ESG-related derivatives: regulation & valuation

ESG-related derivatives: regulation & valuation

The most popular financial instruments in this regard are sustainability-linked loans and bonds. But more recently, corporates also started to focus on ESG-related derivatives. In short, these derivatives provide corporates with a financial incentive to improve their ESG performance, for instance by linking it to a sustainable KPI. This article aims to provide some guidance on the impact of regulation around ESG-related derivatives.

As covered in our first ESG-related derivatives article, a broad spectrum of instruments is included in this asset class, the most innovative ones being emission trading derivatives, renewable energy and fuel derivatives, and sustainability-linked derivatives (SLDs).

Currently, market participants and regulatory bodies are assessing if, and how new types of derivatives fit into existing derivatives regulation. In this regard, European and UK regulators are at the forefront of the regulatory review to foster activity and ensure safety of financial markets. Since it’s especially challenging for market participants to comprehend the impact of these regulations and the valuation implications of SLDs, we aim to provide guidance to corporates on these matters, with a special focus on the implications for corporate treasury.

Categorization & classification

When issuing an SLD, it’s important to understand which category the respective SLD falls in. That is, whether the SLD incorporates KPIs and the impact of cashflows in the derivatives instrument (category 1), or if the KPIs and related cashflows are stated in a separate agreement, in which the underlying derivatives transaction is mentioned for setting the reference amount to compute the KPI-linked cashflow (category 2). This categorization makes it easier to understand the regulations applying to the SLD, and the implications of those regulations.

In general, a category 1 SLD will be classified as derivative under European and UK regulations, and swap under US regulations, if the underlying financial contract is already classified as such. The addition of KPI elements to the underlying financial instrument is unlikely to change that classification.

Whether a category 2 SLD is classified as a derivative or swap is somewhat more complicated. In Europe, this type of SLD is classified as a derivative if it falls within the MIFID II catch-all provision, which must be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Overall, instruments that are classified as derivatives in Europe will also be classified as such in the UK. But to elaborate, a category 2 SLD will classified as a derivative in the UK if the payments of the financial instrument vary based on fluctuations in the KPIs.

When a category 2 SLD is issued in the US, it will only be classified as a swap if KPI-linked payments within the financial agreement go in two directions. Even if that is the case, the SLD may still be eligible for the status as commercial agreement outside of swaps regulation, but that is specific to facts and circumstances.

Apart from the classification as derivative or swap, it is also helpful to determine whether an SLD could be considered a hedging contract, so that it is eligible for hedging exemptions. The requirements for this are similar in Europe, the UK, and the US. Generally, category 1 SLDs are considered hedging contracts if the underlying instruments still follow the purpose of hedging commercial risks, after the KPI is incorporated. Category 2 SLDs are normally issued to meet sustainability goals, instead of hedging purposes. Therefore, it is unlikely that this category of SLDs will be classified as hedging contracts.

Regulation & valuation implications

When issuing an SLD that is classified as a derivative or swap, there are several regulatory and valuation implications relevant to treasury. These implications can be split up in six types which we will now explain in more detail. The six types (risk management, reporting, disclosure, benchmark-related considerations, prudential requirements, and valuation) are similar for corporates across Europe, the UK, and the US, unless otherwise mentioned.

Risk management

As is the case for other derivatives and swaps, corporate treasuries must meet confirmation requirements, undertake portfolio reconciliation, and perform portfolio compression for SLDs. Additionally, regulated companies are required to construct effective risk procedures for risk management, which includes documenting all risks associated with KPI-linked cashflows. While these points might be business as usual, it must also be determined if and how KPI-linked cashflows should be modeled for valuation obligations that apply to derivatives and swaps. For instance, initial margin models might need to be adjusted for SLDs, so they capture KPI-linked risks accurately.

Reporting

Corporate treasuries must report SLDs to trade repositories in Europe and the UK, and to swap data repositories in the US. Since these repositories require companies to report in line with prescriptive frameworks that do not specifically cover SLDs, it should be considered how to report KPI-linked features. As this is currently not clearly defined, issuers of SLDs are advised to discuss the establishment of clear reporting guidelines for this financial instrument with regulators and repositories. A good starting point for this could be the mark-to-market or mark-to-model valuation part of the EMIR reporting regulations.

Disclosure

Only Treasuries of European financial entities will be involved in meeting disclosure requirements of SLDs, as the legislation in the UK and US is behind on Europe in this respect, and non-financial market participants are not as strictly regulated. From January 2023, the second phase of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) will be in place, which requires financial companies to report periodically, and provide pre-contractual disclosures on SLDs. Treasuries of investment firms and portfolio managers are ought to contribute to this by reporting on sustainability-related impact of the SLDs compared to the impact of reference index and broad market index with sustainability indicators. In addition, they could leverage their knowledge of financial instruments to evaluate the probable impacts of sustainability risks on the returns of the SLDs.

Benchmark-related implications

In case the KPI of an SLD references or includes an index, it could be defined as a benchmark under European and UK legislation. In such cases, treasuries are advised to follow the same policy they have in place for benchmarks incorporated in other brown derivatives. Specific benchmark regulations in the US are currently non-existent, however, many US benchmark administrators maintain policies in compliance with the same principles as where the European and UK benchmark legislation is built on.

Prudential requirements

Since treasury departments of corporates around the world are required to calculate risk-weighted exposures for derivatives transactions as well as non-derivatives transactions, this is not different for SLDs. While there is currently little guidance on this for SLDs explicitly, that may change in the near future, as US prudential regulators are assessing the nature of the risk that is being assumed with in-scope market participants.

Valuation

The SLD market is still in its infancy, with SLD contracts being drawn up are often specific to the company issuing it, and therefore tailor made. The trading volume must go up, trade datasets are to be accurately maintained, and documentation should be standardized on a global scale for the market to reach transparency and efficiency. This will lead to the possibility of accurate pricing and reliable cashflow management of this financial instrument and increases the ability to hedge the ESG component.

To conclude

As aforementioned, the ESG-related derivatives market and the SLD market within it are still in the development phase. Therefore, regulations and their implications will evolve swiftly. However, the key points to consider for corporate treasury when issuing an SLD presented in this article can prove to be a good starting point for meeting regulatory requirements as well as developing accurate valuation methodology. This is important, since these derivatives transactions will be crucial for facilitating the lending, investment and debt issuance required to meet the ESG ambitions of Europe, the UK, and the US.

For more information on ESG issues, please contact Joris van den Beld or Sander van Tol.

Impact of EU Sustainable Finance Action Plan on Risk Management – Round-table Summary

ESG-related derivatives: regulation & valuation

This topic is gaining momentum because of the European Commission’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan and associated regulatory changes.

One of the new requirements is that asset managers must incorporate sustainability risks in their risk management and reporting as of August 2022. This means that these risks must be measured, assessed and mitigated. However, this is not an easy task due to a lack of uniformity in risk management approaches and lagging data quality.

This prompted AF Advisors and Zanders to organize a round-table session on the subject. The large session turnout showed the importance of managing sustainability risks for the asset management sector. Parties that manage a total of no less than EUR 2.5 trillion in assets joined the session, including a broad selection of the largest asset managers active in the Netherlands. This attendance led to good, in-depth discussions. The discussion was preceded and inspired by a presentation from one of the expertized asset managers in the field of sustainability on how they mitigate, assess and monitor sustainability risks. Two hours of lively discussion is difficult to summarize but we would like to share a few interesting takeaways. Note that these takeaways do not necessarily represent the views of all the participants, though are merely an overview of the topics that were discussed.

Key takeaways

Financial risk management departments increasingly in the lead

While a few years ago, sustainability risks and the management of these risks were still the task of responsible investing teams in many organizations, this task is increasingly being taken up by financial risk managing departments as these are increasingly capable to quantify sustainability risks. This shift leads to new techniques and new requirements for data. Where previously exclusions were an important method for many parties, an integrated portfolio approach is emerging.

Lack of uniformity in the assessment of sustainability risks

The two main problems in managing sustainability risks are a lack of uniformity in approaches and a limited data quality or availability. Limited data quality is a well-known topic, especially for alternative asset classes. Specialized data vendors will be required to address these issues.

Important to realize, however, is that sustainability risk is such a broad and young concept that it is open to many interpretations. This means that the way in which sustainability risks are assessed can still differ considerably between parties. The benefit is that the different approaches help to speed up the evolvement of this new area. In the longer term it is expected that the assessments converge to a best market practice. Until then, there will be little standardization and different use of terminology. This is especially problematic in a multi-client environment with varying clients’ needs. Enforced communication by the regulator can therefore lead to outcomes that are hard to compare and interpret for clients. Listing definitions used and an explanation of the methodologies used is vital in communication on sustainability risks to clients.

ESG risk ratings are most popular concept despite drawbacks

The most frequently mentioned way in which sustainability risks are monitored is by means of environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk ratings. For example, by comparing a portfolio’s ESG scores with the scores of a corresponding benchmark and by limiting deviations. By using these ratings, environmental, social and governance factors are included. The major drawback of this approach is that it is partly backward-looking. Participants agreed, due to the long horizon over which most risks materialize, traditional (backward-looking) risk models may not be the most suited.

Most forward-looking data is available for climate risks. In addition to the use of ESG scores, a climate risk methodology is therefore desirable.

Not only European legislation matters

Next to European regulation, it is also important to consider emerging global initiatives and other regulation and reporting frameworks. US regulations such as US SDR can impact organizations and the approaches to sustainability risks to some extent. Global initiatives such as TCFD and TNFD are likely to influence and affect organizations’ risk management processes as well. Potential overlap must be analyzed so that an asset managers can face the challenges efficiently.

Internal organization

Sustainability risks can be defined and monitored at various levels of an organization. Portfolio managers should take them into account in the selection of investments. Second line monitoring and independent assessments must be in place. It is important to realize that this is not a topic that only affects the investment and risk management teams. The legislation explicitly places responsibility for managing sustainability risks on the board level and requires internal reporting, controls and sufficient internal knowledge of the topic.

Conclusion

Sustainability risk management is an important topic that asset managers will need to be working on in the coming years. It is expected that this field will evolve over time, it was even referred to as a ‘journey’. The deadline of MiFID, AIFMD and UCITS in August 2022 – date on which amendments of these regulations to incorporate sustainability risks come into effect – is an important first regulatory milestone but will certainly not be the last. With the organization of the round table, we hope to have assisted parties in getting a better understanding of the topic and to have contributed to their journey.

The ESG data challenge

ESG-related derivatives: regulation & valuation

But to seize the opportunities ESG must become an integrated part of a bank’s strategy, risk management and disclosure regimes. High-quality data is instrumental to identify and measure ESG risks, but it can be lacking. FIs need to improve their internal data and use of external private and public vendors like Moody’s or the IMF, while developing a framework that plugs any data gaps.

The lack of appropriate ESG data is considered one of the main challenges for many FIs, but proxies, such as using a building’s energy rating to work out its carbon emissions, can be used.

FIs need climate change-related data that isn’t always available if you don’t know where to look. This article will give you an overview of the most relevant data vendors and provide suggestions on how to treat missing data gaps in order to get a comprehensive ESG framework for the green future where carbon measurement, assessment, reporting and trading will be vital

The data challenge

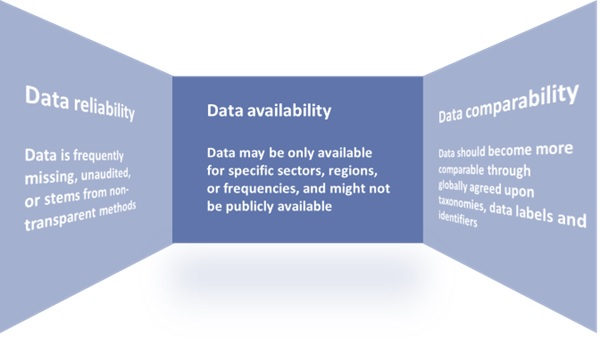

In May 2021, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) published a ‘Progress report on bridging data gaps’. In this report, the NGFS writes that meeting climate-related data needs is a challenge that can be described along the following three dimensions:

- data availability,

- reliability,

- & comparability.

A further breakdown of the challenges related to these dimensions can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The dimensions of the climate-related data challenge.

Source: Graphic adapted by Zanders from a NGFS report entitled: ‘Progress report on bridging data gaps’ (2021).

Key financial metrics

The NGFS writes that a mix of policy interventions is necessary to ensure climate-related data is based on three building blocks:

- Common and consistent global disclosure standards.

- A minimally accepted global taxonomy.

- Consistent metrics, labels, and methodological standards.

EU Taxonomy, CSRD & EBA’s 3 ESG risk disclosure standards

Several initiatives have started to ignite these needed policy interventions. For example, the EU Taxonomy, introduced by the European Commission (EC), is a classification system for environmentally sustainable activities. In addition, the recently approved Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) provides ESG reporting rules for large listed and non-listed companies in the EU, including several FIs. The aim of the CSRD is to prevent greenwashing and to provide the basis for global sustainability reporting standards. Another example of a disclosure standard is the binding standards on Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks developed by the European Banking Authority (EBA).

Even though policy, law and regulation makers have a big part to play in the data challenge, there are also steps that individual institutions could and should take to improve their own ESG data gaps. Regulatory bodies such as the EBA and the European Central Bank (ECB) have shared their expectations and recommendations on the management of ESG data with FIs.

To illustrate, the EBA recommends FIs “[identify] the gaps they are facing in terms of data and methodologies and take remedial action” and the ECB expects institutions to “assess their data needs in order to inform their strategy-setting and risk management, to identify the gaps compared with current data and to devise a plan to overcome these gaps and tackle any insufficiencies”

Collecting data

Collecting ESG data is a challenging exercise. A distinction can be made between collecting data for large market cap companies, and small cap companies and retail clients. Although large cap companies tend to be more transparent, the data often is dispersed over multiple reports – for example, corporate sustainability reports, annual reports, emissions disclosures, company websites, and so on.

For small cap companies and retail clients, the data is more difficult to acquire. Data that is not publicly available could be gathered bilaterally from clients. For example, one European bank has developed an annual client questionnaire to collect data from its clients.

Gathering data from various reports or bilaterally from clients might not always be the best option, however, because it is time consuming or because the data is not available, reliable, or comparable. Two alternatives are:

- Use tools to collect the data. For example, using open-source tooling from the Two Degrees Investing Initiative (2DII) to calculate Paris Agreement Capital Transition Assessment (PACTA) portfolio alignment.

- Collect data from other external data sources, such as S&P Global.

This could be forward-looking external data on macro-economic expectations, international climate scenarios, financial market data or sectoral climate developments. Below we discuss some sources for external ESG and climate change-related data.

External data

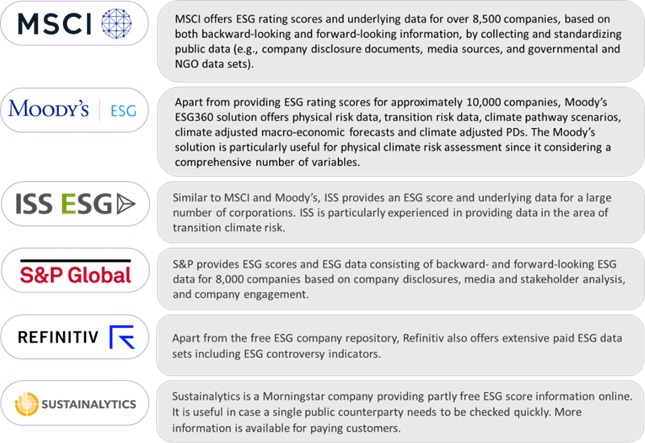

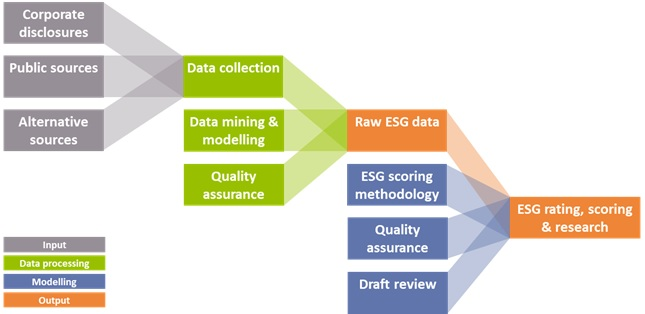

Some of Zanders’ clients resort to vendor solutions for acquiring their ESG data. The most commonly observed solutions, in random order, are:

All the solutions above provide an aid to determine if climate related performance data is lacking, or can assist in reporting comparable and reliable data. They all apply a similar process of collecting the data and determining ESG scores, which is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Data collection process for ESG data solutions (Source: Zanders).

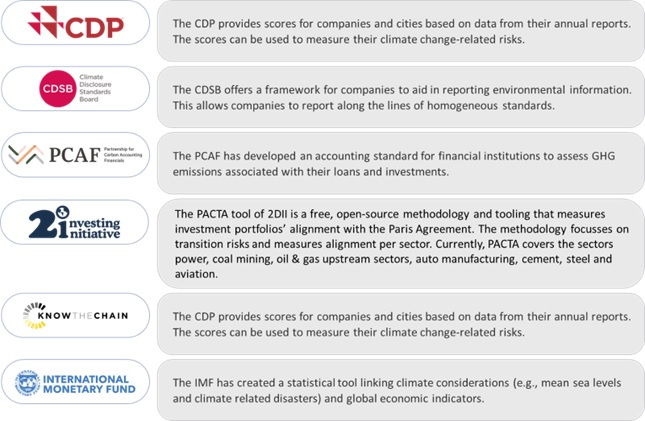

Additionally, public and non-commercial data and solution providers are available, such as:

Missing data

Given the data challenges, it is nearly impossible to create a complete data set. Until that is possible, there are several (temporary) methods to deal with missing data:

- Find a comparable loan, asset, or company for which the required data is available.

- Distribute sector data based on market share of individual companies. For example, assign 10% of the estimated emission of sector X to company Y based on its market share of 10%.

- Find a proxy, comparable or second-best metric. For example, by taking the energy label as a proxy for CO2 emission related to properties, or by excluding scope 3 emissions and focusing on scope 1 and 2 emissions.

- Change the granularity level. For example, by gathering data on sector level rather than on individual positions.

- Fill in the gaps with statistical or machine learning techniques.

Conclusion

The increased attention to integrating ESG risks into existing risk frameworks has led to a need for FIs to collect and disclose meaningful data on ESG factors. However, there is still a lack of data availability, reliability, and comparability.

Several regulatory and political efforts are ongoing to tackle this data challenge, such as the EU taxonomy. More policy interventions, however, are required. Examples are additional mandatory disclosure requirements, an audit and validation framework for ESG data, and social and governance taxonomies that classify economic activities that contribute to social and governance goals.

In the meantime, FIs have to find ways to produce meaningful insights and comply with regulatory requirements related to ESG risks. Zanders has experienced that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for defining, selecting, implementing, and disclosing relevant data and metrics. It is dependent on the composition of the asset and loan portfolio, the use of the data, and the data that is (already) available. Regardless of how the lack of data is solved, it is important that FIs are transparent about their choices and methodologies, and that the related metrics and scorings are explainable and intuitive.

Sources:

https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/progress_report_on_bridging_data_gaps.pdf

https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/banking-and-finance/sustainable-finance/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220620IPR33413/new-social-and-environmental-reporting-rules-for-large-companies

https://zandersgroup.com/en/insights/blog/ebas-binding-standards-on-pillar-3-disclosures-on-esg-risks

https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/documents/files/document_library/Publications/Reports/2021/1015656/EBA%20Report%20on%20ESG%20risks%20management%20and%20supervision.pdf

https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.202011finalguideonclimate-relatedandenvironmentalrisks~58213f6564.en.pdf

https://2degrees-investing.org/resource/pacta/

The ECB published the results of its climate risk stress test

ESG-related derivatives: regulation & valuation

In total 104 banks participated in the stress test that was intended as a learning exercise, for the ECB and the participating banks alike. In this article we provide a brief overview of the main results.

The ECB’s goal with the climate risk stress test was to assess the progress banks have made in developing climate risk stress-testing frameworks and the corresponding projections, as well as understanding the exposures of banks with respect to both transition and physical climate change risks. The stress test therefore consisted of three modules: 1) a qualitative questionnaire to assess the bank’s climate risk stress testing capabilities, 2) two climate risk metrics showing the sensitivity of the banks’ income to transition risk and their exposure to carbon emission-intensive industries, and 3) constrained bottom-up stress test projections for four scenarios specified by the ECB1. The third module only had to be completed by 41 directly supervised banks to limit the burden for some of the smaller banks included in the climate risk stress test.

An understatement of the true risk

The constrained bottom-up stress test projections show that the combined market and credit risk losses for the 41 banks in the sample amount to approximately EUR 70 billion in the short-term disorderly transition scenario. The ECB emphasizes that this probably is an understatement of the true risk, because it does not consider the scenarios underlying the stress test to be ‘adverse’. Second round economic effects from climate risk changes have, for example, not been factored in. Furthermore, only a third of the total exposures of the 41 banks were in scope and, on top of that, the ECB considers the banks’ modeling capabilities to be ‘rudimentary’ in this stage: they report that around 60% of the banks do not yet have a well-integrated climate risk stress testing framework in place, and they expect that it will take several years before banks achieve this. Even though banks are not meeting the ECB’s expectations yet, the ECB does conclude that banks have made considerable progress with respect to their climate stress testing capabilities.

Be aware of clients’ transition plans

A further analysis of the results shows that the share of interest income related to the 22 most carbon-intensive industries amounts to more than 60% of the total non-financial corporate interest income (on average for the banks in the sample). Interestingly, this is higher than the share of these sectors (around 54%) in the EU economy in terms of gross added value. The ECB argues that banks should be very much aware of the transition plans of their clients to manage potential future transition risks in their portfolio. The exposure to physical risks is much more varied across the sample of banks. It primarily depends on the geographical location of their lending portfolios’ assets.

The ECB points out that only a few banks account for climate risk in their credit risk models. In many cases, the credit risk parameters are fairly insensitive to the climate change scenarios used in the stress test. They also report that only one in five banks factor climate risk into their loan origination processes. A final point of attention is data availability. In many cases, proxies instead of actual counterparty data have been used to measure (for example) greenhouse gas emissions, especially for Scope 3. Consequently, the ECB is also promoting a higher level of customer engagement to improve in this area.

Many deficiencies, data gaps and inconsistencies

The outcome of the climate risk stress test will not have direct implications for a bank’s capital requirements, but it will be considered from a qualitative point of view as part of the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). This will be complemented by the results from the ongoing thematic review that is focused on the way banks consider climate-related and environmental risks into their risk management frameworks. The combination will indicate to the ECB how well a bank is meeting the expectations laid down in the ‘Guide on climate-related and environmental risks’ that was published by the ECB in November 2020.

The ECB notes that the exercise revealed many deficiencies, data gaps and inconsistencies across institutions and expects banks to make substantial further progress in the coming years. Furthermore, the ECB concludes that banks need to increase customer engagement to obtain relevant company-level information on greenhouse gas emissions, as well as to invest further in the methodological assumptions that are used to arrive at proxies.

If you are looking for support with the integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance risk factors into your existing risk frameworks, please reach out to us.

Notes

1) See our earlier article on the ECB’s climate stress test methodology for more details.

Integrating ESG risks into a bank’s credit risk framework

On Thursday 9 June, we hosted a roundtable in our head office in Utrecht titled ’Integrating ESG risks into a bank’s credit risk framework’. The roundtable was attended by credit and climate risk managers, as well as model validators, working for Dutch banks of different sizes. In this article we briefly describe Zanders’ view on this topic and share the key insights of the roundtable.

The last three to four years have seen a rapid increase in the number of publications and guidance from regulators and industry bodies. Environmental risk is currently receiving the most attention, triggered by the alarming reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). These reports show that it is a formidable, global challenge to shift to a sustainable economy in order to reduce environmental impact.

Zanders’ view

Zanders believes that banks have an important role to play in this transition. Banks can provide financing to corporates and households to help them mitigate or adapt to climate change, and they can support the development of new products such as sustainability-linked derivatives. At the same time, banks need to integrate ESG risk factors into their existing risk processes to prepare for the new risks that may arise in the future. Banks and regulators so far have mostly focused on credit risk.

We believe that the nature and materiality of ESG risks for the bank and its counterparties should be fully understood, before making appropriate adjustments to risk models such as rating, pricing, and capital models. This assessment allows ESG risks to be appropriately integrated into the credit risk framework. To perform this assessment, banks may consider the following four steps:

- Step 1: Identification. A bank can identify the possible transmission channels via which ESG risk factors can impact the credit risk profile of the bank. This can be through direct exposures, or indirectly via the credit risk profile of the bank’s counterparties. This can for example be done on portfolio or sector level.

- Step 2: Materiality. The materiality of the identified ESG risk factors can be assessed by assigning them scores on impact and likelihood. This process can be supported by identifying (quantitative) internal and external sources from the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), governmental bodies, or ESG data providers.

- Step 3: Metrics. For the material ESG risk factors, relevant and feasible metrics may be identified. By setting limits in line with the Risk Appetite Statement (RAS) of the bank, or in line with external benchmarks (e.g., a climate science-based emission path that follows the Paris Agreement), the exposure can be managed.

- Step 4: Verification. Because of the many qualitative aspects of the aforementioned steps, it is important to verify the outcomes of the assessment with portfolio and credit risk experts.

Key insights

Prior to the roundtable, Zanders performed a survey to understand the progress that Dutch banks are marking with the integration of ESG risks into their credit risk framework, and the challenges they are facing.

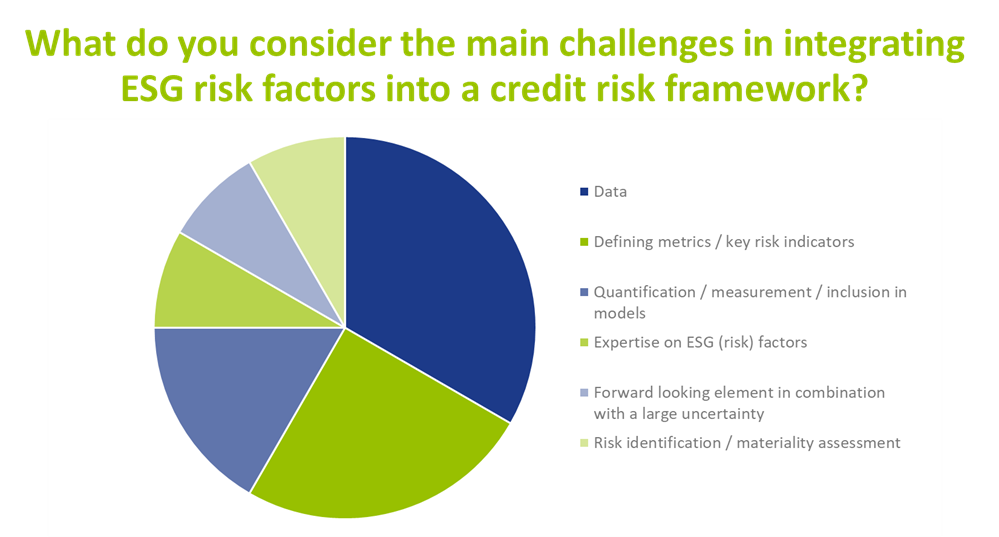

Currently, when it comes to incorporating ESG risks in the credit risk framework, banks are mainly focusing their attention on risk identification, the materiality assessment, risk metric definition and disclosures. The survey also reveals that the level of maturity with respect to ESG risk mitigation and risk limits differs significantly per bank. Nevertheless, the participating banks agreed that within one to three years, ESG risk factors are expected to be integrated in the key credit risk management processes, such as risk appetite setting, loan origination, pricing, and credit risk modeling. Data availability, defining metrics and the quantification of ESG risks were identified by banks as key challenges when integrating ESG in credit risk processes, as illustrated in the graph below.

In addition to the challenges mentioned above, discussion between participating banks revealed the following insights:

- Insight 1: Focus of ESG initiatives is on environmental factors. Most banks have started integrating environmental factors into their credit risk management processes. In contrast, efforts for integrating social and governance factors are far less advanced. Participants in the roundtable agreed that progress still has to be made in the area of data, definitions, and guidelines, before social and governance factors can be incorporated in a way that is similar to the approach for environmental factors.

- Insight 2: ESG adjustments to risk models may lead to double counting. The financial market still needs to gain more understanding to what extent ESG risk factor will manifest itself via existing risk drivers. For example, ESG factors such as energy label or flood risk may already be reflected in market prices for residential real estate. In that case, these ESG factors will automatically manifest itself via the existing LGD models and separate model adjustments for ESG may lead to double counting of ESG impact. Research so far shows mixed signals on this. For example, an analysis of housing prices by researchers from Tilburg University in 2021 has shown that there is indeed a price difference between similar houses with different energy labels. On the other hand, no unambiguous pricing differentiation was found as part of a historical house price analysis by economists from ABN AMRO in 2022 between similar houses with different flood risks. Participating banks agreed that further research and guidance from banks and the regulators is necessary on this topic.

- Insight 3: ESG factors may be incorporated in pricing. An outcome of incorporating ESG in a credit risk framework could be that price differentiation is introduced between loans that face high versus low climate risk. For example, consideration could be given to charging higher rates to corporates in polluting sectors or ones without an adequate plan to deal with the effects of climate change. Or to charge higher rates for residential mortgages with a low energy label or for the ones that are located in a flood-prone area. Participating banks agreed that in theory, price differentiation makes sense and most of them are investigating this option as a risk mitigating strategy. Nevertheless, some participants noted that, even if they would be able to perfectly quantify these risks in terms of price add-ons, they were not sure if and how (e.g., for which risk drivers and which portfolios) they would implement this. Other mitigating measures are also available, such as providing construction deposits to clients for making their homes more sustainable.

Conclusion

Most participating banks have made efforts to include ESG risk factors in their credit risk management processes. Nevertheless, many efforts are still required to comply with all regulatory expectations regarding this topic. Not only efforts by the banks themselves but also from researchers, regulators, and the financial market in general.

Zanders has already supported several banks and asset managers with the challenges related to integrating ESG risks into the risk organization. If you are interested in discussing how we can help your organization, please reach out to Sjoerd Blijlevens or Marije Wiersma.

Climate change risk

ESG-related derivatives: regulation & valuation

The Working Group II contribution to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report states that “climate change is a grave and mounting threat to our wellbeing and a healthy planet”. It is a formidable, global challenge to transition to a sustainable economy before time is running out. Banks have an important role to play in this transition. By stepping up to this role now, banks will be better prepared for the future, and reap the benefits along the way.

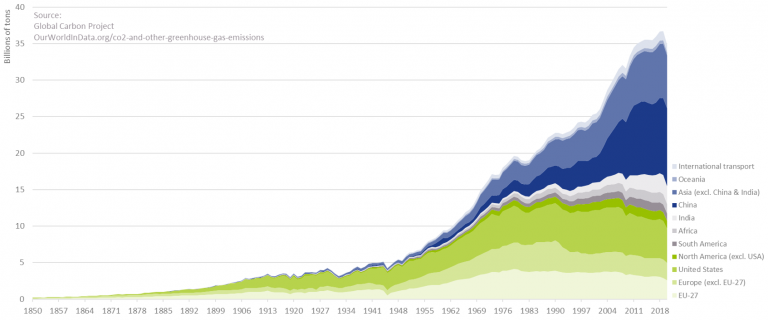

In the Paris Agreement (or COP21), adopted in December 2015, 196 parties agreed to limit global warming to well below 2.0°C, and preferably to no more than 1.5°C. To prevent irreversible impacts to our climate, the IPCC stresses that the increase in global temperature (relative to the pre-industrial era) needs to remain below 1.5°C. To achieve this target, a rapid and unprecedented decrease in the emission of greenhouse gasses (GHG) is required. With CO2 emissions still on the rise, as depicted in Figure 1, the challenge at hand has increased considerably in the past decade.

Figure 1 – Annual CO2 emissions from fossil fuels.

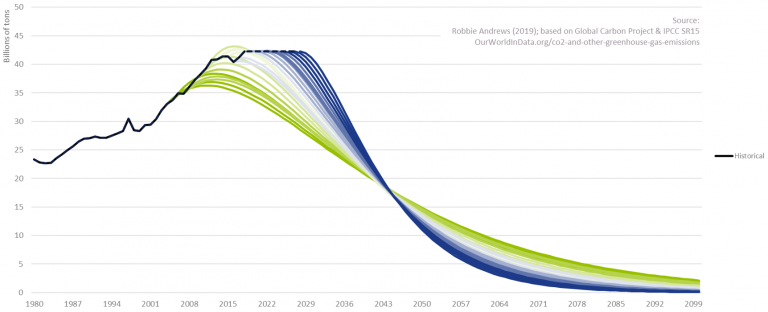

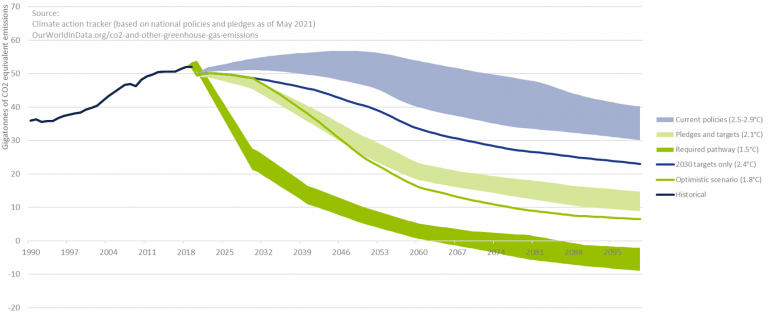

To further illustrate this, Figure 2 depicts for several starting years a possible pathway in CO2 reductions to ensure global warming does not exceed 2.0°C. Even under the assumption that CO2 emissions have already peaked, it becomes clear that the required speed of CO2 reductions is rapidly increasing with every year of inaction. We are a long way from limiting global warming to 2.0°C. This even holds under the assumption that all countries’ pledges to reduce GHG emissions will be achieved, as can be observed in Figure 3.

To quote the IPCC Working Group II co-chair Hans-Otto Pörtner: “Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all.”

Figure 2 – CO2 reduction need to limit global warming.

Figure 3 – Global GHG emissions and warming scenario’s.

The role of banks in the transition – and the opportunities it offers

Historically, banks have been instrumental to the proper functioning of the economy. In their role as financial intermediaries, they bring together savers and borrowers, support investment, and play an important role in facilitating payments and transactions. Now, banks have the opportunity to become instrumental to the proper functioning of the planet. By allocating their available capital to ‘green’ loans and investments at the expense of their ‘brown’ counterparts, banks can play a pivotal role in the transition to a sustainable economy. Banks are in the extraordinary position to make a fundamentally positive contribution to society. And even better, it comes with new opportunities.

The transition to a sustainable economy requires huge investments. It ranges from investments in climate change adaption to investments in GHG emission reductions: this covers for example investments in flood risk warning systems and financing a radical change in our energy mix from fossil-fuel based sources (like coal and natural gas) to clean energy sources (like solar and wind power). According to the Net Zero by 2050 Report from the International Energy Agency (IEA)2, the annual investments in the energy sector alone will increase from the current USD 2.3 trillion to USD 5.0 trillion by 2030. Hence, across sectors, the increase in annual investments could easily be USD 3.0 to 4.0 trillion. As much as 70% of this investment may need to be financed by the private sector (including banks and other financial institutions)3. To put this in perspective, the total outstanding credit to non-financial corporates currently stands at USD 86.3 trillion4. Assuming an average loan maturity of 5 years, this would translate to a 12-16% increase in loans and investments by banks on a global level. Hence, the transition to a sustainable economy will open up a large market for banks through direct investments and financing provided to corporates and households.

The transition to a sustainable economy is also triggering product development. The Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) for example reports that the combined issuance of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) bonds, sustainability-linked bonds and transition debt reached almost USD 500 billion in 2021H1, representing a 59% year-on-year growth rate. Other initiatives include the introduction of ‘green’ exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and sustainability-linked derivatives. The latter first appeared in 2019 and they provide an incentive for companies to achieve sustainable performance targets. If targets are met, a company is for example eligible for a more attractive interest coupon. Again, this is creating an interesting market for banks.

By embracing the transition, with all the opportunities that it offers, banks are also bracing themselves for the future. Banks that adopt climate change-resilient business models and integrate climate risk management into their risk frameworks will be much better positioned than banks that do not. They will be less exposed to climate-related risks, ranging from physical and transition risks to risks stemming from a reputational perspective or litigation, also justifying lower capital requirements. The early adaptors of today will be the leaders of tomorrow.

A roadmap supporting the transition

How should a bank approach this transition? As depicted in Figure 4, we identify four important steps: target setting, measurement and reporting, strategy and risk framework, and engaging with clients.

Figure 4 – The roadmap supporting the transition to a sustainable economy.

Target setting

The starting point for each transition is to set GHG emission targets in alignment with emission pathways that have been established by climate science. One important initiative that can support banks in setting these targets is the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). This organization supports companies to set targets in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Unlike many other companies, the majority of a bank’s GHG emissions are outside their direct control. They can influence, however, their so-called financed emissions, which are the GHG emissions coming from their lending and investment portfolios. The SBTi has developed a framework for banks that reflects this. It encourages banks to use the Absolute Contraction approach that requires a 2.5% (for a well-below 2.0°C target) or 4.2% (for a 1.5°C target) annual reduction in GHG emissions. A clear emission pathway guides banks in the subsequent steps of the transition process.

Measurement and reporting

With targets in place, the next important step for a bank is to determine their level of GHG emissions: both for scope 1 and 2 (the GHG emissions they control) and for scope 3 (the financed emissions). Important initiatives for the quantification of the financed emissions are the Paris Agreement Capital Transition Assessment (PACTA) and the Platform Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF). PCAF is a Dutch initiative to deliver a global, standardized GHG accounting and reporting approach for financial institutions (building on the GHG Protocol). PACTA enables banks to measure the alignment of financial portfolios with climate scenarios.

By keeping track of the level of GHG emissions on an annual basis, banks can assess whether they are following their selected emission pathway. Reporting, in line with the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), will contribute to a greater understanding of climate risks with their investors and other stakeholders.

Strategy and risk framework

Setting targets and measuring the current level of GHG emissions are necessary but not sufficient conditions to achieve a successful transition. Climate change risk needs to be fully integrated into a bank’s strategy and its risk framework. To assess the climate change-resilience of a bank’s strategy, a logical first step is to understand which climate change risks are material to the organization (e.g., by composing a materiality matrix). Subsequently, studying the transmission channels of these risks using scenario analysis and/or stress testing creates an understanding of what parts of the business model and lending portfolio are most exposed. This could lead to general changes in a bank’s positioning, but these risks should also be factored into the bank’s existing risk framework. Examples are the loan origination process, capital calculations, and risk reporting.

Engaging with clients

A fourth step in the game plan to successfully support the transition is for a bank to actively engage with its clients. A dialogue is required to align the bank’s GHG emission targets with those of its clients. This extends to discussing changes in the operations and/or business model of a client to align with a sustainable economy. This also may include timely announcing that certain economic activities will no longer be financed, and by financing client’s initiatives to mitigate or adapt to climate change: e.g., financing wind turbines for clients with energy- or carbon-intensive production processes (like cement or aluminium) or financing the move of production locations to less flood-prone areas.

Conclusion

Banks are uniquely positioned to play a pivotal role in the transition to a sustainable economy. The transition is already providing a wide range of opportunities for banks, from large financing needs to the introduction of green bonds and sustainability-linked derivatives. At the same time, it is of paramount importance for banks to adopt a climate change-resilient strategy and to integrate climate change risk into their risk frameworks. With our extensive track record in financial and non-financial risk management at financial institutions, Zanders stands ready to support you with this ambitious, yet rewarding challenge.

ESG risk management and Zanders

Zanders is currently supporting several clients with the identification, measurement, and management of ESG risks. For a start, we are supporting a large Dutch bank with the identification of ESG risk factors that have a material impact on the credit risk profile of its portfolio of corporate loans. The material risk factors are then integrated in the bank’s existing credit risk framework to ensure a proper management of this new risk type.

We are supporting other banking clients with the quantification of climate change risk. In one case, we are determining climate change risk-adjusted Probabilities of Default (PDs). Using expected future emissions and carbon prices based on the climate change scenarios of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), company specific shocks based on carbon prices and country specific shocks on GDP level are determined. These shocked levels are then used to determine the impact on the forecasted PDs. In another case, we are investigating the potential impact of floods and droughts on the collateral value of a portfolio of residential mortgage loans.

We also gained experience with the data challenges involved in the typical ESG project: e.g., we are supporting an asset manager with integrating and harmonizing ESG data from a range of vendors, which is underlying their internally developed ESG scores. We also support them with embedding these scores in the investment process.

With our extensive track record in financial and non-financial risk management at financial institutions in general, and our more recent ESG experience, Zanders stands ready to support you with the ambitious, yet rewarding challenge to adopt a climate change-resilient strategy and to integrate climate change risk in your existing risk frameworks.

Foot notes:

1 The IPCC Working Group II contribution: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

2 The IEA report, Net Zero by 2050.

3 See the Net Zero Financing roadmaps from the UN, ‘Race to Zero’ and the ‘Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero’ (GFANZ).

4 Based on the statistics of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) per 2021-Q3.

5 The Climate Bonds Initiative’s Sustainable Debt Highlights H1 2021.

EBA’s binding standards on Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks

On Thursday 9 June, we hosted a roundtable in our head office in Utrecht titled ’Integrating ESG risks into a bank’s credit risk framework’. The roundtable was attended by credit and climate risk managers, as well as model validators, working for Dutch banks of different sizes. In this article we briefly describe Zanders’ view on this topic and share the key insights of the roundtable.

This publication fits nicely into the ‘horizon priority’ of the EBA1 to provide tools to banks to measure and manage ESG-related risks. In this article we present a brief overview of the way the ITS have been developed, what qualitative and quantitative disclosures are required, what timelines and transitional measures apply – and where the largest challenges arise. By requiring banks to disclose information on their exposure to ESG-related risks and the actions they take to mitigate those risks – for example by supporting their clients and counterparties in the adaptation process – the EBA wants to contribute to a transition to a more sustainable economy. The Pillar 3 disclosure requirements apply to large institutions with securities traded on a regulated market of an EU member state.

In an earlier report2, the EBA defined ESG-related risks as “the risks of any negative financial impact on the institution stemming from the current or prospective impacts of ESG factors on its counterparties or invested assets”. Hence, the focus is not on the direct impact of ESG factors on the institution, but on the indirect impact through the exposure of counterparties and invested assets to ESG-related risks. The EBA report also provides examples for typical ESG-related factors.

While the ITS have been streamlined and simplified compared to the consultation paper published in March 2021, there are plenty of challenges remaining for banks to implement these standards.

Development of the ITS

The EBA has been mandated to develop the ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks in Article 434a of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). The EBA has opted for a sequential approach, with an initial focus on climate change-related risks. This is further narrowed down by only considering the banking book. The short maturity and fast revolving positions in the trading book are out of scope for now. The scope of the ITS will be extended to included other environmental risks (like loss of biodiversity), and social and governance risks, in later stages.

In the development of the ITS, the EBA has strived for alignment with several other regulations and initiatives on climate-related disclosures that apply to banks. The most notable ones are listed below (and in Figure 1):

Figure 1 – Overview of related regulations and initiatives considered in the development of the ITS

- Capital Requirements Directive and Regulation (CRD and CRR): article 98(8) of the CRD3 mandated the EBA to publish the EBA report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks, which includes the split of climate change-related risks in physical and transition risks. Article 434a of the CRR4 mandated the EBA to develop the draft ITS to specify the ESG disclosure requirements described in article 449a.

- EBA report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks2: the report provides common definitions of ESG risks and contains proposals on how to include ESG risks in the risk frameworks of banks, covering its identification, assessment, and management. It also discusses the way to include ESG risks in the supervisory review process.

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)5: the Financial Stability Board’s TFCD has published recommendations on climate-related disclosures. The metrics and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) included in the ITS have been aligned with the TCFD recommendations.

- Taxonomy Regulation6: the European Union’s common classification system of environmentally sustainable economic activities is underpinning the main KPIs introduced in the ITS.

- Climate Benchmark Regulation (CBR)7: In the CBR, two types of climate benchmarks were introduced (‘EU Climate Transition’ and ‘EU Paris-aligned’ benchmarks) and ESG disclosures for all other benchmarks (excluding interest rate and currency benchmarks) were required.

- Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD)8: the NFRD introduces ESG disclosure obligations for large companies, which include climate-related information.

- Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)9: a proposal by the European Commission to extend the scope of the NFRD to also include all companies listed on regulated markets (except listed micro-enterprises). One of the ITS’s KPIs, the Green Asset Ratio (GAR) is directly linked to the scope of the NFRD/CSRD.

- Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)10: the SFDR lays down sustainability disclosure obligations for manufacturers of financial products and financial advisers towards end-investors. It applies to banks that provide portfolio management investment advice services.

Compared to the consultation paper for the ITS, several changes have been made to the required templates. Some templates have been combined (e.g., templates #1 and #2 from the consultation paper have been combined into template #1 of the final draft ITS) and several templates have been reorganized and trimmed down (e.g., the requirement to report exposures to top EU or top national polluters has been removed).

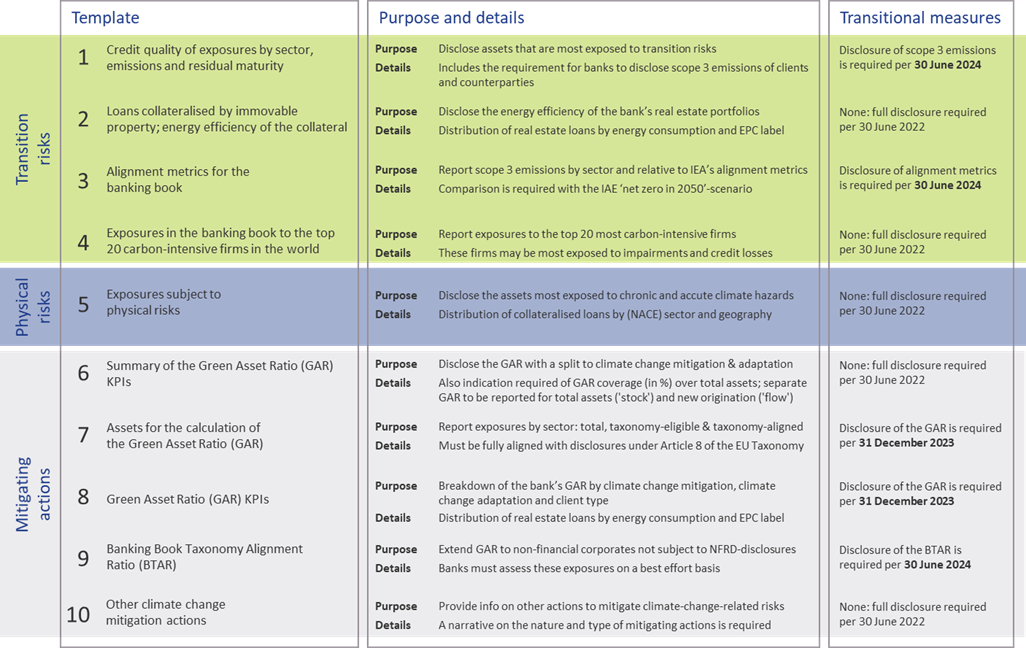

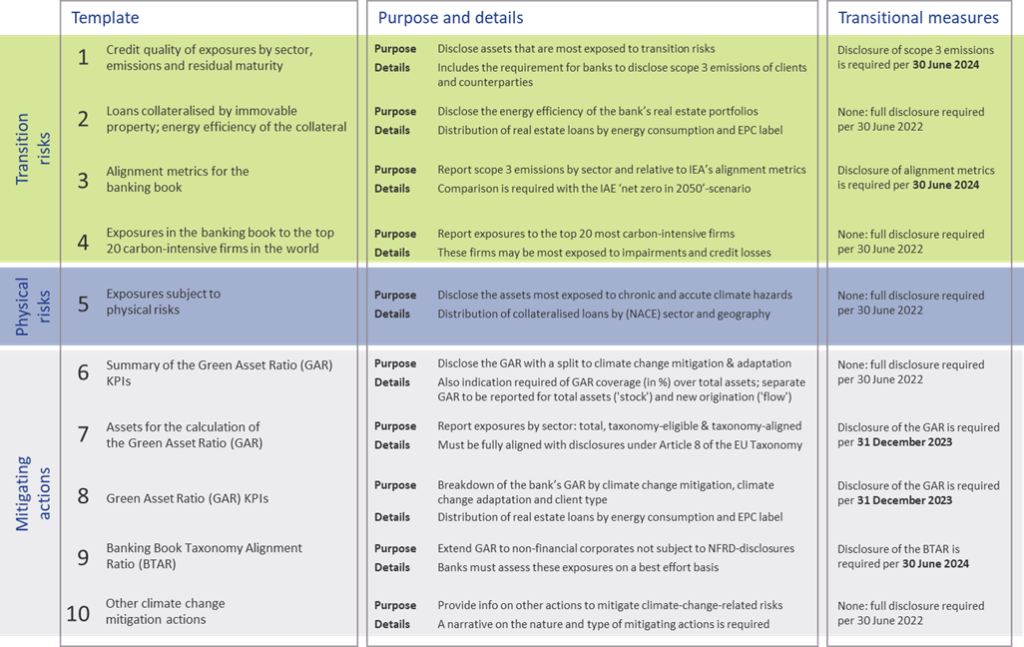

Quantitative disclosures

The ITS on P3 disclosure on ESG risks introduce ten templates on quantitative disclosures. These can be grouped in four templates on transition risks, one on physical risks, and five on mitigating actions:

- Transition risks

Two of the required templates are relatively straightforward. Banks need to report the energy efficiency of real estate collateral in the loan portfolio (#2) and report their aggregate exposure to the top 20 of the most carbon-intensive firms in the world (#4).

The main challenge for banks though will be in completing the other two templates:- Template #1 requires banks to disclose the gross carrying amount of loans and advances provided to non-financial corporates, classified by NACE sector codes and residual maturities. It is also required to report on the counterparties’ scope 1, 2, and 3 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Reflecting the challenge in reporting on scope 3 emissions, a transitional measure is in place. Full reporting needs to be in place by June 2024. Until then, banks need to report their available estimates (if any) and explain the methodologies and data sources they intend to use.

- In the last template (#3), banks also need to report scope 3 emissions, but relate these to the alignment metrics defined by the International Energy Agency (IEA) for the ‘net zero by 2050’ scenario. For this scenario, a target for a CO2 intensity metric is defined for 2030. By calculating the distance to this target, it becomes clear how banks are progressing (over time) towards supporting a sustainable economy. A similar transitional measure applies as for template #1.

- Physical risks

In template #5, banks are required to disclose how their banking book positions are exposed to physical risks, i.e., “chronic and acute climate-related hazards”. The exposures need to be reported by residual maturity and by NACE sector codes and should reflect exposure to risks like heat waves, droughts, floods, hurricanes, and wildfires. Specialized databases need to be consulted to compile a detailed understanding of these exposures. To support their submissions, banks further need to compile a narrative that explains the methodologies they used. - Mitigating actions

The final set of templates covers quantitative information on the actions a bank takes to mitigate or adapt to climate change risks.- Templates #6-8 all relate to the GAR, which indicates what part of the bank’s banking book is aligned with the EU’s Taxonomy:

- In template #7, banks need to report the outstanding banking book exposures to different types of clients/issuers, as well as the amount of these exposures that are taxonomy-eligible (that is, to sectors included in the EU Taxonomy) and taxonomy-aligned (that is, taxonomy-eligible exposures financing activities that contribute to climate change mitigation or adaptation). Based on this information, the bank’s GAR can be determined.

- In template #8, a GAR needs to be reported for the exposures to each type of client/issuer distinguished in template #7, with a distinction between a GAR for the full outstanding stock of exposures per client/issuer type, and a GAR for newly originated (‘flow’) exposures.

- Template #6 contains a summary of the GARs from templates #7 and #8.

In these templates, the numerator of the GAR only includes exposures to non-financial corporations that are required to publish non-financial information under the NFRD. Any exposures to other corporate counterparties therefore are considered 0% Taxonomy-aligned.

- The main challenge in this group of templates is in template #9. To incentivize banks to support all of their counterparties to transition to a more sustainable business model, and to collect ESG data on these counterparties, the EBA introduces the Banking Book Taxonomy Alignment Ratio (BTAR). In this metric, the numerator does include the exposures to counterparties that are not subject to NFRD disclosure obligations. The BTAR ratios obtained from the information in template #9 therefore complement the GAR ratios obtained in templates #7 and #8.

- In the final template (#10), banks have the opportunity to include any other climate change mitigating actions that are not covered by the EU Taxonomy. They can for example report on their use of green or sustainable bonds and loans.

- Templates #6-8 all relate to the GAR, which indicates what part of the bank’s banking book is aligned with the EU’s Taxonomy:

An overview of the templates for quantitative disclosures in presented in Figure 2.

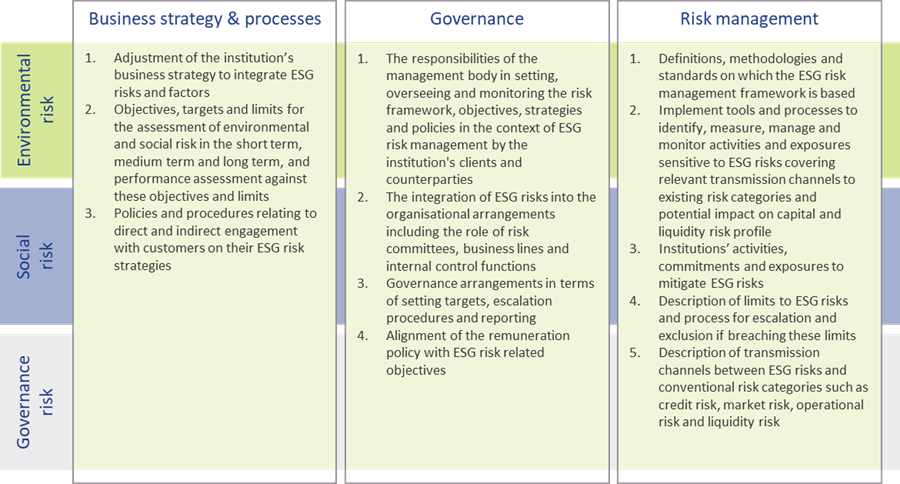

Qualitative disclosures

In the ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks, three tables are included for qualitative disclosures. The EBA has aligned these tables with their Report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks11. The three tables are set up for qualitative information on environmental, social, and governance risks, respectively. For each of these topics, banks need to address three aspects: on business strategy and processes, governance, and risk management. An overview of the required disclosures is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Overview of qualitative ESG disclosures (based on templates & section 2.3.2 of the EBA ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks)

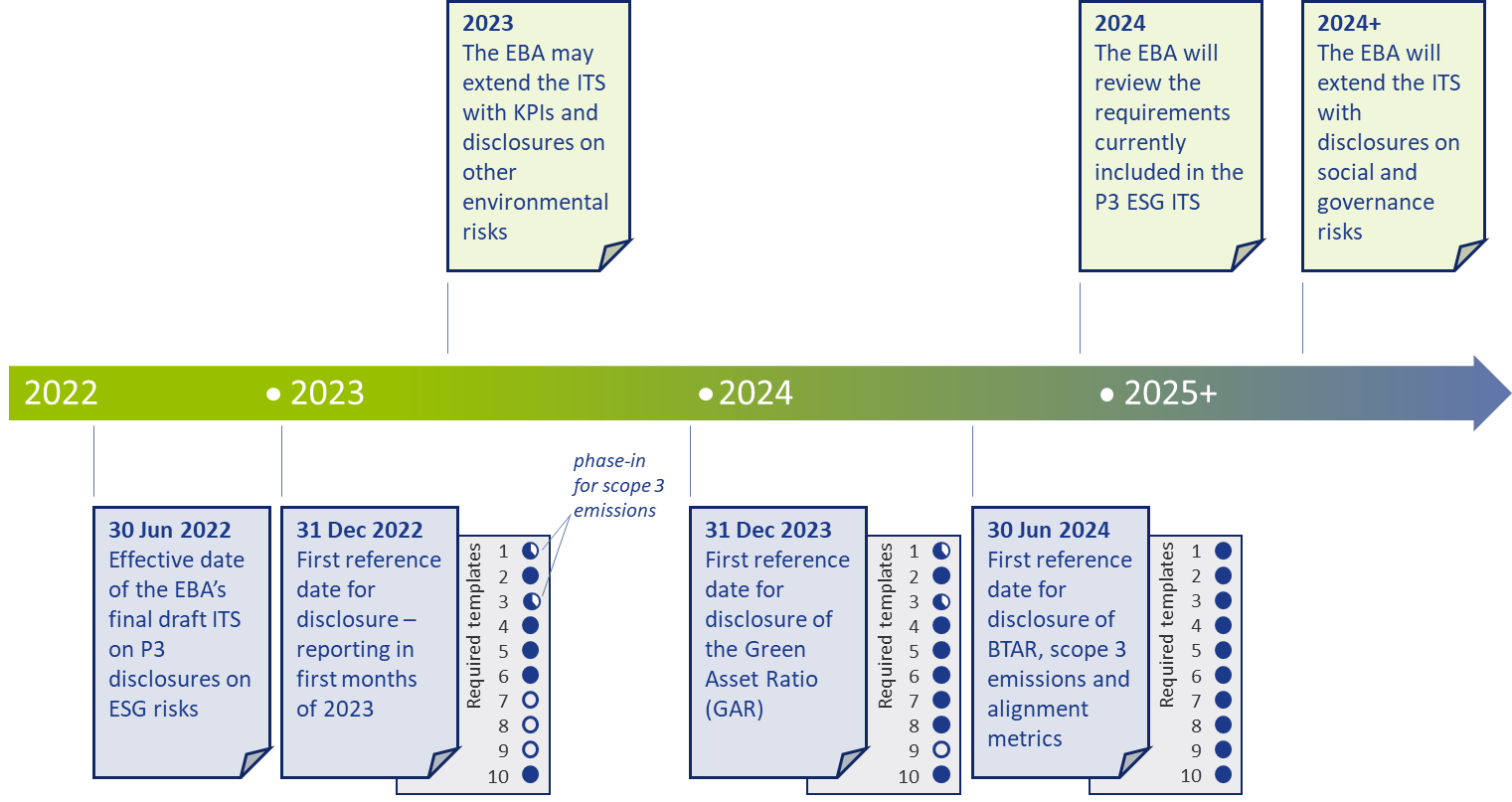

Timelines and transitional measures

The ITS on P3 disclosure on ESG risks become effective per 30 June 2022 for large institutions that have securities traded on a regulated market of an EU member state. A semi-annual disclosure is required, but the first disclosure is annual. Consequently, based on 31 December 2022 data, the first reporting will take place in the first quarter of 2023.

The EBA has introduced a number of transitional measures. These can be summarized as follows:

- The reporting of information on the GAR is only required as of 31 December 2023.

- The reporting of information on the BTAR, the bank’s financed scope 3 emissions, and the alignment metrics is only required as of June 2024.

The EBA has further indicated in the ITS that they will conduct a review of the ITS’s requirements during 2024. They may then also extend the ITS with other environmental risks (other than the climate change-related risks in the current version). The EU Taxonomy is expected to cover a broader range of environmental risks by the end of 2022. Sometime after 2024, it is expected that the EBA will further extend the ITS by including disclosure requirements on social and governance risks.

An overview of the main timelines and transitional measures is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Overview of the main timelines and transitional measures for the ESG disclosures

Conclusion

Society, and consequently banks too, are increasingly facing risks stemming from changes in our climate. In recent years, supervisory authorities have stepped up by introducing more and more guidance and regulation to create transparency about climate change risk, and more broadly ESG risks. The publication of the ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks by the EBA marks an important milestone. It offers banks the opportunity to disseminate a constructive and positive role in the transition to a sustainable economy.

Nonetheless, implementing the disclosure requirements will be a challenge. Developing detailed assessments of the physical risks to which their asset portfolio is exposed and to estimate the scope 3 emissions of their clients and counterparties (‘financed emissions’) will not be straightforward. For their largest counterparties, banks will be able to profit from the NFRD disclosure obligations, but especially in Europe a bank’s portfolio typically has many exposures to small- and medium-sized enterprises. Meeting the disclosure requirements introduced by the EBA will require timely and intensive discussions with a substantial part of the bank’s counterparties.

Banks also need to provide detailed information on how ESG risks are reflected in the bank’s strategy and governance and incorporated in the risk management framework. With our extensive knowledge on market risk, credit risk, liquidity risk, and business risk, Zanders is well equipped to support banks with integrating the identification, measurement, and management of climate change-related risks into existing risk frameworks. For more information, please contact Pieter Klaassen or Sjoerd Blijlevens via +31 88 991 02 00.

References

- See the EBA 2022 Work Programme.

- The EBA’s Report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks for credit institutions and investment firms, published in June 2021.

- See the EBA’s interactive Single Rulebook.

- See Regulation (EU) 2019/876.

- See the TCFD’s Final Report on Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures published in June 2017.

- See the EBA’s response to EC Call for Advice on Article 8 Taxonomy Regulation.

- See Regulation (EU) 2019/2089.

- See Directive 2014/95/EU.

- See the European Commission’s Proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

- See Regulation (EU) 2019/2088.

- The EBA report can be found here.

EBA’s binding standards on Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks

On Thursday 9 June, we hosted a roundtable in our head office in Utrecht titled ’Integrating ESG risks into a bank’s credit risk framework’. The roundtable was attended by credit and climate risk managers, as well as model validators, working for Dutch banks of different sizes. In this article we briefly describe Zanders’ view on this topic and share the key insights of the roundtable.

This publication fits nicely into the ‘horizon priority’ of the EBA to provide tools to banks to measure and manage ESG-related risks. In this article we present a brief overview of the way the ITS have been developed, what qualitative and quantitative disclosures are required, what timelines and transitional measures apply – and where the largest challenges arise.

By requiring banks to disclose information on their exposure to ESG-related risks and the actions they take to mitigate those risks – for example by supporting their clients and counterparties in the adaptation process – the EBA wants to contribute to a transition to a more sustainable economy. The Pillar 3 disclosure requirements apply to large institutions with securities traded on a regulated market of an EU member state.

In an earlier report2, the EBA defined ESG-related risks as “the risks of any negative financial impact on the institution stemming from the current or prospective impacts of ESG factors on its counterparties or invested assets”. Hence, the focus is not on the direct impact of ESG factors on the institution, but on the indirect impact through the exposure of counterparties and invested assets to ESG-related risks. The EBA report also provides examples for typical ESG-related factors.

While the ITS have been streamlined and simplified compared to the consultation paper published in March 2021, there are plenty of challenges remaining for banks to implement these standards.

Development of the ITS

The EBA has been mandated to develop the ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks in Article 434a of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). The EBA has opted for a sequential approach, with an initial focus on climate change-related risks. This is further narrowed down by only considering the banking book. The short maturity and fast revolving positions in the trading book are out of scope for now. The scope of the ITS will be extended to included other environmental risks (like loss of biodiversity), and social and governance risks, in later stages.

In the development of the ITS, the EBA has strived for alignment with several other regulations and initiatives on climate-related disclosures that apply to banks. The most notable ones are listed below (and in Figure 1):

Figure 1 – Overview of related regulations and initiatives considered in the development of the ITS

- Capital Requirements Directive and Regulation (CRD and CRR): article 98(8) of the CRD3 mandated the EBA to publish the EBA report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks, which includes the split of climate change-related risks in physical and transition risks. Article 434a of the CRR4 mandated the EBA to develop the draft ITS to specify the ESG disclosure requirements described in article 449a.

- EBA report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks2: the report provides common definitions of ESG risks and contains proposals on how to include ESG risks in the risk frameworks of banks, covering its identification, assessment, and management. It also discusses the way to include ESG risks in the supervisory review process.

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)5: the Financial Stability Board’s TFCD has published recommendations on climate-related disclosures. The metrics and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) included in the ITS have been aligned with the TCFD recommendations.

- Taxonomy Regulation6: the European Union’s common classification system of environmentally sustainable economic activities is underpinning the main KPIs introduced in the ITS.

- Climate Benchmark Regulation (CBR)7: In the CBR, two types of climate benchmarks were introduced (‘EU Climate Transition’ and ‘EU Paris-aligned’ benchmarks) and ESG disclosures for all other benchmarks (excluding interest rate and currency benchmarks) were required.

- Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD)8: the NFRD introduces ESG disclosure obligations for large companies, which include climate-related information.

- Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)9: a proposal by the European Commission to extend the scope of the NFRD to also include all companies listed on regulated markets (except listed micro-enterprises). One of the ITS’s KPIs, the Green Asset Ratio (GAR) is directly linked to the scope of the NFRD/CSRD.

- Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)10: the SFDR lays down sustainability disclosure obligations for manufacturers of financial products and financial advisers towards end-investors. It applies to banks that provide portfolio management investment advice services.

Compared to the consultation paper for the ITS, several changes have been made to the required templates. Some templates have been combined (e.g., templates #1 and #2 from the consultation paper have been combined into template #1 of the final draft ITS) and several templates have been reorganized and trimmed down (e.g., the requirement to report exposures to top EU or top national polluters has been removed).

Quantitative disclosures

The ITS on P3 disclosure on ESG risks introduce ten templates on quantitative disclosures. These can be grouped in four templates on transition risks, one on physical risks, and five on mitigating actions:

- Transition risks

Two of the required templates are relatively straightforward. Banks need to report the energy efficiency of real estate collateral in the loan portfolio (#2) and report their aggregate exposure to the top 20 of the most carbon-intensive firms in the world (#4).

The main challenge for banks though will be in completing the other two templates:- Template #1 requires banks to disclose the gross carrying amount of loans and advances provided to non-financial corporates, classified by NACE sector codes and residual maturities. It is also required to report on the counterparties’ scope 1, 2, and 3 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Reflecting the challenge in reporting on scope 3 emissions, a transitional measure is in place. Full reporting needs to be in place by June 2024. Until then, banks need to report their available estimates (if any) and explain the methodologies and data sources they intend to use.

- In the last template (#3), banks also need to report scope 3 emissions, but relate these to the alignment metrics defined by the International Energy Agency (IEA) for the ‘net zero by 2050’ scenario. For this scenario, a target for a CO2 intensity metric is defined for 2030. By calculating the distance to this target, it becomes clear how banks are progressing (over time) towards supporting a sustainable economy. A similar transitional measure applies as for template #1.

- Physical risks

In template #5, banks are required to disclose how their banking book positions are exposed to physical risks, i.e., “chronic and acute climate-related hazards”. The exposures need to be reported by residual maturity and by NACE sector codes and should reflect exposure to risks like heat waves, droughts, floods, hurricanes, and wildfires. Specialized databases need to be consulted to compile a detailed understanding of these exposures. To support their submissions, banks further need to compile a narrative that explains the methodologies they used. - Mitigating actions

The final set of templates covers quantitative information on the actions a bank takes to mitigate or adapt to climate change risks.- Templates #6-8 all relate to the GAR, which indicates what part of the bank’s banking book is aligned with the EU’s Taxonomy:

- In template #7, banks need to report the outstanding banking book exposures to different types of clients/issuers, as well as the amount of these exposures that are taxonomy-eligible (that is, to sectors included in the EU Taxonomy) and taxonomy-aligned (that is, taxonomy-eligible exposures financing activities that contribute to climate change mitigation or adaptation). Based on this information, the bank’s GAR can be determined.

- In template #8, a GAR needs to be reported for the exposures to each type of client/issuer distinguished in template #7, with a distinction between a GAR for the full outstanding stock of exposures per client/issuer type, and a GAR for newly originated (‘flow’) exposures.

- Template #6 contains a summary of the GARs from templates #7 and #8.

In these templates, the numerator of the GAR only includes exposures to non-financial corporations that are required to publish non-financial information under the NFRD. Any exposures to other corporate counterparties therefore are considered 0% Taxonomy-aligned.

- The main challenge in this group of templates is in template #9. To incentivize banks to support all of their counterparties to transition to a more sustainable business model, and to collect ESG data on these counterparties, the EBA introduces the Banking Book Taxonomy Alignment Ratio (BTAR). In this metric, the numerator does include the exposures to counterparties that are not subject to NFRD disclosure obligations. The BTAR ratios obtained from the information in template #9 therefore complement the GAR ratios obtained in templates #7 and #8.

- In the final template (#10), banks have the opportunity to include any other climate change mitigating actions that are not covered by the EU Taxonomy. They can for example report on their use of green or sustainable bonds and loans.

- Templates #6-8 all relate to the GAR, which indicates what part of the bank’s banking book is aligned with the EU’s Taxonomy:

An overview of the templates for quantitative disclosures in presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Overview of the required quantitative ESG disclosures

Qualitative disclosures

In the ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks, three tables are included for qualitative disclosures. The EBA has aligned these tables with their Report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks11. The three tables are set up for qualitative information on environmental, social, and governance risks, respectively. For each of these topics, banks need to address three aspects: on business strategy and processes, governance, and risk management. An overview of the required disclosures is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Overview of qualitative ESG disclosures (based on templates & section 2.3.2 of the EBA ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks)

Timelines and transitional measures

The ITS on P3 disclosure on ESG risks become effective per 30 June 2022 for large institutions that have securities traded on a regulated market of an EU member state. A semi-annual disclosure is required, but the first disclosure is annual. Consequently, based on 31 December 2022 data, the first reporting will take place in the first quarter of 2023.

The EBA has introduced a number of transitional measures. These can be summarized as follows:

- The reporting of information on the GAR is only required as of 31 December 2023.

- The reporting of information on the BTAR, the bank’s financed scope 3 emissions, and the alignment metrics is only required as of June 2024.

The EBA has further indicated in the ITS that they will conduct a review of the ITS’s requirements during 2024. They may then also extend the ITS with other environmental risks (other than the climate change-related risks in the current version). The EU Taxonomy is expected to cover a broader range of environmental risks by the end of 2022. Sometime after 2024, it is expected that the EBA will further extend the ITS by including disclosure requirements on social and governance risks.

An overview of the main timelines and transitional measures is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Overview of the main timelines and transitional measures for the ESG disclosures

Conclusion

Society, and consequently banks too, are increasingly facing risks stemming from changes in our climate. In recent years, supervisory authorities have stepped up by introducing more and more guidance and regulation to create transparency about climate change risk, and more broadly ESG risks. The publication of the ITS on P3 disclosures on ESG risks by the EBA marks an important milestone. It offers banks the opportunity to disseminate a constructive and positive role in the transition to a sustainable economy.

Nonetheless, implementing the disclosure requirements will be a challenge. Developing detailed assessments of the physical risks to which their asset portfolio is exposed and to estimate the scope 3 emissions of their clients and counterparties (‘financed emissions’) will not be straightforward. For their largest counterparties, banks will be able to profit from the NFRD disclosure obligations, but especially in Europe a bank’s portfolio typically has many exposures to small- and medium-sized enterprises. Meeting the disclosure requirements introduced by the EBA will require timely and intensive discussions with a substantial part of the bank’s counterparties.

Banks also need to provide detailed information on how ESG risks are reflected in the bank’s strategy and governance and incorporated in the risk management framework. With our extensive knowledge on market risk, credit risk, liquidity risk, and business risk, Zanders is well equipped to support banks with integrating the identification, measurement, and management of climate change-related risks into existing risk frameworks. For more information, please contact Pieter Klaassen or Sjoerd Blijlevens via +31 88 991 02 00.

References

1) See the EBA 2022 Work Programme.

2) The EBA’s Report on Management and Supervision of ESG risks for credit institutions and investment firms, published in June 2021.

3) See the EBA’s interactive Single Rulebook.

4) See Regulation (EU) 2019/876.

5) See the TCFD’s Final Report on Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures published in June 2017.

6) See the EBA’s response to EC Call for Advice on Article 8 Taxonomy Regulation.

7) See Regulation (EU) 2019/2089.

8) See Directive 2014/95/EU.

9) See the European Commission’s Proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

10) See Regulation (EU) 2019/2088.

11) The EBA report can be found here.

Climate Change Risk Management for insurers.

ESG-related derivatives: regulation & valuation

Climate change risks are relatively newly identified risks that insurers are facing. These risks can negatively impact both assets and liabilities of insurers. Already in 2018, the European Commission requested the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) to investigate how climate change risk could be integrated into the Solvency II Framework.

After various previous publications1 of (draft) opinions, the investigation resulted in EIOPA’s opinion to include climate change risk scenarios in Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA)2. It basically points out that forward-looking management of climate change risks is essential, and that EIOPA expects insurers to integrate climate change risk scenarios in their ORSA. EIOPA indicates it will start monitoring the application of this opinion two years after publication, i.e. as of April 2023. However, some National Competent Authorities already require insurers to take climate change risks into account.3

So, what will be expected of insurers?

In general terms, insurers are expected to:

- Integrate climate change risks in their system of governance, risk management system and ORSA

- Assess climate change risk in ORSA in the short and long term

- Disclose climate-related information

But what does this mean in practice? We will further explained this per topic.

Integrating climate change risks