In business, success and failure are never far apart. Among the many different options available, management has to select those initiatives that can be managed with (limited) corporate resources in terms of capital, people and time available. The aim of the game is to maximize shareholder or stakeholder value.

Estimating the potential for the creation of shareholder value or economic ‘value add’ of a project is not rocket science. Any project with a positive net present value (NPV), where the cash flow is discounted at the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), should increase shareholder or economic value. However, experienced business managers know that in reality this is not that easy.

Management has always tried to include some objectivity in project selection in order to avoid personal risk. There are a wide range of methods and models for calculating and ranking the NPVs of projects under review, but most models are a variation on discounted cash flow or real option methods. While many of these are complex and cumbersome to use, if not ineffective in day-to-day business, others in contrast are far too simple.

The model selected will affect the estimated shareholder value created as well as the ranking of projects. Without careful examination, a model or method could provide a false objective measure to determine the value created. This is not because the formulae are incorrect, but because the input assumptions applied by the analyst are often taken for granted and not properly understood.

This article examines to what extent input, assumptions and models used for project selection could create a biased opinion of the creation of shareholder value. Companies should also make sure that the investment proposals allow management to compare individual projects and select those that make the best contribution to the creation of shareholder value. Treasury, as a custodian of risk management, could be the internal consultant to management in preparing and substantiating decisions on the allocation of a company’s limited resources.

Scope of Projects

Projects are different from business operations because they require a team of (hand-picked) people to achieve pre-defined objectives within an agreed timeframe, as well as an (upfront) agreed investment.

Once the objectives are achieved and the output is handed back to the business, the project and its organization is dissolved.

Typically, projects are created to improve or expand business operations but the nature and effect of a project can vary widely. For instance, a project on the acquisition and integration of new business is different to a project to develop and introduce a new product. A calculation of the shareholder value created can, of course, help to prioritize all these projects but because the effort, scope and risk of each project are different, companies must make sure they make accurate and meaningful comparisons between projects.

1. Cash flow projections

Each model starts with a forecast of project cash inflow and outflow. By its very nature, the validity of a forecast is highly dependent on the underlying assumptions, and most models recognize that cash flow projections cannot be 100% accurate.

More complex models include a sensitivity testing function but this takes considerable effort to build.

Many companies take shortcuts by varying the net or gross cash flows as calculated for the base case. These shortcuts might give an inaccurate view because varying the value of (net) cash flow does not recognize the fact that delayed projects could incur not only higher cost but also costs over a prolonged period. As a result, revenues could be lower than anticipated or the expected cash inflows from that project may be delayed. In fact, any delay to the anticipated cash inflow can have a disproportionate effect on the NPV of the project.

A second issue related to cash flow projection is what elements should be included. Some companies include only ‘hard dollar savings’, ignoring ‘soft dollar savings’, such as unlocking partial full-time equivalents (FTEs) allowing staff to focus on (other) value adding activity, or existing cash flow that might be jeopardized if the project is not accepted.

Other benefits, such as security, market perception or quality of data, are even more difficult – if not impossible – to quantify. And, even if they were, it would still be difficult to quantify their contribution to individual projects.

The more companies focus on ‘hard dollar savings’, the more projects will need to focus on core business operations. As a result, projects that would significantly improve the quality of management information systems without reducing headcount might be overlooked. Short and low risk projects with a small upfront investment will be considered a higher priority than larger, more risky projects. For instance, projects building on existing infrastructure to create incremental benefits will typically be favoured above projects that result in a paradigm shift within the organisation.

A third issue is the horizon of the cash flow projection.

For comparison purposes, companies often have standard projection horizons of three or five years. However, the longer the project implementation takes, the longer it will take for the benefit to materialize.

Prefixed horizons favour projects with ‘quick wins’, low investments and short implementation. Important infrastructure projects might not return a significant positive NPV over a three-year period. On the other hand, projects with lasting ‘quick wins’ contribute a benefit after three, four or even 10 years – long after anybody would even remember the objectives!

If one sets the horizon of projections in a different way for each project, comparing the projects will not be straightforward. If one assumes that projects are considered only to the extent that they enhance shareholder or stakeholder value, the relevant horizon should be adjusted to the profile of stakeholders.

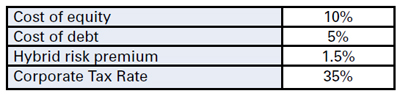

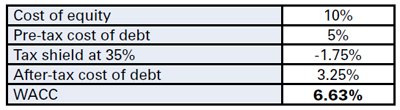

2. Discount factor

After the projections have been validated, the next step is to discount cash flows in order to make the NPV comparable. In theory, the WACC represents the rate at which projects will start generating shareholder value. The WACC is the weighted average cost of capital though and if a company is treated as a portfolio of projects, the WACC is a reflection of all activities and risks inherent in the company’s businesses.

Furthermore, the WACC is not constant over time. Among other factors, the WACC depends on the risk free rate, the company’s funding strategy (leverage) and risk profile. Each of these factors will change over time and can be different for each business line or project. The cost of capital should therefore be agreed individually for each project, and there are a number of issues that need attention.

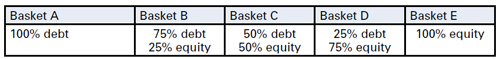

Allocation of equity and debt

The allocation of equity and additional funding to projects is an important factor for the calculated NPV.

Using the current WACC for the calculation disregards the effect a project might have on company leverage when approved. Using the current WACC will also underestimate the shareholder value created by the project if additional (senior) funding is put in place.

However, in a similar case, the marginal approach to the project cost of capital would allocate all new (senior) funding disproportionately to the new project and thus overestimate the shareholder value to be created.

Another approach to this issue is to estimate the risk profile of an individual project and allocate equity accordingly. Depending on the magnitude and profile of projects in the portfolio, this might imply that a company could have a temporary or permanent equity surplus (or shortage). All projects should then compensate for this difference in order to satisfy stakeholders’ requirements.

A project cost of capital curve

The WACC will change over time as a result of market fluctuations and funding strategies. It is therefore not unreasonable to discount the first year cash flow at a different rate than that of the fourth or fifth year. The curve for the cost of capital for an individual project does not have to correlate to a risk-free yield curve.

The leverage strategy and change in the company’s risk profile will also affect this curve.

3. Identifying project risk

Each project will have a specific risk profile. The real option method tries to treat each risk component as a decision ‘option’ and estimates the value of each one using standard option calculation methods. The result of this approach to project risk is dependent on the predicted accuracy of the decisions, likelihood of each option available and timing of such occasions.

The more options involved in each decision, the more difficult it will be to verify the assumptions and thus validate the outcome.

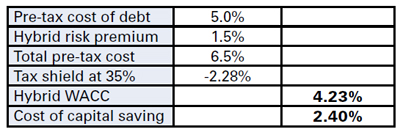

Other simpler and widely used models will increase the discount factor with a risk premium. This approach will not favour projects with a high upfront investment and long impact horizon. Outsourcing projects that convert fixed investments into variable cost might also benefit disproportionately from this approach to project selection.

Risk is project specific and sometimes even option specific, i.e. two alternative approaches to the same project might have different risk profiles. The case for outsourcing a project to two different countries might have an identical cash flow; however, the market might see one as a higher risk than the other (e.g. as a result of additional country risk). Allocating additional equity to one project or adjusting the company WACC with a country specific outlook are alternative approaches for incorporation of such risk elements.

Individual projects can potentially affect the overall company risk profile. Acquisitions or major investments could affect the company beta and change the overall cost of capital. If these changes are not incorporated in the project NPV, the contribution to shareholder value can easily be misjudged. A marginal approach to allocating the cost (or benefit) of changing the company risk profile is tempting, especially when companies execute a diversification strategy. However, quite a few companies do feel the pressure of trying to capitalize on a break-up premium.

To address the element of risk, some methods will use a less complex approach by increasing the standard project discount factor. This risk factor might vary from project to project and this approach to risk favours projects with ‘quick wins’ early on in the project. This can be at the expense of projects with long-term structural impact because of the reduced NPV of cash flows over a long period of time. For the same reason, the method also favours projects with small upfront investments.

A Role for Treasury

In order to substantiate and motivate the value created by projects, companies need to ensure that cash flow projections and project risk are modelled in such a way that the outcome is comparable. Project support offices (if available) are hardly ever equipped for this task.

Treasury as the custodian of cash forecasting, risk management and fair value calculation, is ideal for this job. It would make perfect sense for treasury to develop useful models for project managers and evaluate the business case documents for executive management. In this way, treasury would be able to reinforce its role as an internal consultant on cash flow and risk management.

Conclusion

Many companies put a lot of effort into modelling the benefits of projects prior to approval. Allocating scarce resources in order to ensure a successful project is an important responsibility of management and they should understand how an adopted model is applied within a project.

Validating the motivation behind input and stress testing of cash flow projections is probably more important than the fact that, on paper, projects will return the value that makes them eligible for approval. Treasury can use its expertise to assist management and make sure the company chooses the best projects.

It is important to look beyond mere numbers and not focus on the difference of 1% or 2% in the NPV; remember there is always an element of art and ‘gut instinct’ in project selection. Management should therefore treat project analysis as a tool to support their strategic decision-making within the company.