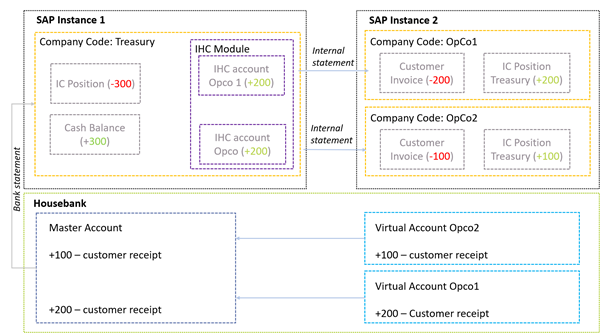

The process where virtual accounts are managed in IHC is depicted below:

In this process, we rely on a simple set of building blocks:

- In-house cash accounts to manage intercompany positions between Treasury and OpCo’s,

- GL accounts to represent external cash and the IC positions.

- Processing of external bank statements,

- Distribution of internal bank statements from IHC towards the OpCo’s ERP system,

- On the external bank statement for the Master Account, an identifier needs to be available that conveys to which virtual account the actual collection was originally credited. This identifier ultimately tells us which OpCo these funds originally belongs to and which IHC account to credit.

The idea here is that Treasury will receive the external bank statement and automatically post the receipts into the correct IHC account using the identifier. By posting items on the IHC account, the intercompany positions are updated. Then, at the end of the day, a set of internal bank statements is generated in IHC and sent through an interface to the OpCo’s ERP. The OpCo’s ERP processes these statements, clears out the customers invoices and updates the IC position with treasury.

The two major benefits of using IHC over the solution as described in the previous articles of this series are:

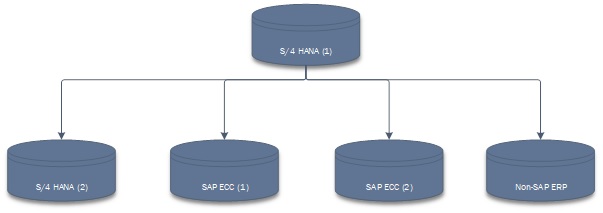

- The OpCo’s do not require any direct integration with the bank and can rely on internal interfacing with Treasury. Especially in companies with a fragmented ERP landscape this can become a valuable proposition.

- IHC can very aptly integrate virtual account management processes with internal netting payments, payments on behalf of (POBO) and payment in name of processes.

Implementing virtual accounts in SAP

In the explanation below we assume that the basic FI-CO settings for the company code a.o. are already in place. Also, it is by no means a complete inventory of all the settings that are required to get IHC up and running. It focusses more on the configurational parts that specifically cater for the VA requirements specifically.

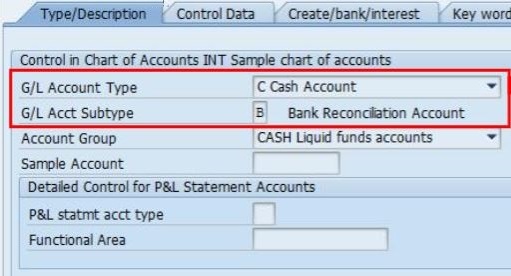

Master data – general ledger accounts

Three sets of GL accounts need to be created: balance sheet accounts for the representation of the intercompany positions, one set for virtual account clearing purposes between the EBS and the IHC accounting process, and the GL account to represent the cash position with the external bank. These GL accounts need to be assigned to the appropriate company codes and can now be used to in the bank statement import process and the IHC accounting process.

In the Treasury entity we should create a single GL (per position currency) representing the IC position with all its OpCo’s because the granularity of IC position per OpCo is managed in the IHC subledger. This approach results in less of an increase of accounts in the chart of account.

Transaction code FS00

House bank maintenance bank account maintenance

In order to be able to process bank statements and generate GL postings in your SAP system, we need to maintain the house bank data first. A house bank entry comprises of the following information that needs to be maintained carefully:

- The house bank identifier: a 5-digit label that clearly identifies the bank branch.

- Bank country: The ISO country code where the bank branch is located.

- Bank key: The bank key is a separate bank identifier that contains information like SWIFT BIC, local routing code and address related data of your house bank.

Transaction code FI12

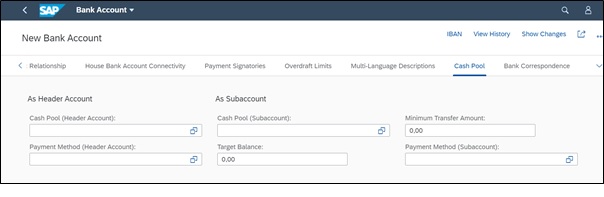

Secondly, under the house bank entry, the bank accounts can be created, including:

- The account identifier: a 5-digit label that clearly identifies the bank account.

- Bank account number and IBAN: This represents the bank account number as assigned to you by the bank.

- Currency: the currency of the bank account.

- G/L Account: the general ledger account that is going to be used to represent the balance sheet position on this bank account. Or the IC position with Treasury.

Transaction code FI12 in SAP ECC or NWBC in S/4 HANA

The idea here is that we maintain one house bank and bank account in the treasury company code that represents the Master account as held with your house bank. This house bank will have the G/L account assigned to it that represents the house banks external cash position.

In each of the OpCo’s company codes, we maintain one house bank and bank account that represents each of the IHC bank accounts as held with the treasury center. This house bank will have the G/L account assigned to it that represents the intercompany position with the Treasury entity.

Electronic bank statement settings

The electronic bank statement (EBS) settings will ensure that, based on the information present on the bank statement, SAP is capable of posting the items into the general or sub ledgers according to the requirements. There are a few steps in the configuration process that are important for this to work:

1) Posting rule construction

Posting rules construction starts with setting up Account symbols and assigning GL accounts to it. The idea here is to define at two account symbols, the first one to represent the external Cash position (BANK), and the second one for the virtual account clearing between IHC and EBS (VACLR)

A separate account symbol for customers is not required in SAP.

For the account symbol for BANK we do not assign a GL account number directly in the settings; instead we will assign a so-called mask by entering the value “+++++++++”. What this does in SAP is for every time the posting rule attempts to post to “BANK”, the GL account as assigned in the house bank account settings is used (FI12 or NWBC setting above).

For the account symbol VACLR we can assign a dedicated O/I clearing GL that is used to clear out the EBS posting against the IHC posting (more on that later). These GL accounts should have already been created in the first step (FS00).

Now that we have the account symbols prepared, we can start tying together these symbols into posting rules. We need to create 3 posting rules.

Posting rule 1 is going to debit the BANK symbol and it is going to credit VACLR symbol

Posting rule 2 is going to debit the BANK symbol and it is going to credit a BLANK symbol. The posting type however is going the be set to value 8 “Clear Credit Subledger Account”. What this setting is going to attempt is to clear out any open item sitting in the customer sub-ledger using algorithms. We will explain more on these algorithms below.

As you can imagine, posting rule 1 is applicable for the Treasury entity. Posting rule 2 is going to be used in the OpCo’s EBS process.

Transaction code OT83

2) Posting rule assignment

In the next step we can assign the posting rules to the so-called “Bank Transaction Codes” (or BTC’s like NTRF) that are typically observed in the body of the bank statements to identify the nature of the transactions.

To understand under which Bank Transaction Code these collections are reported on the statement, you typically need to carefully analyze some sample statement output or check with your bank’s implementation team for feedback.

Important to note here is to assign an algorithm to posting rule 2. This algorithm will attempt to search the payment notes of the bank statement for “reference numbers” which it can use to trace back the original customer invoice open item. Once SAP has identified the correct outstanding invoice, it can clear this one off and identify it as being paid.

If SAP is unsuccessful to automatically identify the open item, it can be manually post processed in FEBAN or FEB_BSPROC.

Transaction code OT83

3) Bank account assignment

In the last part, we can assign the posting rules assignments to the bank accounts. This way we can differentiate different rule assignments for different accounts if that is needed.

Transaction code OT83

4) Search strings

If the posting rule assignment needs more granularity than the level provided in step 2 above (on BTC level), we can setup search strings. Search strings can be configured to look at the payment notes section of the bank statement and find certain fixed text or patterns of text. Based on such search strings, we can then modify the posting behavior by for instance overruling the posting rule assignment as defined in step 2.

Whether this is required depends on the level of information that is provided by the bank in its bank statements.

Transaction code OTPM

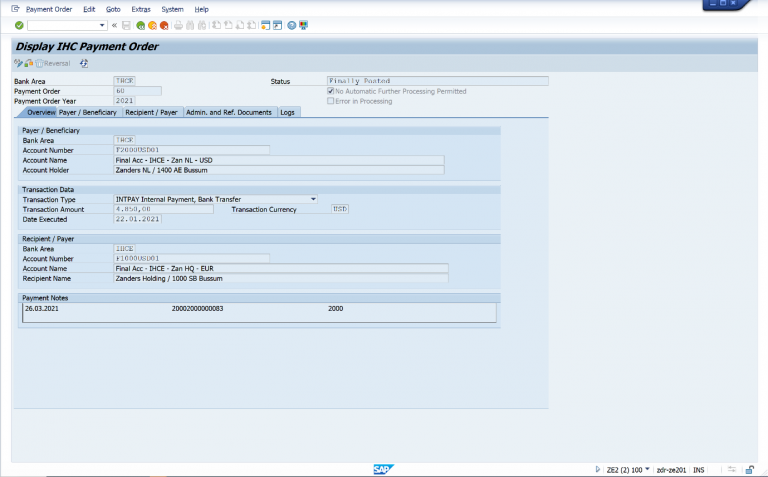

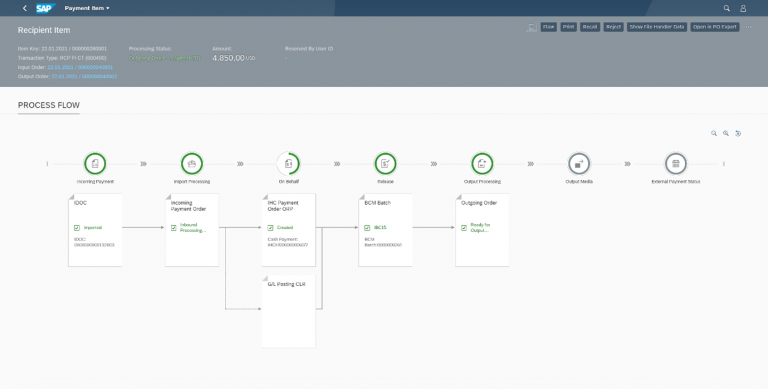

Prepare IHC to parallel post certain bank statement items into IHC accounts

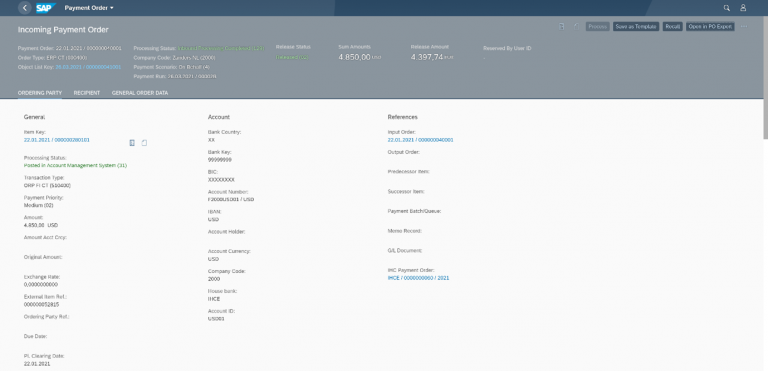

In IHC there are two ways to parallel post bank statement items into IHC accounts; as payment items or as payment orders.

This can be controlled by setting a specific function module on BTE2810. If we set function module “BKK_IHB_BASTA_IN_POST”, SAP will post an IHC payment item. If we assign “IHC_APPL_XBS_POST”, SAP will post an IHC payment order.

Additional information can be found in note 2370212.

In the subsequent part of the article we assume that we use the payment item logic.

Transaction BF42

IHC account determination from payment notes

In this section of the configuration we can determine which IHC account should be used to post the bank statement items towards using payment notes search strings.

For example, if the master account bank statement payment notes for VA collections for a particular VA contains a string “From VA 54353” and we know this belongs to IHC account “F4000EUR01”, we can setup a rule in this part of the configuration for that. This will ensure that all items on a bank statement containing this text string will get posted into IHC account F4000EUR01.

Maintenance view TBKKIHB1

Assign external BTC to posting category

Here we can identify the external banks BTC codes (NTRF, NCMZ a.o.) which are applicable for the VA movements to post into IHC. Secondly, we can identify with which posting category to post them into the IHC accounts.

Once we identified the BTC code related to our VA collections (e.g. NCMZ), we can link them to the correct posting categories here. You could use standard categories 90 (Balancing Ext. Acct (D)) for debits and 91 (Balancing Ext. Acct (C)) for credits.

Alternatively, you can setup and link your own custom posting categories here to more precisely control how our VA collections are posted into IHC. This is out of scope for this article though.

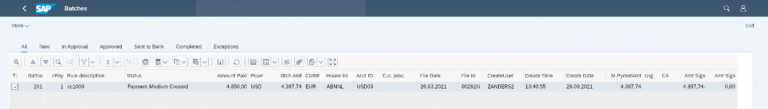

Importing and processing bank statements

We should now be in good shape to import our first statements. We could download them from our electronic banking platform. We could also be in a situation where we already receive them through some automated H2H interface or even through SWIFT. In any case, the statements need to be imported in SAP. This can be achieved through transaction code FF.5. The most important parameters to understand here are the following:

- File parameters: Here we define the filename and storage path where our statement is saved. We also need to define what format this file is going to be, i.e. MT940, CAMT.053 or one of the many other supported formats

- Posting Parameters: Here we can define whether the line items on the bank statements are going to be posted to general or sub-ledger.

- Algorithms: Here we need to set the range of customer invoice reference number (XBLNR) for the EBS Algorithm to search the payment notes for any such occurrence in a focused manner. If we would leave these fields empty, the algorithm would not work properly and would not find any open invoice for automatic clearing.

Once these parameters are maintained in the import variant, the system will start to load the statements and generate the required postings.

Transaction code FF.5 / FEBP

Display IHC account statement

Now that we successfully loaded an external bank statement, we can now check whether the items are posted into the IHC account. This can be done via transaction code F9K3. For each IHC account we can now look at the “Account Turnover” and observe all the VA collections that are posted on the account.

Transaction code F9K3

Prepare the IHC account for FINSTA statement distribution

We need to enable the distribution of internal IHC statements to the OpCo’s ERP on the IHC account master record. This can be achieved via F9K2. On the “Account Statement” tab we can adjust the statement format to “FINSTA” and dispatch type to “ALE” to ensure we are going to send FINSTA statements over an ALE connection. This would be the most common combination; other combinations can be configured and selected here as well.

Transaction code F9K2

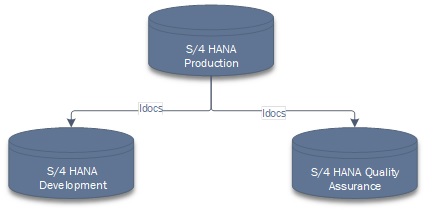

Setting up ALE partner profiles

Finally, we can configure the system to determine to which system the FINSTA’s need to be send. This can be done in WE20, partner type GP (business partner).

Here we need to setup the outbound parameters for the FINSTA message type. An appropriate port needs to be selected that represents the ERP of the OpCo.

Transaction code WE20

Trigger the distribution of a FINSTA statement

Now that we have some transactions posted on the IHC account and the FINSTA settings enabled, we can trigger the system to send the FINSTA statements to the receiving ERP system. This can be done in F9N7.

Here we can select the correct IHC account and statement date and run the program to generate the FINSTA statement.

Once the finsta is generated and sent to the receiving ERP, it can be processed there via FEBP there.

Transaction code F9N7

Closing remarks

This is the third part of a series on how to set up virtual accounts in SAP. Please find below the other articles on this subject: