With increasing regulatory expectations and evolving market dynamics, a well-structured ALM framework is essential for effective banking book risk management.

Managing banking book risk remains a critical challenge in today’s financial markets and regulatory environment. There are many strategic decisions to be made and banks are having trouble applying homogeneous hedging approaches across their balance sheet. As shown in the EBA’s IRRBB implementation heatmap of last February, hedging strategies and NMD modeling practices still vary significantly between banks. In addition, the EBA expects future developments on CSRBB and DRM. Meanwhile, behavioral risks and rapidly changing interest regimes need to be addressed, while balancing the stability of net interest income and economic value.

Treasury departments are at the heart of managing the banking book, with their ‘ALM framework’ serving as the essential blueprint for banking book management. This framework ensures alignment between risk appetite and business objectives. A well-developed ALM framework provides better insights and enhances understanding of the balance between risk and performance.

But, what are the characteristics of a mature ALM framework? What steps can be taken to elevate the maturity of the framework? And how can your framework unlock your full potential? This article explores the components that make up an effective ALM framework and describes what an advanced setup looks like. After inspecting ALM governance, risk frameworks, hedging strategies, ALM modeling and capital & performance management, we offer the opportunity to benchmark the maturity of your own framework against other banks and the ideal setup by filling out this survey.

Governance

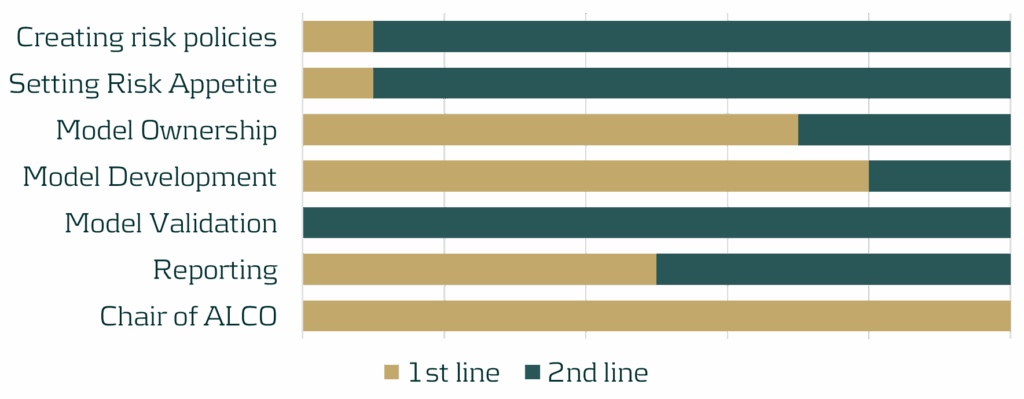

The cornerstone of any effective ALM framework is appropriate governance, much like any well-functioning business activity. Setting up strong governance begins with defining a charter with a clear scope and mandate for the departments involved. It is crucial that the first and second line of defense have accurately defined roles and pro-active knowledge sharing needs to be the standard. Oversight by senior management is essential across all activities within the framework and the Asset-Liability Committee (ALCO) should be composed of members from treasury, risk and the business.

Figure 1: Distribution of roles and responsibilities of the first and second line, based on a survey performed by Zanders.

Another critical element of ALM governance is the ALM strategy and the associated policies. The ALM strategy covers how risk and return are balanced, what interest rate position is ideal and how risks are operationally hedged (granularity, frequency and instruments). Typically, banks operate most effectively when the strategy is owned by the treasury department. The strategy should integrate perspectives on interest rate risk, credit spread risk, (intraday) liquidity risk, FX risk and capital, and must be fully aligned with business objectives and overall risk appetite.

The second line should manage the translation of the strategy into comprehensive risk policies covering the same risk types and ensuring alignment with both global and local regulatory frameworks. As part of the overarching policy framework, a risk identification process must highlight emerging risk and feed into the Risk Appetite Setting (RAS). In turn, the RAS needs to define KPIs for guiding daily risk management, specifying the boundaries within which the first line can balance risk and return.

Risk Framework

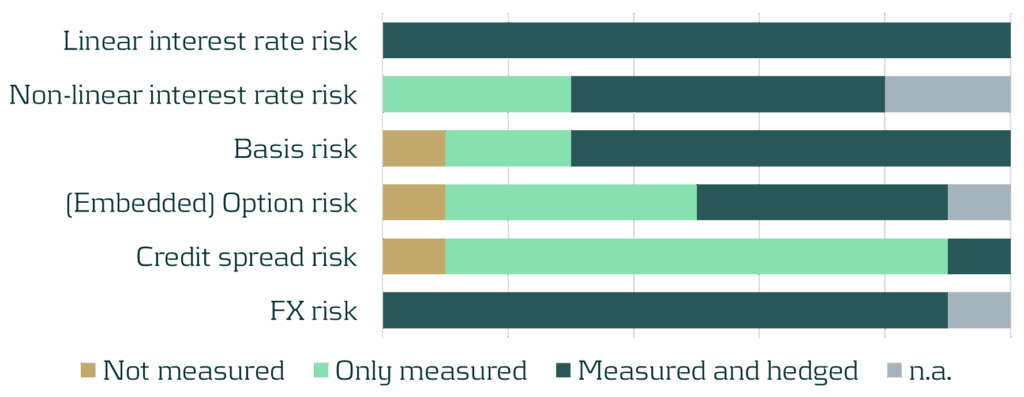

Beyond sound governance, risk policies are integral to the broader risk framework. Within this framework, it is crucial to make informed decisions on measuring and hedging each individual risk type. Ideally, all risk types are managed within a central ALM system that supports risk dashboarding and stress testing.

Figure 2: Risk- scope for a selection of sub-risk types, based on a survey performed by Zanders.

In addition to identifying relevant risks and determining appropriate responses, it is essential to establish an internal operational framework for ongoing management. Centralizing and netting risks in central treasury books is fundamental to an efficient treasury function. While several approaches exist, internal transactions are typically preferred, as they enable accurate measurement of risks over different commercial and/or geographical portfolios.

The strategy for managing interest rate risk in the banking book should ultimately be reflected in a clearly defined target duration of equity. Segregating the structural position into a dedicated book facilitates precise monitoring and agile adjustments to market dynamics and regulatory changes. Market volatility may necessitate revisiting the target based on interest rate expectations, and many banks have been adjusting their target durations accordingly. The structural position is a critical strategic choice in the trade-off between earnings and value stability, and is thereby an essential factor in the hedge strategy.

Hedge Strategy

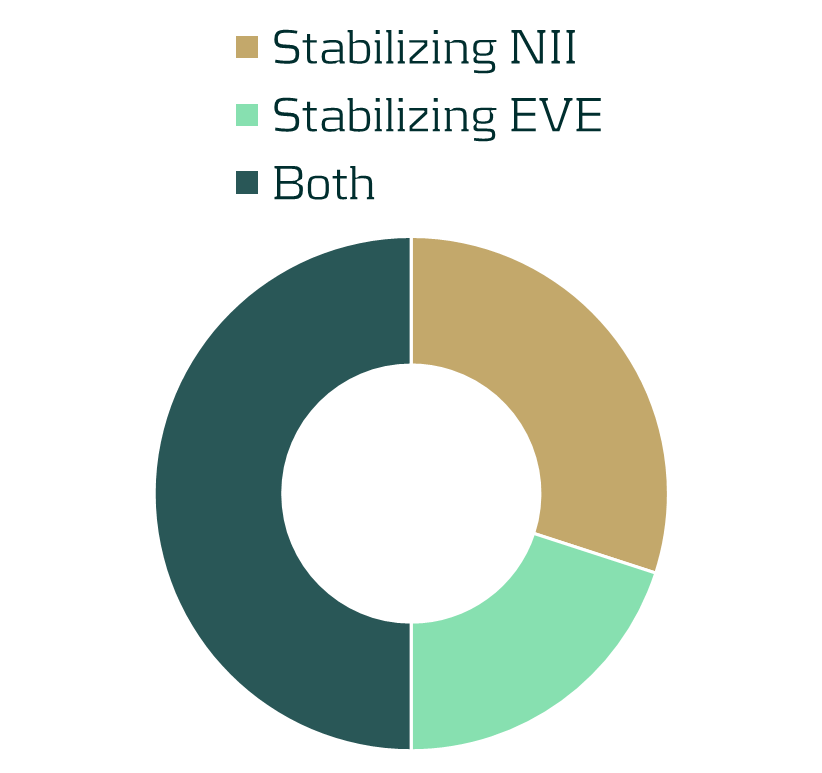

With the risk framework, the treasury strategy, and risk appetite statement as its foundation, a strategy for hedging must be defined. This strategy guides first line processes, stating clear objectives on both earnings and value stability. Striking a balance between these two elements is challenging, but forms the basis for optimizing the balance sheet. The decision to include or exclude margins should be consistent across cashflows and discounting and should be aligned with the primary hedging focus, whether it is stabilizing earnings or value.

Figure 3: Focus of hedging strategies, based on a survey performed by Zanders.

The scope of the hedging strategy must be consistent with the risk scope outlined in the risk framework and encompass the entire balance sheet. The strategy needs to address linear risks, and also explicitly account for non-linear risks that may arise due to convexity or behavioral factors.

While commercial books typically have the objective to stabilize or increase net margins without taking an active position, hedging must be an active steering process. The treasury function should focus on optimizing the economic value of equity and net interest income within defined target limits. It is essential for the hedging process to be dynamic, using real-time analytics to proactively identify opportunities for improvement as market conditions and expectations change. Banks need to make use of scenario planning and predictive modeling to anticipate hedge requirements and adapt accordingly.

Modeling

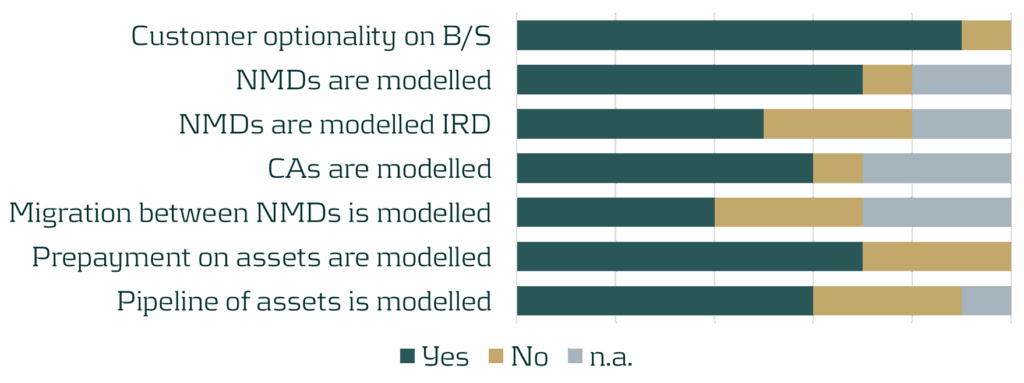

Hedging practices are based on the outcomes of a bank’s models, which should reflect reality as close as possible. A challenging yet essential aspect to modeling is addressing the optionalities inherent to many financial products. These embedded optionalities need to be modeled consistently for all assets and all liabilities. Ideally, banks have advanced interest rate-dependent behavioral models in place to model the interest rate sensitivity of deposits and loans. Pipeline risk, the migration between different deposit types and potential other behavioral characteristics of products also need to be modelled. These models provide banks with realistic insights into expected cashflows. As customer behavior can vary significantly under different market conditions, banks benefit greatly from simulating and analyzing these changes using stochastic models.

Figure 4: Type of behavioral modeling performed by banks, based on a survey performed by Zanders.

From a liquidity perspective, it is important for banks to use consistent methodologies for short and long-term cashflow forecasting. Additionally, integrating liquidity models, such as those for LCR and NSFR, with liquidity stress testing, offers valuable insights into potential future liquidity needs.

Machine learning is gaining more and more traction within the field of ALM and is becoming an integral part of ALM modeling. Using machine learning for client segmentation is increasingly more common and helps in better understanding client behavior. Several machine learning techniques for (reverse) stress testing have been developed, which improve the ability to identify vulnerabilities in balance sheets. Furthermore, predictive analytics helps to optimize balance sheet management, empowering banks to make informed strategic decisions.

Capital and Performance

Final critical elements of strategically steering a bank are the management of capital and performance measurement. Capital management is a fundamental part of modern-day banking and one of the important factors in balance sheet management. Mishandling capital requirements can significantly impact competitiveness and distort the view of risk-adjusted performance. To manage capital effectively, banks need to identify the ex-ante cost of capital for each transaction and incorporate it into pricing. Capital requirements should be allocated at the transaction level, allowing for accurate calculation of capital usage per portfolio. Ongoing capital monitoring and alignment to stress testing exercises and risk appetite is essential for optimal capital allocation and planning.

An effective Funds Transfer Pricing (FTP) framework is essential to assess risk-adjusted performance at the transaction level and to allocate overall performance across business units. In a mature FTP framework, all products are priced using an internally determined FTP curve. At a minimum, this curve needs to reflect the interest rate and liquidity risks inherent to transactions, but it can be extended to incorporate other types of risk. The FTP curve must be dynamic, adapting to portfolios and market conditions. Moreover, the FTP curve should be governed by senior management, who adjust it as needed to steer the balance sheet through (dis)incentivizing specific products or maturities.

Figure 5: Usage and granularity of FTP frameworks, based on a survey performed by Zanders.

Conclusion

The key to successfully managing banking book risks is an effective ALM framework. By leveraging your ALM framework and ensuring it aligns with the bank’s overall strategy, business objectives and complexity, you can enhance treasury’s performance and effectively manage the increased regulatory attention to IRRBB strategies.

At Zanders, we developed a model to assess the maturity level of a bank’s ALM framework. The model provides valuable insights into the maturity of the individual components and the ALM framework as a whole. This facilitates quick and straightforward benchmarking.

We invite you to complete the survey below and participate in the benchmarking exercise, which should take you less than 10 minutes. We will analyze your answers and share the (anonymized) findings with you.

ALM framework benchmarking survey

Please contact Erik Vijlbrief or Jelle Thijssen for more information.

The EBA is proposing key changes to its definition of default guidelines, with implications for credit risk practices.

On July 2nd, the European Banking Authority (EBA) published a Consultation Paper proposing amendments to its 2016 Guidelines on the application of the definition of default (DoD). As part of the consultation process, open until 15 October 2025, the credit risk specialists at Zanders will submit a formal response, leveraging our extensive experience in DoD regulation and implementation.

In this article, we share our perspective on three of the EBA’s proposed amendments, focusing on the potential impact and implementation challenges for institutions:

- We expect that a shorter probation period for forbearance measures (that only alter the repayment schedule leading to a NPV loss not greater than 5%) are expected to provide incentives for banks to opt for those types of measures rather than the most sustainable ones.

- We recommend the EBA to implement EU wide DoD guidelines they considered for payment moratoria (similar to the one for Covid), whereas the EBA proposes not to. Zanders would approve permanent moratoria guidelines, as it clarifies if governmental moratoria introduced for climate risk related natural disasters should be regarded as forbearance.

- We are oncerned that the proposal to consider material arrears on non-recourse factoring exposures up to 90 (instead of 30) DPD as technical past due situations could result in an undesired increase in the percentage of IFRS stage 1 exposures migrating directly to stage 3 (impairment).

The following chapters elaborate on these three proposed amendments in more detail.

Forbearance

The first amendments addressed in the EBA’s consultation paper (CP) are related to forbearance. The supervisory authority explains that an increase of 1% threshold for a diminished financial obligation (DFO) to 5% was considered for certain forbearance measures. This follows from the European Commission’s mandate that the update of the EBA guidelines on DoD“… shall take due account of the necessity to encourage institutions to engage in proactive, preventive and meaningful debt restructuring to support obligors.”1

In the EBA’s current DoD guidelines (DoD GL), a forbearance measure leading to a 1% or more DFO results in a default classification, which could discourage institutions from applying these measures. However, the CP purposefully proposes to exclude an increase to a 5% DFO threshold, since institutions can already implement strict(er) forbearance definitions (i.e. for concession, financial difficulty) to prevent undue default classifications. Instead, the EBA proposes to shorten the probation period from 12 to 3 months for forbearance measures that: (1) only lead to suspensions or postponements and not e.g. changes to the interest rate or exposure amounts and (2) leading to less than 5% DFO loss.

This treatment will likely incentivize institutions to choose forbearance measures in scope of the shorter probation period, rather than the ones that would be optimal for a “sustainable performing repayment status” of the obligor. The latter would be in line with the EBA’s own requirements on the management of forborne exposures (Par. 125 EBA/GL/2018/06). Furthermore, the fact that the EBA does not set the “predefined limited period of time” for the measures in scope could lead to RWA variability, as some institutions may apply the shorter probation period to longer duration forbearance measures than others. For example, if Bank A sets the limited period of time to 6 months, they can apply the shorter probation period more often compared to Bank B, which sets the period of time at 3 months. Finally, it appears as if the proposal of the banking authority aims at favouring granting forbearance measures in scope to obligors with short-term (rather than structural) financial difficulties. That is, the EBA explains that the forbearance measures in scope of the shorter probation period treatment “… would most likely be viable for obligors in temporary financial difficulties”. The shorter probation period would then lead to a return to a performing status earlier for obligors to which the forbearance measures in scope are extended, which leads to a better RWA for these obligors. Alternatively, a distinct probation period (or even higher DFO threshold) could be proposed for obligors in short-term financial difficulties, as defined in Paragraph 129(A) of the EBA’s guidelines on Management of Forborne Exposures. This would also achieve the EBA’s goal, without influencing institutions’ decision about which forbearance measure to apply.

It should be mentioned that while a large RWA impact is not anticipated from the establishment of a distinct probation period, there will likely be a significant implementation burden associated with the change. This is because, as multiple forbearance measures are usually adopted in tandem, different probation periods must be traced concurrently. The implementation of this modification would need to be retroactive, though, as credit risk models will need to be recalculated using adjusted historical data in order to account for this change. In the past, retroactively modifying the probationary period has proven to be a time-consuming and expensive problem.

Legislative payment moratoria

In light of the COVID-19 crisis, the EBA published guidelines in 2020 on handling payment moratoria introduced by governments as a means of financial aid in the context of forbearance. For certain COVID-19 measures allowing e.g. a grace period in scope of the guidelines, EBA/GL/2020/02 and amendments in .../08 and …/15, would not in itself require institutions to classify the exposures as forborne.

Even though the EBA considered introducing guidelines for potential future moratoria, the CP proposes against these changes. As one of the arguments against new moratoria guidelines, the EBA remarks that moratoria in itself will not result in DFO loss of more than 1%, hence not leading to defaults. The EBA implies that introducing new moratoria guidelines would therefore be obsolete. The EBA is also worried about RWA variability that might arise if governments declare legislative moratoria for crises in their jurisdictions. That is, the EBA expects that intra-EU comparability of RWA across institutions, might be compromised.

Adding the considered guidelines describing when moratoria should lead to forbearance in the amended DoD GL is advisable, even though the EBA proposes in the CP to remove them. Zanders challenges that guidelines describing when moratoria do not lead to forbearance would not be necessary, because the 1% DFO threshold will not be met. That is, Zanders highlights moratoria guidelines would still decide when the forborne status should be assigned to exposures if moratoria are applied. This forborne status impacts the default status later on, both for performing and defaulted exposures. The reason is that if performing forborne exposures become 30 days past due within 24 months after receiving the forborne status, a defaulted status should be assigned. If the moratoria do not lead to a forborne status, these exposures should default after becoming 90 days past due on a material amount instead. Furthermore, for defaulted exposures, it is important to understand when moratoria result in the forborne status and when they do not. That is, in order for a forborne defaulted exposure to go out of default, a substantial payment and an extended cure period are needed. Zanders would therefore be in favor of EBA guidelines that specify when moratoria should result in a forborne status and when this is not necessary.

As for the RWA variability, as self-identified by the EBA, stringent criteria could be introduced prescribing what moratoria are in scope of the amended DoD GL. As described by the EBA as well, in light of climate risk related natural disasters, payment moratoria could occur more often as a governmental means of financial aid. In contrast to ad hoc rules for each specific crisis, such as observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Zanders contends that permanently applicable moratoria instructions in the updated DoD GL will eventually lead to a more stable RWA impact when economic or natural catastrophes occur.

Days past due for non-recourse factoring

Paragraph 23(D) of the current version of the DoD guideline stipulates that in the specific situation of non-recourse factoring for which the arrears materiality threshold is breached, but none of the receivables is more than 30 days past due (DPD), should be treated as a technical past due situation. Non-recourse factoring refers to the situation where the institution (e.g. a bank) has bought receivables from its client (e.g. service provider) owed by the debtor (e.g. service consumer). The idea behind the 30 DPD is that the DPD counter might continue to increase due to a consecutive overlap in non-payments of invoices, lengthy administrative processes, and a low degree of control of the institution over the invoices.

The CP proposes to allow for up to 90 DPD to be considered technical past due situations, in correspondence to the industry requesting the EBA to be more lenient in the DoD guidelines for non-recourse factoring. This is motivated by the fact that many corporates have at least one invoice past due more than 30 days, while being rated investment grade.

Although Zanders understands corporates’ need for more leniency, allowing for up to 90 DPD to be recognized as technical past due could make stage 2 obsolete for IFRS provisioning models. That is, if material arrears on non-recourse factoring exposures should be considered technical past due for situations up to 90 DPD, the said exposures will move from 0 DPD to 91 DPD in one day. The additional lenience would break the desired flow of exposures transitioning from IFRS stage 1 (performing), first towards stage 2 (significant increase in credit risk), before going to stage 3 (credit impaired). This stage migration effect could be mitigated by another stage 2 trigger: forbearance. However, the institution cannot apply forbearance measures to a sold invoice that is due to the institution’s client, rather than due to the institution itself. Therefore, as a stage 2 trigger, forbearance cannot compensate for the lack of the30 DPD in the particular scenario of non-recourse factoring risks.

Zanders proposes to find a balance between leniency on DoD guidelines and stage migrations, by increasing the 30 days threshold. The proposed number of days should be based on an analysis of non-recourse factoring portfolios from a representative sample of supervised institutions. This analysis should then strike a balance between the average observed days past due of invoices sold on the one hand and the representativeness of IFRS stage transitions on the other hand. Zanders is convinced that amending DoD GL based on this analysis will prevent the undesired impact on IFRS provisioning models and will better fit European corporate invoicing practice.

Conclusion

In this post we analysed 3 proposed amendments from the published Consultation Paper, in which the European Banking Authority (EBA) proposes amendments to its 2016 Guidelines on the application of the definition of default (DoD). Alternatives are suggested for all 3 proposed amendments as the proposed amendments leave room for improvements .

Reach out to our experts John de Kroon and Dick de Heus, if you are interested in getting a better understanding of what the proposed amendments mean for your credit risk portfolio.

We monitor the progress of the Consultation Paper in the future. Keep a close eye on our LinkedIn and website for more information, or subscribe to our newsletters here.

Citations

- Article 178(7) CRR as amended by Regulation (EU) 2024/1623 (CRR3). ↩︎

As FRTB tightens the screws on capital requirements, banks must get smart about capital attribution.

Industry surveys show that FRTB may lead to a 60% increase in regulatory market risk capital requirements, placing significant pressure on banks. As regulatory market risk capital requirements rise, it is imperative that banks employ robust techniques to effectively understand and manage the drivers of capital. However, isolating these drivers can be challenging and time-consuming, often relying on inefficient and manual techniques. Capital attribution techniques provide banks with a solution by automating the analysis and understanding of capital drivers, enhancing their efficiency and effectiveness in managing capital requirements.

In this article, we share our insights on capital attribution techniques and use a simulated example to compare the performance of several approaches.

The benefits of capital attribution

FRTB capital calculations require large amounts of data which can be difficult to verify. Banks often use manual processes to find the drivers of the capital, which can be inefficient and inaccurate. Capital attribution provides a quantification of risk drivers, attributing how each sub-portfolio contributes to the total capital charge. The ability to quantify capital to various sub-portfolios is important for several reasons:

An overview of approaches

There are several existing capital attribution approaches that can be used. For banks to select the best approach for their individual circumstances and requirements, the following factors should be considered:

- Full Allocation: The sum of individual capital attributions should equal the total capital requirements,

- Accounts for Diversification: The interactions with other sub-portfolios should be accounted for,

- Intuitive Results: The results should be easy to understand and explain.

In Table 1, we summarize the above factors for the most common attribution methodologies and provide our insights on each methodology.

Table 1: Comparison of common capital attribution methodologies.

Comparison of approaches: A simulated example

To demonstrate the different performance characteristics of each of the allocation methodologies, we present a simulated example using three sub-portfolios and VaR as a capital measure. In this example, although each of the sub-portfolios have the same distribution of P&Ls, they have different correlations:

- Sub-portfolio B has a low positive correlation with A and a low negative correlation with C,

- Sub-portfolios A and C are negatively correlated with each other.

These correlations can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the simulated P&Ls for the three sub-portfolios.

Figure 1: Simulated P&L for the three simulated sub-portfolios: A, B and C.

The capital allocation results are shown below in Figure 2. Each approach produces an estimate for the individual sub-portfolio capital allocations and the sum of the sub-portfolio capitals. The dotted line indicates the total capital requirement for the entire portfolio.

Figure 2: Comparison of capital allocation methodologies for the three simulated sub-portfolios: A, B and C. The total capital requirement for the entire portfolio is given by the dotted line.

Zanders’ verdict

From Figure 2, we see that several results do not show this attribution profile. For the Standalone and Scaled Standalone approaches, the capital is attributed approximately equally between the sub-portfolios. The Marginal and Scaled Marginal approaches include some estimates with negative capital attribution. In some cases, we also see that the estimate for the sum of the capital attributions does not equal the portfolio capital.

The Shapley method is the only method that attributes capital exactly as expected. The Euler method also generates results that are very similar to Shapley, however, it allocates almost identical capital in sub-portfolios A and C.

In practice, the choice of methodology is dependent on the number of sub-portfolios. For a small number of sub-portfolios (e.g. attribution at the level of business areas) the Shapley method will result with the most intuitive and accurate results. For a large number of sub-portfolios (e.g. attribution at the trade level), the Shapley method may prove to be computationally expensive. As such, for FRTB calculations, we recommend using the Euler method as it is a good compromise between accuracy and cost of computation.

Conclusion

Understanding and implementing effective capital attribution methodologies is crucial for banks, particularly given the increased future capital requirements brought about by FRTB. Implementing a robust capital attribution methodology enhances a bank's overall risk management framework and supports both regulatory compliance and strategic planning. Using our simulated example, we have demonstrated that the Euler method is the most practical approach for FRTB calculations. Banks should anticipate capital attribution issues due to FRTB’s capital increases and develop reliable attribution engines to ensure future financial stability.

For banks looking to anticipate capital attribution issues and potentially mitigate FRTB’s capital increases, Zanders can help develop reliable attribution engines to ensure future financial stability. Please contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Robert Pullman (Senior Manager) for more information.

We explore the main challenges of computing Margin Value Adjustment (MVA) and share our insights on how GPU computing can be harnessed to provide solutions to these challenges.

With recent volatility in financial markets, firms need increasingly faster pre-trade and risk calculations to react swiftly to changing markets. Traditional computing methods for these calculations, however, are becoming prohibitively expensive and slow to meet the growing demand. GPU computing has recently garnered significant interest, with advances in the fields of advanced machine learning techniques and generative AI technologies, such as ChatGPT. Financial institutions are now looking at gaining an edge by using GPU computing to accelerate their high-dimensional and time-critical computing challenges.

The MVA Computing Challenge

The timely computation of MVA is essential for pre-trade and post-trade modeling of bilateral and cleared trading. Providing an accurate measure of future margin requirements over the lifetime of a trade requires the frequent revaluation of derivatives with a large volume of intensive nested Monte Carlo simulations. These simulations need to span a high-dimensional space of trades, time steps, risk factors and nested scenarios, making the calculation of MVA complex and computationally demanding. This is further complicated by the need for an increasing frequency of intra-day risk calculations, due to recent market volatility, which is pushing the limits of what can be achieved with CPU-based computing.

An Introduction to GPU Computing

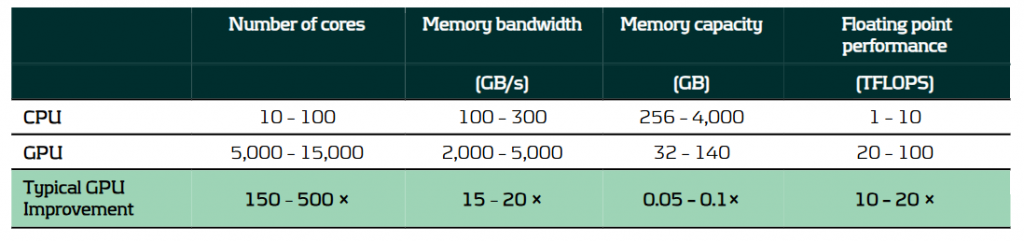

GPU computing utilizes graphics processing units, which are specifically designed to handle large volumes of parallel calculations. This capability makes them ideal for solving programming challenges that benefit from high levels of parallelization and data throughput. Consequently, GPUs can offer substantial benefits over traditional CPU-based computing, thanks to their architectural differences, as outlined in the table below.

A comparison of the typical capabilities of enterprise-level hardware for CPUs and GPUs.

It is because of these architectural differences that CPUs and GPUs excel in different areas:

- CPUs feature fewer but more powerful cores, optimized for general-purpose computing with complex, branching instructions. They excel in performing serial calculations with high single-core performance.

- GPUs consist of a large number of less powerful cores and with higher memory bandwidth. This makes them ideal for handling large volumes of parallel calculations with high throughput.

Solving the MVA Computational Challenge with GPU Computing

The requirement to calculate large volumes of granular simulations makes GPU computing especially well-suited to solving the MVA computational challenge. The use of GPU computing can lead to significant improvements in performance for not only MVA but a range of problems in finance, where it is not uncommon to see improvements in calculation speed of 10 – 100x. This performance increase can be harnessed in several ways:

- Speed: The high throughput of GPUs provides results more quickly, providing faster risk calculations and insights for decision-making, which is particularly important for pre-trade calculations.

- Throughput: GPUs can more quickly and efficiently process large calculation volumes, providing institutions with more peak computing bandwidth, reducing workloads on CPU-grids that can be used for other tasks.

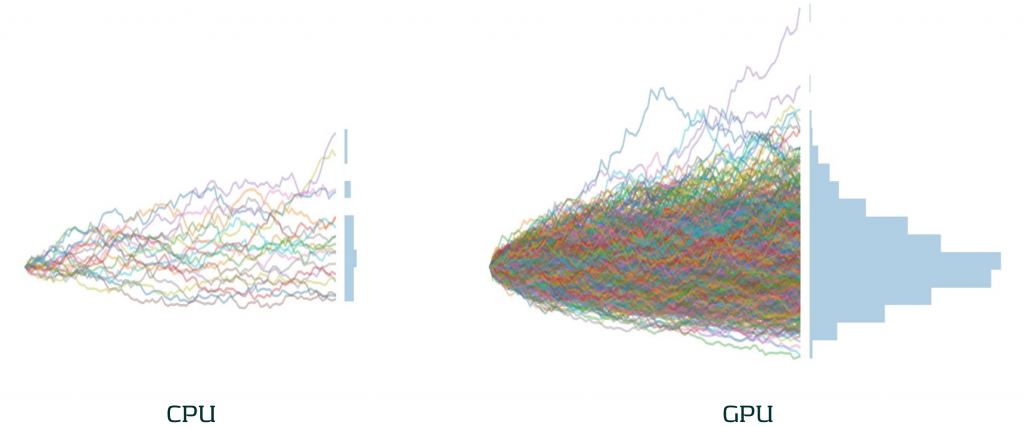

- Accuracy: With greater parallel processing capabilities, the accuracy of models can be improved by using more sophisticated algorithms, greater granularity and a larger number of simulations. As illustrated below, the difference in the number of Monte Carlo simulations that can be achieved by GPUs in the same time as CPUs can be significant.

The difference in the number of Monte Carlo paths than can be simulated in the same time between an equivalent enterprise-level CPU and GPU.

Case Study: Our approach to accelerating MVA with GPUs

To illustrate the impact of GPU computing in a real situation, we present a case study of our work accelerating MVA calculations for a major bank.

Challenge: A large investment bank was seeking to improve the performance of their pre-trade MVA for more timely calculations. This was challenging as they needed to compute their MVA exposures over long time horizons, with a large number of paths. Even with a sensitivity-based approach, this process took close to 10 minutes using a single-threaded CPU calculation.

Solution: Zanders analyzed the solution and identified several bottlenecks. We developed and optimized a GPU-accelerated solution to ensure efficient GPU utilization, parallelizing the calculations across scenarios and risk factors.

Performance: Our GPU implementation improved MVA calculation speed by 51x. Improving calculation time from just under 10 minutes to 10 seconds. This significant increase in speed enabled more timely and frequent assessments and decisions on MVA.

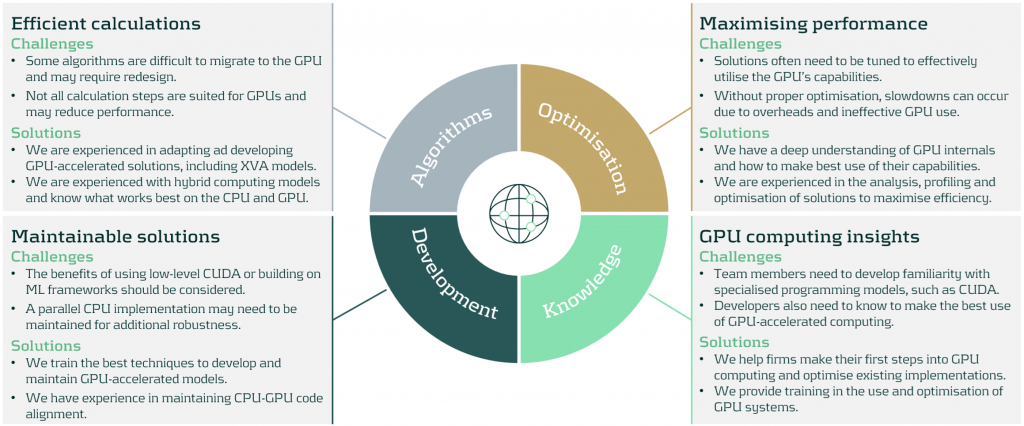

Our Recommendation: A strategic approach to GPU computing implementations

There are significant benefits to be achieved with the use GPU computing. However, there are some considerations to ensure an effective use of resources:

We work with firms to develop bespoke solutions to meet their high-performance computing needs. Zanders can help in all aspects of GPU computing implementation, from initial design to the analysis, development and optimization of your GPU computing implementation.

Conclusion

GPU computing offers significant improvements in the speed and efficiency of financial calculations, typically boosting calculation speeds by factors of 10-100x. This enables financial institutions to manage their risk more effectively, including the computationally demanding calculations of MVA. By replacing CPU-based calculations with GPU computing, banks can dramatically improve their capacity to process greater volumes of calculations with higher frequency. As financial markets continue to evolve, GPU computing will play an increasingly vital role in their calculation infrastructure.

To find out more on how GPU computing can enhance your institution's risk management processes, please contact Steven van Haren (Director) or Mark Baber (Senior Manager).

Asset liability management (ALM) is an important part of banking at any time, but it tends to come more sharply into focus during times of interest rate instability. This is certainly the case in recent years.

After a prolonged period of stable low (and at points even negative) interest rates, 2022 saw the return of rising rates, prompting Dutch digital bank, Knab, to appoint Zanders to reevaluate and reinforce the bank’s approach to risk.

The evolution of Knab

Founded in 2012 as the first fully digital bank in The Netherlands, Knab offers a suite of online banking products and services to support entrepreneurs both in their business and private needs.

“It's an underserved client group,” says Tom van Zalen, Knab’s Chief Risk Officer. “It's a nice niche as there is a strong need for a bank that really is there for these customers. We want to offer products and services that are really tailored to the specific needs of those entrepreneurs that often don’t fit the standard profile used in the market.”

Over time, the bank’s portfolio has evolved to offer a broad suite of online banking and financial services, including business accounts, mortgages, accounting tools, pensions and insurance. However, it was Knab’s mortgage portfolio that led them to be exposed to heightened interest rate risk. Mortgages with relatively long maturities command a large proportion of Knab’s balance sheet. When interest rates started to rise in 2022, increasing uncertainty in prepayments posed a significant risk to the bank. This emphasized the importance of upgrading their risk models to allow them to quantify the impact of changes in interest rates more accurately.

“With mortgages running for 20 plus years, that brings a certain interest rate risk,” says Tom. “That risk was quite well in control, until in 2022 interest rates started to change a lot. It became clear the risk models we were using needed to evolve and improve to align with the big changes we were observing in the interest rate environment—this was a very big thing we had to solve.”

In addition, in the background at around this time, major changes were happening in the ownership of the bank. This ultimately led to the sale of Knab (as part of Aegon NL) to a.s.r. in October 2022 and then to Bawag in February 2024. Although these transactions were not linked to the project we’re discussing here, they are relevant context as they represent the scale of change the bank was managing throughout this period, which added extra layers of complexity (and urgency) to the project.

A team effort

In 2022, Zanders was appointed by Knab to develop an Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB) Roadmap that would enable them to navigate the changes in the interest rate environment, ensure regulatory compliance across their product portfolio and generally provide them with more control and clarity over their ALM position. As a first stage of the project, Zanders worked closely with the Knab team to enhance the measurement of interest rate risk. The next stage of the project was then to develop and implement a new IRRBB strategy to manage and hedge interest rate risk more comprehensively and proactively by optimizing value risk, earnings risk and P&L.

“The whole model landscape had to be redeveloped and that was a cumbersome and extensive process,” says Tom. “Redevelopment and validation took us seven to eight months. If you compare this to other banks, that sort of execution power is really impressive.”

The swiftness of the execution is the result of the high priority awarded to the project by the bank combined with the expertise of the Zanders team.

Zanders brings a very special combination of experts. Not only are they able to challenge the content and make sure we make the right choices, but they also bring in a market practice view. This combination was critical to the success of the execution of this project.

Tom van Zalen, Knab’s Chief Risk Officer.

Clarity and control

Armed with the new IRRBB infrastructure developed together with Zanders, the bank can now measure and monitor the interest rate risks in their product portfolio (and the impact on their balance sheet) more efficiently and with increased accuracy. This has empowered Knab with more control and clarity on their exposure to interest rate risk, enabling them to put the right measures in place to mitigate and manage risk effectively and compliantly.

“The model upgrade has helped us to reliably measure, monitor and quantify the risks in the balance sheet,” says Tom. “With these new models, the risk that we measure is now a real reflection of the actual risk. This has helped us also to rethink our approach on managing risk.”

The success of the project was qualified by an on-site inspection by the Dutch regulator, De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), in April 2024. With Zanders supporting them, the Knab team successfully complied with regulatory requirements, and they were also complimented on the quality of their risk organization and management by the on-site inspection team.

Lasting impact

The success of the IRRBB Roadmap and the DNB inspection have really emphasized the extent of changes the project has driven across the bank’s processes. This was more than modeling risk, it was about embedding a more calculated and considered approach to risk management into the workings of the bank.

“It was not just a consultant flying in, doing their work and leaving again, it was really improving the bank,” says Tom. “If we look at where we are now, I really can say that we are in control of the risk, in the sense that we know where it is, we can measure it, we know what we need to do to manage it. And that is, a very nice position to be in.”

For more information on how Zanders can help you enhance your approach to interest rate risk, contact Erik Vijlbrief.

Following the publication of its focus areas for IRRBB in 2024 and 2025, the European Banking Association (EBA) has now published an update regarding the implementation and explains the next steps.

The implementation update covers observations, recommendations and supervisory tools to enhance the assessment of IRRBB risks for institutions and supervisors.1 Main topics include non-maturing deposit (NMD) behavioral assumptions, complementary dimensions to the SOT NII, the modeling of commercial margins for NMDs in the SOT NII, as well as hedging strategies.

Some key highlights and takeaways from the results of sample institutions as per Q4 2023:

- Large dispersion across behavioral assumptions on NMDs is observed. The significant volume of NMDs as part of EU banks’ balance sheets, differences in behavior between customer / product groups and developments in deposit volume distributions, however, underline the need for more solid and aligned modeling. The EBA hence suggests NMD modeling enhancements and recommends (1) banks to consider various risk factors related to the customer, institution and market profile, as well as (2) a supervisory toolkit to monitor parameters / risk factors. Segmentation and peer benchmarking, (reverse) stress testing as well as (combining) expert judgment and historical data are paramount in this regard. The recommendations spark banks to reevaluate forward looking approaches, as shifting deposit dynamics render calibration solely based on historical data insufficient. Establishing a thorough expert judgment governance including backtesting is vital in this respect. Moreover, assessing and substantiating how a bank’s modeling relates to the market is more important than ever.

- Next to the NII SOT that serves as a metric to flag outlier institutions from an NII perspective, the EBA proposes additional dimensions to be considered by supervisors. These dimensions, which aim to reflect internal NII metrics, must complement the assessment and enhance the understanding of IRRBB exposures and management. The proposed dimensions include (1) market value changes of fair value instruments, (2) interest rate sensitive fees/commissions & overhead costs, and (3) interest rate related embedded losses and gains. It is important to note that it is not intended to introduce new limits or thresholds associated with these dimensions.

- Given concerns and dispersion regarding the modeling of commercial margins for NMDs in the NII SOT (38% of sample institutions assumed constant commercial margins versus the remainder not applying constant margins), the EBA now provided additional guidance on the expected approach. They recommend institutions to align the assumptions with those in their internal systems, or apply a constant spread over the risk-free rate when not available. Key considerations include the current spread environment, the context of zero or negative interest rates and lags in pass-through. The EBA’s clarification indicates that banks are allowed to apply a non-constant spread. This serves as an opportunity for banks still applying constant ones, as using non-constant spreads enhances the ability to quantify NII risk under an altering interest rate environment.

- Hedging practices vary significantly across institutions, although hedging instruments (i.e. interest rate swaps) to manage open IRRBB positions are aligned. Hedging strategies have significantly contributed to meeting regulatory requirements, with all institutions meeting the SOT EVE as per Q4 2023, compared to 42% that would not have complied if hedges were disregarded. For the SOT NII, however, 13% of the sample institutions would have been considered outliers if this regulatory measure had been applied in Q4 2023 (versus 21% when disregarding hedges). This result shows that it is key for banks to find a balance between value and earnings stability, and apply hedging strategies accordingly. As compliance with SOTs must be ensured under all circumstances, stressed client behavior and market dynamics must be accounted for.

In the upcoming years, the EBA will continue monitoring the impact of the IRRBB regulatory package, focusing on NMD modeling, hedging strategies, and potential scope extensions to commercial margin modeling. It will also assess Pillar 3 disclosure practices and track key regulatory elements such as the 5-year cap on NMD repricing maturity and Credit Spread Risk in the Banking Book (CSRBB)-related aspects. Additionally, the EBA will contribute to the International Accounting Standards Board’s (IASB's) Dynamic Risk Management (DRM) project and evaluate the impact of recalibrated shock scenarios from the Basel Committee.

The EBA publication triggers banks to take action on the four topics outlined above, as well as on hedge accounting (DRM) in the near future. Zanders has extensive relevant experience, and supported on:

- Numerous NMD topics, including modeling, validation and benchmarking. Furthermore, we published a series of whitepapers regarding NMD modeling concepts and approaches, deposit rate dynamics, forward looking perspectives and migration dynamics in deposits that is particularly relevant following this EBA publication.

- Drafting an IRRBB strategy, advising on coupon stripping and developing a hedging strategy, thereby carefully balancing value and NII risks (SOT EVE / NII).

- Validating a hedge accounting framework, developing a hedge account model and hedge accounting outsourcing. Zanders moreover held a survey on DRM as well as published an extensive series of articles on the DRM project of the IASB and its implications for banks.

Contact Jaap Karelse, Erik Vijlbrief (Netherlands, Belgium and Nordic countries) or Martijn Wycisk (DACH region) for more information.

Citations

This article delves into a three-step approach to portfolio optimization by harnessing the power of advanced data analytics and state-of-the-art quantitative models and tools.

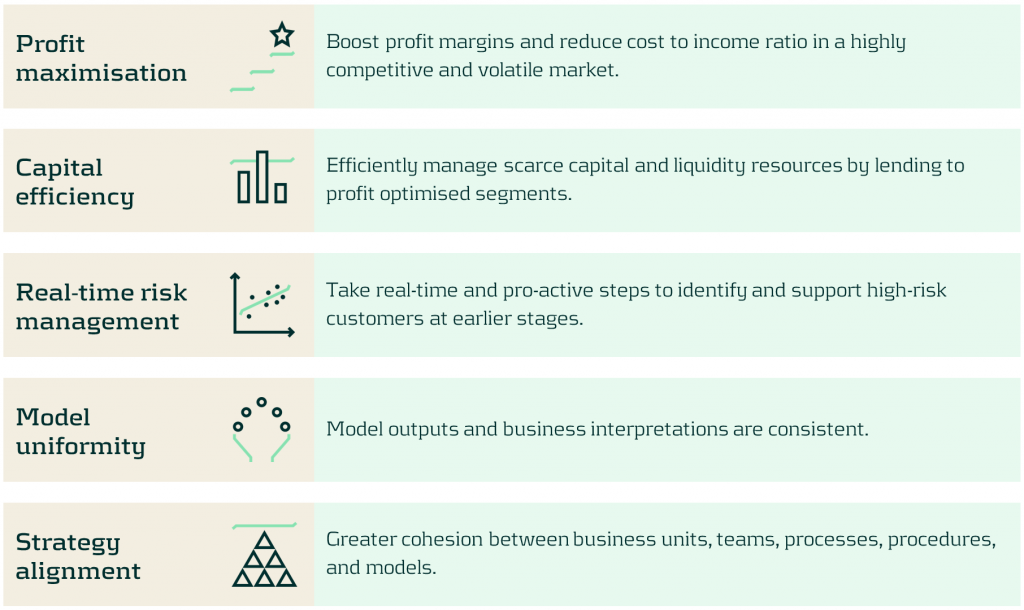

In today's dynamic economic landscape, optimizing portfolio composition to fortify against challenges such as inflation, slower growth, and geopolitical tensions is ever more paramount. These factors can significantly influence consumer behavior and impact loan performance. Navigating this uncertain environment demands banks adeptly strike a delicate balance between managing credit risk and profitability.

Why does managing your risk reward matter?

Quantitative techniques are an essential tool to effectively optimize your portfolio’s risk reward profile, as this aspect is often based on inefficient approaches.

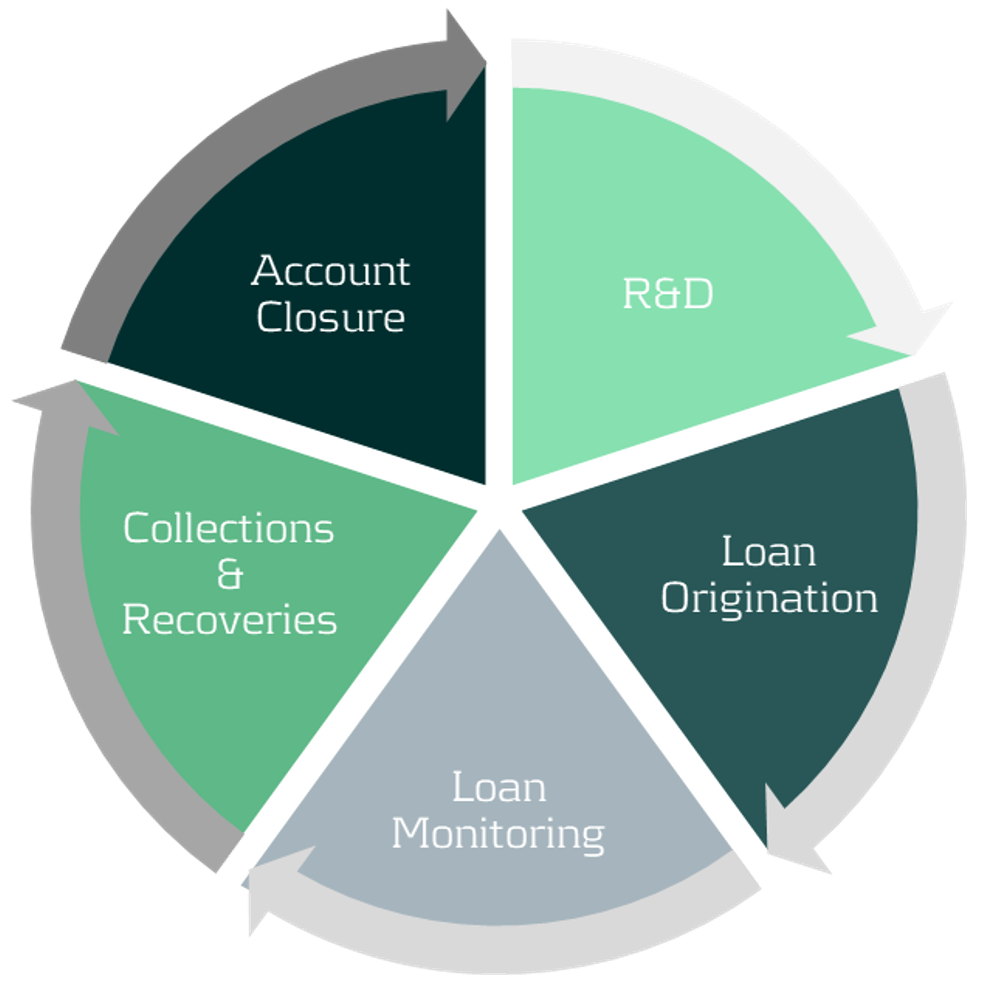

Existing models and procedures across the credit lifecycle, especially those relating to loan origination and account management, may not be optimized to accommodate current macro-economic challenges.

Figure 1: Credit lifecycle.

Current challenges facing banks

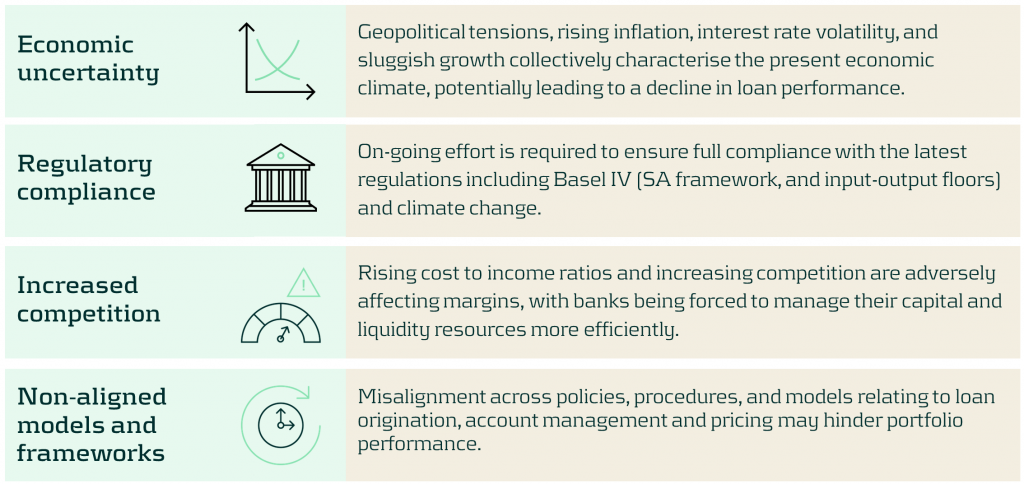

Some of the key challenges banks face when balancing credit risk and profitability include:

Our approach to optimizing your risk reward profile

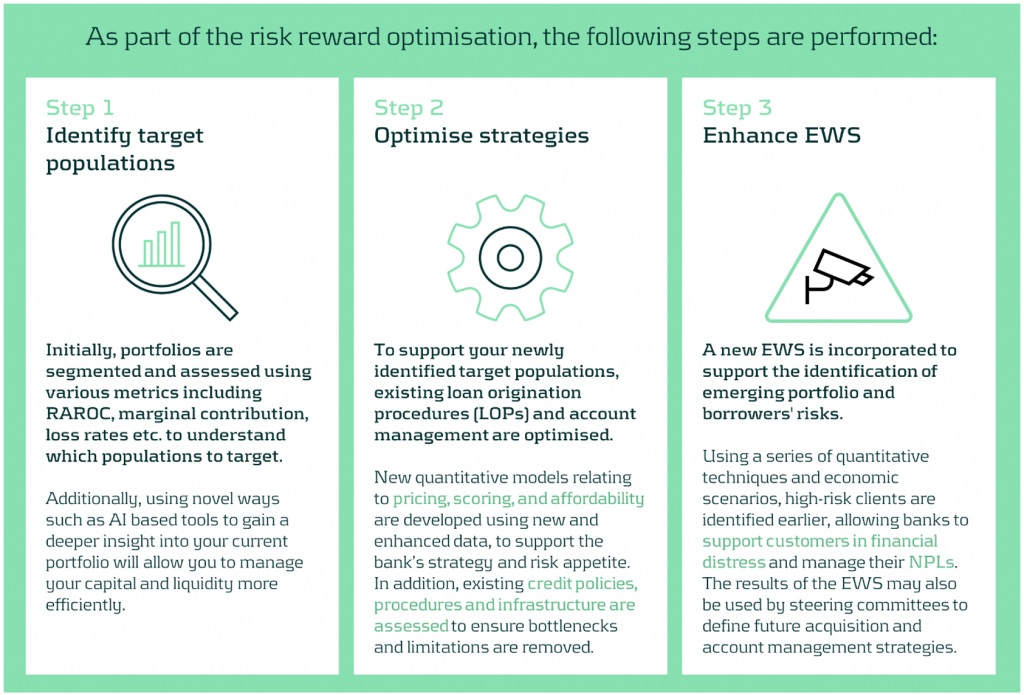

Our optimization approach consists of a holistic three step diagnosis of your current practices, to support your strategy and encourage alignment across business units and processes.

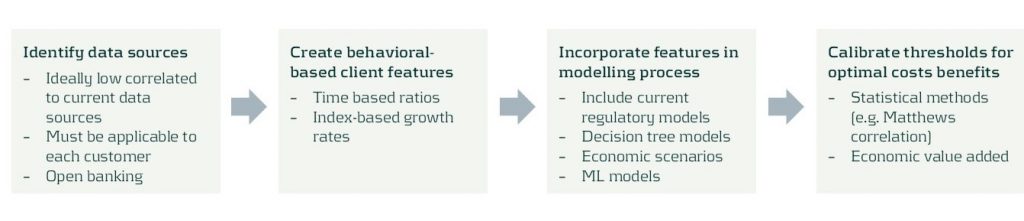

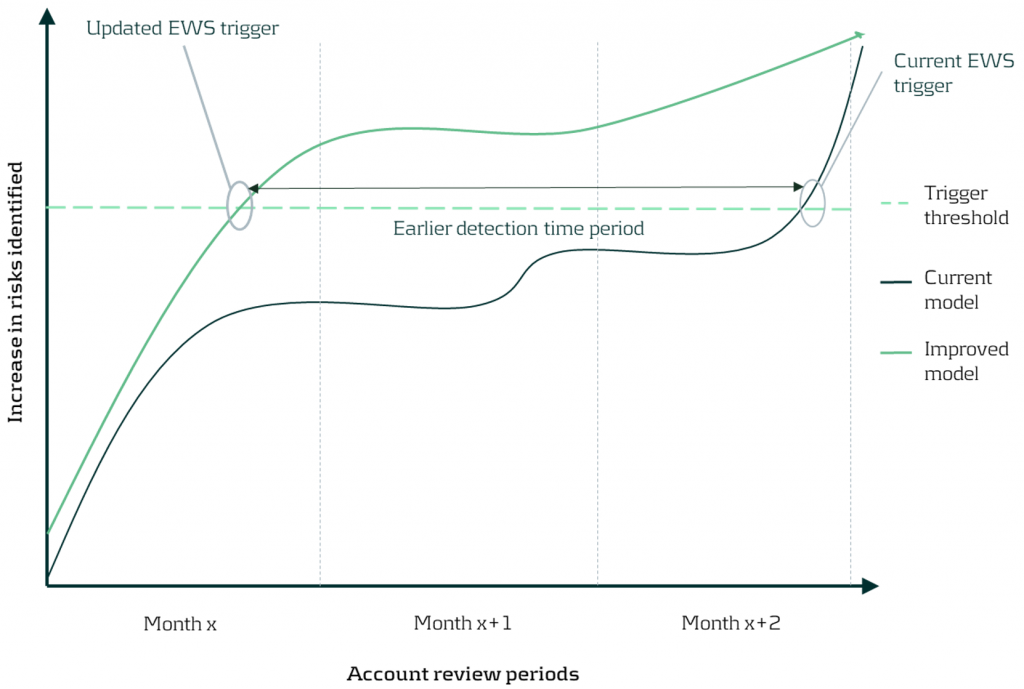

The initial step of the process involves understanding your current portfolio(s) by using a variety of segmentation methodologies and metrics. The second step implements the necessary changes once your primary target populations have been identified. This may include reassessing your models and strategies across the loan origination and account management processes. Finally, a new state-of-the-art Early Warning System (EWS) can be deployed to identify emerging risks and take pro-active action where necessary.

A closer look at redefining your target populations

With the proliferation of advanced data analytics, banks are now better positioned to identify profitable, low-risk segments. Machine Learning (ML) methodologies such as k-means clustering, neural networks, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) enable effective customer grouping, behavior forecasting, and market sentiment analysis.

Risk-based pricing remains critical for acquisition strategies, assessing segment sensitivity to different pricing strategies, to maximize revenue and reduce credit losses.

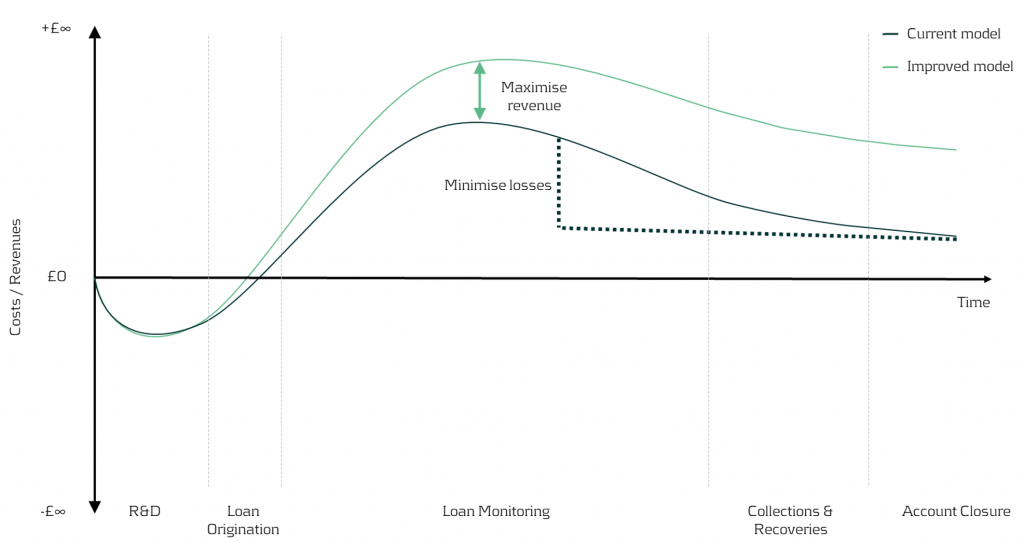

Figure 2: In the illustration above, we can visually see the impact on earnings throughout the credit lifecycle driven by redefining the target populations and application of different pricing strategies.

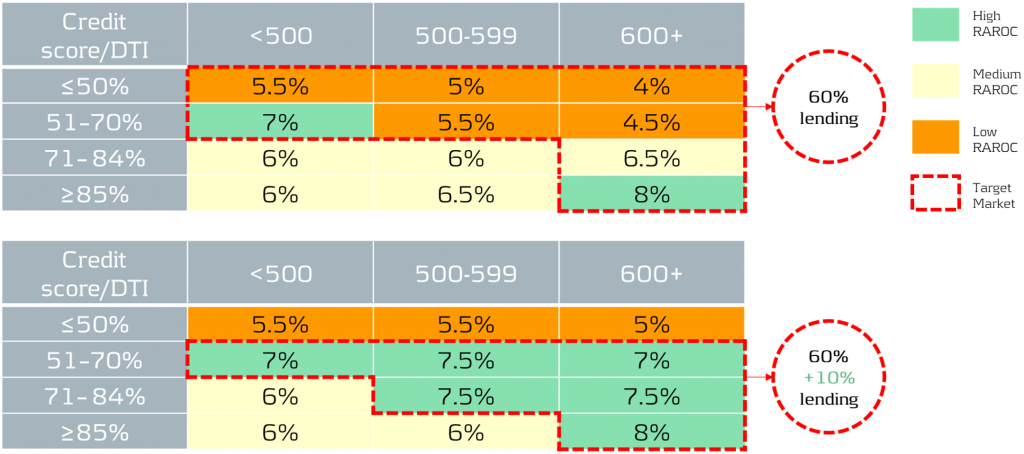

In our simplified example, based on the RAROC metric applied to an unsecured loans portfolio, we take a 2-step approach:

1- Identify target populations by comparing RAROC across different combinations of credit scores and debt-to-income (DTI) ratios. This helps identify the most capital efficient segments to target.

2- Assess the sensitivity of RAROC to different pricing strategies to find the optimal price points to maximize profit over a select period - in this scenario we use a 5-year time horizon.

Figure 3: The top table showcases the current portfolio mix and performance, while the bottom table illustrates the effects of adjusting the pricing and acquisition strategy. By redefining the target populations and changing the pricing strategy, it is possible to reallocate capital to the most profitable segments whilst maintaining within credit risk appetite. For example, 60% of current lending is towards a mix of low to high RAROC segments, but under the new proposed strategy, 70% of total capital is allocated to the highest RAROC segments.

Uncovering risks and seizing opportunities

The current state of Early Warning Systems

Many organizations rely on regulatory models and standard risk triggers (e.g., no. of customers 30 day past due, NPL ratio etc.) to set their EWS thresholds. Whilst this may be a good starting point, traditional models and tools often miss timely deteriorations and valuable opportunities, as they typically use limited and/or outdated data features.

Target state of Early Warning Systems

Leveraging timely and relevant data, combined with next-generation AI and machine learning techniques, enables early identification of customer deterioration, resulting in prompt intervention and significantly lower impairment costs and NPL ratios.

Furthermore, an effective EWS framework empowers your organization to spot new growth areas, capitalize on cross-selling opportunities, and enhance existing strategies, driving significant benefits to your P&L.

Figure 4: By updating the early warning triggers using new timely data and advanced techniques, detection of customer deterioration can be greatly improved enabling firms to proactively support clients and enhance the firm’s financial position.

Discover the benefits of optimizing your portfolios

Discover the benefits in optimizing your portfolios’ risk-reward profile using our comprehensive approach as we turn today’s challenges into tomorrow’s advantages. Such benefits include:

Conclusion

In today's rapidly evolving market, the need for sophisticated credit risk portfolio management is ever more critical. With our comprehensive approach, banks are empowered to not merely weather economic uncertainties, but to thrive within them by striking the optimal risk-reward balance. Through leveraging advanced data analytics and deploying quantitative tools and models, we help institutions strategically position themselves for sustainable growth, and comply with increasing regulatory demands especially with the advent of Basel IV. Contact us to turn today’s challenges into tomorrow’s opportunities.

For more information on this topic, contact Martijn de Groot (Partner) or Paolo Vareschi (Director).

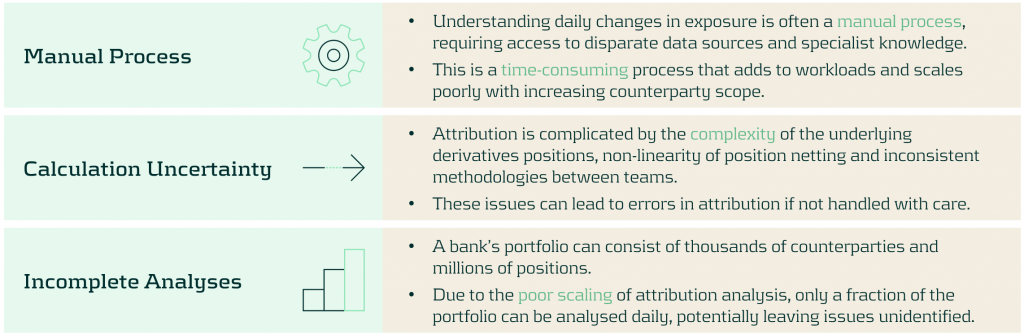

In an increasingly complex regulatory landscape, effective management of counterparty credit risk is crucial for maintaining financial stability and regulatory compliance.

Accurately attributing changes in counterparty credit exposures is essential for understanding risk profiles and making informed decisions. However, traditional approaches for exposure attribution often pose significant challenges, including labor-intensive manual processes, calculation uncertainties, and incomplete analyses.

In this article, we discuss the issues with existing exposure attribution techniques and explore Zanders’ automated approach, which reduces workloads and enhances the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the attribution.

Our approach to attributing changes in counterparty credit exposures

The attribution of daily exposure changes in counterparty credit risk often presents challenges that strain the resources of credit risk managers and quantitative analysts. To tackle this issue, Zanders has developed an attribution methodology that efficiently automates the attribution process, improving the efficiency, reactivity and coverage of exposure attribution.

Challenges in Exposure Attribution

Credit risk managers monitor the evolution of exposures over time to manage counterparty credit risk exposures against the bank’s risk appetite and limits. This frequently requires rapid analysis to attribute the changes to exposures, which presents several challenges:

Zanders’ approach: an automated approach to exposure attribution

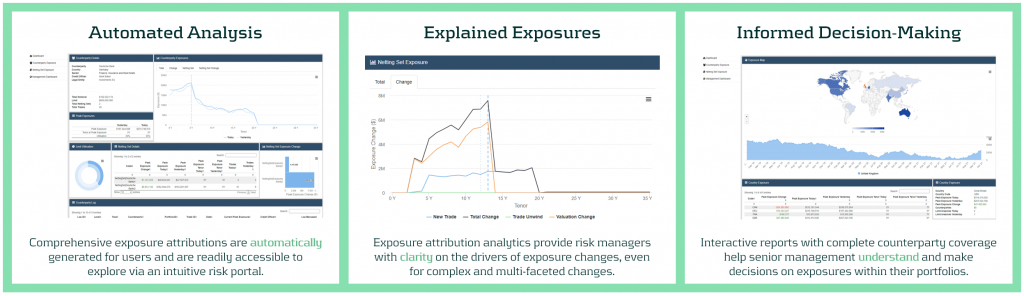

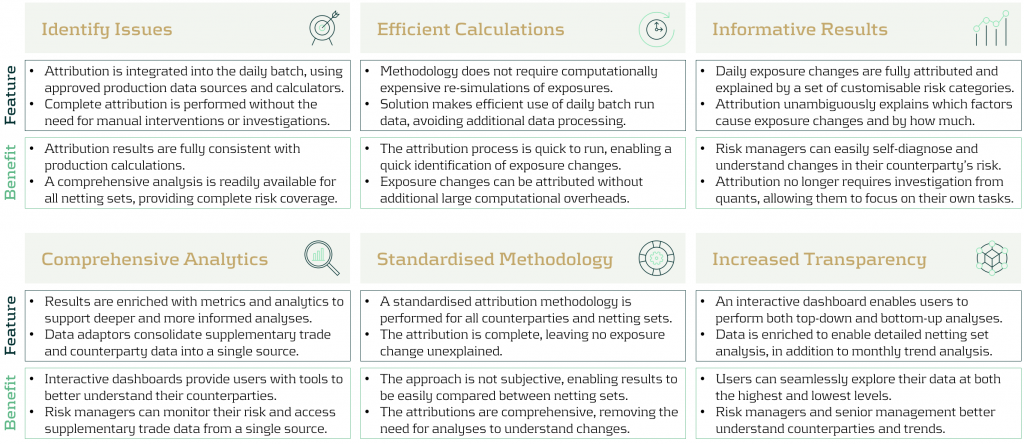

Our methodology resolves these problems with an analytics layer that interfaces with the risk engine to accelerate and automate the daily exposure attribution process. The results can also be accessed and explored via an interactive web portal, providing risk managers and senior management with the tools they need to rapidly analyze and understand their risk.

Key features and benefits of our approach

Zanders’ approach provides multiple improvements to the exposure attribution process. This reduces the workloads of key risk teams and increases risk coverage without additional overheads. Below, we describe the benefits of each of the main features of our approach.

Zanders Recommends

An automated attribution of exposures empowers banks teams to better understand and handle their counterparty credit risk. To make the best use of automated attribution techniques, Zanders recommends that banks:

- Increase risk scope: The increased efficiency of attribution should be used to provide a more comprehensive and granular coverage of the exposures of counterparties, sectors and regions.

- Reduce quant utilization: Risk managers should use automated dashboards and analytics to perform their own exposure investigations, reducing the workload of quantitative risk teams.

- Augment decision making: Risk managers should utilize dashboards and analytics to ensure they make more timely and informed decisions.

- Proactive monitoring: Automated reports and monitoring should be reviewed regularly to ensure risks are tackled in a proactive manner.

- Increase information transfer: Dashboards should be made available across teams to ensure that information is shared in a transparent, consistent and more timely manner.

Conclusion

The effective management of counterparty credit risk is a critical task for banks and financial institutions. However, the traditional approach of manual exposure attribution often results in inefficient processes, calculation uncertainties, and incomplete analyses. Zanders' innovative methodology for automating exposure attribution offers a comprehensive solution to these challenges and provides banks with a robust framework to navigate the complexities of exposure attribution. The approach is highly effective at improving the speed, coverage, and accuracy of exposure attribution, supporting risk managers and senior management to make informed and timely decisions.

For more information about how Zanders can support you with exposure attribution, please contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Mark Baber (Senior Manager).

In a world where the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) commands much attention, it’s easy for counterparty credit risk (CCR) to slip under the radar.

However, CCR remains an essential element in banking risk management, particularly as it converges with valuation adjustments. These changes reflect growing regulatory expectations, which were further amplified by recent cases such as Archegos. Furthermore, regulatory focus seems to be shifting, particularly in the U.S., away from the Internal Model Method (IMM) and toward standardised approaches. This article provides strategic insights for senior executives navigating the evolving CCR framework and its regulatory landscape.

Evolving trends in CCR and XVA

Counterparty credit risk (CCR) has evolved significantly, with banks now adopting a closely integrated approach with valuation adjustments (XVA) — particularly Credit Valuation Adjustment (CVA), Funding Valuation Adjustment (FVA), and Capital Valuation Adjustment (KVA) — to fully account for risk and costs in trade pricing. This trend towards blending XVA into CCR has been driven by the desire for more accurate pricing and capital decisions that reflect the true risk profile of the underlying instruments/ positions.

In addition, recent years have seen a marked increase in the use of collateral and initial margin as mitigants for CCR. While this approach is essential for managing credit exposures, it simultaneously shifts a portion of the risk profile into contingent market and liquidity risks, which, in turn, introduces requirements for real-time monitoring and enhanced data capabilities to capture both the credit and liquidity dimensions of CCR. Ultimately, this introduces additional risks and modeling challenges with respect to wrong way risk and clearing counterparty risk.

As banks continue to invest in advanced XVA models and supporting technologies, senior executives must ensure that systems are equipped to adapt to these new risk characteristics, as well as to meet growing regulatory scrutiny around collateral management and liquidity resilience.

The Internal Model Method (IMM) vs. SA-CCR

In terms of calculating CCR, approaches based on IMM and SA-CCR provide divergent paths. On one hand, IMM allows banks to tailor models to specific risks, potentially leading to capital efficiencies. SA-CCR, on the other hand, offers a standardised approach that’s straightforward yet conservative. Regulatory trends indicate a shift toward SA-CCR, especially in the U.S., where reliance on IMM is diminishing.

As banks shift towards SA-CCR for Regulatory capital and IMM is used increasingly for internal purposes, senior leaders might need to re-evaluate whether separate calibrations for CVA and IMM are warranted or if CVA data can inform IMM processes as well.

Regulatory focus on CCR: Real-time monitoring, stress testing, and resilience

Real-time monitoring and stress testing are taking centre stage following increased regulatory focus on resilience. Evolving guidelines, such as those from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), emphasise a need for efficiency and convergence between trading and risk management systems. This means that banks must incorporate real-time risk data and dynamic monitoring to proactively manage CCR exposures and respond to changes in a timely manner.

CVA hedging and regulatory treatment under IMM

CVA hedging aims to mitigate counterparty credit spread volatility, which affects portfolio credit risk. However, current regulations limit offsetting CVA hedges against CCR exposures under IMM. This regulatory separation of capital for CVA and CCR leads to some inefficiencies, as institutions can’t fully leverage hedges to reduce overall exposure.

Ongoing BIS discussions suggest potential reforms for recognising CVA hedges within CCR frameworks, offering a chance for more dynamic risk management. Additionally, banks are exploring CCR capital management through LGD reductions using third-party financial guarantees, potentially allowing for more efficient capital use. For executives, tracking these regulatory developments could reveal opportunities for more comprehensive and capital-efficient approaches to CCR.

Leveraging advanced analytics and data integration for CCR

Emerging technologies in data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and scenario analysis are revolutionising CCR. Real-time data analytics provide insights into counterparty exposures but typically come at significant computational costs: high-performance computing can help mitigate this, and, if coupled with AI, enable predictive modeling and early warning systems. For senior leaders, integrating data from risk, finance, and treasury can optimise CCR insights and streamline decision-making, making risk management more responsive and aligned with compliance.

By leveraging advanced analytics, banks can respond proactively to potential CCR threats, particularly in scenarios where early intervention is critical. These technologies equip executives with the tools to not only mitigate CCR but also enhance overall risk and capital management strategies.

Strategic considerations for senior executives: Capital efficiency and resilience

Balancing capital efficiency with resilience requires careful alignment of CCR and XVA frameworks with governance and strategy. To meet both regulatory requirements and competitive pressures, executives should foster collaboration across risk, finance, and treasury functions. This alignment will enhance capital allocation, pricing strategies, and overall governance structures.

For banks facing capital constraints, third-party optimisation can be a viable strategy to manage the demands of SA-CCR. Executives should also consider refining data integration and analytics capabilities to support efficient, resilient risk management that is adaptable to regulatory shifts.

Conclusion

As counterparty credit risk re-emerges as a focal point for financial institutions, its integration with XVA, and the shifting emphasis from IMM to SA-CCR, underscore the need for proactive CCR management. For senior risk executives, adapting to this complex landscape requires striking a balance between resilience and efficiency. Embracing real-time monitoring, advanced analytics, and strategic cross-functional collaboration is crucial to building CCR frameworks that withstand regulatory scrutiny and position banks competitively.

In a financial landscape that is increasingly interconnected and volatile, an agile and resilient approach to CCR will serve as a foundation for long-term stability. At Zanders, we have significant experience implementing advanced analytics for CCR. By investing in robust CCR frameworks and staying attuned to evolving regulatory expectations, senior executives can prepare their institutions for the future of CCR and beyond thereby avoiding being left behind.

On November 12 2024, the confirmed methodology for the EBA 2025 stress testing exercise was published on the EBA website. This is the final version of the draft for initial consultation that was published earlier.

| The timelines for the entire exercise have been extended to accommodate the changes in scope: | |

| Launch of exercise (macro scenarios) | Second half of January 2025 |

| First submission of results to the EBA | End of April 2025 |

| Second submission to the EBA | Early June 2025 |

| Final submission to the EBA | Early July 2025 |

| Publication of results | Beginning of August 2025 |

Below we share the most significant aspects for Credit Risk and related challenges. In the coming weeks we will share separate articles to cover areas related to Market Risk, Net Interest Income & Expenses and Operational Risk.

The final methodology, along with the requirements introduced by the CRR3 poses significant challenges on the execution of the Credit Risk stress testing. Earlier we provided details on this topic and possible impacts on stress testing results, see our article: “Implications of CRR3 for the 2025 EU-wide stress test” Regarding the EBA 2025 stress test we view the following 5 points as key areas of concern:

1- The EBA stress test requires different starting points; actual and restated CRR3 figures. This raises requirements in data management, reporting and implementation of related processes.

2- The EBA stress test requires banks to report both transitional and fully loaded results under CRR3; this requires the execution of additional calculations and implementation of supporting data processes.

3- The changes in classification of assets require targeted effort on the modeling side, stress test approach and related data structures.

4- Implementation of the Standardized Approach output floor as part of the stress test logic.

5- Additional effort is needed to correctly align Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 models, in terms of development, implementation and validation.

At Zanders, we specialize in risk advisory and our consultants have participated in every single EU wide stress testing exercise, as well as a few others going back to the initial stress tests in 2009 following the Great Financial Crisis. We can support you throughout all key stages of the stress testing exercise across all areas to ensure a successful submission of the final templates.

Based on the expertise in Stress Testing we have gained over the last 15 years, our clients benefit the most from our services in these areas:

- Full gap analysis against latest set of requirements

- Review, design and implementation of data processes & relevant data quality controls

- Alignment of Pillar 2 models to Pillar 1 (including CCR3 requirements)

- Design, implementation and execution of stress testing models

- Full automation of populating EBA templates including reconciliation and data quality checks.

Contact us for more information about how we can help make this your most successful run yet. Reach out to Martijn de Groot, Partner at Zanders.