In 2012, FrieslandCampina was given an honorable mention at the internationally renowned Adam Smith Awards for its bank relationship management. The global dairy company was recognized for its successful refinancing program. This article looks at how ‘wallet distribution’ and strategic bank relationship management allowed the company to maneuver with agility during the financial crisis.

In January 2009, Friesland Foods and Campina, the two largest dairy cooperatives in the Netherlands, merged under the name Royal FrieslandCampina N.V. and Dairy Cooperative FrieslandCampina U.A. The company’s stock is owned by nearly 20,000 members of the merged dairy cooperative – dairy farmers in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany. The company is located in 28 countries worldwide, and FrieslandCampina’s dairy products are exported, particularly from the Netherlands, to more than 100 countries.

Growing markets

Several international brands are owned by the dairy cooperative. The biggest Dutch brand, Campina, is the cooperative’s fifth-largest brand. FrieslandCampina’s impressive turnover and growth is particularly noticeable in Asia and Africa. The biggest brands in these continents are Frisian Flag in Indonesia, followed by Peak in Nigeria, Dutch Lady in Vietnam and Malaysia, and Friso – the fastest-growing brand – which is sold in China, Malaysia, and Vietnam, as well as other countries. Next to Peak, the Friso brand recently started selling baby and children’s food in Nigeria, where the number of babies born equals the total in Europe, making it an extremely attractive market.

This year, FrieslandCampina acquired a majority interest in Alaska Milk Corporation, one of the largest dairy cooperatives in the Philippines, with a turnover of EUR 250 million. In the Philippines, too, where the economy and the population continue to grow, the dairy cooperative intends to sell baby and children’s food. These are mouthwatering prospects as far as investors are concerned. FrieslandCampina’s figures also confirm the security that dairy produce offers: turnover grew from EUR 8.3 billion to EUR 10.3 billion during the first four years of their existence.

Visible banking services

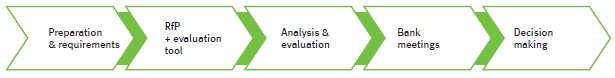

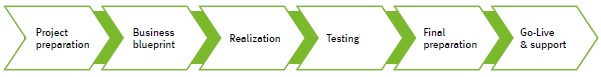

However, the merger began at a time when insecurity reigned supreme. The merger between the two dairy producers entailed a change of control situation that called for refinancing: the existing bank financing needed a make-over. This was quite a challenge, coming straight after the fall of Lehman Brothers and the start of the financial crisis. The banks weren’t exactly lining up to offer refinancing of this kind. For this reason, FrieslandCampina started negotiations with a wide selection of banks.

“The size of our wallet was important to the banks,” says Klaas Springer, FrieslandCampina’s director of corporate treasury. “They were perfectly happy to join FrieslandCampina’s group of financiers and commit themselves to our balance sheet, but they also wanted to earn money from the services that our internationally operating business needed. That was when we made a clear commitment: if you come on board, we’ll have a ‘best efforts’ obligation to reward you proportionally. After all, one bank’s service is better than another’s. If you finance 100 out of the 1,000 as a bank, it doesn’t necessarily follow that you will always get 10% of the wallet; the only guarantee that you have is that you will get the opportunity. A bank that has slightly more to offer FrieslandCampina, for instance, may get 12%, but if you’re offering less, then you may only get 8%.”

To be able to prove what the bank and FrieslandCampina had to offer each other, the relationship needed to be quantified. This is a considerable challenge given the various banking services that the organization needs – from ordinary payment traffic to cash management services, to setting aside deposits, foreign currency transactions, interest rate derivatives, and advice about acquisitions.

In order to make this complicated set-up more transparent, we looked for a model, an approach that we could ultimately manage properly ourselves. This is how we ended up with Zanders in 2010.

Klaas Springer, Director of Corporate Treasury at FrieslandCampina.

Wallet Distribution

An important part of the financing is done through private placements, including insurers in the United States. “In addition to this, we need bank financing to be the ‘flexible shell’ in our financing set-up,” says Springer. “We need the availability of large sums to deploy flexibly as working capital, for acquisitions or investments – i.e., for general corporate purposes. We try to cover virtually all our needs with this banking group that has provided us with EUR 1 billion. This doesn’t work with banks that only want to give you money but have nothing extra to offer."

“As a business, you have key relationships: the banks that you see as trusted advisors and that you are in touch with on an almost daily basis. Besides this, we also want a diverse group of banks that have a moral commitment to one another. They must all be prepared to stick their necks out so that it all goes well in the long term.”

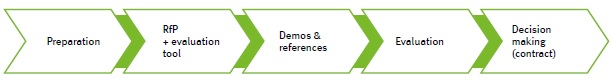

With Zanders, it was down to the Wallet-Distribution model when FrieslandCampina divided their portfolio across the banks they had selected. “That model was workable for us,” Springer says. “We were looking for a reliable Golf, not a Rolls Royce. We had to get the model up and running before entering all the data. Some banks are quick to give you insight into what they’ve done for you, and are quite open about it. But others are not so easy or flexible. Large international banks, for instance, don’t always have insight into what they’re doing for FrieslandCampina worldwide.”

Sander van Tol, partner at Zanders, adds: “They can’t consolidate all the internal information the way you want it, for example. Besides that, they don’t have sufficient insight into the overall portfolio of banking services that you use as a company. As far as that goes, to them, it’s like a game to see how they feature in the overall picture.”

FrieslandCampina used its own data for those banks that couldn’t supply the necessary information. Once everything had been processed in the model, it showed how much they were each entitled to on the basis of their contribution. Logically, some banks were happier with the results than others, but for most of them, expectations were met.

Open attitude

At the beginning of 2011, before the refinancing took place, FrieslandCampina approached its banks to discuss the results. Springer says: “At the time we said to our key partners: ‘This is how we see our relationship, how do you see it?’ The banks really appreciated this open attitude. They proposed the following: ‘We think we have X percentage of your FX management, is that correct?’ We didn’t give them an exact answer to that question – it’s all about the big picture, after all. The point of our story was that they would have to be happy with the information we shared with them and that FrieslandCampina had stuck to its side of the bargain. Apart from one or two, all the banks were satisfied. And we were able to explain to those few where the problem lay. To give an example: when we looked at cash management in the US, some of the banks fell by the wayside because cash management wasn’t part of their package – there was no point in inviting them. In this case, it’s not the Friesland Bank, but Citi, RBS, or HSBC who are invited. And that’s when there’s a winner. If a bank keeps missing the boat, then they get less than their share, proportionally. We say that something is not quite right: in the breadth, they simply don’t have enough to offer.”

Renewal

Shortly after the feedback from the banks, financial markets came under pressure once again in the summer of 2011, this time through the Greek debt crisis. In August, financing was discussed once more: the then EUR 1 billion facility was due to expire in 2013. “We approached the banks again and told them we wanted to refinance or renew the existing financing – but this time at a better rate.”

The banks recognized that they could benefit from a well-balanced cooperative relationship with the international dairy enterprise: the price wasn’t a major stumbling block for them. “It was more a question of timing, making an offer in a volatile market. All the big banks but one were with us in this respect. For us, renewing the financing until 2015 was better than new financing. We suggested that one bank join the rest. In the interim, we had two dark horses: banks that were keen to join the group. But, in the end, one bank agreed to the proposal.”

Apart from removing insecurity, the renewal proved to be a good solution from a cost point of view as well. Springer notes: “In 2009, we had to pay fairly high fees; it was a difficult market. By renewing now, we spread the costs that we incurred then over several years. In retrospect, the financing turned out to be cheaper than expected.” It won’t be possible to renew again, though. The firm will have to make a new deal. “A disadvantage of this is that you have to include all the costs that you incurred in the old transaction in your profit and loss account in one go,” Springer explains.

Highly commended

Every year, Klaas Springer sees the Adam Smith Awards announced in trade magazine Treasury Today. “And that’s when you think: have we got anything special to contribute this time round? This time we had a combination: throw the spotlight on portfolio management as a banking service and managing a refinancing project under very difficult market conditions. We decided to compete: we didn’t quite win, but we got a ‘highly commended’. The silver medal – enough to put us on the list of honors.”

An even better example is FrieslandCampina’s member bonds. “This is a financial instrument that is counted as stockholders’ equity from an accounting point of view. We pay interest on it that’s tax-deductible and it gives our members registered bonds that they can trade with one another. It gives a good return and has been accepted. We have now issued more than a billion, but it seems that the demand is greater than the supply – it’s an extremely successful instrument. Other cooperatives are asking us for advice on how these bonds are issued.”

Corporate treasury is not alone in feeling proud of the honorable mention; the corporation as a whole is, too. Springer sums it up, saying: “Wallet sizing put the ball in our court. We used it to get the signatures we needed for the refinancing. We managed to achieve something that doesn’t happen very often in the current market.” In 2012, FrieslandCampina passed the EUR 10 billion turnover mark. “We’re playing in the Champions League, our CEO is now saying. We’re no longer low-profile; we can’t hide anymore.”