This article explores how newly established treasury functions can lay foundations and go beyond day 1 readiness to establish effective, scalable, and resilient cash and liquidity management for the group, representing a critical lever for long-term financial stability and value creation of the business.

Introduction

In the previous article, From Day 1 to Strategic Partner: Building a Treasury Function for a Carved-Out Business, we highlighted the importance of a tailored target operating model (TOM) to establish a solid strategic and organizational base for the new treasury. Following the definition of the treasury TOM and once day 1 readiness measures are in place, the next priority is to focus on value creation via cash and liquidity management, which represent another key pillar for a successful treasury implementation and treasury process. Cash and liquidity capabilities play a vital role in ensuring treasury delivers both operational continuity and strategic value. This article outlines how to build that foundation by establishing robust and forward-looking cash and liquidity management processes already at the time of the transaction, addressing immediate post-transaction needs, and enabling mid-term process efficiency.

Prepare for Day 1: Managing Liquidity Readiness

When preparing for the closing of an M&A transaction, treasury plays a critical role in ensuring that the new organization operates independently from Day 1. Liquidity planning is essential as cash pressures often peak around the time of legal close.

The following aspects may erase cash reserves if not properly anticipated:

- Upfront costs (transaction fees, legal, advisory, integration).

- Debt financing frameworks still under negotiation.

- Cash repatriation constraints or internal investment requirements to support the separation.

Hence, treasury must address these topics in cash and liquidity planning by:

- Modeling short-term needs under multiple scenarios based on validated assumptions on the business’ structure and liquidity needs.

- Ensuring cash visibility and centralization of cash, where possible to manage funding efficiently.

- Evaluating working capital buffers and the need for interim funding lines.

By addressing these topics before closing, the new entity enters day 1 with visibility on liquidity positions, funding plans, and confidence in its ability to operate independently.

Manage Day 1: Establishing Control, Visibility and Centralization

For a newly independent entity, cash visibility is often fragmented across systems and bank accounts, especially in the early stages after a carve-out. Yet gaining (real-time) transparency is fundamental to effective cash management and decision-making. The foundational elements to achieve at this stage are:

- Set up efficient connectivity with all banking partners.

- Deploy treasury technology (e.g., a TMS or interim solution) to aggregate bank balances and transactions centrally.

- Implement daily cash positioning processes across all relevant bank accounts.

- Define responsibilities and control mechanisms for cash operations, ensuring a clear RACI model.

Cash visibility improves control and reduces risk while enabling better liquidity allocation across the group via a centralized cash management process. The deployment of cash concentration structures, such as cash pooling, allows the unlocking of financial resources and benefits, such as fee reduction or interest optimization. Furthermore, centralized cash management data is a prerequisite for AI-driven cash applications and greater financial risk exposure definition1, which can significantly reduce manual effort in distributing and managing cash across the group.

Early Stabilization: Forecasting and Short-Term Control

Once operational continuity is secured, the focus should move to stabilizing cash and liquidity processes.

Forecasting in a post-carve-out environment is challenging, yet essential. Missing historical data, unclear transaction volumes, and transitional arrangements (e.g., TSAs) often reduce forecast accuracy.

A suitable solution is the deployment of a layered forecasting approach, including:

- Short-term cash flow forecasts (typically 13-week rolling) to guide immediate liquidity needs.

- Medium-term liquidity planning, integrated with business planning (FP&A) and CAPEX cycles.

- Stress-testing and scenario analysis to evaluate performance under simulated business conditions.

In our experience, cash forecasting is an evolving process, which can be optimized and automated over-time through data integration (e.g. from ERP system) and predictive modeling. With data quality as the foundation, cash flow forecasting can begin by establishing the most accurate starting point and committed forecasts under company control, such as opening balances and invoice payables. Once the high-certainty inputs are captured, additional cash flows such as committed accounts receivable and other material forecasts e.g. sales forecast or CAPEX forecast can be integrated.

Carved-out entities must consider the growing maturity and quality of their systems and respective data over the first 12 months after day 1.

Designing a Fit-for-Purpose Liquidity Structure

Once visibility and forecasting are addressed, the focus should immediately shift to structuring liquidity flows across the new organization. The objective is to ensure funding efficiency, mitigate cash drag and trapped cash, and enable flexibility, all within the constraints of the newly formed legal and operational setup.

Key design considerations include:

- Tailored cash pooling and automated cash concentration structures.

- Intercompany funding structures, including currency and transfer pricing alignment and documentation.

- Liquidity buffers tailored to business volatility and seasonality.

- Working capital optimization levers (e.g., payment terms, supplier financing).

Hybrid liquidity management structures, combining centralized oversight with localized autonomy for operational banking, often achieve the best balance. Zanders supports clients based on its wide experience in bank relationship strategy and liquidity optimization for disentanglements.

Optimizing Cash Flow Management towards long-term state

Throughout the transition and towards the steady-state operations, treasury must monitor and manage cash & liquidity against an evolving backdrop of business integration activities and one-off events.

These may include:

- Working capital shifts based on new supply chains or changes in customer behaviour.

- Integration costs linked to systems, people, and process harmonization.

- Divestitures or asset sales to fund operations or sharpen the business focus.

- Cash flow issues caused by system delays or supplier renegotiations.

To address this, Treasury should establish daily cash positioning routines utilizing state-of-the-art technologies and tools, escalation mechanisms, and strong collaboration with FP&A, procurement, and tax. Treasury shall also foster a “Cash First” mindset in the newly created organization. This ensures quick resolution of bottlenecks and reinforce cash flow discipline.

Strategic Liquidity Considerations for Long-Term Success

Cash and liquidity decisions taken during a carve-out will influence the new company’s financial flexibility as it takes quite some time and effort to implement changes in liquidity structures considerably at a later stage. Therefore, treasury should consider as early as possible the following aspects:

- Debt and credit rating impacts, especially if carve-out funding involves leverage.

- Treasury risk centralization (especially FX risk), to reduce cross-border inefficiencies and improve hedging performance.

- Tax and regulatory considerations, such as repatriation limitations, transfer pricing, and cash tax leakage.

- Strategic investment readiness, ensuring adequate liquidity for future M&A, CAPEX, or digital transformation.

The liquidity setup must be scalable, allowing the business to respond confidently to rapid growth, market volatility, or external shocks with resilient measures.

Zanders’ clearly sees a need for treasury functions to evolve into applying strategic enterprise liquidity models providing an efficient framework to link various stakeholders around the office of the CFO, including treasury, FP&A, risk management, accounting and more. A group-wide approach ensures alignment, cooperation and can lead to faster and more informed decision-making processes.

A Roadmap to Liquidity Maturity

The path to liquidity excellence starts with day 1 readiness preparation and implementation but extends far beyond. Treasury should approach this evolution through a structured roadmap that includes:

- Standardization of forecasting processes and technology tools.

- Centralization of liquidity governance, structures, and banking relationships.

- Continuous optimization of working capital, pooling structures, and investment of surplus funds.

- Measurement and benchmarking of liquidity KPIs and stress performance.

We bring a proven methodology and deep experience in day 1 planning and execution, as well as in post-M&A treasury transformation. We help clients design and implement cash and liquidity frameworks that deliver control, flexibility, and strategic value.

In the next edition of this series, we look at implementing effective banking strategy and funding practices within the newly carved-out entity, including key areas of focus and potential challenges.

Citations

- To learn more about this topic, read the whitepaper: Brace for AI-mpact: The six trends driving treasuries forward in 2025 - Zanders ↩︎

Ready to implement cash and liquidity management?

Contact us

Financial crime prevention (FCP) models play a critical role in protecting organizations from money laundering, fraud, and other illicit activities. The effectiveness depends on being able to adapt quickly as criminal tactics evolve.

Yet in many organizations, FCP models still follow the same rigid model validation (MV) process used for credit risk models, a process designed for stability, not agility.

While this ensures consistency, it leaves little room for the frequent updates these models desperately need. With regulators pushing for both effectiveness and compliance, and criminals moving faster than ever, the traditional approach is under pressure. Could generative AI, one of today’s most disruptive technologies, be the key to bridging the gap between strict validation requirements and the need for agility? Could it help us strike a better balance between speed, control, and cost?

The Current State of Model Validation in FCP

Currently, FCP model validation largely follows the framework used for credit risk models, but it faces several critical limitations:

- Manual, time-consuming and resource-intensive: Highly skilled validators must carefully review documentation, code, data pipelines, and monitoring outputs. Currently, it can take two people 6-8 weeks to complete a single validation, leaving them with little capacity to handle additional validations in parallel. In the time it takes to complete a validation, new criminal patterns may already be emerging which require updates or the development of a new model. In addition, delays in feedback between the validation team and developers could further extend the overall timeline.

- Costly: Compliance already consume significant budgets, and under cost-cutting pressures, it becomes increasingly difficult to justify allocating large teams to a single validation.

- Inflexible: Current validation approaches, built around credit risk frameworks, are primarily designed to safeguard capital adequacy. While effective for that purpose, they are not structured to keep up with the fast-moving and evolving patterns of financial crime.

- Capacity constraints: Given the size of most financial crime model portfolios and the frequency of validations required by internal policies, current resources are unlikely to meet long-term expectations. With model inventories expected to grow, this gap will only widen unless capacity is increased.

These challenges highlight a pressing reality: the current validation approach is no longer sustainable. Without significant improvements, organizations risk falling behind with both regulatory expectations and the fast-moving tactics of financial criminals.

Where Can GenAI Make the Biggest Impact in Validation?

In most organizations, models are assessed based on risk, complexity, and probability of failure. This tiered approach helps determine where automation, such as GenAI, can be applied most effectively.:

- High-risk, complex models – Models that are mathematically sophisticated, critical to operations or compliance, and have a higher probability of failure require thorough human validation and expert judgment due to their complexity and potential impact. Therefore, they are not well-suited for GenAI-based validation.

- Low-risk, simpler models – Models that are less mathematically complex, more standardized, and have a lower probability of failure. These are ideal candidates for GenAI, which can handle repetitive validation tasks, review documentation, and generate draft reports.

With GenAI taking care of routine checks on simpler models, human experts can dedicate their time and judgment to the models that truly require deep expertise.

The Role of AI in Financial Crime Model Validation

In practice, how can AI be applied to support model validation? At its core, AI is best suited to take on the repetitive and manual aspects of the process, the tasks that consume valuable time but add little judgment-based value. Instead of replacing experts, AI acts as an efficiency enabler – a “second pair of eyes” that enhances consistency, speeds up routine checks, and leaves human validators free to focus on areas where their expertise is irreplaceable.

Generative AI opens new possibilities for how validation might be approached, with AI driving the validation steps. Instead of starting from scratch, it could make it possible to ingest large volumes of model documentation and generate draft answers to validation questions which are informed by guidance documents, policies, and historical validation reports. It may also be possible to highlight areas that need further clarification, suggesting relevant follow-up questions for discussions between validators and model developers. Where responses are already sufficient, GenAI could enable the automatic closure of open points, keeping the process moving smoothly. Beyond Q&A, it creates the possibility of drafting validation findings based on prior patterns and even producing structured, section-by-section draft validation reports, giving validators a strong foundation to build on, rather than a blank page to start with. Final review and submission are always completed by the validator.

This shift highlights a clear evolution in validation practices. Currently, validation is often characterized by long checklists, manual document reviews, and labor-intensive report writing. With AI support, validation can become faster, more consistent, and highly scalable, allowing humans to focus on important aspects such as judgment, oversight, and final decision-making. With routine and repetitive tasks automated and accelerated through AI, and waiting times between interactions significantly reduced, validators could manage multiple validations in parallel. For model developers, this also means less time spent waiting on feedback, and therefore model developers can drive the speed of validation by submitting evidence faster. In short, AI doesn’t diminish the role of the validator – it elevates it, ensuring their expertise is applied where it delivers the most value. AI will transition the validator from an executor to a supervising role.

How would this Technically Work?

The goal is to create a simple, working version of the idea that shows how GenAI can support validators by automating repetitive steps while keeping humans in full control. It’s not about replacing expertise but about giving validators a smart assistant that can read complex documentation, provide the right information, and draft initial outputs they can refine.

At the center of this setup is an agentic framework built around two main parts: a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system and a prompt creation engine. The RAG system helps the AI pull the most relevant content from internal guidance, policies, and historical validation reports. The prompt engine then turns that information into focused, context-aware prompts, so the AI can generate accurate, useful drafts. Everything runs securely in the organization’s existing cloud environment (for example, in Vertex AI on GCP) to make sure data stays protected and traceable.

The process could look like this:

- The model developer submits documentation, and the AI reviews it to identify relevant guidance and validation standards.

- It drafts initial responses to validation questions, giving the validator something concrete to start from instead of a blank page.

- If information is missing or unclear, the AI compiles structured follow-up questions that the validator can check and send back to the developer.

- When new evidence comes in, the AI reviews it, links it to the open items, and flags what can be closed or what still needs attention.

- Finally, it pulls everything together into a draft validation report with structured sections and proposed findings, ready for the validator to review and finalize.

In this target setup, the AI tool sits between the model developer and the validator. It manages the flow of documents and questions, keeps track of progress, and helps draft findings and reports. Validators remain in charge of every decision but can move through the process much faster and with more consistency. Developers, in turn, get clearer feedback and shorter waiting times.

The outcome is a smoother, more efficient collaboration where AI takes care of the manual groundwork, and humans focus on judgment and oversight, the parts that really matter.

Balancing Benefits and Risks

The potential of AI in model validation is not just theoretical; it comes with tangible benefits. First and foremost is efficiency: automation can significantly reduce the time spent on repetitive validation tasks, freeing experts to focus on higher-value activities. With a basic introduction of AI into the validation process, teams can achieve time savings of around 30%. When introducing a more advanced option, we believe an estimated time saving of up to 80% can be achieved. This naturally translates into cost savings, as the overall validation burden is lowered without compromising quality or increasing headcount. AI also promotes consistency and transparency, applying the same standards uniformly across models. Finally, it offers scalability as organizations can handle a larger portfolio of models without needing to increase headcount, a crucial advantage given current cost-cutting pressure.

As with any innovation, AI in model validation comes with significant risks that must be managed. Generative AI itself carries model risk, including bias, opacity, or “black box” behavior, which could undermine confidence if not carefully controlled. Additional concerns include autonomy risk, where AI might generate outputs without sufficient human guidance, leading to decisions that may be inappropriate or misaligned with validation standards; hallucination risk, where it produces information that seems plausible but is factually incorrect, which could mislead validators if not carefully checked; and incompleteness risk, where AI may overlook parts of a model or validation requirement, resulting in partial or insufficient coverage.

These risks can be managed by humans actively supervising AI and regularly reviewing its outputs. Mistakes are far less likely when experts double-check results, make sure nothing is missing, ensure all information provided is accurate, and stay in control of key decisions. Regulatory acceptance is also a consideration, as supervisors are likely to scrutinize the role of AI and require organizations to explain and justify its use. Finally, careful implementation prevents over-reliance on automation, ensuring human validators remain central to decisions where judgment is essential.

When implemented with care and proper oversight, AI can bring significant benefits to model validation. By combining AI’s capabilities with human judgment, organizations can work more efficiently, handle greater scale, and reduce costs, all while maintaining the trust and rigor that model validation requires.

Our FCP expertise:

Zanders brings a unique combination of expertise in both traditional and AI-driven model validation, helping to navigate the evolving landscape of financial crime model oversight. As a trusted advisor in risk, treasury and finance, Zanders combines deep regulatory knowledge with practical experience, ensuring that solutions are not only innovative but also fully compliant. More importantly, Zanders focuses on pragmatic, regulator-ready designs that bridge cutting-edge technology with compliance requirements. Zanders helps organizations work more efficiently while still meeting the high standards of rigor and trust that regulators expect.

Conclusion

In this FCP series, we have explored bias and fairness, explainability, and model and data drift. Each represents a vital aspect of building models that are not only powerful, but also responsible. Together, they remind us that the real challenge is not just creating models that work, but creating models that we can trust, understand, and sustain over time.

This is what makes AI-enabled model validation a natural next step. As models become more complex, risks evolve faster, and regulatory expectations increase. Organizations need human experts to focus on the areas where their judgment and oversight have the greatest impact, while AI handles the routine tasks.

As we conclude this series, the message is clear:

Organizations that embrace GenAI in their validation processes are not just improving efficiency, but they are shaping the future of model risk management.

AI for financial crime prevention

Get in touch to put GenAI into practice for your model validation process.

Contact us

Does your treasury team feel like you invested in a “Formula 1” TMS but its tires have been flat for a while? Then it is time for a pit stop.

Treasury organizations should periodically review their technology landscape and solutions. The right data foundations, system integrations and top-notch analytics can provide immense business value through better insights, cost savings, workflow automation, and productivity gains.

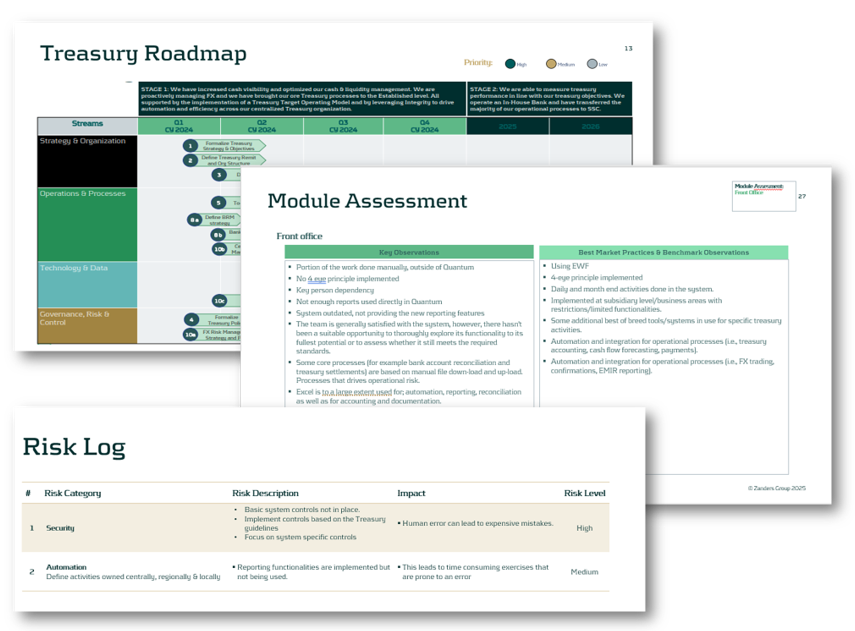

To obtain these benefits, it is necessary to re-assess how your Quantum setup fits your business requirements, evaluate the newest features introduced in quarterly Quantum releases, and define an implementation roadmap after conducting a cost-benefit analysis.

With AI becoming increasingly accessible and more widely integrated into enterprise applications, the opportunities are greater than ever.

Your pit stop with Zanders: Quantum Health Check

At Zanders, our Quantum Health Check is designed to give you a clear, fact-based view of how your treasury system is performing today and where there’s room to grow, considering how your company and treasury organization evolved over the years. Our goal is to ensure that you can drive Quantum like a proper F1 car, benefit from its newest features, and leverage the opportunities related to such technologies as APIs, oData, EWF, dashboards, data warehouses/lakes, BI tools or (Gen)AI.

How do we do it? Each health check is tailored to your specific scope – we listen closely to your priorities and then bring our ideas and suggestions to the table. We dive deep into your Quantum setup and the surrounding solutions – reviewing configuration, data flows, system integrations, reporting, controls, and daily processes – using proven checklists and targeted workshops and interviews.

In less than a month, at the end of the review, we present to you and discuss an easy-to-understand assessment report with a practical action plan and a tailored roadmap, highlighting quick wins and longer-term improvements. Our approach ensures you have the insights needed to stabilize operations, address risks, and unlock new value from Quantum, all while keeping the process smooth and efficient for your treasury team.

TreasuryIQ: AI as Your Pit Crew and Co-Driver

Taking your Quantum Health Check to another level, Zanders seamlessly integrates our proprietary AI platform called TreasuryIQ and our cutting-edge AI services to deliver tangible innovation and value. With an option of involving a dedicated AI engineer throughout the process, clients gain access to hands-on (Gen)AI knowledge, people with experience of implementing AI use cases, and workshops that transform conceptual AI into practical, treasury-specific applications.

Imagine taking your TMS to the next level like swapping out a standard engine for a turbocharged hybrid, engineered for tomorrow’s demands. Our “TreasuryIQ Assistant” acts as your instant expert co-pilot, accelerating user support and insight. Our agentic solutions such as “TreasuryIQ Tester” ensure your workflows are not just automated but intelligently optimized. And specialized solutions such as “Transfer Pricing Suite” show you concrete examples of how AI can fit into your treasury technology picture.

What truly sets Zanders apart is our commitment to co-innovation: after the Health Check, we partner with you to pilot and scale new treasury AI solutions, empowering your team to reimagine what’s possible. With Zanders and TreasuryIQ, your treasury technology isn’t just race-ready – it’s rewriting the rules of the track.

Ready to take the next step?

If any of these questions sound familiar, reach out to us — we’re here to help you get the most from your Quantum investment.

Contact us

As Transfer Pricing compliance becomes increasingly important, discover how treasury can streamline UAE loan pricing with the right tools.

Until recently, most UAE corporate entities were not subject to corporate income tax. This changed with the Ministry of Finance’s announcement on 31 January 2022, introducing a federal corporate tax regime applicable to financial years starting on or after 1 June 2023. The new regime also formalised the UAE’s transfer pricing framework as part of its commitment to the OECD BEPS standards.

Federal Decree-Law No. 47 of 2022 sets out the corporate tax rules and embeds transfer pricing requirements under Articles 34–36 and 55. In addition to the Federal Decree-Law No. 47, the UAE’s Ministry of Finance and Federal Tax Authority also issued additional rules and guidance specific to transfer pricing:

- Ministerial Decision No. 97 of 2023 – Sets out the conditions for the preparation of Master Files and Local Files in line with OECD BEPS Action 13.

- UAE Transfer Pricing Guide – Detailed guidance on the practical impact and implementation of transfer pricing regulations. The guide was prepared in alignment with the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines.

The incorporation of these rules, together with the growing attention from tax authorities on the Transfer Pricing of Intra-Group Loans, has significantly increased the focus of tax and treasury teams on the importance of transfer pricing in the region.

Importance for treasury teams

Over two years on from the UAE’s adoption of a formal corporate income tax regime, the region has positioned itself as a potential financial hub for multinationals to set up their centralised group finance and treasury functions. The UAE’s economic reforms and growing alignment with international financial standards further strengthen its case as a pragmatic and effective financial hub.

Multinationals are increasingly looking towards centralised, in-house financing functions to more effectively navigate variables between markets such as regulatory requirements, currency exposures, and broader liquidity and cash flow targets.

As more multinationals set up financing hubs in the UAE, scrutiny from the Federal Tax Authority will increase accordingly, particularly with a legitimate transfer pricing regime now in place. This means that both treasury teams and tax departments need to price intra-group loans on an arm’s length basis.

Alignment with the OECD TP Guidelines

The UAE follows the OECD TP Guidelines Chapter X for the transfer pricing of intra-group financial transactions, with additional local guidance provided in section 7.1.3.2 of the UAE Transfer Pricing Guide. Intercompany loans must reflect arm’s length terms, including loan amount, maturity, repayment terms, and arm’s length interest rates.

In practice, a 4-step process should be followed to comply with these requirements:

Step 1: As a first step, the terms and conditions should be reviewed to ensure their commercial rationale and that they reflect the actual economic reality of the parties. In this sense, special consideration should be given to the loan amount and whether an independent party would extend such an amount to the borrower. To this end, the so-called Debt Capacity Analyses are performed.

Step 2: As a second step, a credit rating analysis should be performed. While the recommended approach is to follow a bottom-up approach, based on the standalone credit rating of the entity adjusted for group support, in some cases a more simplified top-down credit rating approach can also be considered acceptable.

Step 3: As a third step, the pricing analysis is performed, typically by application of the external CUP method, identifying comparable third-party transactions with similar characteristics. Of course, the necessary comparability adjustments should be performed to reflect the differences between the external comparables and the loan under analysis.

Step 4: Finally, the analysis should be documented in a Transfer Pricing Report, explaining in a transparent manner the analysis performed in the previous steps. It is important to have legal documentation in place, reflecting the terms and conditions of the loan that have been considered during the analysis.

Interest limitation rules:

Alongside traditional transfer pricing regulations, the UAE also enacted interest deductibility rules in Article 30 of the Ministerial Decision No. 120 of 2023. The provisions are broadly modelled after the OECD’s BEPS Action 4. These interest limitation rules should be considered alongside transfer pricing regulations. In principle, net interest expense in the UAE is deductible only up to 30% of the borrower’s adjusted EBITDA. This rule only applies to cumulative interest expense greater than AED 12 million in a given year.

Article 28(1)(b) provides further rules that should apply specifically to intercompany arrangements. In addition to the foundational rule, any intercompany interest expense is non-deductible if:

- The financial arrangement lacks economic substance or commercial purpose; and

- The lender is not subject to a corporate tax rate of more than 9%; and

- The main purpose or one of the main purposes of the loan was to obtain a tax advantage.

Each of these must be proven for any interest deductions to be denied. These rules function to mitigate intergroup profit shifting and hybrid arrangements.

Zanders Transfer Pricing Software as a tool:

As tax authorities intensify their scrutiny, it is essential for companies to carefully adhere to the recommendations outlined above.

Does this mean additional time and resources are required? Not necessarily. Technology provides an opportunity to minimize compliance risks while freeing up valuable time and resources. The Zanders Transfer Pricing Software is an innovative, cloud-based solution designed to automate the transfer pricing compliance of financial transactions.

With over eight years of experience and trusted by more than 90 multinational corporations, our platform is the market-leading solution for intra-group loans, guarantees, and cash pool transactions.

Our clients trust us because we provide:

- Transparent and high-quality embedded intercompany rating models.

- A pricing model based on an automated search for comparable transactions.

- Automatically generated, 40-page OECD-compliant Transfer Pricing reports.

- Debt capacity analyses to support the quantum of debt.

- Legal documentation aligned with the Transfer Pricing analysis.

- Benchmark rates, sovereign spreads, and bond data included in the subscription.

- Expert support from our Transfer Pricing specialists.

- Quick and easy onboarding—completed within a day!

If you are interested in exploring how the Transfer Pricing Software could optimize your transfer pricing processes for financial arrangements, let us know in the contact form below.

Book a demo

Contact us

Zanders partners with Kantox on the latest in hedge accounting software to tackle the challenge of net income variability with full technical support and expert help.

The Challenge

The challenge is well known. Accounting conventions treat derivatives differently from commercial transactions. As a result, even when exposures are perfectly hedged, unrealised FX gains and losses on derivatives can create unwanted swings in net income. The fix is hedge accounting under IFRS and local GAAP—but designing policies, running effectiveness tests, documenting relationships, and producing audit-ready reports can stretch finance teams.

The Solution

Kantox Hedge Accounting Powered by Zanders automates this end to end. The software solution integrates out of the box with Kantox Dynamic Hedging, giving companies a true, end-to-end currency management automation setup that connects risk management and accounting seamlessly.

The benefits are immediate. Companies reduce operational cost and risk versus manual implementation, gain full technical and audit support, and remove net income variability stemming from unrealised FX gains and losses. Finance teams get consistent, audit-ready outputs while freeing resources to focus on higher-value activities.

Zanders & Kantox

Zanders brings deep expertise to the workflow. With more than 400 consultants, 12 offices across 4 continents, and 750+ customers, Zanders is a recognised authority in automated hedge accounting. Teams receive the level of support they need—from day-to-day assistance to premium, customised advisory—to draft hedge accounting policies, address country-specific audit requirements, and keep pace with evolving standards without building costly in-house capabilities.

By combining automation from Kantox with Zanders’ specialist guidance, organizations can implement hedge accounting with confidence—and finally align their FX risk management with their financial reporting.

Learn More

Find out about the full range of features and capabilities and watch the video on the Kantox website.

Interested in Kantox Hedge Accounting? Contact us to learn how to implement it quickly and smoothly.

Contact us

Get in touch to learn more about Kantox Hedge Accounting software and how Zanders can help.

Contact us

The landscape these institutions are operating in is constantly changing. Criminals develop new behaviour, and new methods and technologies become available.

Criminals never stand still, and neither should the models designed to catch them. Across the financial sector, institutions have invested heavily in advanced Financial Crime Prevention (FCP) models to detect fraud and money laundering. Yet the environment these models operate in is evolving faster than ever. As new technologies emerge and criminal behaviors adapt, yesterday’s patterns no longer predict tomorrow’s risks.

Take cryptocurrencies: once niche, now mainstream. Their rise has transformed what “normal” transactions look like, blurring the line between legitimate activity and illicit movement. This shift underscores a growing challenge for banks—model drift. Without continuous monitoring and recalibration, even the most sophisticated FCP models can lose accuracy and allow financial crime to slip through the cracks.

Model Drift, Data Drift, Concept Drift – What Are They?

Model drift is defined as the degradation of the model’s performance over time. This can be due to many factors, such as sampling bias, but also due to data drift or concept drift. Data drift and concept drift are related and occur often at the same time, but tackle a different underlying issue.

Data drift occurs when the distribution of data underlying your model changes. Take for example, bank A which acquires bank B. Such a takeover might change the underlying customer base significantly. Assuming that bank B has a higher risk appetite, these clients likely require different monitoring from the original customer base, e.g. by changing thresholds or developing new rules.

Concept drift on the other hand means that a relationship that a model presupposes deteriorates or does not exist anymore. This can have large effects on the quality of model predictions. For example, criminals continuously develop new money laundering tactics to avoid being detected by ever-improving transaction monitoring models without impacting overall transaction distributions. This way the model still detects the outdated method the criminals used to apply but not the new methods. As a result, the model decreases in effectiveness.

As mentioned above, data drift and concept drift often occur together. An example of these two concepts coming together is for the aforementioned cryptocurrencies. The distribution of cryptocurrencies have shifted significantly with more and larger transactions indicating data drift. In addition cryptocurrencies have gained a lot of popularity amongst criminals for developing new money-laundering schemes indicating concept drift.

How To Monitor Model Drift

Both concept and data drift can occur after the go-live of the model. It is crucial to have proper monitoring in place to timely be alerted. Generally, model monitoring frameworks include periodic review of a models’ effectiveness. Creating awareness for data drift and concept drift during this periodic review can create an alertness if the model performance or underlying distribution significantly shifts. Besides the regular assessment cycle, some monitoring thresholds can be upheld:

- Data drift: measure the underlying distribution of risk drivers at model initiation. Significant distortions in this initial distribution should be bound to some pre-defined limit. Once these thresholds are breached, a review can be initiated to assess its contribution in erroneous predictions. An example of a metric that could be used for this purpose is the Population Stability Index (PSI), which measures the difference between the distributions of two different population samples.

- Concept drift: measure the predictive power of the individual risk drivers against the dependent variable. If there seems to be significant deterioration of the explanatory power, a review of the model design can be initiated. For example by using SHAP-values, the individual contribution of a risk driver towards the general risk classification can be utilized. If these SHAP-values provide a decrease in explanatory power since model initiation, this can indicate concept drift.

Prevent Drift From Derailing Your Models

Besides a solid model monitoring framework and regular periodic reviews of the model, model drift should also be considered during model development. During model (re)development, the following points should be considered to counteract model drift:

- Measure the sensitivity of the model against small changes in averages of your input. Assessment of the impact of changes in individual risk drivers can give insight into over-reliance towards specific characteristics that are prone to change.

- Sensitivity can also be measured towards the change in distribution, such as flattening or skewing the distribution.

- Assess the change to your model when risk drivers are removed. Here, again, the impact should be manageable.

- Investigate the stability of your risk drivers over time.

- Perform a qualitative analysis on the robustness of risk drivers.

These steps give a solid base to include mitigants for data drift and concept drift into your model development cycle.

This article is part of a larger series highlighting crucial topics for the future of financial crime prevention. See an overview of the whole series here.

Creating a solid model development framework that includes model and data drift can be a challenge and requires deep domain experience and experience. If you need guidance in making your models future-proof, Zanders can help.

Want to know how Zanders can support you in this transition? Feel free to reach out through our contact page to get in touch with an expert.

Get FCP support

Talk to an expert to prevent drift from derailing your models and make sure you're set up for the future.

Contact

AI is everywhere – but many treasurers still struggle to move beyond the hype and identify real, value-adding applications. Here is one real way to leverage AI for real value in treasury.

AI is everywhere – but many treasurers still struggle to move beyond the hype and identify real, value-adding applications. That’s why in this blog series, we’ll explore four practical use cases in depth, each resulting in a concrete, actionable application you could begin implementing tomorrow.

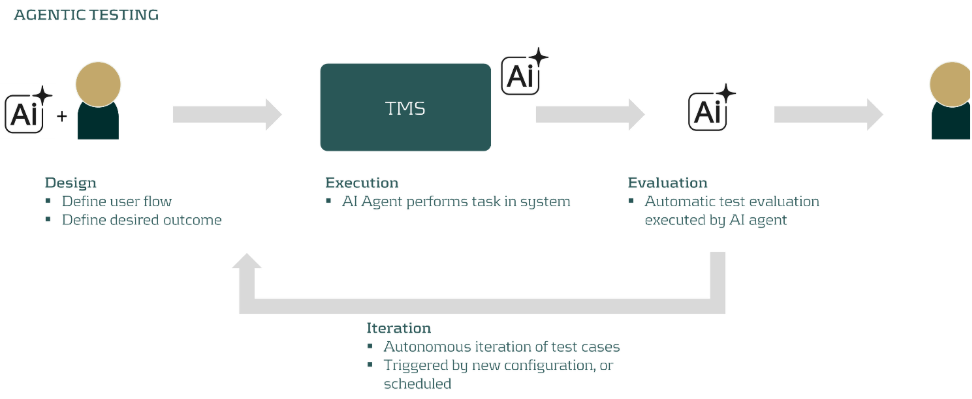

In this blog, we focus on one of the most time-consuming challenges in any treasury transformation: system testing. Testing remains highly manual, repetitive, and resource-intensive. But the rise of AI agents is changing the game, offering a way to make testing faster, more intuitive, and highly repeatable.

The Challenge

Testing is at the heart of every treasury transformation. It’s a meticulous, iterative process: before you even begin, you need a robust set of test cases that reflects your specific workflow to ensure every critical scenario is covered, without drowning in an endless list. Then comes the manual execution, documentation, and feedback cycles, repeated again and again until every issue is resolved.

Even after go-live, the work isn’t over. Regular system updates and configuration changes mean more rounds of regression testing to catch any unexpected side effects. It’s essential work, but it can be a real drain on time and resources.

Now, thanks to AI, there’s a smarter way.

The Solution

AI agents are autonomous actors that can interact directly with your web browser and through that with your Treasury Management System (TMS) to complete tasks and resolve issues. Imagine instructing an AI agent in plain language, and watching it execute complex test cases right in the user interface. The agent is able to navigate to the right page, fill in information in the forms, the buttons, and record output. The flexibility of these agents even allow them to identify error messages and validate the result of a set of actions.

Armed with vendor documentation, solution designs, and implementation blueprints, the AI agent proposes a comprehensive set of test cases and relates those to actions in your system of choice. Users can easily add their own scenarios by simply describing the workflow. The agent then navigates the system, executes the tests, and records the results, all autonomously.

Worried about safety? Don’t be. Today’s test automation tools come with robust guardrails:

- Test environments only: No risk to production.

- Controlled user rights: The agent gets only the permissions it needs.

- Plan mode: The agent presents its action plan for human approval before anything runs.

With these safeguards, the risk of unintended actions is virtually eliminated—while the efficiency gains are game-changing.

You can build AI agents in-house, but many organizations will benefit even more from cloud-based platforms. These solutions:

- Lower deployment costs and speed up implementation

- Offer ready-made integrations

- Enable users to share successful test scenarios

At Zanders, we’ve developed an AI-powered test suite that plugs directly into leading cloud TMS platforms—empowering treasurers to accelerate testing without sacrificing control.

A Real-World Example

Let’s make this tangible. Suppose you want to test a workflow for adjusting FX exposure and generating a report. The AI agent, using system documentation and blueprints, proposes relevant user flows. One test case might be:

“Change the EUR/USD exchange rate to 1.12, create a new EUR/USD FX Forward with a six-month maturity, and run the FX Exposure report.”

The agent executes these steps, records the results, and once the optimal route is captured, can repeat the test autonomously and even evaluate the outputs itself. Over time, you build a powerful, reusable suite of automated test scenarios for both transformation projects and ongoing regression testing.

Conclusion

AI in treasury is no longer a futuristic possibility, it’s a practical, high-impact technology that treasury teams can start leveraging today. Do you want to explore automated testing? Contact us! Are you interested in other concrete use cases, learn more about transforming your treasury operations for the digital age.

Automate your testing

Get in touch to talk to us about automating your treasury testing and how we can help.

Contact us

In collaboration with a leading international bank, Zanders explored how machine learning can support more accurate, scalable, and decision-useful estimates of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity when disclosures fall short.

In the pursuit of climate-aligned finance, financial institutions face a critical challenge: incomplete emissions data. While disclosure frameworks such as the EBA’s Pillar 3 ESG requirements, the ECB’s climate risk guidance, and the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) continue to expand, their scope remains fragmented. Therefore, financial institutions must often assess climate-related financial risks and align portfolios without full visibility into counterparties’ environmental footprints.

In collaboration with a leading international bank, Zanders explored how machine learning can support more accurate, scalable, and decision-useful estimates of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity when disclosures fall short.

The Challenge: Incomplete GHG Emissions Disclosure

Current climate risk assessments rely heavily on firm-disclosed emissions. Yet, many companies, particularly small, private, or non-European, still do not report their GHG emissions. This inconsistency not only limits the accuracy of portfolio-level financed emissions metrics, but also hinders accurate net-zero alignment tracking and regulatory reporting.

To fill this gap, many financial institutions resort to sector-average proxies, such as those recommended by the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF). These proxies assign emissions to non-reporting firms based on average industry and regional emission intensities. While widely adopted, this approach introduces substantial bias, as it overlooks firm-specific drivers such as energy use, capital intensity, or geographic differences. The result is a blind spot: portfolio assessment loses the very granularity needed to distinguish leaders from laggards in the low-carbon transition.

Predicting Emissions Intensity with Machine Learning

The main objective of the study focused on testing various supervised ML models to estimate Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions intensity based on a variety of financial firm-level characteristics. Leveraging an unbalanced panel dataset covering worldwide public and private companies from 2021 to 2025, models were trained to learn from disclosed emissions and predict missing values with greater granularity. The dataset was split into approximately 80 % training and 20 % testing subsets, ensuring that observations from the same company (across different years) did not appear in both sets to prevent information leakage.

Two models were introduced:

- Model 1, a baseline that includes financial and sectoral indicators widely available for banks, such as assets turnover; property, plant and equipment (PPE); earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT); and industry classification.

- Model 2, an extended model that incorporates more advanced and less common variables such as Refinitiv ESG score; energy consumption; and earnings quality rankings.

These predictors were selected based on both academic relevance and practical availability in financial databases such as LSEG Workspace (previous Refinitiv Eikon) and S&P.

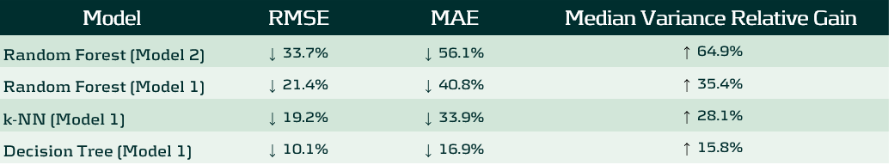

In both Model 1 and Model 2 settings, three algorithms were compared: k-Nearest Neighbours (k-NN), Decision Trees, and Random Forests, chosen for their interpretability and practicality in low-data environments. To assess whether machine learning provides a meaningful improvement over traditional sector-average proxies, both the ML models and PCAF sector-average proxy estimates were examined on a common test set. Unification of this comparison allowed for quantifying the overall predictive gains and evaluating the implications for climate-aligned decision-making in finance.

Models performance was evaluated using standard regression metrics including Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE), ensuring consistency across models and comparison with the baseline. Beyond standard error metrics, performance was also assessed through variance recovery (reported further as Median Variance Relative Gain). This measure captures how effectively each model restores firm-level differentiation in GHG emissions intensity lost under sector-average proxies.

The entire framework was designed to balance predictive accuracy with implementation realism, aiming to improve GHG coverage for financial institutions without relying on black-box techniques or data-heavy infrastructure.

What the Models Revealed

Under each model and method, machine learning substantially outperformed the traditional PCAF proxy approach:

The Random Forest version of Model 2 emerged as the strongest performer, reducing RMSE by roughly one-third, MAE by more than a half and recovering nearly 65% of the intra-sectoral variance lost under sector-average proxies. Model 1, created for banking sector usage, scored a second place under the same Random Forest algorithm, reducing RMSE by 21% and MAE by 41%. This means that the algorithm can effectively differentiate firms within the same industry, being a critical step for a realistic transition-risk modeling or portfolio creation.

Feature importance analysis showed that Energy Use Total, PPE / Total Assets, Asset Turnover and Sector were consistently dominant predictors, confirming that emissions intensity depends jointly on operational efficiency and capital structure. However, the study also tested a transfer learning approach, where models trained only on high-disclosure sectors with sufficient reporting coverage were applied to low-disclosure sectors, unseen during training. The results showed a substantial decline in accuracy, suggesting that emission patterns are highly sector specific. In practice, this means that for ML models to exceed sector-average proxies in the GHG emission estimation context, models should be trained on datasets that include all sectors, rather than relying on samples limited to a few well-disclosing industries.

Why This Matters

More accurate emissions estimation directly supports key pillars of sustainable finance. It enhances portfolio alignment assessments, scenario analysis, and climate risk disclosure under frameworks such as Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). Moreover, improved firm-level granularity enables financial institutions to better understand which clients are leading or lagging in the transition to a low-carbon economy.

By replacing rigid proxies with data-driven predictions, financial institutions can move one step closer to climate data maturity, where decisions are no longer held back by disclosure gaps but empowered by intelligent estimation.

What Zanders Can Do

As regulatory expectations tighten and data coverage remains incomplete, financial institutions need solutions that are both technically rigorous and operationally feasible. Whether addressing climate-related credit exposures, integrating ESG into portfolio construction, or navigating disclosure obligations, institutions must adopt frameworks that are adaptive, data-driven, and aligned with supervisory standards.

By combining quantitative modeling expertise, climate risk analytics, and regulatory knowledge, Zanders helps institutions move beyond generic estimates and static proxies.

Want to find out more about how we can support you in building practical ESG risk management solutions? Our ESG experts will be happy to assist you. Visit the Zanders ESG page to know more.

Get ESG support

Talk to an expert about your ESG risk management strategy and see how we can help.

Contact

In banks’ boardrooms and compliance departments, a quiet but persistent concern echoes: “Can we trust AI in high-stakes decision-making?”

For many companies, especially in regulated industries like finance, the fear of AI is not just philosophical; it’s a practical challenge. It stems from a perceived loss of control, a lack of transparency, and the worry that decisions made by complex models might be difficult to justify to regulators, auditors, or the public.

This fear is understandable. When machine learning models autonomously flag transactions, deny loans, or possibly even escalate alerts to authorities, the stakes are high. The consequences affect not just business outcomes, but reputations, regulatory standing, and real people’s lives. In Financial Crime Prevention (FCP), where analysts must decide whether to file a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR), the need for clarity is of great importance.

This fear doesn’t have to mean that these models have no place in these departments. Rather, it can guide us to the correct place. The focus should shift from: "how the model works" to: "how the model helps."

Empowering Analysts

In AI deployments, explainability is treated as a technical afterthought, a set of metrics or plots that satisfy internal documentation or regulatory checklists. But in FCP, the true end-user of an AI system is the analyst. They are the ones who must interpret alerts, justify decisions, and ensure compliance. Their job is not to understand gradient boosting or SHAP values, analysts should have a focus to make the results defensible and take informed decisions under pressure.

Human-centered explainability means designing explanations that support this task. It’s not about simplifying for the sake of clarity, it’s about making the explanation meaningful and relevant to the task at hand. This approach should turn the model from a black box into a collaborative partner.

Instead of presenting abstract SHAP plots, one could consider:

- Top contributing risk factors for each alert, along with an explanation of what each factor represents. While most models already use feature importance to describe their behavior, analysts tend to interpret these factors from a risk perspective. A simple way would be providing a mapping between model features and risk indicators which could help analysts better understand what drives an alert and why it matters.

- Narrative summaries that explain why a transaction deviates from expected behavior. One could for instance leverage the power of LLM’s for transforming data into plain-language interpretations.

- Consistency checks that show how similar cases were treated, building trust in the system’s fairness.

Too often, explainability efforts focus on stakeholders around the model; data scientists, compliance officers, or regulators. But the real test of explainability lies with the analyst who must act on the model’s output. By centering design on their needs, we shift the conversation from how the model works to how the model helps.

This shift doesn’t just improve usability; it builds trust. And in a domain like FCP, trust is everything.

Explainability as a Bridge, not a Barrier

AI continues to be a sensitive topic in the risk-conscious world of Financial Crime Prevention, largely because its explainability focuses heavily on technical model details. But the real value of AI lies in how it supports analysts, helping them interpret alerts, make informed decisions, and justify their actions with confidence. That’s why explainability should be designed with the analyst in mind. By doing this, AI becomes not only more transparent, but also more useful, more responsible, and more trusted.

Understanding and applying explainability metrics in Financial Crime Prevention (FCP) is no longer just a technical exercise, but a human-centered challenge.

As highlighted in our blog series on the future of FCP, explainability is just one of the critical pillars shaping responsible AI adoption in this domain. If you're navigating the complexities of explainability and wanting to ensure your AI systems are not only compliant but also trusted and usable by those on the front lines, Zanders can help.

Get AI support

Talk to an expert about ensuring AI compliance and usability in financial crime prevention.

Contact

In recent years, bias and fairness in AI models have become critical topics of discussion, especially as algorithmic decision-making has led to unintended and sometimes harmful consequences for specific groups.

In recent years, bias1 and fairness in AI models have become critical topics of discussion, especially as algorithmic decision-making has led to unintended and sometimes harmful consequences for specific groups. Notable examples include the “Toeslagenaffaire “ in The Netherlands (Toeslagenaffaire) and the COMPAS case in the United States (COMPAS case). Both of these examples highlight how models that include algorithmic decision making can display unwanted bias without proper governance.

In the Financial Crime Prevention (FCP) domain, AI models are often used to detect criminal behaviour such as fraudulent transactions, money laundering, and tax evasion. These models are not just operational tools – they are subject to regulation. For instance, National Central Banks may mandate that banks demonstrate sufficient effort in identifying financial crime (The DNB on Money Laundering and combating criminal money), with penalties for underperformance. Performance is typically measured using (a derivative of) recall2, which measures the model’s ability to identify as many true cases of criminal behaviour as possible.

Recently, several Dutch banks faced fines from regulators for failing to meet these requirements, underscoring the pressure to maximize recall.

However, this focus on maximizing recall must be balanced with fairness. Regulators also require banks to detect and mitigate unwanted bias in their models (EBA report, AI Act), which relates to the metric precision2 – the proportion of flagged cases that are actually criminal. A low precision rate can result in clients being wrongly flagged, which raises ethical and legal concerns.

The Pitfalls of Conventional Bias Fixes

Assessing the fairness of a model typically includes comparing precision-like metrics across different groups with similar sensitive information (e.g., groups based on gender or ethnicity). If significant disparities are observed between groups, steps are typically taken to align the precision values more closely. While this approach is popular and intuitive, it comes with several challenges:

- Conflicting objectives: Precision and recall are inherently at odds. Optimizing for one generally compromises the other. Banks must navigate regulatory demands for high recall while also ensuring fair treatment across groups, with no established best practices to guide these trade-offs.

- Levelling down: Achieving equal precision across groups can involve either improving the disadvantaged group's performance or reducing the advantaged group's performance. In practice, improving precision for disadvantaged groups is often infeasible due to limited data or inconsistent behavioural patterns. This leads to "levelling down" – artificially lowering the precision of the advantaged group to achieve parity (The Unfairness of Fair Machine Learning: Levelling down and strict egalitarianism by default). While this may equalize precision metrics, it does not improve outcomes for the disadvantaged group and often degrades overall model performance. Therefore, whether this approach is truly fair remains a subject of debate.

In the context of FCP, one could challenge the assumption that the goal should be to achieve strict statistical parity between groups at the cost of lower recall. For a model that e.g. detects fraudulent transactions, achieving strict parity by decreasing the recall for advantaged groups could be considered inappropriate, with potentially harmful societal consequences. Levelling down is a classic example of Goodhart’s Law that “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”. - Use of sensitive information: Testing for unwanted model bias usually involves customer segmentation based on sensitive attributes. However, this process can lead to the sensitive data being used in the model development process, either directly (e.g., as input features) or indirectly (e.g., through group-specific decision rules or parameters). Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), this is generally prohibited.

Potential Next Steps

Bias and fairness considerations, especially within Financial Crime Prevention, require moving beyond the simple pursuit of strict statistical parity. In addition to established practices, more nuanced and responsible approaches should be considered:

- Establish a bank-wide “bias and fairness” committee: Create a bank-wide diverse committee consisting of experts across different departments such as modeling & data, compliance, and risk. This committee should define unified fairness principles, oversee their consistent application across departments, and act as a governance hub for addressing emerging fairness concerns in AI-driven decision-making.

- Develop an impact-based fairness framework: Move beyond solely equalizing metrics by building a framework that measures the tangible impact of bias on different customer groups. This enables institutions to focus resources where potential harm is greatest, ensuring fairness interventions deliver meaningful outcomes.

- Leverage explainability tools to detect hidden biases: Tools like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) are commonly used to meet regulatory requirements regarding explainability. Beyond compliance, SHAP can also help uncover which (combinations of) features act as proxies for sensitive attributes like gender or ethnicity. This could help to proactively detect hidden biases and strengthen fairness in FCP models.

This article is part of a larger series highlighting crucial topics for the future of financial crime prevention. See an overview of the whole series here.

Navigating the complex ecosystem of bias and fairness metrics in the context of FCP demands deep domain expertise and a clear understanding of the regulatory and ethical landscape. If you need guidance in translating complex fairness metrics into actionable, compliant, and effective practices, Zanders can help.

Citations

- Note that in this blog, bias refers to ethical bias. Specifically, cases where a model produces systematically more favorable or unfavorable outcomes for certain groups of individuals based on sensitive attributes such as ethnicity, gender, or similar characteristics. ↩︎

- In the bias and fairness literature, there is a large amount of metrics used, typically categorized in Independence, Sufficiency and Separation metrics (see e.g. A clarification of the nuances in the fairness metrics landscape | Scientific Reports ). For the purpose of this blog, the metrics Precision and Recall are used, as these are most commonly used within the context of FCP. ↩︎