Wilfred Nagel is member of the executive board and chief risk officer (CRO) of the ING Group. He is also CRO of the Management Board Banking. Nagel joined ING in 1996, holding various positions: head of financial engineering at ING Bank, country manager Singapore, head of project & structured finance (Asia), head of regional credit risk management (Asia) and head of regional credit risk management (Americas). In 2002 he was appointed head of group credit risk management, followed by his appointment as CEO of ING wholesale bank Asia in 2005. From 2010, Nagel was CEO of ING Bank Turkey, until he became board member at Bank and Insurance in October 2011. Nagel started his career in 1981 at ABN Amro as a management trainee, after obtaining his degree in economics at VU University in Amsterdam.

This summer, William Coen, secretary general of the Basel Committee, said that the end is nigh for post-crisis reforms to banking regulations, and that the focus is now on implementing them. Do you agree?

"This is probably more wishful thinking than reality. Enthusiasm in politics, the media and academia, and as a spin-off also in the regulatory world, for creating ever stricter rules, has not yet diminished. But at the moment you can’t tell if it’s enough or not. What is important is to stop for a while, implement, look at the impact and then decide what’s missing. What we now have is a continuous introduction of new regulations while previous ones have not yet been implemented or their effect felt. A number of them have a phased timeframe, such as CRD4. The question is: are we giving ourselves enough time to discover what the impact is? The amount of time and work it takes to implement new rules and see what they do for your company is often underestimated. The current dilemma for ordinary banks in most countries is that the savings side is growing faster than the lending side, so there is excess liquidity. The future capital demands for interest risk in the banking book means that longer-term investing can put pressure on the capital position. On the other hand, short-term investment with the current interest rate is bad for results. In fact you should really turn your back on the savers. However that is not in line with our customer-oriented strategy and could eventually cause problems with the NSFR. This is a typical example of how different rules, market conditions and client satisfaction are difficult to unite."

Are Dutch banks still viable after introduction of the CRSA floor (Credit Risk Standardized Approach) which has a significant impact on capital requirements?

“Although I am a risk manager, I am also a bit of an optimist. There is a lot of opposition to the introduction on many fronts, and the impact on economic recovery in Europe could be enormous, so I don’t think that it will be introduced exactly as set out in the consultation papers. But I am fairly sure that something will happen with it and that the average risk weighting adopted will be higher. And then banks with (Dutch) property mortgage portfolios on their balance sheets will be fairly vulnerable. At ING we consider ourselves lucky, because this accounts for about 15% of our global balance sheet – other banks have a much higher percentage. So, can we continue banking? Yes but we will have to change our business model with regards to this point. The business model we use is basically: we grant a loan, keep it on the books for its whole duration and the client pays us back over a period of 15 to 20 years. This is no longer applicable to a large proportion of mortgages. After security checks, they will be passed over more often to institutional investors. The question is, how hungry are investors and how long will it take to turn the balance sheet around to what you want it to be. In the meantime, you, as a bank, are fairly limited in what you can do. Also, the ‘one size fits all’ attitude which is behind the latest proposals could be open to modification. Not everything with the same label is the same. Our Spanish mortgage book for example, is better than the German, Dutch and Belgian ones since in these last three countries a large proportion comes via brokers and in Spain it is only from our own savings clients; we know them. You have to keep your eyes peeled to find the hidden gems. While searching for those gems, we, as a sector, got ahead of ourselves and put too much faith in credit rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s. But where we do succeed, it’s disappointing to see that the regulators don’t take that into account.”

But ESMA makes it compulsory to work with Moody’s, S&P and Fitch.

“As input it’s fine, but the last step in deciding on a credit rating has to come from the bank itself. Hedge fund critics often overlook the fact that a significant factor in their right to exist comes from being able to give their own independent judgement on a loan, and by doing so can come to other conclusions and other market behavior than the large regulated banks, who find deviating from the norm more difficult. Too much of the same spells danger.”

Although I am a risk manager, I am also a bit of an optimist

Wilfred Nagel, ING Group’s Chief Risk Officer (CRO)

What do you think about the Financial Stability Committee’s proposal for a gradual decrease in the LTV limit (LTV stands for loan-to-value and shows the relationship between the loan and the home value) for mortgages up to 90%?

“I imagine that this is a problem – in this phase of the housing market’s moderate recovery and all the political sensitivity regarding affordable housing for starters. But if you look at it from a normal banker’s perspective, then a prepayment of around 80% on a house is not so strange. The question is whether or not people themselves should take more responsibility for the financial choices they make and their consequences. To save for a number of years and then pay a deposit of 15-20% of the purchase price is not so strange, is it?”

Considering the current low interest levels, is a steep increase in interest not inconceivable at some point? What do you think the consequences will be?

“Banks’ interest margins are under pressure with the current low interest rates. Every time we reinvest the return is less. Up till now banks have been able to compensate in several ways, for example, by lowering savings rates and becoming more efficient. We are also seeing a somewhat increased interest margin by shifting new production to segments with higher spreads, such as project financing and trade financing of certain transfers. At the same time risk costs are showing a gradual improvement in line with economic recovery. The results show that we have been able to manage but decline in the reinvestment returns continues, while there is a limit to what you can do on the savings side. Added to this, the new regulations demand we do relatively more long-term funding. We don’t need this anymore for cash purposes, but we do pay liquidity premiums for it. What is strange is that the traditional balance sheet pattern, where liabilities are a little shorter than assets – the classic gap – is very limited. You see the balance sheet moving more naturally again, but relatively speaking our gap is still much smaller than in a normal interest climate.”

How has ING’s risk management developed since 2008?

"We have focused on mitigating remaining risks that had caused problems during the crisis. Where we ran up against problems was in a couple of large areas, like the Alt-A-portfolio in America, and the project development side of our property company. Our financial markets business also faced hard times, but finally showed a loss for one year only. As far as capital was concerned it has always been self-financing even though the ROI was not very strong. Even so we have radically reduced our trading activities in the financial markets business. An important deciding factor was our expectation that capital demands for this segment would gradually increase. We also looked closely at the global markets in which our position was strong enough to play a significant sustainable role. But the most important exercise since 2008 is that we have rigorously plowed through all large concentrations in the books. When Spain was hit by the euro crisis in 2012, we had EUR 54 billion-worth of assets against about EUR 14 billion-worth of savings. Now we have EUR 28 billion assets and EUR 22 billion savings.”

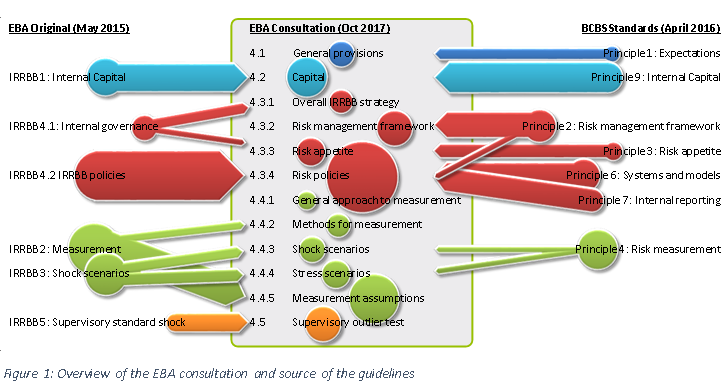

What impact will the possible introduction of the interest rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB) regulation from Pillar 2 to Pillar 1 have on ING?

“As I said, it will lead to a number of issues for liquidity management and for investment of our capital, which is the longest equity component a bank has. It is not something we are unduly worried about, but it is annoying that it costs capital and work again. Operational costs to comply with the regulations are considerable. The timing is also unfavorable. All banks are busy implementing an integrated finance and risk database. At the same time new regulations have to be implemented which can’t make use of that same database. So all sorts of parallel processes are being run that don’t link in to each other. What we learnt in our AQR (asset quality review) is that it’s not just an adequate database that’s important, but also the ‘query blanket’ on top of it, with which you can define search actions. We have upgraded it for the AQR and are trying to link it to the underlying data stream. We hope to complete the whole process, which was started in 2013, in 2018.”

And what are the priorities for ING for the future?

“The system that collects and invests savings, and another one that produces loans and tries to find funding are going to be more synchronized. We call this strategy ‘one bank’. Collecting franchise money country by country is fine, but if it is at all possible we will have to generate assets ourselves. We want to see a diversified balance sheet per country and are looking more critically at the impact of accounting treatment. If you study our own-generated loan books during the crisis, then they have done well. Of course there is extra pressure on the accounts in a crisis, but that is typical for banking. During the good years you have almost no provisions and a ROI of 20 and in a bad year you have considerably more provision and a ROI of 7. On average you make 13 and everyone is happy. What we have to avoid are large investment portfolios and asset concentrations.”