Empowering Customer Due Diligence specialists with an AI-driven chatbot for accurate, instant query resolution.

We assisted a private Dutch bank in managing the overwhelming volume of queries from bankers regarding Know Your Customer (KYC) and Customer Due Diligence (CDD) by developing an AI-powered chatbot.

Challenge

Bankers frequently needed specific information to assess customer profiles, verify identities, and evaluate potential risks to comply with regulatory requirements and ensure due diligence. However, this information was scattered across approximately 30 documents in various formats, including Word documents and PDFs. As a result, CDD specialists were overwhelmed by a constant stream of queries, making the process inefficient and increasing the risk of inconsistent or inaccurate responses.

To address these inefficiencies, the client sought a solution to streamline information retrieval and provide accurate, consistent answers.

Solution

Zanders proposed a step-by-step approach to developing the CDD chatbot:

1 - Investigating requirements from CDD specialists and bankers.

2 - Developing the chatbot using Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG).

3 - Optimizing performance through rigorous validation.

4 - Deploying the chatbot for live use by the client.

In the initial phase, we held discussions with both CDD specialists and bankers to identify their key requirements. It became evident that the chatbot needed to deliver accurate, reliable information while ensuring response consistency. Given these requirements, the unstructured nature of the data, and the chatbot’s internal use case, we determined that a Generative AI (GenAI) chatbot would be the most effective solution.

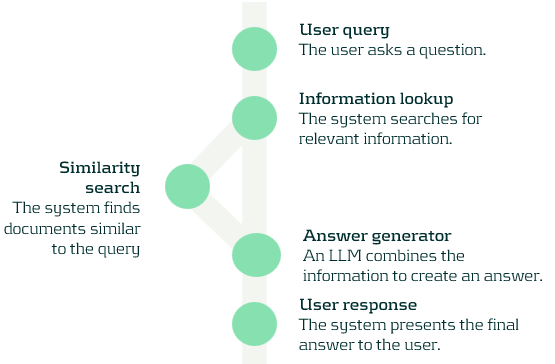

For development, we leveraged Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), a method that combines fast and relevant information retrieval with the power of advanced AI to generate accurate, context-aware responses. This ensured a reliable and informative user experience. The processes in this approach are shown in the figure below.

To validate the chatbot’s performance, we created a dataset with expected responses, fine-tuned hyperparameters, and conducted extensive accuracy testing.

Finally, to ensure a seamless deployment, we established a structured system for development, deployment, and continuous improvement. By leveraging pre-trained large language models (LLMs), we were able to rapidly deploy the chatbot and refine it based on real-world user feedback.

Performance

As a result, the client successfully implemented the CDD chatbot, allowing users to query the document corpus directly and receive responses in plain English, along with a list of reference sources used by the LLM. Thanks to the RAG approach and thorough validation, the chatbot consistently produced accurate and reliable answers.

The chatbot has significantly improved efficiency, enabling CDD specialists to manage inquiries more effectively while helping bankers conduct due diligence with greater speed and accuracy. This has led to a more streamlined and reliable CDD process.

For more information, visit our Financial Crime Prevention page, or reach out to Johannes Lont, Senior Manager.

Remote partnered with Zanders to simplify bank onboarding, enabling seamless global operations and innovative remote work solutions.

Remote offers global employment services for internationally distributed workforce. It takes care of payroll, benefits, compliance, taxes, equity incentives and more, so that companies can employ someone internationally as easily as they do at home. The company’s vision is to make it simple to manage, employ, and pay anyone, anywhere. Founded in 2019, Remote is growing quickly and expanding into different markets. In 2022, Zanders supported the company to accelerate the onboarding of new banks. Ana de Sousa, Director and Global Head of Treasury at Remote, explains the collaboration in this Q&A.

"We tackle some of the biggest challenges involved in building distributed teams, which are the risk, cost, and complexity of employing international employees and contractors,” De Sousa clarifies. “Our customers include GitLab, DoorDash, Loom, Paystack, and thousands of other companies around the world.”

You have been Director Global Treasurer at Remote for a year now. What attracted you to join the company?

“At Remote we often say that ‘talent is everywhere, but opportunities aren’t.’ I grew up in a very small village in Portugal so I personally identify with this. I saw that Remote is changing the world and I wanted to be part of this change. Beyond the mission, it’s also exciting to be part of a company that is applying technology and automation to bring efficiency to an area as complex as global employment. I am also very aligned with Remote’s values. The value of kindness is very special for me, as I believe that we can always make extraordinary things when we are kind.”

How would you describe the company’s corporate culture?

“Because Remote is a fully distributed virtual company with no offices, most roles are country-agnostic and our employees can work from their chosen locations around the world. That means we have Remoters from 75+ different nationalities, coming from all different cultures, backgrounds and experiences. This contributes to a diverse work environment where everyone is encouraged to share their culture and interests with everyone.”

What would you say drives the need for remote work/remote hiring and remote services in general?

“Over the past few years, many companies turned to remote work as a solution to a problem. What they are discovering now is that it can provide significant business advantages as well. Remote work enables you to build a team without being constrained by geography, meaning companies can tap into wider pools of talent while also supporting greater flexibility and work-life balance.”

What is your experience within different regions/markets?

“Remote has a global presence with around 80 legal entities on six continents. I started my career overseeing cash management for the EMEA region. Later, I moved to a new job with a global scope. Here at Remote, every single member of the Treasury team has global coverage. This means we can leverage asynchronous and flexible work for the entire team to be effective.”

You are working completely remotely, without having a physical company office. What has been your experience with this setup and do you miss meeting your colleagues in person?

“I do miss team birthday parties with cake sometimes. I advocate freedom of choice, based on whatever is best for you. Working from an office is still offered by plenty of companies. For me, remote work has allowed me to keep my career in an international environment while prioritizing family and flexibility. It’s certainly still possible to meet up with colleagues without a company office. I recently met one of my team members in person for the first time, and it was just like catching up with a friend.”

In terms of managing family/work time, are there days where you would prefer to work in a physical company office?

“No, I manage my time according to my priorities. If my kids need me, I will be available for them. If my work is my priority, that is my focus. It is not a physical place that defines my commitment or my capacity of producing results. It is important to have the right structure that supports your professional career independently of the place.”

What are the communication tools you use internally and externally?

“We use tools like Slack, Notion, Loom, and Asana for communication and documentation. Beyond the tools, Remoters are trained in asynchronous communication, documentation, inclusive language, meeting best practices, and even to use the UTC time zone companywide. These are all essential for a team that is as distributed as ours.”

What would you say are treasury-specific challenges when working remotely?

“The biggest challenges of remote work arise when we try to take the old office-centric methods of doing things and expect them to work just as well in a remote setting. Remote work does require some different considerations. Treasury teams in particular need to be rigorous about documentation and practicing ‘overcommunication’ given the critical nature of our work.”

What is the company’s approach for creating an integrated team and what is your personal approach to build a team spirit while working completely remotely?

“As a fully remote company, Remote works hard to build belonging and a sense of community throughout the company. There are numerous opportunities for social connection, including bonding times, games, and even virtual reality time. We have more than 1,700 Slack channels including channels for music, TV, pets, food, sports and much more. At the same time, our culture is asynchronous, so people can participate on their own time and all scheduled events rotate across time zones.”

Expanding into new markets is part of Remote’s core strategy. What role does Treasury play to enable new country operations?

“At Remote, Treasury is part of the backbone of our operations and an enabler of international growth. In the majority of cases, without a bank account, we cannot launch in a country. In addition, domestic bank accounts are also critical to offer better experience to our customers.”

How did Zanders support you to accelerate the onboarding of new banks?

“Zanders helped streamline what could be a very complicated process with banking partners. We appreciated their continuous communication and follow-up on progress, as well as their advocacy on our behalf to challenge some of the requirements we faced and even get a few of them waived.”

How did you perceive the collaboration between Remote and Zanders, given the project was delivered on a fully remote basis?

“It worked very well. We would not have been able to work with a partner that didn’t know how to collaborate remotely. Working with the Zanders team, we were able to apply the same operating principles we use internally – clearly defining guidelines and expectations, overcommunicating, and building a high degree of trust between our teams.”

To round off, what advice would you give anyone starting to work 100% remotely?

“Life is too short to waste time commuting. Remote work is all about freedom, flexibility and happiness. When we do what we like, we’ll get great results, regardless of where the work is done.”

The collaboration between Remote and Zanders

Viktorija Janevska, manager at Zanders: “Account opening and KYC has been a challenge for many corporates in recent years, given the increasing KYC requirements and rather cumbersome onboarding experience. We at Zanders have been happy to support Remote with this interim project, taking the workload from the team and being the first point of contact for the banks with regards to the account opening and onboarding documentation requests. Key success factors for the project were the open and transparent communication between the two teams, regular update calls and priority setting.

Remote not only demonstrates an innovative working approach when it comes to working remotely, but also by using chats for most of their internal communication rather than email communication. During the project, the transition from email to chat communication required some adaptation and from time to time a reminder to use the preferred channel. It has been a great experience to accompany Remote on its journey and are looking forward to see the company’s further success.”

Lee-Ann Perkins shares expert insights on mastering risk and project management, empowering treasury teams to future-proof their strategies and drive impactful change.

As one of our key clients, we had the opportunity to speak with Lee-Ann Perkins to gain some insight on two topics that almost every treasury team at one point or another will have to grapple with – risk management and project management.

During one of our discussions, you mentioned how risk management is perhaps not given the appropriate level of consideration that it demands. Can you please elaborate on this and explain how the treasury team of an organization can address this issue?

"The treasury department’s purpose is to safeguard the financial assets of the company. In doing so, we control the financial risks by conforming with board and internal policies and shareholder needs. Risk is inherent in the treasurers position and often this is overlooked and undervalued until a crisis hits.

We address and highlight the importance of risk management by ensuring our teams are curious, well trained, and informed. Start by allowing treasury the opportunity to ask questions and gather as much information as possible to ensure small misjudgments don’t lead to material costs down the road.

Treasury departments must be rigorous in ensuring compliance with established policies, procedures, and financial regulations. This is a non-negotiable aspect inherent in the position. We should guide conversations with the goal of strengthening processes to safeguard the company and its reputation.

I like the saying ‘A tsunami starts with small detectable waves’. And I believe that treasury departments are in a unique position to identify and evaluate risks and possible solutions. Treasury department is a financial function that both front faces (with banks, vendors, investors, rating agencies to name a few) and interfaces as partner of many internal stakeholders and areas of the business. These relationships, if well nurtured, can help the company to send solutions down the road to meet us when we most need them.

If given the resources, information and voice, Treasury can help the company manage and mitigate the causes of risk and not just the symptoms. Treasury departments have often been involved and brought to the table when a crisis has occurred. My mission statement for treasury departments, to use the Covid analogy, is: be the vaccine instead of the medicine! If you don’t manage risk, it will ultimately manage you!”

In addition to risk management, you also mentioned the importance of effective project management. Can you please share your experience in this area and what you learned through the process?

“It’s a well-known fact that treasury departments are often small and lack resources. Automation is a way to free up resources and allow treasury professionals to focus on strategy and risk management. Therefore, as we strive to automate and mature the function, projects have become integral in the treasury department’s strategy. Treasury professionals should have skills and abilities to effectively manage projects to success. We all know the saying ‘the devil is in the details’, which I agree with. But I take it one step further by stating that ‘the devil is in the details, but the success is in the strategy’.

In my experiences, project management has not been a part of treasury teams training. Due to the changing responsibilities of treasury professionals, we are often called upon to implement, change or enhance processes and/or systems. These projects require managing resources, selling ideas, implementing changes, and ensuring this is all done within the required budget and timeline. Success requires the practice of sound project management processes. These steps include planning (develop the project charter), organizing (create the organizational chart), leading (direct the resources) and controlling (continuous review of metrics). I learned this skillset in my MBA program, and it has served me well in leading multiple projects to successful outcomes. As this is most often a learned skill, I believe treasurers should advocate for training and development of this much needed skillset to ensure we follow the steps for successful project management.”

The topic of project management is quite often on the minds of treasury teams when they first contemplate the need to automate their systems. What advice would you give to an organization’s senior leadership that is forward-looking and seeking to adopt the benefits of technology but is cost-conscientious due to budgetary constraints?

“Firstly, I would say that this is the right attitude to embrace in the pursuit of future proofing and maturing the treasury department. Leaders have to manage company resources for the best and highest use of time and money. To compete for resources, treasury departments have to convince the leaders that their projects are in line with the company’s goals and strategy. Resource constraints are a real concern in companies. However, with proper planning and data-driven cost benefit analysis, these projects sell themselves when Treasury is able to demonstrate the quantifiable advantages.

Leaders should empower employees to utilize technologies for the intended purpose of creating efficiencies, providing information, and managing financial and operational risk through data and insights. Automation and dynamic forecasting systems proved particularly useful during the pandemic, when liquidity and short-term forecasts were crucial to run the business through unprecedented difficulties. Manually consolidating data can lead to missed opportunities and inaccurate information.

While treasury automation projects yield many benefits, they should be approached though a realistic lens. Projects should have a clear project charter, org chart, timeline and agreed-upon metrics to measure and demonstrate success. Automation projects have many stakeholders who need to provide input, assistance, and resources to ensure the desirable outcome. This requires thoughtful and deliberate planning and honest dialogue with all stakeholders.

When evaluating automation projects, the teams should ensure the systems are fit for purpose, scalable, and provide standardization, controls and audit infrastructure that will benefit the company. This approach allows companies to implement modules or systems that provide the most immediate beneficial impact and then scale up as they see the needs and benefits. I also suggest cloud-based systems for security, ease of implementation and cost.

My takeaway is to encourage leaders to ‘take the bot out of the human’, and allow treasury professionals to focus on capital structure, liquidity, risk management and meeting shareholder needs, and use technology to do repetitive transactions that help to simplify processes and reduce costs and errors while improving accuracy of information, data security and global standards.”

As versatile financial services professional, Lee-Ann Perkins has more than 19 years of domestic and international treasury management experience working in mid- to large-sized public and private organizations. She currently works as treasury professional at a global sporting and recreational goods and supplies company. Additionally, she is an Advisory Board member for Nacha, which governs the ACH Network, a member of the AFP CTP exam committee and treasury advisory group (TAG) and was previously the president of the Houston Treasury management Association.

In het voorjaar 2021 kregen de aandeelhouders van de Provinciale Zeeuwse Energiemaatschappij (PZEM) eindelijk zicht op hun lang gekoesterde wens: direct aandeelhouderschap in Evides. Doel daarvan was om het Zeeuws-Rotterdamse drinkwaterbedrijf volledig in publieke handen te brengen en het dividend van Evides te kunnen benutten. Voor de overname van de aandelen moest echter een beoogde financiering van 355 miljoen euro worden gearrangeerd en gestructureerd.

Op 8 december 2021 kwam het waterbedrijf Evides in publieke handen, nadat de aandeelhouders van PZEM hun belang in het bedrijf overnamen. De provincie Zeeland, samen met verschillende gemeenten, werd via de holding GBE Aqua directe aandeelhouder van Evides. Ondanks de verandering in aandeelhouderschap, blijft de operationele werking van het bedrijf grotendeels hetzelfde, terwijl het zich voorbereidt op grote investeringen in de komende jaren, zoals de vervangingen van waterleidingen en het voldoen aan duurzaamheidsregels.

Evides ontstond in 2004 uit een fusie van het DELTA Waterbedrijf en het Waterbedrijf Europoort. Het voorziet circa 2,5 miljoen klanten in heel Zeeland, zuidelijk Zuid-Holland en een klein stuk van westelijk Noord-Brabant van drinkwater en industrieel water. Na Vitens is Evides de tweede drinkwaterproducent van Nederland.

Het waterbedrijf had twee aandeelhouders. Naast Gemeenschappelijk Bezit Evides, bestaande uit verschillende Zuid-Hollandse gemeenten, is dat PZEM, het energiebedrijf dat tot 2017 onderdeel was van het Zeeuwse nutsbedrijf DELTA. De aandeelhouders van PZEM waren indirect aandeelhouder van Evides en koesterden al jaren de wens die aandelen in directe handen te krijgen. Dit betekent dat ze aparte aandeelhouderschappen wilden creëren voor het energiebedrijf PZEM en het drinkwaterbedrijf Evides. In de drinkwaterwet staat immers beschreven dat drinkwaterbedrijven in publieke handen horen te zijn. Daarnaast was er een financiële wens, omdat Evides dividenden uitkeerde waar de uiteindelijke aandeelhouders niet direct over konden beschikken.

Een nieuwe holding

Toen in 2020 de beoogde vestiging van de Nederlandse marinierskazerne in Vlissingen alsnog werd afgeblazen, is afgesproken dat provincie Zeeland een compensatiepakket zou ontvangen. Die ontwikkeling maakte een overname van de Evides-aandelen plotseling haalbaar, vertelt Britt Rijk, adviseur deelnemingen bij de provincie Zeeland. “We hebben het Rijk toen gevraagd hoe we de aandelen in het drinkwaterbedrijf zouden kunnen verkrijgen. Onderzoek wees uit dat we de aandelen tegen marktwaarde konden kopen. De vraag was echter hoe dat financieel moest worden ingericht, aangezien we het geld als aandeelhouders niet in kas hadden.”

De aandeelhouders besloten een nieuwe holding op te richten, genaamd Gemeenschappelijk Bezit Evides Aqua B.V., kortweg GBE Aqua. Deze holding zou, met een garantstelling vanuit de provincie Zeeland, de benodigde financiering aantrekken. “Om die garantstelling te kunnen afgeven, ontvingen we een bijdrage vanuit het Rijk. Zo kreeg een deel van het compensatiepakket voor de afgeblazen marinierskazerne een plek.”

Financiering met garantstelling

De marktwaarde waartegen de provincie de aandelen zou kunnen overnemen, werd in het voorjaar van 2021 bepaald op 367 miljoen euro. In mei nam de provincie contact op met Zanders, met het verzoek om te helpen bij het arrangeren en structureren van de financiering, het staatssteunaspect en de garantiestructuur van GBE Aqua. “We deden al vaker zaken met Zanders voor treasury- en financieringsvraagstukken. Zo hielpen ze bij North Sea Port en bij de provincie zelf al met een garantiestructuur. Daarom hebben we als provincie ook voor deze uitdaging een beroep op ze gedaan. Voor de financiering was een garantstelling nodig, maar of we die vanuit de provincie konden afgeven, wisten we niet – Provinciale Staten moest daar nog over besluiten. Hoeveel risico zou de garantsteller bij deze financiering lopen? Hoe moesten we dat beprijzen en wat was daarin marktconform? En wat zou dat alles uiteindelijk betekenen voor alle betrokken partijen? Die vragen legden we bij Zanders.”

Twee trajecten naast elkaar

Toen het project van start ging, lag het juridische stuk rond de staatssteun nog niet vast, vertelt Rijk. “Er moest dus nog heel veel worden vormgegeven. Veel ontwikkelingen in het traject liepen parallel, waardoor er ook veel moest worden geschakeld. Dat maakte het project heel dynamisch. Terwijl Zanders aan de financiering werkte, waren wij nog druk bezig met het oprichten van de nieuwe BV. Alle aandeelhouders van PZEM, die ook aandeelhouder wilden worden in GBE Aqua, moesten de overname goedkeuren, waarbij alle voorwaarden en risico’s van de overname van de aandelen werden besproken. En we wilden voor eind 2021 alles geregeld hebben.”

“Eigenlijk deden we twee financieringstrajecten naast elkaar”, vertelt Koen Reijnders, die de Provincie namens Zanders adviseerde. “We hadden een financieringstraject met een 100% garantie van de Provincie en één met 80% garantie, waarbij dus een deel commercieel zou worden gefinancierd.”

Vanuit staatssteunoogpunt zijn beide trajecten doorlopen. Uiteindelijk heeft de Provincie gekozen voor een 100% garantie. GBE Aqua sloot op basis daarvan bij één bank een lening af van 355 miljoen euro om daarmee de Evides-aandelen van PZEM te verkrijgen. “Dat was een heel mooi resultaat”, zegt Rijk. “Met de realisatie van de financieringsstructuur zijn we een stuk beter uitgekomen dan we in de aannames hadden opgenomen. De rente bleek daarbij op een erg gunstig moment te zijn vastgelegd en zelfs negatief te zijn; kort daarna zette de stijging in. Het bracht bovendien duidelijkheid voor de aandeelhouders – zij wilden weten wat de financiering uiteindelijk zou gaan kosten. En dat ziet er nog beter uit dan ze op voorhand verwachtten.”

In publieke handen

Op 18 november 2021 werd tijdens een bijzondere aandeelhoudersvergadering van PZEM besloten dat de aandeelhouders het belang in het waterbedrijf Evides NV van PZEM overnamen. De dag erop was de financiering rond en startte GBE Aqua als holding. De formele aandelenoverdracht vond 8 december plaats, waarmee Evides in publieke handen kwam. De aandeelhouders kunnen vanaf dat moment rekenen op een structurele dividendopbrengst, die verschilt per jaar, afhankelijk van verschillende factoren. Ook worden de dividenden die GBE Aqua ontvangt, gebruikt om de bancaire lening af te lossen.

Samen met de Zeeuwse gemeenten, en de gemeenten Woensdrecht, Bergen op Zoom en Goeree-Overflakkee is de provincie Zeeland nu via de holding GBE Aqua direct aandeelhouder van Evides. De andere helft van de aandelen van het waterbedrijf zijn in bezit van 18 Zuid-Hollandse gemeenten.

Hoewel het bedrijf nu met een andere groep aandeelhouders aan tafel zit, heeft de aandelenoverdracht op Evides weinig operationele invloed. Net als alle waterbedrijven in Nederland staat het echter voor een aantal uitdagingen. Zo staat het bedrijf de komende tien jaar voor een grote investeringsopgave, omdat onder meer waterleidingen moeten worden vervangen, waarbij ze ook moeten voldoen aan de nieuwste duurzaamheidsregels.

Van risico naar aflossing

In deze grote investeringsopgaven speelt de komende jaren ook de vraag welke rol aandeelhouders daarin zouden moeten pakken. “Dergelijke vraagstukken zagen wij ook bij de financiering”, vertelt Rijk. “We hadden een dividendprognose van Evides waarbij de aflossing van de lening vanuit dat dividend moest plaatsvinden. Vanwege de investeringsuitdagingen is de verwachting dat het dividend de komende jaren lager zal zijn dan dit de afgelopen jaren geweest is. Dat zou betekenen dat de aflossing zo’n 60 tot 70 jaar zou gaan nemen – ook omdat de aandeelhouders een klein deel van het dividend vrij zouden willen kunnen besteden.”

Gedurende het proces bleek echter dat er vanaf 2022 ook vanuit PZEM een dividendstroom zou komen, omdat de resultaten daar beter waren dan verwacht – onder meer door de enorm gestegen energieprijzen. “Dat was een onzekere, maar belangrijke factor in de financieringsstructuur zoals die uiteindelijk is opgetuigd. Als er bijvoorbeeld iets zou gebeuren met de kerncentrale van PZEM, waardoor de centrale niet meer opgestart kan worden, moet daarvoor geld in kas zijn. Als Provincie waren we al heel lang aandeelhouder van PZEM – en dus ook van de kerncentrale. En in de afgelopen jaren was er vanwege de risico’s geen dividend uitgekeerd. Daar kwam dus een kentering in. Maar toen was de vraag: willen we dit geld gebruiken voor de aflossing? Die keuze was snel gemaakt; juist door de lening sneller af te lossen, neemt het risico van de aandeelhouders op deze lening af doordat in GBE Aqua meer middelen worden gecreëerd om dergelijke risico’s op te vangen. Uiteindelijk versnelt en vergroot dat daarmee de vrije kasstroom binnen GBE Aqua, die ten gunste van haar aandeelhouders komt.

Financieel en maatschappelijk rendement

Gevoed door de bijzondere rentemarkt leidt meer dividend soms tot een ander probleem, zegt Reijnders: “Als je meer dividend binnenkrijgt dan je eerder verwachtte en je daar in je financieringsstructuur geen rekening mee hebt gehouden, heb je overliquiditeit. Als je dat geld laat staan, heb je in de huidige markt te maken met negatieve rente over je liquiditeit. Maar als je het aan je aandeelhouders uitkeert, kun je het volgende jaar, wanneer de dividenden lager uitvallen, problemen krijgen met de aflossing. Naar dergelijke scenario’s hebben we dus ook goed gekeken.”

Ook andere netwerkbedrijven staan de komende jaren voor soortgelijke investeringsuitdagingen, zegt Rijk. “Vanuit de Provincie draait het dan vaak om zowel het financiële als het maatschappelijke rendement dat zo’n investering oplevert. Maar in ons geval gaat het er uiteindelijk om wat het Zeeland oplevert. Over de stap die we met GBE Aqua hebben gezet zijn we dan ook erg tevreden. De samenwerking met Zanders was heel goed en transparant. De goede combinatie van corporate en publieke kennis die ze in huis hebben, heeft daarbij erg geholpen.”

Wilt u meer weten over financiering of structurering? Neem dan contact op met Koen Reijnders.

LyondellBasell, headquartered in the Netherlands, is one of the largest plastics, chemicals and refining companies in the world.

LyondellBasell, with its global presence and significant operations in the United States, the company has been affected by the IBOR reform. The Treasury team was well aware of this impact and proactively approached the transition away from the IBOR rates in order to be ready ahead of time.

While it was a global and multi-functional project, one of the first goals was to ensure the TMS readiness for the calculation with alternative reference rates and the new discounting methodologies. As part of the action plan, the LyondellBasell (LYB) Treasury team (supported by procurement and IT) issued an RfP in Q4 2020 with the aim to get external support for (a) the required system changes, (b) to provide business support for initial transition plans and (c) to adhere to the best-in-class ambition of the company.

Preparing for the transition

LYB selected Zanders as implementation partner and right after the selection the project kicked off in January 2021. Urszula Chwala, was the Treasury Lead for LYB and she outlines why LYB initiated the project earlier than many other corporates: “The project team was already busy since the beginning of 2020. We analyzed the potential global impact of the IBOR reform to LYB. Amongst other impacts we were aware that LYB’s SAP Treasury Management System was highly customized, especially in the area of SAP In-house Cash. As such, we wanted to make sure that we would be ready for the transition to support our business and to enable all teams at LYB to move forward with changes on financial, commercial and legal matters.” Urszula also further comments on the RfP process: “We were looking into the third party that had both technical and business knowledge related to the IBOR reform and could bridge the gap between LYB IT and the Treasury department.”

Appreciated approach

LYB is using SAP ECC EHP8 as their treasury system and as such the standard functionality developed by SAP to support daily compound interest calculation could be implemented. On the Zanders side, SAP consultant Aleksei Abakumov, Adela Kozelova (who fulfilled the role of the business expert and project manager) and Anuja Naiknavare in the role of support consultant have been closely working with LYB’s Treasury and IT teams throughout the project.

Zanders made this project as easy as it could be. What I really appreciated was the approach taken by Zanders team. They have taken all the suggestions from us and tested them and then came up with additional suggestions as well. The Zanders team was thinking with us, taking our best interest in mind. They supported us in every detail and removed concerns and roadblocks. Zanders also acted as business alliance in the project to ensure that all business requirements are now fully translated into the technical solution.

Urszula Chwala, Treasury Lead for LYB

A new functionality

In order to achieve system readiness, the project included configuration and diligent testing of a new data feed source which was required as a base to enable the daily average compound, the simple compound interest calculation and the new evaluation type with enhanced discounting curves. Considering the uncertainty, the availability of the new alternative reference rates, market conventions and the exact timing, the project’s aim was to make sure that the system would be able to support different variations of interest calculation. The project went successfully live in May 2021.

Urszula outlines different challenges encountered in the project: “Technically the biggest challenge was finding the right market data feed for the new rates. The challenge was finding the source and, making it available in SAP and test all scenarios. For the actual transactions, the system is a lot more flexible with respect to entering transactions, which makes a deal capture more complex. But Aleksei has supported the team a lot in navigating through the new functionality and we are confident to enter new deals with overnight risk-free rates. On the business side, the market clarity, especially with regards to market conventions, is still challenging the business cutover.”

Transactions

On the transition side, Treasury was cautiously managing the exposure to the IBOR reform by refraining from entering variable interest rate referencing transactions over the last two years. As a result, there is no need to cutover of any existing transaction. However, there are few intercompany loans that will mature by the end of this year and some of them might be replaced by the deals referencing to the overnight risk-free rates. Having strong presence in the United States, the exposure to the USD LIBOR is considerably higher than to the GBP and CHF LIBOR ceasing at the end of this year. Therefore, the major transition is only expected over the next year, closer to the cessation of the USD LIBOR.

Urszula elaborates on the business transition: “Understanding the logic of how new instruments are going to work gives me a piece of mind for the transition. LYB never meant to be an early adopter of the change. Switching intercompany loans as first seems to be the best approach for us, because there are no corresponding derivatives needed for these products. Also, there is no dependency on the external counterparties, which makes the transition easier.”

Really achieved

LYB and Zanders are currently working on a follow-up project for the cash flow aggregation of interest in SAP. This need emerged from the new daily compounding functionality, which by default creates daily cash flow postings that are difficult to reconcile with the interest settlements. A user-friendly solution to aggregate these daily cash flows has been defined and configured and is currently being validated by the end users. This is the last step for LYB to be ready to create a first deal with daily compounding interest calculation in the system.

The change is coming so you can choose either to embrace it or to postpone it. We decided to embrace it now.

Urszula Chwala, Treasury Lead for LYB

Urszula concludes: “The change is coming so you can choose either to embrace it or to postpone it. We decided to embrace it now. The greatest achievement of this project is that the project was executed within original timelines, without major issues and it gave the whole Treasury team confidence that the system will perform well. What needed to be achieved was really achieved. The complete solution is already implemented for the technical side.”

Royal FloraHolland launched the Floriday digital platform to enhance global flower trade by connecting growers and buyers, offering faster transactions, and streamlining international payment solutions.

In a changing global floriculture market, Royal FloraHolland created a new digital platform where buyers and growers can connect internationally. As part of its strategy to offer better international payment solutions, the cooperative of flower growers decided to look for an international cash management bank.

Royal FloraHolland is a cooperative of flower and plant growers. It connects growers and buyers in the international floriculture industry by offering unique combinations of deal-making, logistics, and financial services. Connecting 5,406 suppliers with 2,458 buyers and offering a solid foundation to all these players, Royal FloraHolland is the largest floriculture marketplace in the world.

The company’s turnover reached EUR 4.8 billion (in 2019) with an operating income of EUR 369 million. Yearly, it trades 12.3 billion flowers and plants, with an average of at least 100k transactions a day.

The floriculture cooperative was established 110 years ago, organizing flower auctions via so-called clock sales. During these sales, flowers were offered for a high price first, which lowered once the clock started ticking. The price went down until one of the buyers pushed the buying button, leaving the other buyers with empty hands.

The Floriday platform

Around twenty years ago, the clock sales model started to change. “The floriculture market is changing to trading that increasingly occurs directly between growers and buyers. Our role is therefore changing too,” Wilco van de Wijnboom, Royal FloraHolland’s manager corporate finance, explains. “What we do now is mainly the financing part – the invoices and the daily collection of payments, for example. Our business has developed both geographically and digitally, so we noticed an increased need for a platform for the global flower trade. We therefore developed a new digital platform called Floriday, which enables us to deliver products faster, fresher and in larger amounts to customers worldwide. It is an innovative B2B platform where growers can make their assortment available worldwide, and customers are able to transact in various ways, both nationally and internationally.”

Our business has developed both geographically and digitally, so we noticed an increased need for a platform for the global flower trade

Wilco van de Wijnboom, Royal FloraHolland’s Manager Corporate Finance

The Floriday platform aims to provide a wider range of services to pay and receive funds in euros but also in other currencies and across different jurisdictions. Since it would help treasury to deal with all payments worldwide, Royal FloraHolland needed an international cash management bank too.

Van de Wijnboom: “It has been a process of a few years. As part of our strategy, we wanted to grow internationally, and it was clear we needed an international bank to do so. At the same time, our commercial department had some leads for flower business from Saudi-Arabia and Kenya. Early in 2020, all developments – from the commercial, digital and financing points of view – came together.”

RFP track record

Royal FloraHolland’s financial department decided to contact Zanders for support. “Selecting a cash management bank is not something we do every day, so we needed support to find the right one,” says Pim Zaalberg, treasury consultant at Royal FloraHolland. “We have been working together with Zanders on several projects since 2010 and know which subject matter expertise they can provide. They previously advised us on the capital structure of the company and led the arranging process of the bank financing of the company in 2017. Furthermore, they assisted in the SWIFT connectivity project, introducing payments-on-behalf-of. They are broadly experienced and have a proven track record in drafting an RFP. They exactly know which questions to ask and what is important, so it was a logical step to ask them to support us in the project lead and the contact with the international banks.”

Zanders consultant Michal Zelazko adds: “We use a standardized bank selection methodology at Zanders, but importantly this can be adjusted to the specific needs of projects and clients. This case contained specific geographical jurisdictions and payment methods with respect to the Floriday platform. Other factors were, among others, pre-payments and the consideration to have a separate entity to ensure the safety of all transactions.”

Strategic partner

The project started in June 2020, a period in which the turnover figures managed to rebound significantly, after the initial fall caused by the corona pandemic. Van de Wijnboom: “The impact we currently have is on the flowers coming from overseas, for example from Kenya and Ethiopia. The growers there have really had a difficult time, because the number of flights from those countries has decreased heavily. Meanwhile, many people continued to buy flowers when they were in lockdown, to brighten up their new home offices.”

Together with Zanders, Royal FloraHolland drafted the goals and then started selecting the banks they wanted to invite to find out whether they could meet these goals. All questions for the banks about the cooperative's expected turnover, profit and perspectives could be answered positively. Zaalberg explains that the bank for international cash management was also chosen to be a strategic partner for the company: “We did not choose a bank to do only payments, but we needed a bank to think along with us on our international plans and one that offers innovative solutions in the e-commerce area. The bank we chose, Citibank, is now helping us with our international strategy and is able to propose solutions for our future goals.”

The Royal FloraHolland team involved in the selection process now look back confidently on the process and choice. Zaalberg: “We are very proud of the short timelines of this project, starting in June and selecting the bank in September – all done virtually and by phone. It was quite a precedent to do it this way. You have to work with a clear plan and be very strict in presentation and input gathering. I hope it is not the new normal, but it worked well and was quite efficient too. We met banks from Paris and Dublin on the same day without moving from our desks.”

You only have one chance – when choosing an international bank for cash management it will be a collaboration for the next couple of years

Wilco van de Wijnboom, Royal FloraHolland’s Manager Corporate Finance

Van de Wijnboom agrees and stresses the importance of a well-managed process: “You only have one chance – when choosing an international bank for cash management it will be a collaboration for the next couple of years.”

Future plans

The future plans of the company are focused on venturing out to new jurisdictions, specifically in the finance space, to offer more currencies for both growers and buyers. “This could go as far as paying growers in their local currency,” says Zaalberg.

“Now we only use euros and US dollars, but we look at ways to accommodate payments in other currencies too. We look at our cash pool structure too. We made sure that, in the RFP, we asked the banks whether they could provide cash pooling in a way that was able to use more currencies. We started simple but have chosen the bank that can support more complex setups of cash management structures as well.” Zelazko adds: “It is an ambitious goal but very much in line with what we see in other companies.”

Also, in the longer term, Royal FloraHolland is considering connecting the Floriday platform to its treasury management system. Van de Wijnboom: “Currently, these two systems are not directly connected, but we could do this in the future. When we had the selection interviews with the banks, we discussed the prepayments situation - how do we make sure that the platform is immediately updated when there is a prepayment? If it is not connected, someone needs to take care of the reconciliation.”

There are some new markets and trade lanes to enter, as Van de Wijnboom concludes: ”We now see some trade lanes between Kenya and The Middle East. The flower farmers indicate that we can play an intermediate role if it is at low costs and if payments occur in US dollars. So, it helps us to have an international cash management bank that can easily do the transactions in US dollars.”

Two ING experts share their views on deposit modeling.

The low interest rate environment has faced banks with structural changes in customer behavior and converging products such as savings and current accounts. ING, one of Europe’s largest players in the savings market and a long-term client of Zanders, has positioned itself as one of the frontrunners in this environment. We sat down with Tom Tschirner (head of market risk at ING Germany) and Maarten Hummel (financial risk officer at ING Group) to gather their view on modeling and balance sheet management after these structural shifts.

In some European countries, savings rates appear to have hit a limit where they have stayed at a low level for a few years, despite interest rates moving down. This would suggest a structural shift where the relation between interest rates and savings rates has broken down. How can banks model savings in this unprecedented situation?

Tom Tschirner: “The situation is different everywhere. Within the countries where we are active, the legal and regulatory frameworks are very different. For example, in countries like Italy or Belgium, the law prohibits further decreases in specific interest rates. In Germany, this regulatory restriction is not in place. From a modeling perspective, this introduces a very different dynamic.”

Maarten Hummel: “It seems all banks are struggling with the impact of these low interest rates on the behavior of their customers. There is no real history on these low rates to use in our modeling. To develop forward-looking scenarios and to know how to model these scenarios we therefore work even more closely with the business.”

How do you weigh these expert opinions in unprecedented scenarios versus historic observations?

Tschirner: “The political wind is towards using historic data. It is challenging to substantiate the basis for your expert opinion towards a regulator. Using data-based model decisions is more straightforward from that point of view, as the model is then objectively determined. However, there are situations like the one we have now, when you just have no or very limited data. And then you must use expert judgement.

The question is then: how good can the experts be? We neither have data nor experience with the current situation. What becomes important in that situation is not to do stupid things. It’s important to know what competitors are doing. For example, if you find out that on average their deposits are modeled for the duration of three years and your own model indicates you should use seven years, you should take a break and reconsider. Particularly when you don’t have enough data and experience.”

What is your role in this as a market risk manager?

Tschirner: “Our role is always to make sure that common sense is around the table and that everyone who is somehow affected by the model knows how much it depends on expert opinion, data, competition and common sense.”

Hummel: “We always have to be sure that we understand and can explain the dynamics in the forward-looking scenarios; how the bank reacts, how the clients react, what would happen in the wider savings market and other relevant factors. There needs to be a logic to explain the scenario outcomes, both on the savings portfolio and the overall balance sheet. We always look at what it means for the bank as a whole, for example: how would we manage the total bank in such a situation? It is not just a simple exercise of running a savings model based on historic data to get the answers – more important is that you assess the overall plausibility. Therefore, when calibrating our savings models, we now spend more time discussing the scenarios in-depth with the various stakeholders in the bank."

Does that mean that both quantitative and qualitative elements are discussed?

Hummel: “The business strategy is leading. We use a global framework for our business strategy to look at how it would play out in a certain environment. Then you need to have discussions on whether that strategy will really hold in the more severe scenarios. We do take scenarios into account in a more qualitative strategy discussion. We have to look at the market, our own balance sheet and how we are positioned. It is an interesting discussion.”

There is no real history on rates below zero.

Maarten Hummel, Financial Risk Officer at ING Group

To what extent do you look at the restrictions on the lending side in discussions on savings modeling?

Hummel: “The starting point is to look at the saving portfolio independently, but at some stage you cannot escape the rest of the balance sheet. For example, if I have a 50-year liability, where am I going to invest it and what is my funding value? There needs to be a check to see if the value attached to it exists.”

Tschirner: “At the end of the day, when it comes to modeling savings, the question that we are trying to answer is: how should we invest the money that we get from our clients? And can you do that totally independently of the asset situation? Most likely not. If the model tells you to invest the money for fifty years, but there are no such assets in the economy, the model is not very helpful. I would not say it is the individual situation of the bank that matters, but more the economy or the country. How easy is it to find long-term assets in Germany, Poland, or Belgium? That certainly plays an important role for the modeling of savings. One year ago, I may not have subscribed to this view, but now I’m quite convinced about that.”

Do the low savings rates impact the relation between the balances on payment accounts and the saving accounts?

Hummel: “Before, the idea was that these have different functions; one for the transactions and one to earn interest. The incentive on the savings side has now largely disappeared. Inevitably, we see many more funds staying on the current account. The question is then: how can you separate the two parts? The client does not bother to put it on the savings account, because the interest is the same. But since we have to be prepared for a scenario where interest rates will go up significantly again, we keep identifying that money as savings. You need data to identify the amount of transactional account money and separate that from the savings amount. Rates have been low for a long period already, so for a newly started bank estimating that will be very hard.”

A large portion of German ING clients is relatively new. Is it therefore harder to get the right data?

Tschirner: “There are different ways to look at it, but what we clearly observe is that the average balance of the current accounts is increasing quite significantly. You can relook at history and try to find a trend, to see what the average balances would be if it were not for the low-rate environment. Or you can look at intra-monthly patterns, driven for example by salaries and rents. If there is a threshold above which you do not find a pattern anymore, then it looks more like a savings account. These are two approaches to determine which part should be modeled as true current account money and which part as savings. There is no standard yet, but given the regulatory attention, we will find an industry standard in the coming year.”

You need data to identify the amount of transactional account money and separate that from the savings amount.

Tom Tschirner, Head of Market Risk at ING Germany

Do you think it is a common blind spot that the segmentation between those two is often not explicitly modeled?

Tschirner: “It’s not the biggest issue that we have. But yes, you need a model. If you want a real good model though, you need all legs of the cycle; you would also need an observation from a point in time that rates increase – and you don’t have that.”

Hummel: “I agree, you need a full cycle. The challenge is that for each solution you put on this, you need an exit strategy, so once savings rates go up again and market rates are high, you gradually build down the savings on your current account. In the meantime, every client is different. We have different sets of clients and you need to have data on how your client composition is changing over time.”

Tschirner: “In Germany, ING is growing, and the number of accounts has been increasing a lot. We also know that the average age of our clients has gone up. You could argue that older clients intend to have higher balances on their accounts and that they do not shift it when rates are around zero. But if you look at data, you will not be able to tell the difference. And there is no data-based way of telling this apart. That makes it challenging to model.”

Zanders & Savings modeling: Zanders has supported many European banks in the development, validation and outsourcing of risk models for non-maturing deposits. We offer support through the entire modeling cycle on topics such as: Calibration of models based on historical data and expert judgement, Substantiation of your model methodology and key assumptions, Continuous model updates on recent market or portfolio developments, The in-house developed Savings Modeling Solution services banks digitally on non-maturing deposits risk modeling and management using efficient calibration, state of the art tooling and longstanding subject-matter expertise.

Martijn Habing, head of Model Risk Management (MoRM) at ABN AMRO bank, spoke at the Zanders Risk Management Seminar about the extent to which a model can predict the impact of an event.

The MoRM division of ABN AMRO comprises around 45 people. What are the crucial conditions to run the department efficiently?

Habing: “Since the beginning of 2019, we have been divided into teams with clear responsibilities, enabling us to work more efficiently as a model risk management component. Previously, all questions from the ECB or other regulators were taken care of by the experts of credit risk, but now we have a separate team ready to focus on all non-quantitative matters. This reduces the workload on the experts who really need to deal with the mathematical models. The second thing we have done is to make a stronger distinction between the existing models and the new projects that we need to run. Major projects include the Definition of default and the introduction of IFRS 9. In the past, these kinds of projects were carried out by people who actually had to do the credit models. By having separate teams for this, we can scale more easily to the new projects – that works well.”What exactly is the definition of a model within your department? Are they only risk models, or are hedge accounting or pricing models in scope too?

“We aim to identify the widest range of models as possible, both in size and type. From an administrative point of view, we can easily do 600 to 700 models. But with such a number, we can't validate them all in the same degree of depth. We therefore try to get everything in picture, but this varies per model what we look at.”

To what extent does the business determine whether a validation model is presented?

“We want to have all models in view. Then the question is: how do you get a complete overview? How do you know what models there are if you don't see them all? We try to set this up in two ways. On the one hand, we do this by connecting to the change risk assessment process. We have an operational risk department that looks at the entire bank in cycles of approximately three years. We work with operational risk and explain to them what they need to look out for, what ‘a model’ is according to us and what risks it can contain. On the other hand, we take a top-down approach, setting the model owner at the highest possible level. For example, the director of mortgages must confirm for all processes in his business that the models have been well developed, and the documentation is in order and validated. So, we're trying to get a view on that from the top of the organization. We do have the vast majority of all models in the picture.”

Does this ever lead to discussion?

“Yes, that definitely happens. In the bank's policy, we’ve explained that we make the final judgment on whether something is a model. If we believe that a risk is being taken with a model, we indicate that something needs to be changed.”

Some of the models will likely be implemented through vendor systems. How do you deal with that in terms of validation?

“The regulations are clear about this: as a bank, you need to fully understand all your models. We have developed a vast majority of the models internally. In addition, we have market systems for which large platforms have been created by external parties. So, we are certainly also looking at these vendor systems, but they require a different approach. With these models you look at how you parametrize – which test should be done with it exactly? The control capabilities of these systems are very different. We're therefore looking at them, but they have other points of interest. For example, we perform shadow calculations to validate the results.”

How do you include the more qualitative elements in the validation of a risk model?

“There are models that include a large component from an expert who makes a certain assessment of his expertise based on one or more assumptions. That input comes from the business itself; we don't have it in the models and we can't control it mathematically. At MoRM, we try to capture which assumptions have been made by which experts. Since there is more risk in this, we are making more demands on the process by which the assumptions are made. In addition, the model outcome is generally input for the bank's decision. So, when the model concludes something, the risk associated with the assumptions will always be considered and assessed in a meeting to decide what we actually do as a bank. But there is still a risk in that.”

How do you ensure that the output from models is applied correctly?

“We try to overcome this by the obligation to include the use of the model in the documentation. For example, we have a model for IFRS 9 where we have to indicate that we also use it for stress testing. We know the internal route of the model in the decision-making of the bank. And that's a dynamic process; there are models that are developed and used for other purposes three years later. Validation is therefore much more than a mathematical exercise to see how the numbers fall apart.”

Typically, the approach is to develop first, then validate. Not every model will get a ‘validation stamp’. This can mean that a model is rejected after a large amount of work has been done. How can you prevent this?

“That is indeed a concrete problem. There are cases where a lot of work has been put into the development of a new model that was rejected at the last minute. That's a shame as a company. On the one hand, as a validation department, you have to remain independent. On the other hand, you have to be able to work efficiently in a chain. These points can be contradictory, so we try to live up to both by looking at the assumptions of modeling at an early stage. In our Model Life Cycle we have described that when developing models, the modeler or owner has to report to the committee that determines whether something can or can’t. They study both the technical and the business side. Validation can therefore play a purer role in determining whether or not something is technically good.”

To be able to better determine the impact of risks, models are becoming increasingly complex. Machine learning seems to be a solution to manage this, to what extent can it?

“As a human being, we can’t judge datasets of a certain size – you then need statistical models and summaries. We talk a lot about machine learning and its regulatory requirements, particularly with our operational risk department. We then also look at situations in which the algorithm decides. The requirements are clearly formulated, but implementation is more difficult – after all, a decision must always be explainable. So, in the end it is people who make the decisions and therefore control the buttons.”

To what extent does the use of machine learning models lead to validation issues?

“Seventy to eighty percent of what we model and validate within the bank is bound by regulation – you can't apply machine learning to that. The kind of machine learning that is emerging now is much more on the business side – how do you find better customers, how do you get cross-selling? You need a framework for that; if you have a new machine learning model, what risks do you see in it and what can you do about it? How do you make sure your model follows the rules? For example, there is a rule that you can't refuse mortgages based on someone's zip code, and in the traditional models that’s well in sight. However, with machine learning, you don't really see what's going on ‘under the hood’. That's a new risk type that we need to include in our frameworks. Another application is that we use our own machine learning models as challenger models for those we get delivered from modeling. This way we can see whether it results in the same or other drivers, or we get more information from the data than the modelers can extract.”

How important is documentation in this?

“Very important. From a validation point of view, it’s always action point number one for all models. It’s part of the checklist, even before a model can be validated by us at all. We have to check on it and be strict about it. But particularly with the bigger models and lending, the usefulness and need for documentation is permeated.”

Finally, what makes it so much fun to work in the field of model risk management?

“The role of data and models in the financial industry is increasing. It's not always rewarding; we need to point out where things go wrong – in that sense we are the dentist of the company. There is a risk that we’re driven too much by statistics and data. That's why we challenge our people to talk to the business and to think strategically. At the same time, many risks are still managed insufficiently – it requires more structure than we have now. For model risk management, I have a clear idea of what we need to do to make it stronger in the future. And that's a great challenge.”

Fast-growing technological developments are accelerating the pace of change for treasury. Zanders and Citi have produced a whitepaper that reflects perspectives on the future of corporate treasury. Ron Chakravarti, Citi’s global head of treasury advisory, and Zanders partner Laurens Tijdhof discuss some of the key themes.

What are the main changes influencing treasury’s added value within corporates?

Laurens Tijdhof (LT): “Business models are changing. In the decades since the introduction of the internet, ‘digital natives’ - new multinational companies such as Uber and Google - have emerged to disrupt all industry sectors. These companies have less legacy than traditional multinationals. Treasury plays an important role in that digital native environment, for example with payment innovation in ecommerce. Traditional multinationals are typically dealing with a lot of legacy because of mergers and acquisitions throughout their history. For them, the change is more transformational in nature, as they are doing something different than they have done in the past decades or even in the past century. This is one of the elements where treasury can add significant value; to understand from a financial point of view where the business is in the current cycle and to see what things need to be changed, updated or optimized to add value.”

Ron Chakravarti (RC): “Firstly, the pace of change in commerce has picked up, driven by new technologies and new ways of doing business. These are shifting the timing, value, and volume of cash flows and, of course, that impacts treasury. Secondly, while treasury always has to manage regulations and the cash flow impact of changes in global taxation, the pace of change in these have also picked up. Finally, geopolitical uncertainty has created additional considerations at this point in time. Corporate treasurers, therefore, need to ensure their teams are increasingly nimble to deal with all of these issues. The good news is that the availability of new technologies, data and artificial intelligence have the potential to change how treasury works and to create added value.”

At which point are companies ready for new technology?

LT: “Before a company can enter the next stage of treasury maturity, it first needs to get the basics right. This means having a focus on centralization, standardization and automation, typically using traditional technology like a TMS or an ERP system. And if you have these systems in place, be sure you’re using and benefiting them optimally from that environment first. Once you have the basics right, you can go to the next stage of a smart treasury, using the new digital or exponential technologies. Then you can benefit from the good basis and use more of the data in analytical ways, with algorithms or newer technologies like robotic process automation (RPA) or artificial intelligence (AI).”

RC: “I completely agree that getting the basics right, by completing the journey to an efficient treasury comes first. Treasury is on an evolution path of becoming first efficient, then smart, and finally integrated. Getting to efficient means that you must standardize, centralize, and automate. Even among multinational companies, not all have mature, centralized treasury models. Getting to a best in class model is key. In most industries that includes a functionally centralized regionally distributed treasury model, with operational treasury on a common infrastructure and processes. Once you are substantially there, you can work on the next step change, in making the move to a smart treasury. And ultimately to an integrated treasury.”

How should a treasurer deal with the continuous change driven by these exponential technologies?

RC: “Well, an issue is that – as The Future of Treasury whitepaper indicates - only 14 percent of corporates have a digital strategy at the treasury level. Why is this so low? One reason is the availability of the right resources. While treasurers have previously adapted to technology change, this change is all happening a lot faster now - for treasury and the broader business. Ultimately, treasury is all about information. Today, more than ever, the treasury function needs to include people who are technologically savvy. People who are able to comprehend what is changing and how to best deploy technology. That will become increasingly important to create value for the business. Treasury teams recognize that they need to have a digital strategy, but many of them are not fully equipped to define one. They are looking for help from industry leaders with a treasury framework to define their digital treasury strategy. That is one of the reasons for this collaboration between Citi and Zanders; in many cases we recognize that we can better do it together, creating added value for our mutual clients.”

LT: “If you compare the current situation to ten years ago, a treasurer would only buy new technology if there was a real requirement. Today, there’s new technology that many treasurers do not fully understand – in terms of what problems it could potentially solve for the company. What you often see now is that treasurers start with small projects, proofs of concepts, to test some innovative ideas. You can compare it with the iPhone; when Steve Jobs invented it, it took some time before people really understood what to do with it, what value it would add in their life. First you need to see what it is, what it can do for you, whether it can solve a real problem. That’s the exiting stage in which we are now. Some treasurers are trail blazers, others are more followers that first want to learn from others about how it has brought them forward.”

Where can these latest technologies really improve treasury? Are there any issues they cannot solve?

LT: “Treasury is all about information and data. There’s a lot of information available in a treasury environment and you sometimes need new technologies and standardized processes to unlock the value out of these data. Treasury covers a large amount of structured data in all kinds of systems. If you want to translate that data insight into valuable conclusions, then technology is probably the right enabler to help; with data analytics and visualization, for example. But, if you don’t have your data centrally available in a data warehouse or data lake, then that’s the first part you should work on; you first need to have your data centrally available to be able to do something with it. Unfortunately, many large multinational companies are still in that stage, they still have data that’s very fragmented and decentralized. For those companies, you could say that the newest technologies have come too early.”

RC: “What will improve treasury? We should first consider what treasurers are seeking to do. Today, we are seeing an increasing appetite from corporate treasurers for integrated decision support tools going beyond what treasury management systems can provide. To that end, we at Citi are running a number of experiments, collaborating with our clients and fintechs, and enabling our clients’ journey towards smart treasury. This is about moving beyond descriptive analytics to decision support and decision automation, and offering opportunity to realize the full automation of operational treasury. What won’t be solved? Well, we won’t get there in 2020 but we will certainly soon start seeing the foundational steps in this transition to a fully automated operational treasury and that’s what is so exciting.”

Switzerland’s Swiss Re is the world’s second largest provider of reinsurance and insurance-related risk products.

Traditionally the company insures events that can lead to huge losses, such as natural disasters. Two years ago, this reinsurer decided to further strengthen its payment processes. Swiss Re has engaged the support of Zanders, in several areas, since 2012. At first, this was mainly related to Group Treasury’s balance sheet management and risk reporting processes. Among others, a new liquidity risk measurement and reporting system was put in place using a combination of an in-house built data warehouse, a vendor risk management system and modern business intelligence (BI) technology.

Connectivity ‘on par’

At the time, account manager Jeroen van der Heide was already Group Treasury’s main point of contact. “Since 2017, we’ve also been helping Swiss Re to improve their operational treasury processes,” Van der Heide says. In early 2017, the reinsurer organized several workshops on bank connectivity. “We participated in those workshops and provided our point of view assessment on their as-is. Swiss Re’s connectivity demonstrated to be ‘on par’ with the market standard. However, our other feedback during those workshops strengthened their resolve to work towards a new central financial messaging hub in the medium term. We were chosen to support them in the realization of that ambition.”

Single source of truth

A central financial messaging hub is a considerable undertaking, given that the company has at least a dozen different systems from which payments are initiated and where bank statements are consumed. Like many big financial multinationals, Swiss Re has grown substantially over the years, partially through acquisitions. One of Zanders’ first tasks was to analyze the presence of bank account information in the various systems – and the consistencies and inconsistencies between them. This analysis then served as the basis for a blueprint of the 'to be' data model.

It’s crucial to designate a single source of truth for different types of master data, simply because that avoids getting stuck in master data reconciliation, it really is the starting point for any move towards operational excellence.

Nicolas Andres, head of Group Finance Transformation at Swiss Re

SWIFT network

In the fall of 2017, the focus shifted to connectivity with the SWIFT network. Zanders made sure that compliance with the Customer Security Programme (CSP) was achieved without problems and, with an eye on improving business continuity, an initial analysis was carried out on the SWIFT Alliance Lifeline program. Then it was time to support the switchover to a new SWIFT Service Bureau (SSB). Zanders provided both the project management and subject matter expertise to support the requirements analysis, drafted the RfP document and guided the selection process towards choosing a new SSB. Throughout this process, special consideration was given to complementary services, which a new hub could benefit from. Andres explains: “As the single exit point towards the wider financial system, the hub is naturally well-suited for complementary controls, for example to detect payment fraud.”

Feasibility study

On this topic, Zanders was asked to assess the benefit of leveraging modern machine learning techniques on the traffic to and from the SSB gateway. “Nowadays, advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence receive attention nearly on a daily basis,” says Van der Heide. “Vendors have been quick to take advantage of this development, and they promise a lot.” Andres continues: “We were curious to what extent these techniques would actually bring us forward. We know Zanders prefers to segregate hype from benefit. Plus they’re well acquainted with our infrastructure and have relevant experience from their risk advisory practice, so they were the natural partner to ask this question.”

Zanders' advice on what to do next, and particularly on what not to do, was totally appropriate.

Nicolas Andres, head of Group Finance Transformation at Swiss Re

Electronic banking tools

Meanwhile, as the SSB selection project slowly drew to a conclusion, an analysis was made of the various electronic banking tools that had worked their way into the organization over the years. “The analysis was an important step in the preparation process for the financial messaging hub. It turned out there were quite a few more tools in use than expected.” concedes Andres. “The vast majority are actually only used to collect statements from individual banking partners. That confirmed our viewpoint that proper bank statement distribution would be an important feature of the new 'to be' solution.”

Webservice-centric approach

At the start of 2019, the implementation of the new financial messaging hub finally kicked off. “An important benefit of the 'to be' solution is that we move from a batch-centric approach to a webservice-centric approach. This means that upstream systems can basically deliver their messages whenever they want,” says Andres. The first step of the project includes implementing the switchover to the new SSB, finding an adequate compliance-filtering solution, rationalizing the Bank Identifier Codes (BICs), implementing the SWIFT Alliance Lifeline and putting the first REST APIs in place. Two years later, Zanders is still involved, coordinating progress surrounding the six workflows and ensuring that all stakeholders are adequately involved.

Trust

When asked what makes the collaboration work, Andres says: “I believe in resourceful and intelligent junior consultants, supported by pragmatic experts where needed. Zanders offers both.” Jeroen feels the relationship is largely built on trust – and that is something that works both ways. “Nicolas trusts me on the quality we provide. That is something I am proud of and we are pulling out all the stops to ensure we continue to justify that.” Andres summarizes: “It is the engagement and skill shown to get the job done after the initial Powerpoints that convinces.”