to request this information – this information is centralized and automated,” explains Nuno. “This reduces operational risk because instead of uploading files or creating manual transfers within the online banking systems, it is fully integrated and so fully secured. Which also means we don't need to continuously monitor this process. This also reduces the manual activities and hence the number of FTEs required locally to run daily cash management processes. The intention was to have a secure straight-through processing of payments.”

The Swift security assessment facilitated by Zanders, not only ensured UGI achieved the baseline standards set by Swift, it also helped to raise awareness of Kyriba and the importance of security protocols both within treasury and in the IT and Security teams.

“Kyriba isn’t just a system to provide a report - if something goes wrong, it really goes wrong and creating this awareness was an added benefit,” says Nuno. “Doing this assessment forced us to make time to really look at our approach to security in detail. Internally, this prompted us to start discussing points that we would never normally address - simple things like closing your laptop when you’re away from your desk. This then starts to become part of the culture.”

The initial drivers behind the project were to tackle lack of visibility in UGI’s treasury systems. These outcomes were accomplished. The transition to Swift and the integration with the business’ Kyriba system has provided the accurate, real-time visibility on cash positions Nuno and the wider treasury team needed.

“When you don't have this visibility, you can’t manage your liquidity properly. There is value leakage and this impacts your P&L negatively on a daily basis,” says Nuno. “I now have this control and my cash position is accurate, so any excess cash or even FX exposure can be properly managed and generate higher yield to our shareholders.”

There is a lot of knowledge in Zanders about Swift and Kyriba but also about treasury in general. I knew if there were problems or issues, or even questions that fell outside of what we were implementing, there would always be someone at Zanders with knowledge in that specific area.

Nuno Ferreira, Head of Treasury at UGI

Advice delivered with commercial empathy

Overall, this project underscores the value of having an advisor that not only brings deep technical expertise to a project but also understands the realities of implementing treasury technology in a large, international corporate environment.

“One of the things I really liked was the flexibility of the Zanders team,” says Nuno. “They have a very structured approach, but it’s still flexible enough to take into account things that you cannot control - the unknown unknowns. They understand that within the corporate space, and with banks, it’s sometimes hard to predict when things are going to happen.”

This collaborative approach also unlocked additional unexpected benefits for the UGI team that will help them to continue to build on the Kyriba system performance and efficiency improvements achieved.

“The technical capability of our team has grown with these projects,” says Nuno. “From a technical standpoint, we now understand what we can do ourselves and how to do it, and when we need to go to Zanders for help. This knowledge transfer has enabled us to do a lot of things by ourselves that before we needed to go to an external partner for help with, and at the end of the day, this saves us costs.”

For more information, please contact our Partner Judith van Paassen.

In 2027, SAP will end its support for SAP ECC. Having spent years honing their ERP system to perfectly fit their business needs, this posed a challenge for Dutch network company Alliander – how and when to move to SAP S/4HANA.

There are risks in undertaking any big treasury transformation project, but the risks of not adjusting to the changing world around you can be far bigger. Recognizing the potential pitfalls of relying on an outdated (and soon to be unsupported) SAP ECC system, Alliander embarked on a large-scale, business-wide transition to SAP S/4HANA. Zanders advised on the Central Payments and Treasury phase of this project, which completed in May 2024.

A future-focused perspective

Network company, Alliander, is the Netherlands’ biggest decentralized grid operator, responsible for transporting energy to households and businesses, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. As a driving force behind the energy transition, the business is committed to investing in innovation - and this extends to how they are future-proofing their business operations as well as their contribution to shaping the sustainable energy agenda.

With their SAP ECC system approaching end of life, Alliander embarked on a company-wide switch to SAP S/4HANA. However, transitioning to SAP’s newest ERP platform is not just another simple upgrade, it’s a completely new system built on top of the software company’s own in-memory database HANA. For a business of Alliander’s size and complexity, this is a huge undertaking and a lengthy process. In order to minimize the disruption and potential risks to mission-critical business systems, Alliander has started the transition early, breaking down the implementation into a series of logically ordered phases. This means individual business areas are migrated to S/4HANA as separate projects.

“In finance, this transition started about four years ago with the transition of Central Finance to S/4—that was the first stepping stone,” says Thijs Lender, Financial Controller and Alliander’s Project Owner for SAP S/4HANA in Finance. “The second major project was Central Payments and Treasury. From a business point of view, this was the first real business finance process that we implemented on S/4.”

Central Payments and Treasury was selected as a critical gateway to moving other business areas to the new target infrastructure, for example, purchasing. It was also an ideal test ground for the migration process from ECC to S/4HANA as Alliander’s cash management processes operate in relative isolation, therefore presenting a lower risk of collateral damage across other business operations when the department moved to the new system. ''Treasury and Central Payments is at end of the of the source-to-pay and order-to-cash process—it’s paying our invoices and collecting money,” explains Guido Tabor, Digital Lead Finance at Alliander. “This means it could be moved to the target architecture without impacting other areas.”

Greenfield or brownfield?

The two most common pathways to SAP S/4HANA are a greenfield approach and a brownfield approach. For a brownfield migration a company’s existing processes are converted into the new architecture. In contrast, the greenfield alternative involves abandoning all existing architecture and starting from scratch. The second is a far more extensive process, requiring a business to often make wide-ranging changes to work practices, reengineering processes in order to optimally standardize their workflows. As Alliander’s business had changed significantly over the period of running SAP ECC, they recognized the benefit of starting from a clean slate, building their new ERP system from scratch to meet their future business needs rather than trying to retro fit their existing system into a new environment.

“We really wanted to bring it back to best practices, challenging them and standardizing our processes in the new system,” adds Thijs. “In the old way, we had some ways of working that were not standard. So, there were sometimes tough discussions, and we had to make choices in order to achieve standard processes.”

A collaborative approach

While the potential benefits of greenfield migrations are substantial, untangling legacy processes and building a new S/4HANA system from scratch is a complex undertaking. Success hinges on the collaboration of various stakeholders, including experts with understanding of the inner workings of the SAP architecture.

“From the very beginning, we didn't see this as an IT project,” Guido says. “IT was involved but also the business - in this case, finance from a functional perspective, and also Zanders and the Alliander technical team. It was really a joint collaboration.”

Zanders worked alongside Alliander right from the early stages of the Central Payments and Treasury project. From helping them to strategically assess their treasury processes through to planning and implementing the transition to SAP S/4HANA. Having worked with the business previously on the ECC implementation for Central Payments and Treasury, Zanders’ knowledge of Alliander’s current environments combined with their specialist knowledge of both treasury and SAP S/4HANA meant the team were well placed to guide the team through the migration process. The strength of the partnership was particularly important when the timing of the deployment was brought forward.

“Initially we wanted to go live shortly before quarter close” Guido recalls “Then at the beginning of January, we had a discussion with our CFO about the deployment. With June 1 being very close to June 30 half year close, we decided we didn't want to take the risk of going live on this date, and he challenged us to move it back to the middle of May.”

What became really important was having a partner [Zanders] who helps you think out of the box. What's the possibility? How can you deal with it? While also being agile in supporting on fast changes and even faster solutions.

Guido Tabor, Digital Lead Finance at Alliander.

Adopting a 'Fix It' mindset

With the new deadline set, the team were encouraged by the CFO to adopt a ‘fix it’ mindset. This empowered them to take a bold, no compromises approach to implementation. For example, they were resolute in insisting on a week-long payment freeze ahead of the transition, despite pleas for leniency from some areas of the business. This confident, no exceptions approach (driven by the ‘fix it’ mentality) ensured the transition was concluded on time leading to a seamless transition of Central Payments and Treasury to the new S/4HANA system.

“This was a totally new perspective for us,” says Guido. “With go live processes or transitions like this, there will be some issues. But it didn't matter what, it didn't matter how, we just had to fix it. What became really important was having a partner [Zanders] who helps you think out of the box. What's the possibility? How can you deal with it? While also being agile in supporting on fast changes and even faster solutions.”

Central Payments and Treasury project went live on S/4HANA in May 2024, on time and with a smooth transition to the new system.

“I was really happy on the first Monday after go-live and in that early week that there weren't big issues,” Guido says. “We had some hiccups, that's normal, but it was manageable and that's what is important.”

This project represented an important milestone in Alliander’s transition to SAP S/4HANA. Successfully and smoothly shifting a core business process into the new architecture clearly progressed the company past the point of turning back. This reinforced momentum for the wider project, laying robust foundations for future phases.

To find out how Zanders could help your treasury make the transition from SAP ECC to SAP S/4HANA, contact our Director Marieke Spenkelink.

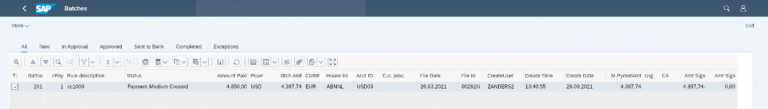

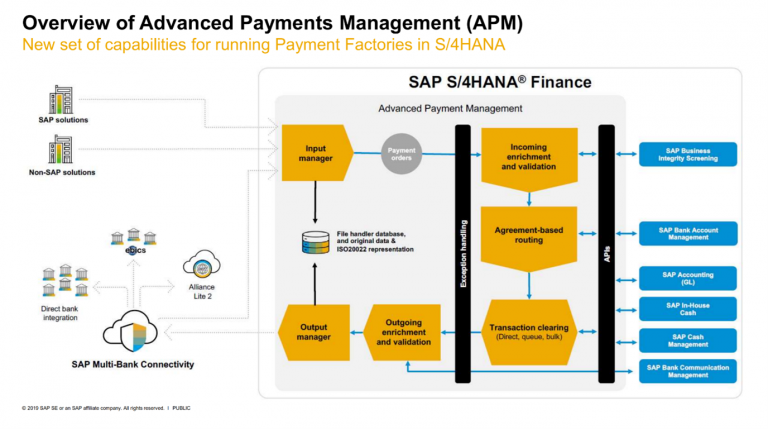

S/4 HANA Advanced Payment Management (APM) is SAP’s new solution for centralized payment hubs. Released in 2019, this solution operates as a centralized payment channel, consolidating payment flows from multiple payment sources. This article will serve to introduce its functionality and benefits.

Intraday Bank Statements offers a cash manager additional insight in estimated closing balances of external bank accounts and therefore provides the information to manage the cash more tightly on the company’s bank accounts.

Whilst over the previous years, many corporates have endeavoured to move towards a single ERP system. There are many corporates who operate in a multi-ERP landscape and will continue to do so. This is particularly the case amongst corporates who have grown rapidly, potentially through acquisitions, or that operate across different business areas. SAP’s Central Finance caters for centralized financial reporting for these multi-ERP businesses. SAP’s APM similarly caters for businesses with a range of payment sources, centralizing into a single payment channel.

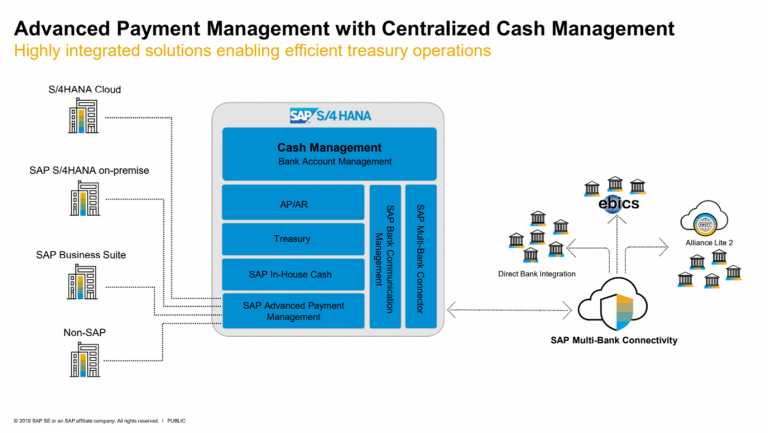

SAP APM acts as a central payment processing engine, connecting with SAP Bank Communication Management and Multi-Bank Connectivity for sending of external payment Instructions. For internal payments & payments-on-behalf-of, data is fed to SAP In-House Cash. Whilst at the same time, data is transmitted to S/4 HANA Cash Management to give centralized cash forecast data.

Figure 1 – SAP S/4 HANA Advanced Payment Management – Credit SAP

The framework of this product was built up as SAP Payment Engine, which is used for the processing of payment instructions at banking institutions. On this basis, it is a robust product, and will cater for the key requirements of corporate payment hubs, and much more beyond.

Building a business case

When building a business case for a centralized payment hub, it is important to look at the full range of the payment sources. This can include accounts payable/receivable (AP/AR) payments, but should also consider one-off (manual) payments, Treasury payments, as well as HR payments such as payroll. Whilst payroll is often outsourced, SAP APM can be a good opportunity to integrate payroll into a corporate’s own payment landscape (with the necessary controls of course!).

Using a centralized payment hub will help to reduce implementation time for new payment sources, which may be different ERPs. In particular, the ability of SAP APMs Input Manager to consume non-standard payment file formats helps to make this a smooth implementation process.

SAP APM applies a level of consistency across all payments and allows for a common payment control framework to be applied across the full range of payment sources.

A strength of the product is its flexible payment routing, which allows for payment routing to be adjusted according to the business need. This does not require specialist IT configuration or re-routing. It enables corporates to change their payment framework according to the need of the business, without the dependency on configuration and technology changes.

A central payment hub means no more direct bank integrations. This is particularly important for those businesses that operate in a multi-ERP environment, where the burden can be particularly heavy.

Lastly, as with most SAP products, this product benefits from native integration into modules that corporates may already be using. Payment data can be transferred directly into SAP In-House Cash using standard functionality in order to reflect intercompany positions. The richest level of data is presented to S/4 HANA Cash Management to provide accurate and up-to-date cash forecast data for Treasury front office.

Scenarios

SAP APM accommodates four different scenarios:

| Scenario | Description |

| Internal transfer | Payment from one subsidiaries internal account to the internal account of another |

| Payment on-behalf-of | Payment to external party from the internal account of a subsidiary |

| Payment in-name of | Payment to external party from the external account of a subsidiary. The derivation of the external account is performed in APM. |

| Payment in-name-of – forwarding only | Payment to external party from the external account of a subsidiary. The external account is pre-determined in the incoming payment instruction. |

A Working Example – Payment-on-behalf-of

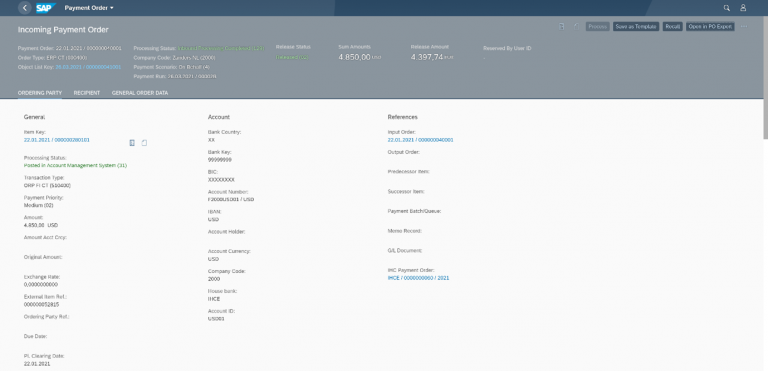

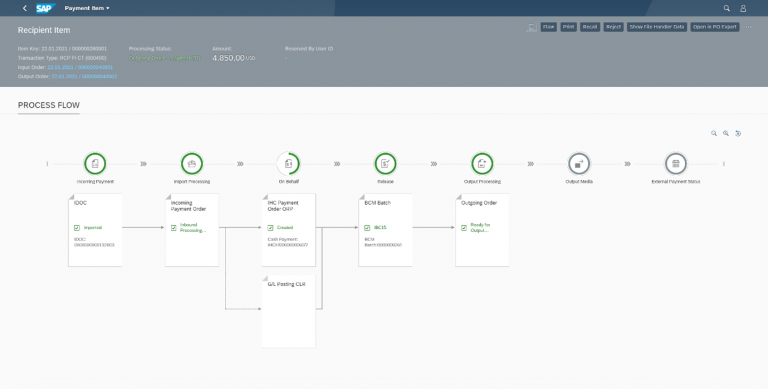

An ERP sends a payment instruction to the APM system via iDoc. This is consumed by the input manager, creating a payment order that is ready to be processed.

Figure 3 – Creation of Incoming Payment Order in APM

The payment order will normally be automatically processed immediately upon receipt. First the enrichment & validation checks are executed, which validate the integrity of the payment Instruction.

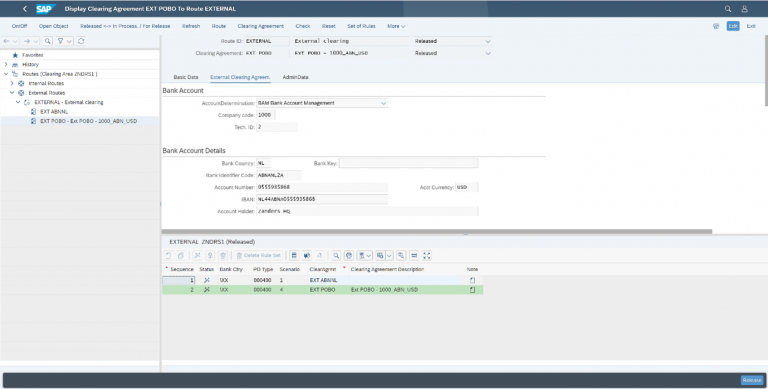

The payment routing is then executed for each payment item, according to the source payment data. The Payment Routing importantly selects the appropriate house bank account for payment and can be used to determine the prioritization of payments, as well as the method of clearing.

In the case of a payment-on-behalf-of, an external route will be used for the credit payment item to the third party vendor, whilst an internal route will be used to update SAP In-House Cash for the intercompany position.

Figure 4 – Maintenance of Routes

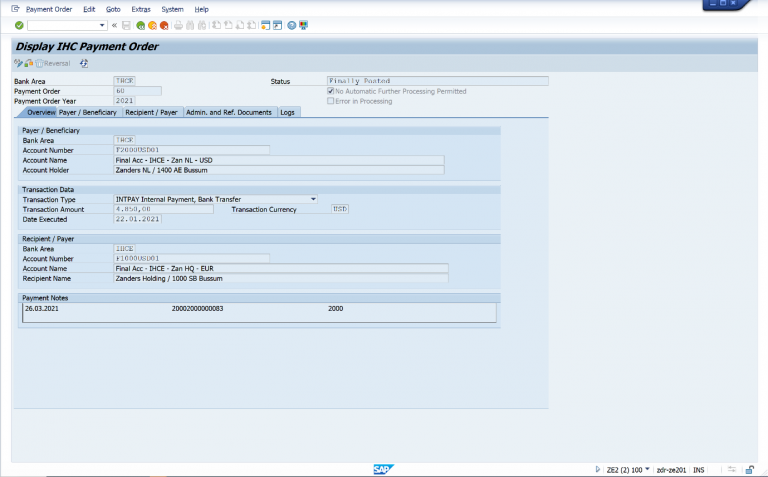

Clearing can be executed in batches, via queues or individual processing. The internal clearing for the debit payment item must be executed into SAP In-House Cash in order to reflect the intercompany position built up. The internal clearing for the credit payment Item can be fed into the general ledger of the paying entity.

Figure 5 – Update of In-House Cash for Payment-On-Behalf or Internal Transfer Scenarios

Outgoing payment orders are created once the routing & clearing is completed. At this stage, any further enrichment & validation can be executed and the data will be delivered to the output manager. The output manager has native integration with SAP’s DMEE Payment Engine, which can be used to produce an ISO20022 payment instruction file.

Figure 6 – Payment Instruction in SAP Bank Communication Management

The outgoing payment instruction is now visible in the centralized payment status monitor in SAP Bank Communication Management.

The full processing status of the payment is visible in SAP APM, including the points of data transfer.

Figure 7 – SAP APM Process Flow

Introduction to Functionality

SAP APM is comprised of 4 key function areas:

- Input manager & output manager

- Enrichment and validation

- Routing

- Transaction clearing

Figure 2 – SAP Advanced Payment Management Framework – Credit SAP

Input Manager

The input manager can flexibly import payment instruction data into APM. Standard converters exist for iDoc Payment Instructions (PEXR2002/PEXR2003 PAYEXT), ISO20022 (Pain.001.01.03) as well as for SWIFT MT101 messages. However, it is possible to configure new input formats that would cater for systems that may only be able to produce flat file formats.

Enrichment and Validation

Enrichment and validation can be used to perform integrity checks on payment items during the processing through APM. These checks could include checks for duplicate payment instructions. This feeds an initial set of data to S/4 HANA Cash Management (prior to routing) and can be used to return payment status messages (Pain.002) to the sending payment system.

Routing

Agreement-based routing is used to determine the selection of external accounts. This payment routing is highly flexible and permits the routing of payments according to criteria such as amounts and, beneficiary countries. The routing incorporates cut-off time logic and determines the priority of the payment as well as the sending bank account. This stage is not used for “forwarding-only” scenarios, where there is no requirement to determine the subsidiaries house bank account in the APM platform.

Clearing

Clearing involves the sending of payment data after routing to S/4 HANA Cash Management, in-house cash and onto the general ledger. According to selected route, payments can be cleared individually, or grouped into batches.

Further enrichment & validation can be performed, and external payments are routed via the output manager, which can re-use DMEE payment engines to produce payment files. These payment files can be monitored in SAP Bank Communication Management and delivered to the bank via SAP Multi-Bank Connectivity.

Royal FloraHolland launched the Floriday digital platform to enhance global flower trade by connecting growers and buyers, offering faster transactions, and streamlining international payment solutions.

In a changing global floriculture market, Royal FloraHolland created a new digital platform where buyers and growers can connect internationally. As part of its strategy to offer better international payment solutions, the cooperative of flower growers decided to look for an international cash management bank.

Royal FloraHolland is a cooperative of flower and plant growers. It connects growers and buyers in the international floriculture industry by offering unique combinations of deal-making, logistics, and financial services. Connecting 5,406 suppliers with 2,458 buyers and offering a solid foundation to all these players, Royal FloraHolland is the largest floriculture marketplace in the world.

The company’s turnover reached EUR 4.8 billion (in 2019) with an operating income of EUR 369 million. Yearly, it trades 12.3 billion flowers and plants, with an average of at least 100k transactions a day.

The floriculture cooperative was established 110 years ago, organizing flower auctions via so-called clock sales. During these sales, flowers were offered for a high price first, which lowered once the clock started ticking. The price went down until one of the buyers pushed the buying button, leaving the other buyers with empty hands.

The Floriday platform

Around twenty years ago, the clock sales model started to change. “The floriculture market is changing to trading that increasingly occurs directly between growers and buyers. Our role is therefore changing too,” Wilco van de Wijnboom, Royal FloraHolland’s manager corporate finance, explains. “What we do now is mainly the financing part – the invoices and the daily collection of payments, for example. Our business has developed both geographically and digitally, so we noticed an increased need for a platform for the global flower trade. We therefore developed a new digital platform called Floriday, which enables us to deliver products faster, fresher and in larger amounts to customers worldwide. It is an innovative B2B platform where growers can make their assortment available worldwide, and customers are able to transact in various ways, both nationally and internationally.”

Our business has developed both geographically and digitally, so we noticed an increased need for a platform for the global flower trade

Wilco van de Wijnboom, Royal FloraHolland’s Manager Corporate Finance

The Floriday platform aims to provide a wider range of services to pay and receive funds in euros but also in other currencies and across different jurisdictions. Since it would help treasury to deal with all payments worldwide, Royal FloraHolland needed an international cash management bank too.

Van de Wijnboom: “It has been a process of a few years. As part of our strategy, we wanted to grow internationally, and it was clear we needed an international bank to do so. At the same time, our commercial department had some leads for flower business from Saudi-Arabia and Kenya. Early in 2020, all developments – from the commercial, digital and financing points of view – came together.”

RFP track record

Royal FloraHolland’s financial department decided to contact Zanders for support. “Selecting a cash management bank is not something we do every day, so we needed support to find the right one,” says Pim Zaalberg, treasury consultant at Royal FloraHolland. “We have been working together with Zanders on several projects since 2010 and know which subject matter expertise they can provide. They previously advised us on the capital structure of the company and led the arranging process of the bank financing of the company in 2017. Furthermore, they assisted in the SWIFT connectivity project, introducing payments-on-behalf-of. They are broadly experienced and have a proven track record in drafting an RFP. They exactly know which questions to ask and what is important, so it was a logical step to ask them to support us in the project lead and the contact with the international banks.”

Zanders consultant Michal Zelazko adds: “We use a standardized bank selection methodology at Zanders, but importantly this can be adjusted to the specific needs of projects and clients. This case contained specific geographical jurisdictions and payment methods with respect to the Floriday platform. Other factors were, among others, pre-payments and the consideration to have a separate entity to ensure the safety of all transactions.”

Strategic partner

The project started in June 2020, a period in which the turnover figures managed to rebound significantly, after the initial fall caused by the corona pandemic. Van de Wijnboom: “The impact we currently have is on the flowers coming from overseas, for example from Kenya and Ethiopia. The growers there have really had a difficult time, because the number of flights from those countries has decreased heavily. Meanwhile, many people continued to buy flowers when they were in lockdown, to brighten up their new home offices.”

Together with Zanders, Royal FloraHolland drafted the goals and then started selecting the banks they wanted to invite to find out whether they could meet these goals. All questions for the banks about the cooperative's expected turnover, profit and perspectives could be answered positively. Zaalberg explains that the bank for international cash management was also chosen to be a strategic partner for the company: “We did not choose a bank to do only payments, but we needed a bank to think along with us on our international plans and one that offers innovative solutions in the e-commerce area. The bank we chose, Citibank, is now helping us with our international strategy and is able to propose solutions for our future goals.”

The Royal FloraHolland team involved in the selection process now look back confidently on the process and choice. Zaalberg: “We are very proud of the short timelines of this project, starting in June and selecting the bank in September – all done virtually and by phone. It was quite a precedent to do it this way. You have to work with a clear plan and be very strict in presentation and input gathering. I hope it is not the new normal, but it worked well and was quite efficient too. We met banks from Paris and Dublin on the same day without moving from our desks.”

You only have one chance – when choosing an international bank for cash management it will be a collaboration for the next couple of years

Wilco van de Wijnboom, Royal FloraHolland’s Manager Corporate Finance

Van de Wijnboom agrees and stresses the importance of a well-managed process: “You only have one chance – when choosing an international bank for cash management it will be a collaboration for the next couple of years.”

Future plans

The future plans of the company are focused on venturing out to new jurisdictions, specifically in the finance space, to offer more currencies for both growers and buyers. “This could go as far as paying growers in their local currency,” says Zaalberg.

“Now we only use euros and US dollars, but we look at ways to accommodate payments in other currencies too. We look at our cash pool structure too. We made sure that, in the RFP, we asked the banks whether they could provide cash pooling in a way that was able to use more currencies. We started simple but have chosen the bank that can support more complex setups of cash management structures as well.” Zelazko adds: “It is an ambitious goal but very much in line with what we see in other companies.”

Also, in the longer term, Royal FloraHolland is considering connecting the Floriday platform to its treasury management system. Van de Wijnboom: “Currently, these two systems are not directly connected, but we could do this in the future. When we had the selection interviews with the banks, we discussed the prepayments situation - how do we make sure that the platform is immediately updated when there is a prepayment? If it is not connected, someone needs to take care of the reconciliation.”

There are some new markets and trade lanes to enter, as Van de Wijnboom concludes: ”We now see some trade lanes between Kenya and The Middle East. The flower farmers indicate that we can play an intermediate role if it is at low costs and if payments occur in US dollars. So, it helps us to have an international cash management bank that can easily do the transactions in US dollars.”

One of the main challenges treasurers face when setting up a cash pool or an in-house bank is setting an appropriate interest rate for the resulting transactions. This topic, among others, has been addressed in the recently published OECD transfer pricing guidelines on financial transactions. As expected, the OECD has left it to the taxpayers and advisors to translate the guidance into concrete methodologies for compliance. Zanders has designed a cloud-based solution that automates the entire process.

The pricing of intercompany treasury transactions is subject to transfer pricing regulation. In essence, treasury and tax professionals need to ensure that the pricing of these transactions is in line with market conditions, also known as the arm’s length principle, thereby avoiding unwarranted profit shifting.

We have has been assisting dozens of multinationals on this topic through our Transfer Pricing Solution (TPS). The TPS enables them to set interest rates on intercompany transactions in a compliant and automated way. Since its go-live, clients have priced over 1000 intercompany loans with a total notional of over EUR 60 billion using this self-service solution.

Cash Pooling Solution

In February 2020, the OECD published the first-ever international consensus on financial transactions transfer pricing. One of the key topics of the document relates to the determination of internal pooling interest rates. As a reaction, Zanders has launched a co-development initiative with key clients to design a Cash Pooling Solution that determines the arm’s length interest rates for physical cash pools, notional cash pools and in-house banks.

The goal of this new solution is to present treasury and tax professionals with a user-friendly workflow that incorporates all compliance areas as well as treasury insights into the pooling structure. The three main compliance areas for treasury professionals are:

- Ensuring that participants have a financial incentive to participate in the pooling structure. Entities participating in the pool should be ‘better off’ than they would be if they went directly to a third-party bank. In other words, participants’ pooled rates should be more favorable than their stand-alone rates. The OECD sets out a step-by-step approach to improve interest conditions for participating entities to distribute the synergies towards the participants.First, the total pooling benefit should be calculated. This total pooling benefit is the financial advantage for a group compared to a non-pooled cash management set-up. The total pooling benefit can be broken down into a netting benefit and an interest rate benefit. The netting benefit arises from offsetting debit and credit balances. The interest rate benefit arises from more beneficial interest rate conditions on the cash pool or in-house bank position, compared to stand-alone current accounts.

Once the total pooling benefit has been calculated, it should be allocated over the leader entity and the participating entities. Therefore, a functional analysis of the pooling structure should be made to identify which entities contribute most in terms of their balances, creditworthiness and the administration of the pool. The allocated amount should be priced into the interest rates. A deposit rate will thus receive a pooling premium. A withdrawal rate will incorporate pooling discount. - Ensuring a correct tax treatment of the cash pool transactions. Pooling structures are primarily in place to optimize cash and liquidity management. Therefore, tax authorities will expect to see the balances of cash pool participants fluctuate around zero. Treasury professionals should monitor positions to prevent participants from having a structural balance in the pool. If the balance has a longer-term character, tax authorities can classify such pooling position as a longer-term intercompany loan. Consequently, monitoring structural balances can lower tax risk significantly.

- Appropriate documentation should be in place for each time treasury determines the pooling interest rates. The documentation should include the methodology as well as all specifics of the transfer pricing analysis. Proper documentation will enable the multinational to substantiate the interest rates during tax audits.

Multinationals are confronted with a significant compliance burden to comply with these new guidelines. Different hurdles can be identified, ranging from access to the appropriate market data to a considerable and recurring time investment in determining and documenting the internal deposit and withdrawal rates for each pooling structure.

It remains to be seen how auditors treat these new guidelines, but the recent increased focus on transfer pricing seems to indicate that this will be a topic that may need additional attention in the coming years.

Zanders Inside solutions

In order to support treasury and tax professionals in this area, Zanders Inside launched its cloud-based Cash Pooling Solution. This solution will focus on each of the three compliance areas as described above. In addition, the solution leverages a high degree of automation to support the entire end-to-end process. It offers a cost-effective alternative for the manual process that multinationals go through. Please watch our video showing how the Cash Pooling Solution tackles the challenge of OECD compliancy.

We asked Marcel Pels how insurers are coping with today’s fast-moving developments in payment traffic. As Manager Back-office Treasury & Cash Management at Achmea, he deals with cash management at the Achmea organization on a daily basis.

“The biggest challenge in the area of cash management is, and will remain, obtaining good information about the expected cash flows to make the best possible liquidity forecasts in the short and long term,” reveals Marcel. “The current trend is that banks can do their payments and bookings 24/7 – even at weekends. Thanks to instant payments, bank payments from private individuals are debited and credited within a few seconds. That will also happen in business. For Achmea this acceleration means that the claims of insured parties can be paid even quicker. From a cash management and treasury perspective, you have to make sure that enough money is available to make these payments, but at the same time you don't want to be holding too much cash, as it actually costs money to have too much of a credit balance. The biggest challenge is establishing an optimal forecast of the incoming and outgoing cash flows, and of the balances of our accounts, so that we can do our payments at any moment.”

The market has become increasingly volatile, with new developments quickly following one another. How do you achieve accurate cash flow forecasting in the medium term?

“We receive forecasts from all the business units every month – for instance of Zilveren Kruis health insurances, FBTO health insurances, and Achmea’s Non-life, Pension and Life insurances. For every type of flow - premium, value transfers, benefits, proxies, costs etc. - monthly forecasts are made 18 months in advance. All flows are linked to specific bank accounts that also provide insight into the expected bank stocks for the next 18 months. The forecasts are entered into our cash management system, Cash & Liquidity Management from Serrela (CLM), the first two months on a daily basis and the remaining 16 months on a monthly basis. In addition to the forecasts of the business, our treasury management system, SAP TRM, also includes the expected cash flows from the treasury activities in CLM. Together with the actual banking positions, our Treasury can always look ahead for 18 months to the expected banking positions and look back at the actual stocks. During a month, the forecasts are regularly adjusted for the coming days of the month in cooperation with the business. The business itself has permission to look in CLM at both the actual cash flows and the expected cash flows. After each month, a post calculation is made by the cash manager, in which the forecasts are compared with the actual cash flows. In case of large differences, the business must issue a statement for this and, if necessary, adjust the upcoming forecasts. It’s therefore about continuous alignment with the business.”

Achmea started implementing a new TMS some six years ago. What changes did this herald for Achmea’s cash-management activities and cash position?

“We use SAP TRM for all treasury activities and Serrala CLM for cash management. Since the implementation of both systems, a lot of work has become simpler and more efficient and we can more easily extract information from both systems.”

To what extent do legislation and regulations influence cash management at Achmea?

“We take the regulations of the banks into account, such as Basel III and the Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2). Under Basel III, for example, the debit and credit positions in a cash pool cannot be settled with each other. As a result, the debit positions are seen as lending and banks therefore have to keep more equity on their balance sheets. The extra costs for this will be charged by the banks to customers who make use of this pooling technique. This affects all major legal entities of Achmea. In this context, cash management will regularly top off high credit balances and replenish high debit balances of accounts in a cash pool. The introduction of PSD2 brings changes in the area of access to the payment account. To this end, the banks are following an open banking strategy whereby they develop new services in combination with the opening obligation of customer information. For this purpose, an API (Application Programming Interface) can be used, which makes it possible for us to retrieve information from the banking systems. Instead of the SWIFT MT940/MT942 electronic account statements, we are now investigating whether we can harvest the necessary information differently, using APIs.”

And what exactly are the advantages of APIs?

“They allow us to obtain information from our banks quicker and more accurately, which in turn enables us to determine a more up-to-date cash position for cash management. We also investigated whether an API can retrieve all past statement transactions distributed over a day and replace the complete daily statement the next morning. This way, the financial administrations can handle all mutations and spread a day’s workload more efficiently.”

What is your own prognosis for the future of insurers?

“Thanks to new technology it’s possible to obtain far more information much quicker than before. IT systems within the financial sector are more open to sharing information and communicating externally. Processes can thus be arranged more efficiently. Insurers can use this information to better serve customers and to develop new products and services.”

IUCN’s transformation towards a unified global cash management approach helped streamline banking relationships and improve visibility, supporting its mission to address global conservation challenges more efficiently.

In 2014, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) launched their Global Cash Management Project in order to improve cash management policies and processes throughout the organization. IUCN chose Zanders as their trusted advisor to support them on the journey.

IUCN was founded in 1948 and is composed of 1,300 members, including governments and non-governmental organizations. The ability to convene diverse stakeholders and provide the latest science and on-the-ground expertise drives IUCN’s mission of informing and empowering conservation efforts worldwide. IUCN’s work is centered on three key areas: promoting effective and equitable governance of nature’s use, nature-based solutions to global challenges, and valuing and conserving nature.

Combatting the Challenges

From their 40 locations around the world, IUCN works together with local partners to use nature-based solutions to combat the challenges arising from climate change, loss of biodiversity, and food and water security. IUCN is active on an international level, seeking to influence policymakers and governance mechanisms. On a national and local level, they advise governments and stakeholders on translating international commitments into applicable policies and frameworks. Through a network of some 16,000 experts, IUCN gathers and generates knowledge for publicly available databases managed by IUCN. One such database is the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, which gives an assessment of the extent a species is threatened and an indication of the extinction risk, thereby promoting conservation.

Fragmented Treasury Management Approach

The local nature of IUCN’s project work is reflected in their organizational structure with 32 country offices and 9 regional offices. This has historically given a great deal of independence to the local finance departments in IUCN. “Our regional offices and local offices have a great deal of autonomy, and as a result, finance has followed that autonomy, so each office essentially has its own finance function,” Mike Davis, chief financial officer for the Global IUCN Secretariat, explains.

The decentralized and autonomous nature of the finance department led to a fragmented treasury management approach with each local office taking on cash management and foreign exchange activities themselves. This resulted in a lack of visibility of the global cash position, decentralized collections of donations, and inefficient foreign exchange management performed locally.

Transformation

During the last few years, IUCN transitioned from directing the disparate operations and initiatives across the organization towards a more global and unified approach. “We are moving towards a more integrated organization,” says Davis. “For example, when considering climate change, a global approach is taken with initiatives translating into global programs implemented in several countries, as opposed to each region or each country developing its own projects on a local level. This also impacts how you then organize and manage your resources, which then has an impact on the treasury function as well.”

To support this transformation, IUCN implemented one common Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system across their entire organization, which replaced the stand-alone systems used in the local offices around the world. From a treasury perspective, the rollout of the ERP system was the first step towards creating better visibility of the total cash position in the organization.

Global Cash Management Project

Further integration between the global finance operations was initiated when IUCN launched their global cash management project. Zanders supported IUCN by charting a new cash management course to provide insights into market best practices and strategic guidance on future-proofing bank relationship management. Zanders began by conducting a thorough study of the cash management processes at IUCN to create a report of improvement initiatives. The primary recommendations were for the IUCN Finance Department to implement a uniform cash management policy across the organization and to rationalize their broad, diverse, and costly banking portfolio. Davis: “We chose Zanders because of their expertise in treasury and good reputation among other international organizations.”

Bank Rationalization Initiatives

The IUCN banking portfolio consisted of 46 banks and a dispersed bank account structure with approximately 160 bank accounts. The growing bank portfolio inhibited the visibility and control of cash. Furthermore, the dominance of local autonomy and a decentralized organization left IUCN with an inability to leverage banking relationships between the global secretariat, regional, and country offices. IUCN had an ineffective banking structure with regards to the number of bank accounts, service level, and competitiveness on fees provided by the banking partners. Additionally, the magnitude of bank accounts had operational maintenance and management implications because they required excessive manual time and effort to maintain. Introducing a banking landscape that supports efficient processes and reduces internal costs spent on maintaining bank accounts were key objectives for the bank rationalization initiatives. “Our main objective was to have efficient processes and to rationalize our banking structure because with that you can reduce risk, the amount of time in your organization spent on managing different relationships and also reduce the number of bank accounts. As each bank account has an internal cost, I would say the internal costs were far more important to us than the external costs,” Davis says.

Request for Information

By the end of 2015, IUCN issued, with the support of Zanders, a Request for Information (RFI) to eight banks identified to either have a global reach and footprint matching IUCN requirements or otherwise be material for IUCN. In total, 51 countries were included in the RFI. The RFI invited banks with global and regional capabilities to elaborate on their cash management offerings which were relevant for the business and geographical areas of IUCN. This included the services offered for cash management, payment processing, foreign currency disbursement, reporting capabilities, and connectivity solutions. Davis explains: “The Zanders team was very helpful throughout the whole process and very willing to adapt their services to what we needed and to think about different approaches before advising on what would be the best approach for us. We chose a more agile path with the RFI route, as opposed to a more formal RFP, which was then adjusted so it best met our needs and budget.”

Local Offering, Global Presence

To best facilitate and run nature conservation projects around the world, IUCN organizes itself in 9 regions; Asia, West Asia, Eastern & Southern Africa, West & Central Africa, Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Mexico Central America & Caribbean, Oceania, and South America. This localized, regional structure played a significant role in determining IUCN’s new banking landscape.

“Compared to other international organizations, IUCN has formed their regions in a much more localized manner, which then also becomes key when rationalizing and selecting new global banking partners as one has to balance the local offering with the global presence,” says Liam Ó Caoimh, director at Zanders.

Preferred Banking Partners

IUCN received RFI responses from five international banks. A six-sigma scoring and evaluation tool assessed the five proposals, which IUCN and Zanders evaluated together. IUCN used the results of the assessment to select three banks as the preferred choice for international banking partners. These three banks together cover 70 percent of the countries in scope for IUCN. For the secretariat’s headquarters in Switzerland, the bank relationship was kept with IUCN’s existing Swiss banking partner. By reducing the broad banking landscape to a manageable portfolio of relationships, IUCN’s treasury focuses more on supporting the field offices around the world under the guidance of a lean yet strong global cash management framework.

Would you like to know more? Contact us today.

Following a rigorous treasury transformation and global SAP implementation, British American Tobacco launched a project to further streamline its cash management structure and processes, including the introduction of a ‘receivables on behalf of’ structure optimized with virtual accounts.

British American Tobacco (BAT), headquartered in the UK and listed on the London Stock Exchange, is well known as the manufacturer of traditional cigarette brands as well as next generation products such as e-cigarettes. The company, which had a gross turnover of £42 billion in 2015 and employs 50,000 people across its manufacturing operations in 41 countries, is known for its commitment to operating responsibly and with transparency.

BAT recently completed the deployment of project ‘TaO’ which introduced a new target operating model enabled by one instance of SAP across all markets within the group. TaO is the enabler to migrate more processes to financial shared service centers and for the operation of a more centralized treasury function, resulting in greater visibility and control over the group’s cash resources.

Throughout the TaO project, Zanders advised BAT on how to restructure its treasury processes, which were overhauled and pushed towards a centralized model. And, as the company invested in its treasury and cash management infrastructure, the logical next step was to build on the foundation TaO provided to move from elements of best practice to world class cash management.

The TaO project highlighted the potential to increase efficiencies in payables and receivables by channeling payments through ‘on behalf of’ (OBO) structures, Phil Stewart, global head of cash and banking at BAT, says: “The ‘payments/receivables on behalf of’ (POBO/ROBO) structure was a key component of the cash management optimization initiative. These structures leveraged the in-house bank implemented during TaO, allowing for greater transparency, control and risk management while using established SAP channels for the most efficient and cost effective transaction routing.”

The ROBO challenge

BAT is an early adopter for best practices in the cash management and payments space, and in the case of OBO, BAT needed a bank that supported them in this relatively new area. Zanders director Arn Knol says: “POBO isn’t a new concept but this project focused on using virtual accounts to enable ROBO, replacing actual bank accounts with virtual accounts. This meant that each customer had to be assigned a unique virtual account – enabling BAT to see exactly when customers have paid and to replace physical bank accounts with virtual ones.”

One benefit of a ROBO structure is a clear reference for each receivable in central treasury, with data about the payment, which smooths the reconciliation process for receivables. The company also drastically reduces the number of bank accounts for further cost savings and more efficient use of staff time. The efficient processing and reconciliation of receivables also improves the day’s sales outstanding (DSO) process.

There was, however, a challenging aspect to the project: not all banks BAT spoke to were ready to meet the company’s requirements. Stewart says: “One of the challenges we faced was that the banks’ virtual account offerings were at different stages of maturity with very few able to support the model we wanted to deploy. We were able to overcome this to achieve a bespoke solution that worked for us on a consistent basis across all markets in scope. The virtual account space continues to evolve at pace, it is worth noting that a number of banks have made significant strides and are now better placed to meet our requirements.”

Concept and implementation

BAT started the OBO project in January 2016, initially working on a conceptual design for a number of pilot markets. The company’s Asia-Pacific business took on the pilot phase and chose to implement OBO in Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand. These countries had already rolled out the TaO project successfully and, from a regulatory perspective, had few barriers to adopting the structure.

BAT had already carried out due diligence in these markets prior to the start of the TaO project, including in-depth discussions with tax and legal experts, as well as with central banks. During the impact analysis for the OBO project, the company built on this knowledge, adding further technical analysis to identify what information SAP needed. Stewart says: “The conversations we had with Zanders at this stage were invaluable in shaping how BAT wanted to use virtual accounts to simplify account structure and enhance receivables process. They provided a high level of expertise, which enabled us to finalize the design at an early stage. This was key to the project’s success and timely implementation.”

BAT chose Deutsche Bank as the main banking partner for the Asia-Pacific pilot project. Communication between the company and the bank was crucial at this stage and facilitated the discussions. Knol explains: “The onsite meetings during the pilot phase helped to make sure that Deutsche Bank really understood what BAT wanted from a technical perspective. We played an important role in bridging any gaps between the bank and BAT.” Once the team was satisfied that the pilot phase was a success, they implemented the OBO structure with Deutsche Bank in Western Europe in the second half of 2016. Stewart says: “SEPA was the catalyst to effectively deploy OBO across Western Europe and, while the payments environment is more standardized than Asia-Pacific, the number of countries involved in the roll-out brought additional complexity to the project. We had to be clear in communicating the change in conjunction with getting the necessary legal and tax sign off from all markets. Although it’s to be expected that there will be some challenges, particularly from an IT point of view, all areas of the company were actually very supportive and fully bought into the new way of working.”

Business case for OBO

The business drivers for the project were centralization, simplification through standardization, rationalization, transparency, consistency and cost/risk reduction. The OBO structure supports treasury by increasing shared service efficiency and enhancing reconciliation processes, improving bank relationship management, consolidating banks and bank accounts, reducing fees, increasing yields and simplifying liquidity structures.

“The end result surpassed our expectations,” says Stewart. “One key factor was that our stakeholders were very aware of what impact the project would have from the outset. We ensured that our treasury, procure-to-pay and order-to-cash objectives were fully aligned. All corners of the business understood the benefits of the implementation and rather than wondering why we were doing it, they actually wondered why we hadn’t done it sooner.”

Working with the business units enabled the various stakeholders within BAT to understand the value of the project. According to Knol, BAT explored additional opportunities because it was clear that treasury was a valued partner for parts of the organization, such as procurement and the financial shared service center.

This acceptance allowed BAT to continue with the OBO project and roll it out in other markets. Stewart adds: “We certainly saw this as a wider cross-functional project supporting a number of other group wide centralization and working capital initiatives, rather than looking at it solely through a treasury lens.”

Handling complexity