WACC: Practical Guide for Strategic Decision- Making – Part 2

Creating Shareholder Value – Towards an Optimal Credit Rating

The second article in this series on WACC discusses why the credit rating should not be a goal in itself, but the result of the corporate objective to maximize value for shareholders and other stakeholders. It elaborates on managing the WACC and creating shareholder value, which is the main focus of strategic decision-making.

The article describes the relationship between the WACC, shareholder value and the existence of an optimal credit rating.

Credit Rating Policy

Newton’s first law of motion states that objects ‘tend to keep on doing what they are doing’. In fact, it is the natural tendency of objects to resist changes in their state of motion. This resistance to change is also known as inertia. Many companies have the tendency to maximize their credit rating towards a triple-A rating in order to minimize their cost of debt.

Generally, however, this policy does not minimize the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). Therefore, these companies have the opportunity to stop this inertia and increase shareholder value as a result.

Market evidence shows that, in recent years, fewer companies have received a triple-A credit rating and there are several reasons for this:

- More tolerance of risk

- Company-specific challenges

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Regulatory concerns

- New industry dynamics

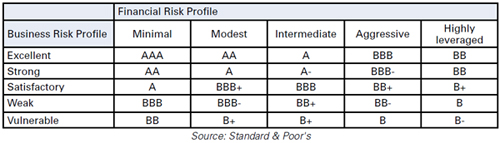

This article discusses the concept that the optimal credit rating for companies is not always the highest rating. Credit ratings give information about the probability of default and the size of loss when a company defaults (recovery ratio). Therefore a credit rating gives an indication about the downside risk of debt and not about the upside potential of equity. There is a great misunderstanding about the corporate’s objective with respect to credit ratings. The table below provides insight into the relationship between business risk, financial risk and credit ratings.

A triple-A credit rating might seem ideal but it actually indicates that a company bears relatively low risk. For a company that does not invest in highrisk projects, or for a company with low leverage, it is relatively easy to get a triple-A rating. Is this an indication of good performance? Not really, maybe a triple-A credit rating is the result of a lack of creativity.

Risk is inherent in running a company therefore the credit rating should not be a goal in itself but the result of the corporate objective to maximize value for shareholders and other stakeholders.

Corporate Finance Dilemma

For most companies, corporate finance is a tradeoff process between raising debt, common equity and hybrid capital. The availability of different types of capital creates a dilemma for these companies.

In general terms, debt is advantageous because of its low costs and tax deductibility but it can be disadvantageous where bankruptcy costs are concerned. More debt increases the default risk of a company and therefore shareholders will require a higher return on equity. Furthermore, a company can also raise hybrid capital, which contains elements of both debt and equity. But the impact of hybrids on the WACC and shareholder value differs, depending on the treatment by tax authorities, accountants and rating agencies. Ultimately, the optimal capital structure of a company will normally consist of a mixture of debt, common equity and hybrid capital.

Designing such a capital structure is based on a combination of two elements:

- The level of debt-to-equity.

- The mixture of financing instruments.

Optimal Level of Debt-to-Equity

Companies should focus on the optimal level of debt-to-equity, also known as leverage. Best market practice is to define a target capital structure and to combine this objective with maintaining sufficient financial flexibility to cope with adverse scenarios.

Companies with stable cash flows and low risk profiles can generally absorb more debt into their balance sheets than other types of companies. To define the optimal capital structure, however, an analysis is required that examines how the perceptions of investors, rating agencies and financial markets in general are affected by capital structure changes. In assessing an optimal capital structure it is important to focus not only on base case scenarios but also on downside scenarios, which means that an optimal capital structure will allow for unused borrowing capacity. This enables the corporate to increase debt in adverse circumstances, e.g. the possibility that capital expenditure may be substantially above base case scenarios. An example of unused borrowing capacity could be contingent capital, such as a standby credit facility.

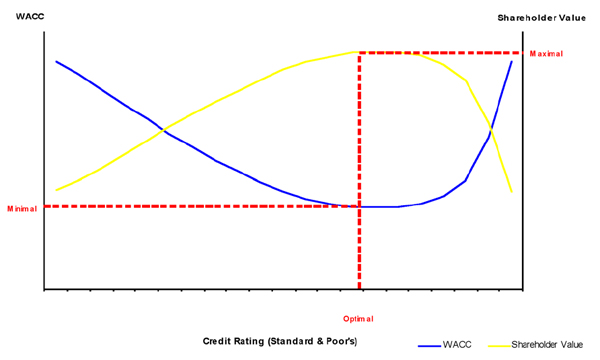

The graph shows the progress of the WACC as well as the market value of a company. The flat bottom of the WACC graph clearly shows that there is a relatively large range where the level of debt to- equity is maximizing shareholder value. This indicates that the optimal credit rating of a company exists within this area. It is important to mention that every company has its own optimal range. The definition of an optimal credit rating is based on the following considerations:

- Minimum WACC: The credit rating should not be a goal in itself, but the result of the corporate objective to maximize value for shareholders and other stakeholders. Therefore an optimal credit rating is located in the range where the level of debtto- equity minimizes the WACC. This is also displayed in the graph above.

- Meeting financial covenants: Financial covenants provide creditors with a warning about deteriorating financial conditions and give them the ability to influence the borrower under these conditions. A number of companies have financial covenants to maintain investment grade status. It is likely that these covenants will increase the credit spread on debt when the credit rating is close to minimum investment grade.

- Protection against adverse scenarios: An optimal credit rating will allow a company enough unused borrowing capacity so that during times of adversity it can use this capacity. In particular, it is important that financial projections under adverse scenarios remain consistent with investment grade status and hence continue to allow a company to finance its functions.

- Protection against turbulent market conditions: Access to capital markets may be difficult during turbulent market conditions if companies are rated at BBB and below. Credit spreads typically widen under adverse economic conditions as investor quality consciousness and ‘flight to quality’ increase.

Maintenance of an optimal credit rating will reduce the risk that companies will be unable to attract necessary finance at reasonable rates.

Optimal Mixture of Financing Instruments

When the optimal level of debt-to-equity is defined, companies should focus on the optimal mixture of financing instruments, including:

- Interest-bearing debt: When raising interestbearing debt, a company can generally choose between bank debt, private debt and public debt. Best market practice is to match cash flows on debt as closely as possible with cash flows that the company makes on its assets. By doing so, a company reduces default risk and it increases the debt capacity. Furthermore, it increases shareholder value because of lower earnings volatility.

- Common equity: A popular statement is ‘equity is a cushion, debt is a sword’. While debt with its fixed payment character disciplines managers, equity should give them more flexibility because of the lack of a fixed return. However, stock markets can discipline managers as well. A good example is the recent trend of hostile takeovers of underperforming public companies by private equity firms.

- Hybrid capital: Hybrids contain elements of debt and equity, e.g. preferred equity, convertible bonds and subordinated debt. The perfect hybrid instrument will have all of the tax advantages of debt, while preserving the flexibility offered by equity. A company must ensure that it has not crossed the line drawn by tax authorities though. It is a waste of effort if the instrument that is designed does not deliver the tax benefits intended.

The overall objective when designing the optimal mixture of financing instruments is to keep investors, rating agencies and financial markets satisfied. Bondholders and ratings agencies want companies to issue equity because it makes them safer. Shareholders do not want companies to issue more equity because it dilutes earnings per share.

Financial covenants ensure that companies meet their requirements in terms of capital ratios, usually defined in book value. Financing that leaves all stakeholders happy is the ultimate goal.

Best market practice is not to lock in market ‘mistakes’ that work against a company. For example, rating agencies could under-rate a company (credit rating gap), or financial markets could under-price stocks or bonds (value gap). If this occurs, companies should not lock in these gaps by issuing financing instruments for the long-term. In particular, when equity is underpriced, issuing equity or equity-based products (including convertibles) would transfer wealth from existing to new shareholders.

Furthermore, issuing long-term debt when a company is under-rated locks in interest rates at levels that are too high, given the actual default risk. Therefore solving potential gaps requires good communication with investors or rating agencies. This can be done based on in-depth financial analysis that examines how the perceptions of investors, rating agencies and financial markets in general are affected by capital structure changes.

In assessing a capital structure it is important to focus not only on base case scenarios but also on downside scenarios.

Corporate Case Studies on Capital Structure and Credit Rating

The following section contains case studies on the policy of two companies, KPN Telecom and Nestlé, with respect to their capital structure and credit rating.

KPN Telecom: Series of Downgradings

Highly leveraged companies could face a series of downgradings. A good example is the situation that occurred several years ago with the Dutch listed company, KPN Telecom. The telecoms market was bullish for a long time but expectations had started to diminish. It was doubtful whether the expected growth could be realized or whether the high capital expenditures for UMTS (the 3G mobile system) could provide a profitable return.

Rating agencies, such as Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s, picked up on this market signal and downgraded several telecom companies and, as a consequence, the interest expenses of those companies increased. The highly leveraged companies, such as KPN Telecom, directly faced financial problems and therefore rating agencies further downgraded these companies. The interest expenses further increased and so did the financial problems.

In just three years, KPN Telecom was downgraded several times. From AA in September 2000, its rating reached the lowest level of BBB- at the end of 2002. This was also the end of the series of downgradings. From September 2002, KPN Telecom was able to improve its credit rating from BBB- to A- by reducing its debt level and by divesting noncore activities.

At the beginning of February 2006, it decided to increase its leverage again because it felt the pressure of a potential hostile take over by a group of private equity firms. In this group’s opinion, KPN Telecom was too conservatively financed. The additional debt that was raised would be used to finance share repurchases and potential acquisitions.

After the announcement of increasing leverage, KPN Telecom was immediately downgraded from A- to BBB+. Shareholders did reward the revised financing policy with an increase of the stock price by 6.4 per cent though.

Nestlé: Highest or Optimal Credit Rating?

In September 2005, Swiss company Nestlé considered whether it should go for the highest or optimal credit rating. The triple-A rated company, therefore, performed an analysis of its capital structure and concluded that the WACC could be decreased from 7.6 to 7.4 per cent by changing the level of debt-toequity from 10 towards 30 to 35 per cent.1 However, Nestlé decided not to change its capital structure and it is interesting to find out what influenced this decision.

One of the main reasons Nestlé gave was that with a triple-A rating debt can be raised on better terms and conditions. Furthermore, Nestlé wanted to maintain maximum financial flexibility for potential acquisitions. Of course, the cost of debt is lower with a triple-A rating, however, in this situation it is likely that the company does not optimally benefit from the tax deductibility of debt financing. It is also likely that some interesting investment projects would be declined because of a too low risk tolerance.

Nestlé chose not to change its credit rating policy, although it acknowledged the potential benefits of a lower, optimal credit rating. These potential benefits can be quantified. Nestlé could add about €1.5bn shareholder value if it further optimize its capital structure.2 This can be assumed as its accepted costs for maintaining maximum financial flexibility.

Roadmap to an Optimal Credit Rating

The roadmap to an optimal capital structure and credit rating can be defined as follows:

- Start with a scenario analysis of the cash flows through an intuitive or quantitative approach. Intuitively, by analyzing the growth potential of a company, the cyclicality of the cash flows and specific factors that determine the cash flows. For companies with substantial operating history, it can be quantified how sensitive company value and operating income have been to changes in macroeconomic variables, such as inflation, interest rates and exchange rates.

- Best market practice is to define a target capital structure and to combine this objective with maintaining sufficient financial flexibility to cope with adverse scenarios. When the optimal level of debt-to-equity is defined, companies should focus on the optimal mixture of financing instruments, including debt, equity and hybrid capital.

- The optimal capital structure and credit rating is achieved when the WACC is minimized. However, it is relevant to combine this objective with meeting financial covenants and by protecting against adverse scenarios and turbulent market conditions.

Companies located at the right side of the optimal range should be focusing on reducing their debt position and therefore avoiding a series of downgradings. For example, KPN Telecom mainly improved its credit rating from BBB- to A- by reducing its debt level and by divesting non-core activities.

Companies located at the left side of the optimal range could increase their leverage by raising more debt or reducing their equity position. The latter can be realized with share repurchases or distribution of super dividends. Furthermore, these companies could reduce the WACC by investing in more risky projects that add shareholder value.

The highest possible credit rating is not always the best option. Maximizing value for shareholders and other stakeholders can be realized with an optimal level of debt-to-equity, including a mixture of debt, common equity and hybrid capital. As a result, the credit rating will be optimal.

Conclusion

This article has elaborated on the relationship between the WACC, shareholder value and credit ratings. Some companies may have valid reasons to choose a triple-A rating. Nestlé, for example, has clearly thought about the issue and has chosen a sub-optimal WACC. It is important, however, that companies understand and think about the tradeoff between the WACC, shareholder value and credit ratings. In that way, a rational decision can be made about the optimal capital structure of a company.

This decision should be made with an open mind with regard to changes in the capital structure. If there is any irrational resistance to change, then it’s time for the company to end this inertia.

1 Focusing on the drivers of value, www.ir.nestle.com

2 This calculation is based on an operational cash flow of €4.3bn in 2004.