The EBA published its roadmap the implementation of Basel and starts with the first consultations

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union. This roadmap develops over four phases, and it is expected to be completed as follows:

- Phase 1: Covers 32 mandates in the areas of credit, market and operational risk, which predominantly result from the transition to Basel III. In addition, this first phase will also see the first mandates under the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) in the area of ESG.

- Phase 2: This phase will further progress in covering Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) mandates related to credit, operational and market risk. Furthermore, a considerable number of CRD mandates related to high EU standards in terms of governance and access to the single market with regard to third-country branches will be developed in this phase.

- Phase 3: It includes most of the remaining mandates related to regulatory products as well as a number of reports, whereby further perspectives and initial monitoring efforts regarding banking regulation implementation are worth considering.•

- Phase 4: In this last phase, a number of products, mostly consisting of reports, will be developed, providing information on the implementation progress, results and challenges.

In addition, there are some mandates that are ongoing and reoccurring and are not part of any of the four phases but will be made operational at the date of implementation in 2025. As part of phase 1, the EBA has published multiple consultation papers, which form the first step in the implementation of the Banking Package. The three main consultation papers published are:

- A public consultation on two draft ITS amending Pillar 3 disclosure requirements and supervisory reporting requirements. The suggested amendments on the reporting obligations cover a wide range of topics such as the output floor, standardized and internal ratings-based models (IRB) for credit risk, the three new approaches for own funds requirements for CVA risk and the (simplified) standardized approach for market risk.

- A public consultation launched by the EBA on the Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS) determining the conditions for an instrument with residual risk to be classified as a hedge. This consultation, on the standardized approach under the FRTB framework, focuses on the residual risk add-on (RRAO). Introduced by the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR3), the RRAO framework allows exemptions for instruments hedging residual risks. The proposed RTS outline criteria for identifying hedges, distinguishing between non-sensitivity-based method risk factors and other reasons for RRAO charges.

- A public consultation on two draft Implementing Technical Standards (ITS) amending Pillar 3 disclosures and supervisory reporting requirements for operational risk. These revisions align with the new Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR3) and aim to consolidate reporting and disclosure requirements for operational risk and broader CRR3 changes. These consultation papers should be read in conjunction with the consultation papers on the new framework for the business indicator for operational risk, published at the same time.

Model Risk Management – Expanding quantification of model risk

Model risk from risk models has become a focal point of discussion between regulators and the banking industry.

Model risk from risk models has become a focal point of discussion between regulators and the banking industry. As financial institutions strive to enhance their model risk management practices, the need for robust model risk quantification becomes paramount.

An introduction to model risk quantification

Many firms already have comprehensive model risk management frameworks that tier models using an ordinal rating (such as high/medium/low risk). However, this provides limited information on potential losses due to model risk or the capital cost of already identified model risks. Model risk quantification uses quantitative techniques to bridge this gap and calculate the potential impact of model risk on a business.

The goal of a model risk quantification framework

As with many other sources of risk within a financial institute, the aim is to manage risk by holding capital against potential losses from the use of individual models across the firm. This can be achieved by including model risk as a component of Pillar 2 within the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP).

Key components of a quantification framework

An effective model risk quantification framework should be:

- Risk-based: By utilising model tiering results to identify models with risk worth the cost of quantifying.

- Process driven: By providing a system for identifying, measuring and classifying the impact of model risks.

- Aggregable: By producing results that can be aggregated and including a methodology for aggregating model results to a firm level.

- Transparent & capitalised: By regularly reporting aggregated firm-wide model risk and managing it using capitalisation.

Blockers impeding model risk quantification

Complications of quantification include:

- Implementation and running costs: Setting up and regularly running any quantification test involves significant resource costs.

- Uncovered risk: Trying to quantify all potential model risk is a Sisyphean task.

- Internal resistance: Quantification and capitalisation of model risks will require increased resources to produce, leading to higher costs, making it a hard initiative to motivate individuals to follow.

Concepts in Model Risk Quantification

Impacts of Model Risk

Model risk significantly influences financial institutions through valuations, capital requirements, and overall risk management strategies. The uncertainties tied to model outcomes can have profound impacts on regulatory compliance, economic capital, and the firm's standing in the financial ecosystem.

Model tiering

Model tiering is a qualitative exercise that assesses the holistic risk of a model by considering various factors (e.g. materiality, importance, complexity, transparency, operational intricacies, and controls).

The tiering output grades the risk of a model on an ordinal scale, comparing it to other models within the institute. However, it doesn't provide a quantitative metric that can be aggregated with other models.

Overlap with quantitative regulations

Most firms already perform quantitative processes to measure the performance of Pillar 1 models that impact the regulatory capital held (such as the VaR backtesting multiplier applied to market risk RWA).

Model Risk Quantification Framework - The Model Uncertainty Approach

A crucial step in building a robust model risk quantification framework is classifying and assessing the impact of model risk. The model uncertainty approach is an internal quantitative approach in which model risks are identified and quantified on an individual level. Individual model risks are subsequently aggregated and translated into a monetary impact on the bank.

Regulatory Model Risk Quantificaiton Methods - RNIV, Backtesting Multiplier, Prudent Valuation and MoC

Most banks are already familiar with quantification techniques recommend by regulators for risk management. Below we highlight some of these techniques that can be used as the basis for expansion of quantification within a firm.

Expanding Model Risk Quantification

Our approach to efficient measurement relies on two key components. The first is model risk classifications to prioritize models to quantify, and the second is a knowledge base of already implemented regulatory and internally developed techniques to quantify that risk. This approach provides good risk coverage whilst also being extremely resource efficient.

Looking to learn more about Model Risk Management? Reach out to our experts Dr. Andreas Peter, Alexander Mottram, Hisham Mirza.

Six years after the introduction of IFRS 9: Where do we stand?

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

We touch upon the main difficulties experienced by financial institutions in the Netherlands based on a combination of project experience, results of a survey, main attention points from the eyes of the regulator and observations from publicly available annual reports. Interested to learn more about the IFRS 9 framework components banks struggle with the most and whether these challenges can be easily solved? Find out in the remainder of this article.

Introduction

The main objective of this article is to provide insight into market practices and common challenges within the IFRS 9 landscape of Dutch financial institutions. In this light, Zanders conducted a survey amongst Dutch financial institutions. Six main IFRS 9 framework components form the basis of the survey: data quality, model components (PD, LGD, EAD), SICR & staging, macroeconomic scenarios, out-of-model adjustments and the relation between IFRS 9 and other models within the bank. An example of a full IFRS 9 framework overview is presented in Figure 1. The questionnaire was followed up by a roundtable in which the most noticeable results from the survey were discussed with the participants.

Besides the survey, the IFRS 9 monitoring report published by the European Banking Authority (IFRS 9 Monitoring report, EBA (November 2023)) provides insights into the key IFRS 9 attention points from a regulatory perspective (e.g. as identified by EBA). In this article, we discuss the key differences between the difficulties experienced by banks versus attention points highlighted in the monitoring report. Lastly, this article uses publicly available information from annual reports to illustrate the diverging modelling practices and model behavior amongst market peers.

Figure 1: IFRS 9 framework overview.

Survey

The IFRS 9 survey held in Q4 2023 was centered around the six framework components as stated in the introduction section and which are graphically presented in Figure 1. The participating banks were asked in which areas of the framework they experience difficulties. Consequently, each area was explored deeper by means of questions directly related to each area.

All participating banks except one indicate difficulties in the areas of data quality and out-of-model adjustments (e.g. overlays). For data quality, changing policies (e.g. Definition of Default, loan quality assessment), limited loss realizations for LGD (as well as limited detail of the loss realization data) and dealing with unrepresentative data from the Covid-19 period are examples of reasons for the difficulties experienced in this area. With regards to out-of-model adjustments, it becomes apparent that many banks struggle with pressure from the regulator and audit, triggering banks to find an escape in overlays on the IFRS 9 model outcomes. Overlays are applied on a wide variety of topics, in various ways (e.g. calculated, constant, periodic, expert based, etc.) and sometimes constitute the majority of the total provisions. Altogether, this illustrates the need to have out-of-model adjustments in place that are sufficiently qualitatively substantiated and, whenever possible, are applied on the model component level. At the same time, we are of the opinion that out-of-model adjustments are sometimes over-used to make up for model deficiencies. Especially when out-of-model adjustments constitute the majority of the total provisions, compliance of the model with the IFRS 9 best-estimate principle should be questioned.

Surprisingly, only one third of the respondents experiences difficulties in the framework areas that came into existence with the introduction of IFRS 9; SICR & staging and macroeconomic scenarios. A possible explanation for this is that the responsibility for these framework areas is often distributed across multiple departments. Macroeconomic predictions and scenario weights are usually determined by a separate macroeconomic scenario department or committee, and staging assessments are often placed outside the scope of IFRS 9 modelling teams. From a governance perspective, we are of the opinion that more alignment over the full IFRS 9 provisioning chain is desired.

Want to know more about the survey results? Download our white paper.

Regulatory view

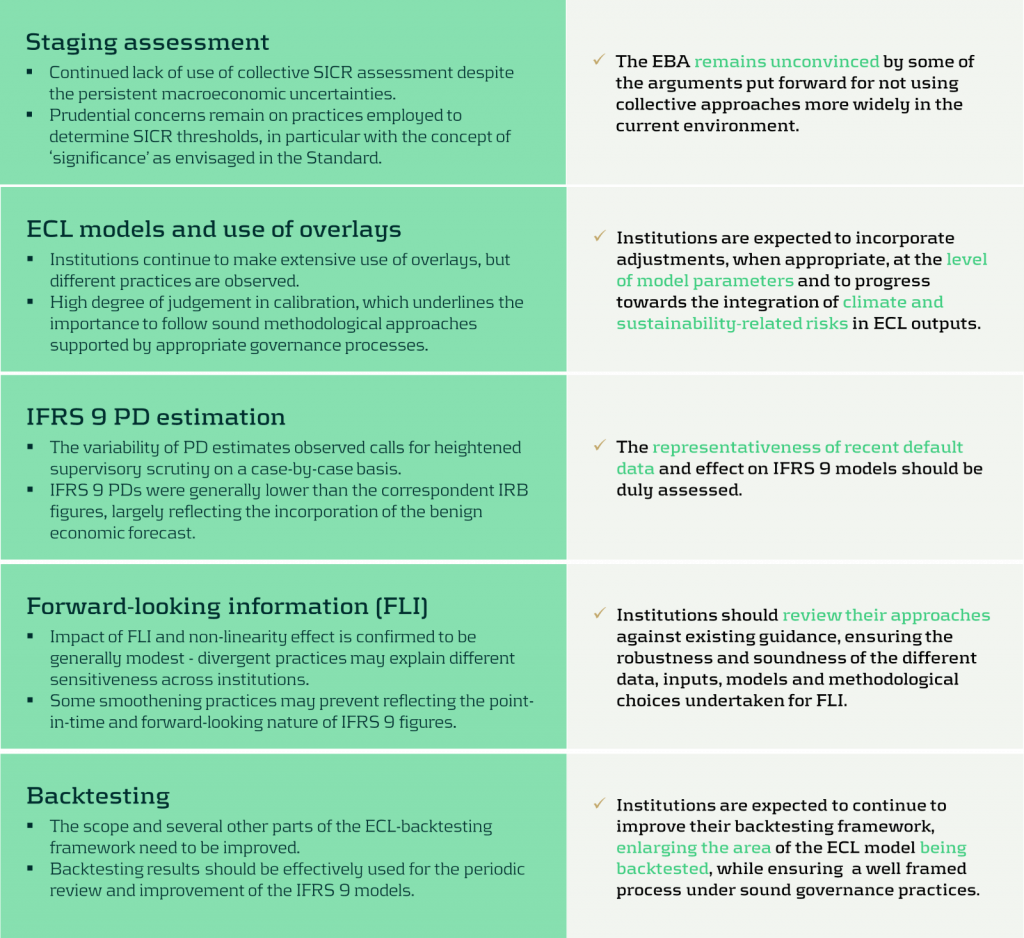

The EBA published a monitoring report in November 2023 on the current status of the IFRS 9 model landscape (IFRS 9 Monitoring report, EBA (November 2023)). In this report the EBA highlights several takeaways, which are shown in Figure 2. One of these takeaways is the manner in which SICR is modelled at the moment. The EBA is not convinced that non-collective approaches are more suitable than collective approaches. In the results of the survey however, it was shown that most respondents did not indicate SICR as one of the main challenges in their IFRS 9 landscape. This raises the question whether banks in the Netherlands are aware of the EBA’s remark on the current SICR approaches, or whether Dutch banks are outliers when it comes to the SICR modelling approaches.

Furthermore, the report indicates that out-of-model adjustments should be applied on the model parameter level and not on the outcome level. During the roundtable it was discussed that several participants recognize this desire from the regulator, but that they still apply it on the outcome level because the available data only allows for this level. This discrepancy could lead to further scrutiny from the regulator in the near future.

Figure 2: Key takeaways from the IFRS 9 monitoring report (EBA, 2023).

Annual report study

In the Dutch banking market, a variety of modelling practices is observed when it comes to IFRS 9 models for calculating credit loss provisions. Besides gaining insights into these IFRS 9 modelling practices via a survey, annual reports are analyzed to identify potential differences (or similarities) from information that is publicly available.

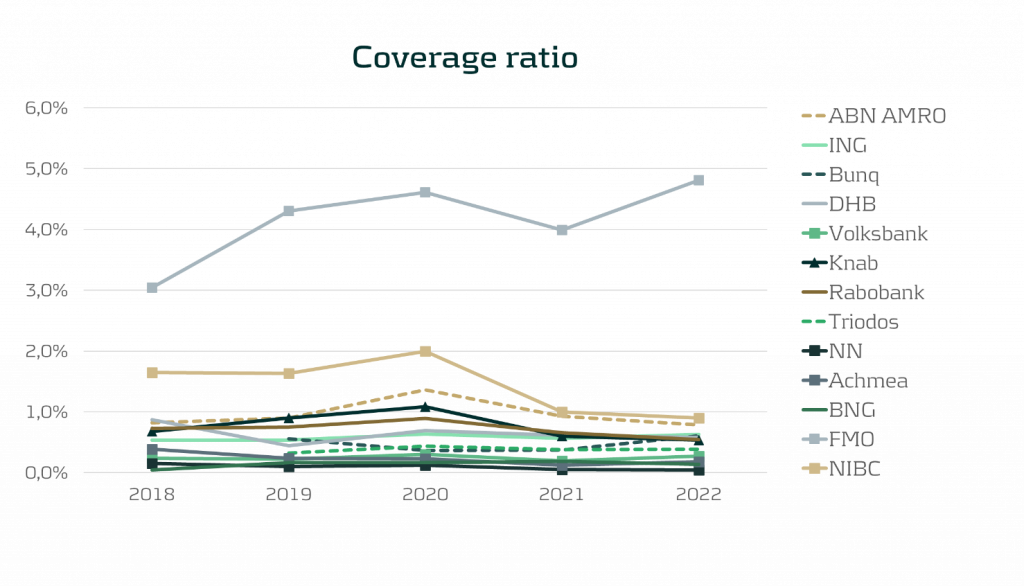

One of the observations from comparing annual reports is that no common level is observed for the Provisioning Coverage Ratio (PCR), i.e. the percentage of funds set aside for covering losses due to bad debts. Characteristics such as portfolio type/composition and loan maturity likely explain these differences. In 2020, almost all banks show an increase in the PCR due to increased allowances in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Note that this was not necessarily caused by models picking up changing macroeconomic dynamics, but because of model overlays. PCR levels stabilized again in 2021 and 2022.

Figure 3: Coverage ratio over the years 2018 till 2022 . All results were gathered from public annual reports.

Although not all banks report macroeconomic scenario weights in their annual reports, it is worth noting that large differences exist in the scenario weights of banks that do report these figures. Especially weights assigned to the up and down scenarios vary significantly. In 2022, the weight percentage for the base scenario is generally between 40% and 60% (one bank uses a weight of 30%), whereas the weight percentage for the down scenario ranges from 20% to 60%. For the up scenario, percentage weights differ from 2% to 30%. It must be noted that the scenario weights cannot be judged without considering the actual scenario definitions/severity. Nonetheless, the wide variety in scenario weight percentages as well as large differences in the development of these scenario weights over time raises questions on the accuracy of macroeconomic predictions. In addition, it also complicates the comparability of IFRS 9 figures amongst banks.

What can Zanders offer?

We combine deep credit risk modelling expertise with relevant experience in regulation and programming:

- A Risk Advisory Team consisting of 75+ consultants with quantitative backgrounds (e.g. Econometrics and Physics);

- Strong knowledge of IFRS 9 models and developments in the IFRS 9 landscape;

- Extensive experience with calibration, implementation and validation of IFRS 9 models;

- We offer ready-to-use Expected Credit Loss models, Credit Risk Academy modules and expert sessions that can be tailored to the needs of your organization.

Interested to learn more? Contact Kasper Wijshoff or Michiel Harmsen for questions on IFRS 9.

Environmental and social risks in the prudential framework: Possible implications for banks

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

In October 2023, the European Banking Authority (EBA) published a report[1] with recommendations for enhancements to the Pillar 1 prudential framework to reflect environmental and social (E&S) risks, distinguishing between actions to be taken in the short term and in the medium to long term. The short-term actions are to be taken into account over the next three years as part of the implementation of the revised Capital Requirements Regulation and Capital Requirements Directive (CRR3/CRD6).

The EBA report follows a discussion paper on the same topic from May 2022[2], on which it solicited input from the financial industry. In this note, we provide an overview of the recommended actions by the EBA that relate to the prudential framework for banks. The EBA report also contains recommended actions for the prudential framework applying to investment firms, but these are not addressed here.

If the EBA’s recommendations are implemented in the prudential framework, in our view the most immediate implications for banks would be:

- When using external ratings to determine own fund requirements for credit risk under the standardized approach (SA) of Pillar 1, ensure that E&S risks are explicitly considered when evaluating the appropriateness of the external ratings as part of the due diligence requirements.

- When calculating own fund requirements for credit risk under the internal-ratings-based (IRB) approach, embed E&S risks in the rating assignment, risk quantification (for example through a margin of conservatism or the downturn component) and/or expert judgment and overrides.

- To assess E&S risks at a borrower level, establish a process to obtain and update material E&S-related information on the borrowers’ financial condition and credit facility characteristics, as part of due diligence during onboarding and ongoing monitoring of the borrowers’ risk profile.

- For IRB banks, embed E&S risks in the credit risk stress testing programs.

- Ensure that E&S risks are considered in the valuation of collateral, specifically for financial and real estate collateral.

- For market risk, embed environmental risks in trading book risk appetite, internal trading limits and the new product approval process. Furthermore, for banks aiming to use the internal model approach (IMA) of the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) regulation, environmental risks need to be considered in their stress testing program.

- For operational risk, identify whether E&S risks constitute triggers of operational risk losses.

We note that many of these implications align with the ECB’s expectations in the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks[3].

Background

The EBA report considers both environmental and social risks, which the EBA characterizes as follows:

- As drivers of environmental risks, EBA distinguishes physical and transition (climate) risks. It does not explicitly refer in the report to other environmental risks, such as a loss of biodiversity or pollution, but in an earlier report the EBA considered these as part of chronic physical risks[4].

- EBA considers social factors to be related to the rights, well-being and interests of people and communities, including factors such as decent work, adequate living standards, inclusive and sustainable communities and societies, and human rights. As drivers of social risks, EBA distinguishes environmental factors (as materialization of physical and transition risks may change living standards and the labor market and increase social tensions, for example) as well as changes in policies and market sentiment. These may in part be driven by actions taken to meet the United Nation’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) in 2030.

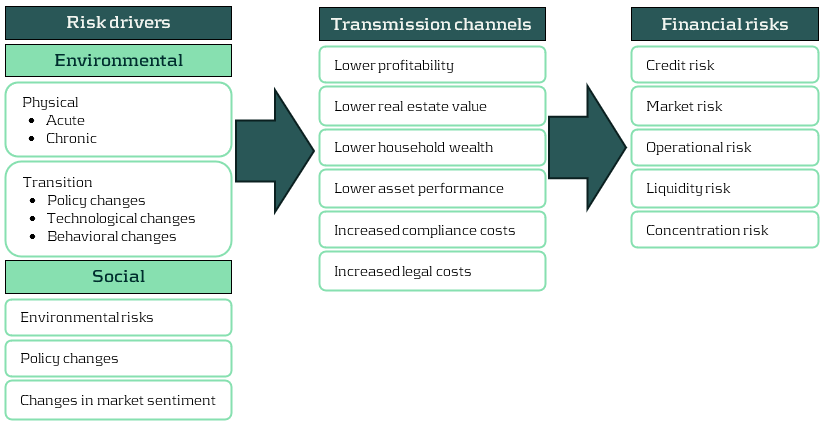

In line with the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks[5], the EBA does not view E&S risks as stand-alone risks, but as drivers of traditional banking risks. This is depicted in Figure 1. The report considers the impact on credit, market, operational, liquidity and concentration risks and reviews to what extent E&S risks can be reflected in capital buffers and the macro-prudential framework. It does not explicitly consider the securitization framework, although this will be implicitly affected by impacts on credit risk. The EBA does not see an impact of E&S risks on the (risk-insensitive) leverage ratio, and therefore does not consider it in the report.

Figure 1: Examples of transmission channels for environmental and social risks (source: EBA).

The EBA notes that the Pillar 1 framework has been designed to capture the possible financial impact of cyclical economic fluctuations, but not to capture the manifestation of long-term environmental risks. It is therefore important to keep the main principles that form the basis of the prudential framework in mind when contemplating adjustments to reflect E&S risks in the prudential framework. The main principles as highlighted by the EBA are summarized below.

Main principles of the prudential framework and the relation to the horizon for E&S risks

With repect to the framework in general:

- Own fund requirements are intended to cover potential unexpected losses. In contrast, expected losses are directly deducted from own funds, and are generally captured in the accounting rules through provisions, impairments, write-downs and appropriate valuation of assets.

- The purpose of own fund requirements is to ensure resilience of an institution to unexpected adverse circumstances, before appropriate mitigating actions and strategy adjustments can be implemented. Therefore, environmental factors that can affect institutions in the short to medium term are expected to be reflected in the prudential framework. However, for those with an impact in the longer term, institutions are expected to take appropriate mitigating actions in their strategy.

- The high confidence level used in the Pillar 1 framework to protect institutions from risks over the short to medium horizon may no longer be achievable and appropriate if longer horizons would be considered.

- To the extent that institutions are exposed to E&S risks in relation to their specific strategy and business model, coverage of these risks in the Pillar 2 own-fund requirements instead of Pillar 1 could be appropriate. In addition, reflection of these risks in the Pillar 2 guidance for stress testing may be considered.

With respect to the internal-ratings-based (IRB) approach for credit risk:

- The Probability of Default (PD) represents a one-year default probability, which is required to be calibrated based on long-run average (‘through-the-cycle’) default rates. As such, longer-term risk characteristics of the obligor may be taken into account.

- The Credit Conversion Factor (CCF) as an estimate of potential additional drawdowns before default naturally relates to the one-year time horizon for the PD, but is expected to reflect the situation of an economic downturn.

- The time horizon for the Loss Given Default (LGD) extends to the full maturity of the exposure and/or the collection process and its calibration is also expected to reflect the situation of an economic downturn.

In the following sections we summarize the EBA recommendations by risk type.

Credit risk

The recommendations of the EBA largely put the burden on financial institutions to take E&S risks into account in the inputs for the existing Pillar 1 framework and/or to apply conservatism or overrides to the outputs. It does not recommend to include explicit E&S risk-related elements in the determination of risk weights for rated and unrated exposures in the SA or in the risk-weight formulas of the IRB. The main reasons for not doing so are that it is not clear what common and objective E&S-related factors should be used as input, what the proper functional form would be, a lack of evidence on which the size of an adjustment could be based so that it results in proper risk differentiation, and the risk of double counting with the reflection of E&S risks in the inputs to the existing own funds calculations under Pillar 1 (external ratings in the SA and PD, LGD and CCF in the case of IRB). However, the EBA will continue to evaluate this possibility in the medium to long term. The EBA also does not recommend introducing an environment-related adjustment factor to the risk weights resulting from the existing Pillar 1 framework[6].

Recommended actions for credit risk

| Short term |

- SA) The EBA encourages rating agencies to integrate environmental and social factors as drivers in the external credit risk assessments and to provide enhanced disclosures and transparency about the rating methodologies.

- (SA) Financial institutions to explicitly consider environmental factors in the due diligence that they are required to perform when using external credit risk assessments.

- (IRB) Financial institutions to reflect E&S risks in the rating assignment, risk quantification (for example through a margin of conservatism or the downturn component) and/or expert judgment and overrides, without affecting the overall performance of the rating system. In this context:

- Quantification of risks must be based on sufficient and reliable observations;

- Overrides should be for specific, individual cases where the institution believes there is material exposure to E&S risks but it has insufficient information to quantify it. Such overrides need to be regularly assessed and challenged;

- If an institution derives PDs for internal rating grades by a mapping to a scale from a credit rating institution, it needs to consider whether the default rates associated with the external scale reflect material E&S risks.

- To assess E&S risks at a borrower level, institutions need to have a process to obtain and update material E&S-related information on the borrowers’ financial condition and on credit facility characteristics, as part of the due diligence during onboarding and ongoing monitoring of borrowers’ risk profile.

- (IRB) Financial institutions to consider E&S risks in their stress testing programs.

- (SA, IRB) Financial institutions to ensure prudent valuation of immovable property collateral, considering climate-related physical and transition risks as well as other environmental risks. The prudent valuation should be considered at origination, re-valuation and during monitoring.

| Medium to long term |

- (SA) Financial institutions to monitor that environmental factors are reflected in financial collateral valuations through market values under Pillar 1 and valuation methodologies under Pillar 2.

- (SA) The EBA to consider whether benefits from the Infrastructure Supporting Factor (ISF) should only be applied to high-quality specialized lending corporate exposures that meet strong environmental standards.

- (SA) The EBA to consider adjusting risk weights, both in general and specifically for those assigned to real estate exposures.

- (IRB) As E&S risks materialize in defaults and loss rates over time, institutions need to redevelop or recalibrate their PD and LGD estimates.

(SA = standardized approach; IRB = Internal-rating-based approach)

Market risk

Within market risk, the EBA sees the main interaction of E&S risks with the equity, credit spread and commodity markets, in which E&S risks may cause additional volatility. In line with the existing regulatory guidance, the EBA expects E&S risks not to be treated as separate risk factors but as drivers of existing risk factors, with the exception of products for which cash flows depend specifically on ESG factors (‘ESG-linked products’).

The EBA does not recommend changes at this point to the standardized approach (SA) and the internal model approach (IMA) under the FRTB regulation, which will come into effect in the EU in 2025. The primary reason is the lack of sufficient evidence on the impact of E&S risks to enable a data driven approach, which forms the basis of the FRTB.

When calculating the expected shortfall (ES) measure under the IMA based on last 12 months' market data, the materialization of E&S risks will automatically be reflected in the market data that is used. When using market data from a stress period, either to calculate ES in the IMA or to calibrate risk factor shocks for the sensitivity-based measure (SbM) at a risk class level in the SA, the reflection of E&S risks will depend on the choice of stress period. To include E&S risks fully in the IMA but avoid overlap with the (partial) presence of E&S risks in historical data, the EBA views the consideration of E&S risks in a separate ‘risk not in the model engine’ (RNIME) add-on as most promising option for the medium to long term, leveraging the framework described in the ECB Guide to internal models[7].

Recommended actions for market risk

| Short term |

- (SA, IMA) Financial institutions to consider environmental risks in relation to their trading book risk appetite, internal trading limits and new product approval.

- (IMA) Financial institutions to consider environmental risk as part of their stress testing program that is required to get internal model approval.

| Medium to long term |

- (SA, IMA) Competent authorities to consider how to treat ESG-linked products for the residual risk add-on in the SA and in the IMA.(SA) The EBA to consider including a dimension for ESG risks in the existing equity and credit spread risk classes, or including a separate environmental risk class.

- (IMA) Financial institutions to consider ESG risks when monitoring risks that are not included in the model, for which the ECB’s RNIME framework could be used as a basis.

(SA = standardized approach; IRB = Internal-rating-based approach)

Operational risk

The EBA notes that various types of operational risks can increase as a result of E&S risks, including damage to physical assets, disruption of business processes and litigation. However, the new standardized approach (SA) for operational risk in the Basel III framework, which will come into effect in the EU in 2025, does not have a forward-looking component – it only considers historical loss experience (besides business indicators). Historical losses are unlikely to fully reflect the potential future impact of E&S risks, but there is as of yet insufficient evidence and data to quantify and consider this in an amendment of the SA.

Recommended actions for operational risk

| Short term |

- Financial institutions to identify whether E&S risks constitute triggers of operational risk losses.

| Medium to long term |

- Following evidence of E&S risk factors to trigger operational risk losses, the EBA to consider whether revisions to the BCBS SA methodology are warranted.

Liquidity risk

The EBA report describes three ways in which E&S risks may affect the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) calculation. First, liquid assets that are specifically exposed to E&S risks may become less liquid and/or decrease in value. As a consequence, they may no longer satisfy the eligibility criteria for liquid assets. If they still do, then the decrease in market value would reflect the lower liquidity and reduce the LCR. Second, contingent liabilities arising from environmentally harmful investments would need to be included as outflows in the LCR calculation, thereby lowering the LCR. Third, a decrease in credit quality of receivables that are particularly exposed to E&S risks will decrease the inflows that can be taken into account in the LCR calculation. The EBA concludes that the existing LCR framework can capture the impact of E&S risks on the definition of liquid assets, outflows and inflows, so that no amendments are needed.

Regarding the existing framework for the net stable funding ratio (NSFR), the EBA notes that a reduction in the creditworthiness and/or liquidity of loans and securities exposed to E&S risks would lead to a higher requirement for stable funding and thereby negatively impact the NSFR. In this way, the existing NSFR framework can capture the impact of E&S risks on the definition of stable assets.

In summary, the EBA does not propose changes to the LCR and NSFR frameworks in relation to E&S risks. In case of excessive exposure to E&S risks for individual institutions, it notes that supervisors can set specific liquidity or funding requirements as part of the Pillar 2 framework for LCR and NSFR.

Concentration risk

The SA and IRB of the Pillar 1 framework for credit risk assume that a bank’s loan portfolio has full diversification of name-specific (idiosyncratic) risk and is well diversified across sectors and geographies. Because of these assumptions, the framework is not able to capture concentration risks, including those arising from E&S risks. In the current framework, single-name concentration risk is separately captured in Pillar 1 using the large exposure regime. Sector and geographic concentrations are considered in the SREP process under Pillar 2.

Recommended actions for concentration risk

| Short term |

- The EBA to develop a definition of environment-related concentration risk as well as exposure-based metrics for its quantification (e.g., ratio of exposures sensitive to a given environmental risk driver in a specific geographical area or in a specific industry sector over total exposures, total capital or RWA). These metrics will be part of supervisory reporting and, when relevant, external disclosure. In addition, they should be considered as part of Pillar 2 under SREP and/or supplement Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks.The EBA does not recommend to change the existing large exposure regime.

| Medium to long term |

- Based on the experience obtained with initial environment-related concentration risk metrics and quantification, the EBA may consider enhanced metrics and the appropriateness to introduce it in the Pillar 1 framework.

- This would entail the design and calibration of possible limits and thresholds, add-ons or buffers, as well as the specification of possible consequences if there are breaches.

Capital buffers and macroprudential framework

An alternative to amending the calculation of capital requirements to capture E&S risks in the prudential framework would be to increase the minimum required level of capital and/or to implement ‘borrower-based measures’ (BMM). Such BMMs aim to prevent a build-up of risk concentrations, for example by setting upper bounds on loan-to-value or loan-to-income for mortgage lending. Of the various possibilities, the EBA deems the use of a systemic risk capital buffer as the most suitable, although a double counting with the inclusion of E&S risks in the calculation of capital requirements under Pillar 1 and 2 needs to be avoided.

Recommended actions for capital buffers and macroprudential framework

| Short term |

- The EBA to asses changes to the guidelines on the appropriate subsets of sectoral exposures to which a systematic risk buffer may be applied.

| Medium to long term |

- The EBA to coordinate with other ongoing initiatives and assess the most appropriate adjustments.

Conclusion

The EBA considers E&S risks as a new source of systemic risk, which may not be adequately captured in the existing prudential framework. At the same time, the EBA recognizes the challenges in assessing the impact of these risks on regulatory metrics. The challenges range from a lack of granular and comparable data, varying definitions of what is environmentally and socially sustainable, historic data not being representative of what can be expected in the future, to the high uncertainty about the probability of future materialization of E&S risks. Moreover, the time horizon considered in the existing Pillar 1 framework is much shorter than the long horizon over which environmental risks are likely to fully materialize, with an exception of short-term acute physical and transition risks.

Against this background, the EBA does not recommend concrete quantitative adjustments to the existing Pillar 1 framework at this point. Nonetheless, it does expect financial institutions to take E&S risks into account in the inputs to the existing Pillar 1 framework or to apply overrides based on expert judgment. The EBA further proposes actions that should provide more clarity over time about the drivers and materiality of E&S risks. In due time, this can provide the basis for quantitative amendments to the Pillar 1 framework.

If you are interested to discuss this topic in more detail or would like support to embed E&S risks in your organization, please contact Pieter Klaassen at p.klaassen@zandersgroup.com or +41 78 652 5505.

[1]EBA (2023), Report on the role of environmental and social risks in the prudential framework (link), October.

[2] EBA (2022), Discussion paper on the role of environmental risks in the prudential framework (link), May. For a summary, see the article (link) on the Zanders website.

[3] ECB (2020), Guide on climate-related and environmental risks (link), November.

[4] See section 2.3.2 in EBA (2021), Report on management and supervision of ESG risks for credit institutions and investment firms (link), June.

[5] ECB (2020), Guide on climate-related and environmental risks (link), November.

[6] In the current EU Pillar 1 framework, adjustments are included that result in lower risk weights for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME) and infrastructure lending. As the EBA notes, these adjustments are not risk-based but have been included in the EU to support lending to SMEs and for infrastructure projects.

New Examination Priorities for Supervisors: Improving supervisory practices across the EU

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

Liquidity and funding risk

While European banks generally have sufficient liquidity, there are potential challenges on the horizon. Recent events, including bank failures in the United States and the issues with Credit Suisse, have underscored the importance for banks to have a framework in place that allows a quick response to market volatility and changes in liquidity.

Several factors contribute to these challenges, such as the end of funding programs (i.e. quantitative easing and the TLTRO program), changes in market interest rates, and evolving depositor behavior. The EBA stresses it's not just about meeting regulatory requirements; banks are urged to manage liquidity proactively, maintain reasonable liquidity buffers beyond regulatory mandates, diversify their funding sources, and adapt to changing market dynamics.

The EBA also stresses that the role of social media in relation to the financial markets cannot be underestimated. Banks are encouraged to incorporate social media sentiment into their stress-testing frameworks and develop strategies to counter the impact of negative social media news on deposit withdrawals or market funding stability.

Supervisory authorities should assess institutions’ liquidity risk, funding profiles, and their readiness to deal with wholesale/retail counterparties and funding concentrations. They should also scrutinize banks’ internal liquidity adequacy assessment processes (ILAAP) and their ability to sell securities under different market conditions. Relevant to the increased scrutiny of liquidity and funding risk are the revised technical standards on supervisory reporting on liquidity, published in the summer of 2023 (EBA, June 2023).

Interest rate risk and hedging

The transition from an era of persistently low or even negative interest rates to a period of rising rates and persistent inflation is a major concern for banks in 2024. While the initial impact on net interest margins may be positive, banks face challenges in managing interest rate risk effectively.

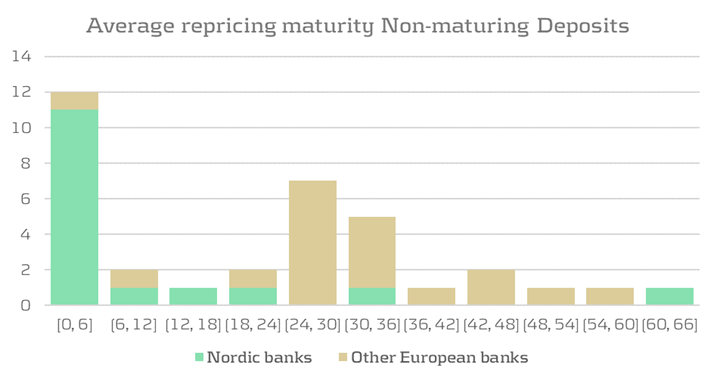

Supervisors are tasked with assessing whether banks have suitable organizational frameworks for managing interest rate risk. This includes examining responsibilities at the management level and ensuring that senior management is implementing effective interest rate risk strategies. Moreover, supervisors should evaluate how changes in interest rates may impact an institution’s Net Interest Income (NII) and Economic Value of Equity (EVE). This involves examining assumptions about customers’ behavior, particularly in the context of deposit funding in the digital age.

Interest rate risk and liquidity and funding risk are closely linked, and supervisors are encouraged to consider these links in their assessments, reflecting the interconnected nature of these topics. The new guidelines on IRRBB and CSRBB (EBA, July 2023) emphasize this interconnectedness. It underscores the necessity for financial institutions and regulatory bodies alike to adopt a holistic approach, recognizing that addressing one risk may have cascading effects on others.

The EBA has announced a data collection scheme regarding IRRBB data of financial institutions, highlighting the priority the EBA gives to IRRBB. The data collection exercise is based on the newly published implementing technical standards (ITS) for IRRBB and has a March 2023 deadline. The collection of the IRRBB data will only apply to those institutions that are already reporting IRRBB to the EBA in the context of the QIS exercise.

Recovery operationalization

Recent financial market events (such as Credit Suisse, SVB) have underscored the importance of being prepared for swift and effective crisis responses. Recovery plans, which banks are required to have in place, must be updated and they must include credible options to restore financial soundness in a timely manner.

Supervisors play a vital role in assessing the adequacy and severity of scenarios in recovery plans. These scenarios must be sufficiently severe to trigger the full range of available recovery options, allowing institutions to demonstrate their capacity to restore business and financial viability in a crisis.

Moreover, the Overall Recovery Capacity (ORC) is a key outcome of recovery planning, providing an indication of the institution’s ability to restore its financial position following a significant downturn. It’s crucial for supervisors to review the adequacy and quality of the ORC, with a focus on liquidity recovery capacity.

To ensure the effectiveness of recovery plans, supervisors should also encourage banks to perform dry-run exercises and assess the suitability of communication arrangements, including faster communication tools like social media.

A strategic imperative

Beyond these key focus areas, the EBA also emphasizes the ongoing relevance of issues such as asset quality, cyber risk, and data security. These challenges remain important in the supervisory landscape, although they are not the main priorities in the coming year.

Thus, in light of the EBA’s aforementioned regulatory priorities for 2024, it is imperative for all financial institutions across the European Union to proactively engage in ensuring the stability and resilience of the banking sector. From a liquidity perspective, it is vital to actively manage your financial institution’s liquidity and anticipate the ripples of market volatility. Moreover, the insights of social media sentiment within your stress-testing frameworks can add vital information. The ability to navigate funding challenges is not just a regulatory requirement; it’s a strategic imperative.

The shift to the current high interest rate environment warrants an assessment of a bank’s organizational readiness for this change. Make sure that your senior management is not only aware of implementing effective interest rate risk strategies but also adept at them. Moreover, scrutinize the impact of changing interest rates on your NII and EVE.

How can Zanders support?

Zanders is a thought leader in the management and modeling of IRRBB. We enable financial institutions to meet their strategic risk goals while achieving regulatory compliance, by offering support from strategy to implementation. In light of the aforementioned regulatory priorities of the EBA, we can support and guide you through these changes in the world of IRRBB with agility and foresight.

Are you interested in IRRBB-related topics? Contact Jaap Karelse, Erik Vijlbrief (Netherlands, Belgium and Nordic countries) or Martijn Wycisk (DACH region) for more information.

EBA, July 2023. Guidelines on IRRBB and CSRBB. s.l.:s.n.

EBA, June 2023. Implementing Technical Standards on supervisory reporting amendments with regards to COREP, asset encumbrance and G-SIIs. s.l.:s.n.

EBA, September 2023. Work Program 2024. s.l.:s.n.

ECB – Cyber Resilience Stress Test: Scope, Methodology and Scenario.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

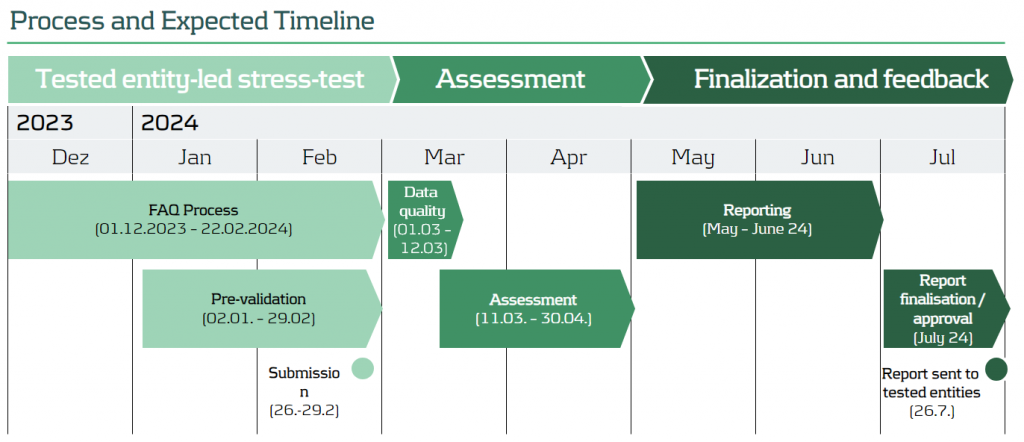

In the stress test methodology, participating banks are required to evaluate the impact of a cyber attack. They must communicate their response and recovery efforts by completing a questionnaire and submitting pertinent documentation. Banks undergoing enhanced assessment are further mandated to conduct and report the results of IT recovery tests specific to the scenario. The reporting of the cyber incident is to be done using the template outlined in the SSM Cyber-incident reporting framework.

Assessing Digital Fortitude: Scope and Objectives

The ECB's decision to conduct a thematic stress test on cyber resilience in 2024 holds profound significance. The primary objective is to assess the digital operational resilience of 109 Significant Institutions, contemplating the impact of a severe but plausible cybersecurity event. This initiative seeks to uncover potential weaknesses within the systems and derive strategic remediation actions. Notably, 28 banks will undergo an enhanced assessment, heightening the scrutiny on their cyber resilience capabilities. The outcomes are poised to reverberate across the financial landscape, influencing the 2024 SREP OpRisk Score and shaping qualitative requirements.

General Overview and Scope

- Supervisory Board of ECB has decided to conduct a thematic stress test on „cyber resilience“ in 2024.

- Main objective is to assess the digital operational resilience in case of a severe but plausible cybersecurity event, to identify potential weaknesses and derive remediation actions.

- Participants will be 109 Significant Institutions (28 banks will be in scope of an enhanced assessment).

- The outcome will have an impact on the 2024 SREP OpRisk Score and qualitative requirements.

Navigating the Evaluation: Stress Test Methodology

Participating banks find themselves at the epicenter of this evaluative process. They are tasked with assessing the impact of a simulated cyber attack and meticulously reporting their response and recovery efforts. This involves answering a comprehensive questionnaire and providing relevant documentation as evidence. For those under enhanced assessment, an additional layer of complexity is introduced – the execution and reporting of IT recovery tests tailored to the specific scenario. The cyber incident reporting follows a structured template outlined in the SSM Cyber-incident reporting framework.

Stress Test Methodology

- Participating banks have to assess the impact of the cyber-attack and report their response and recovery by answering the questionnaire and providing relevant documentation as evidence.

- Banks under the enhanced assessment are additionally requested to execute and provide results of IT recovery tests tailored to the specific scenario.

- The cyber incident has to be reported by using the template of the SSM Cyber-incident reporting framework.

Setting the Stage: Scenario Unveiled

The stress test unfolds with a meticulously crafted hypothetical scenario. Envision a landscape where all preventive measures against a cyber attack have either been bypassed or failed. The core of this simulation involves a cyber-attack causing a loss of integrity in the databases supporting a bank's main core banking system. Validation of the affected core banking system is a crucial step, overseen by the Joint Supervisory Team (JST). The final scenario details will be communicated on January 2, 2024, adding a real-time element to this strategic evaluation.

Scenario

- The stress test will consist of a hypothetical scenario that assumes that all preventive measures have been bypassed or have failed.

- The cyber-attack will cause a loss of integrity of the database(s) that support the bank’s main core banking system.

- The banks have to validate the selection of the affected core banking system with the JST.

- The final scenario will be communicated on 2 January 2024.

Partnering for Success: Zanders' Service Offering

In the complex terrain of the Cyber Resilience Stress Test, Zanders stands as a reliable partner. Armed with deep knowledge in Non-Financial Risk, we navigate the intricacies of the upcoming stress test seamlessly. Our support spans the entire exercise, from administrative aspects to performing assessments that determine the impact of the cyber attack on key financial ratios as requested by supervisory authorities. This service offering underscores our commitment to fortifying financial institutions against evolving cyber threats.

Zanders Service Offering

- Our deep knowledge in Non-Financial Risk enables us to navigate smoothly through the complexity of the upcoming Cyber Resilience Stress Test.

- We support participating banks during the whole exercise of the upcoming Stress Test.

- Our Services cover the whole bandwidth of required activities starting from administrative aspects and ending up at performing assessments to determine the impact of the cyber-attack in regard of key financial ratios requested by the supervisory authority.

Biodiversity risks and opportunities for financial institutions explained

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

In this report, biodiversity loss ranks as the fourth most pressing concern after climate change adaptation, mitigation failure, and natural disasters. For financial institutions (FIs), it is therefore a relevant risk that should be taken into account. So, how should FIs implement biodiversity risk in their risk management framework?

Despite an increasing awareness of the importance of biodiversity, human activities continue to significantly alter the ecosystems we depend on. The present rate of species going extinct is 10 to 100 times higher than the average observed over the past 10 million years, according to Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials[i]. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) reports that 75% of ecosystems have been modified by human actions, with 20% of terrestrial biomass lost, 25% under threat, and a projection of 1 million species facing extinction unless immediate action is taken. Resilience theory and planetary boundaries state that once a certain critical threshold is surpassed, the rate of change enters an exponential trajectory, leading to irreversible changes, and, as noted in a report by the Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), we are already close to that threshold[ii].

We will now explain biodiversity as a concept, why it is a significant risk for financial institutions (FIs), and how to start thinking about implementing biodiversity risk in a financial institutions’ risk management framework.

What is biodiversity?

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) defines biodiversity as “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, i.a., terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part.”[iii] Humans rely on ecosystems directly and indirectly as they provide us with resources, protection and services such as cleaning our air and water.

Biodiversity both affects and is affected by climate change. For example, ecosystems such as tropical forests and peatlands consist of a diverse wildlife and act as carbon sinks that reduce the pace of climate change. At the same time, ecosystems are threatened by the accelerating change caused by human-induced global warming. The IPBES and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in their first-ever collaboration, state that “biodiversity loss and climate change are both driven by human economic activities and mutually reinforce each other. Neither will be successfully resolved unless both are tackled together.”[iv]

Why is it relevant for financial institutions?

While financial institutions’ own operations do not materially impact biodiversity, they do have impact on biodiversity through their financing. ASN Bank, for instance, calculated that the net biodiversity impact of its financed exposure is equivalent to around 516 square kilometres of lost biodiversity – which is roughly equal to the size of the isle of Ibiza in Spain[v]. The FIs’ impact on biodiversity also leads to opportunities. The Institute Financing Nature (IFN) report estimates that the financing gap for biodiversity is close to $700 billion annually[vi]. This emphasizes the importance of directing substantial financial resources towards biodiversity-positive initiatives.

At the same time, biodiversity loss also poses risks to financial institutions.

The global economy highly depends on biodiversity as a result of the increasedglobalization and interconnectedness of the financial system. Due to these factors, the effects of biodiversity losses are magnified and exacerbated through the financial system, which can result in significant financial losses. For example, approximately USD 44 trillion of the global GDP is highly or moderately dependent on nature (World Economic Forum, 2020). Specifically for financial institutions, the DNB estimated that Dutch FIs alone have EUR 510 billionof exposure to companies that are highly or very highly dependent on one or more ecosystems services[vii]. Furthermore, in the 2010 World Economic Forum report worldwide economic damage from biodiversity loss is estimated to be around USD 2 to 4.5 trillion annually. This is remarkably high when compared to the negative global financial damage of USD 1.7 trillion per year from greenhouse gas emissions (based on 2008 data), which demonstrates that institutions should not focus their attention solely on the effects of climate change when assessing climate & environmental risks[viii].

Examples of financial impact

Similarly to climate risk, biodiversity risk is expected to materialize through the traditional risk types a financial institution faces. To illustrate how biodiversity loss can affect individual financial institutions, we provide an example of the potential impact of physical biodiversity risk on, respectively, the credit risk and market risk of an institution:

Credit risk:

Failing ecosystem services can lead to disruptions of production, reducing the profits of counterparties. As a result, there is an increase in credit risk of these counterparties. For example, these disruptions can materialize in the following ways:

- A total of 75% of the global food crop rely on animals for their pollination. For the agricultural sector, deterioration or loss of pollinating species may result in significant crop yield reduction.

- Marine ecosystems are a natural defence against natural hazards. Wetlands prevented USD 650 million worth of damages during the 2012 Superstorm Sandy [OECD, 2019), while the material damage of hurricane Katrina would have been USD 150 billion less if the wetlands had not been lost.

Market risk:

The market value of investments of a financial institution can suffer from the interconnectedness of the global economy and concentration of production when a climate event happens. For example:

- A 2011 flood in Thailand impacted an area where most of the world's hard drives are manufactured. This led to a 20%-40% rise in global prices of the product[ix]. The impact of the local ecosystems for these type of products expose the dependency for investors as well as society as a whole.

Core part of the European Green Deal

The examples above are physical biodiversity risk examples. In addition to physical risk, biodiversity loss can also lead to transition risk – changes in the regulatory environment could imply less viable business models and an increase in costs, which will potentially affect the profitability and risk profile of financial institutions. While physical risk can be argued to materialize in a more distant future, transition risk is a more pressing concern as new measures have been released, for example by the European Commission, to transition to more sustainable and biodiversity friendly practices. These measures are included in the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030 and the EU’s Nature restoration law.

The EU’s biodiversity strategy for 2030 is a core part of European Green Deal. It is a comprehensive, ambitious, and long-term plan that focuses on protecting valuable or vulnerable ecosystems, restoring damaged ecosystems, financing transformation projects, and introducing accountability for nature-damaging activities. The strategy aims to put Europe's biodiversity on a path to recovery by 2030, and contains specific actions and commitments. The EU biodiversity strategy covers various aspects such as:

- Legal protection of an additional 4% of land area (up to a total of 7%) and 19% of sea area (up to a total of 30%)

- Strict protection of 9% of sea and 7% of land area (up to a total of 10% for both)

- Reduction of fertilizer use by at least 20%

- Setting measures for sustainable harvesting of marine resources

A major step forwards towards enforcement of the strategy is the approval of the Nature restoration law by the EU in July 2023, which will become the first continent-wide comprehensive law on biodiversity and ecosystems. The law is likely to impact the agricultural sector, as the bill allows for 30% of all former peatlands that are currently exploited for agriculture to be restored or partially shifted to other uses by 2030. By 2050, this should be at least 70%. These regulatory actions are expected to have a positive impact on biodiversity in the EU. However, a swift implementation may increase transition risk for companies that are affected by the regulation.

The ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks explicitly states that biodiversity loss is one of the risk drivers for financial institutions[x]. Furthermore, the ECB Guide requires financial institutions to asses both physical and transition risks stemming from biodiversity loss. In addition, the EBA Report on the Management and Supervision of ESG Risk for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms repeatedly refers to biodiversity when discussing physical and transition risks[xi].

Moreover, the topic ‘biodiversity and ecosystems’ is also covered by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which requires companies within its scope to disclose on several sustainability related matters using a double materiality perspective.[1] Biodiversity and ecosystems is one of five environmental sustainability matters covered by CSRD. At a minimum, financial institutions in scope of CSRD must perform a materiality assessment of impacts, risks and opportunities stemming from biodiversity and ecosystems. Furthermore, when biodiversity is assessed to be material, either from financial or impact materiality perspective, the institution is subject to granular biodiversity-related disclosure requirements covering, among others, topics such as business strategy, policies, actions, targets, and metrics.

Where to start?

In line with regulatory requirements, financial institutions should already be integrating biodiversity into their risk management practices. Zanders recognizes the challenges associated with biodiversity-related risk management, such as data availability and multidimensionality. Therefore, Zanders suggests to initiate this process by starting with the following two steps. The complexity of the methodologies can increase over time as the institution’s, the regulator’s and the market’s knowledge on biodiversity-related risks becomes more mature.

- Perform materiality assessment using the double materiality concept. This means that financial institutions should measure and analyze biodiversity-related financial materiality through the identification of risks and opportunities. Institutions should also assess their impacts on biodiversity, for example, through calculation of their biodiversity footprint. This can start with classifying exposures’ impact and dependency on biodiversity based on a sector-level analysis.

- Integrate biodiversity-related risks considerations into their business strategy and risk management frameworks. From a business perspective, if material, financial institutions are expected to integrate biodiversity in their business strategy, and set policies and targets to manage the risks. Such actions could be engagement with clients to promote their sustainability practices, allocation of financing to ‘biodiversity-friendly’ projects, and/or development of biodiversity specific products. Moreover, institutions are expected to adjust their risk appetites to account for biodiversity-related risks and opportunities, establish KRIs along with limits and thresholds. Embedding material ESG risks in the risk appetite frameworks should include a description on how risk indicators and limits are allocated within the banking group, business lines and branches.

Considering the potential impact of biodiversity loss on financial institutions, it is crucial for them to extend their focus beyond climate change and also start assessing and managing biodiversity risks. Zanders can support financial institutions in measuring biodiversity-related risks and taking first steps in integrating these risks into risk frameworks. Curious to hear more on this? Please reach out to Marije Wiersma, Iryna Fedenko, or Jaap Gerrits.

[1] CSRD applies to large EU companies, including banks and insurance firms. The first companies subject to CSRD must disclose according to the requirements in the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) from 2025 (over financial year 2024), and by the reporting year 2029, the majority of European companies will be subject to publishing the CSRD reports. The sustainability report should be a publicly available statement with information on the sustainability-matters that the company considers material. This statement needs to be audited with limited assurance.

[i] PBAF. (2023). Dependencies - Pertnership for Biodiversity Acccounting Financials (PBAF)

[ii] De Nederlandche Bank. (2020). Indepted to nature - Exploring biodiversity risks for the Dutch Financial Sector.

[iii] CBD. (2005). Handbook of the convention on biological diversity

[iv] IPBES. (2021). Tackling Biodiversity & Climate Crises Together & Their Combined Social Impacts

[v] ASN Bank (2022). ASN Bank Biodiversity Footprint

[vi] Paulson Institute. (2021). Financing nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity

[vii] De Nederlandche Bank. (2020). Indepted to nature - Exploring biodiversity risks for the Dutch Financial Sector

[viii] PwC for World Economic Forum. (2010). Biodiversity and business risk

[ix] All the examples related to credit and market risk are presented in the report by De Nederlandsche Bank. (2020). Biodiversity Opportunities and Risks for the Financial Sector

[x] ECB. (2020). Guide on climate-related and environmental risks.

[xi] EBA. (2021). EBA Report on Management and Supervision of ESG Risk for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms

Blockchain-based Tokenization for decentralized Issuance and Exchange of Carbon Offsets

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

Carbon offset processes are currently dominated by private actors providing legitimacy for the market. The two largest of these, Verra and Gold Standard, provide auditing services, carbon registries and a marketplace to sell carbon offsets, making them ubiquitous in the whole process. Due to this opacity and centralisation, the business models of the existing companies was criticised regarding its validity and the actual benefit for climate action. By buying an offset in the traditional manner, the buyer must place trust in these players and their business models. Alternative solutions that would enhance the transparency of the process as well as provide decentralised marketplaces are thus called for.

The conventional process

Carbon offsets are certificates or credits that represent a reduction or removal of greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere. Offset markets work by having companies and organizations voluntarily pay for carbon offsetting projects. Reasons for partaking in voluntary carbon markets vary from increased awareness of corporate responsibility to a belief that emissions legislation is inevitable, and it is thus better to partake earlier.

Some industries also suffer prohibitively expensive barriers for lowering their emissions, or simply can’t reduce them because of the nature of their business. These industries can instead benefit from carbon offsets, as they manage to lower overall carbon emissions while still staying in business. Environmental organisations run climate-friendly projects and offer certificate-based investments for companies or individuals who therefore can reduce their own carbon footprint. By purchasing such certificates, they invest in these projects and their actual or future reduction of emissions. However, on a global scale, it is not enough to simply lower our carbon footprint to negate the effects of climate change. Emissions would in practice have to be negative, so that even a target of 1,5-degree Celsius warming could be met. This is also remedied by carbon credits, as they offer us a chance of removing carbon from the atmosphere. In the current process, companies looking to take part in the offsetting market will at some point run into the aforementioned behemoths and therefore an opaque form of purchasing carbon offsets.

The blockchain approach

A blockchain is a secure and decentralised database or ledger which is shared among the nodes of a computer network. Therefore, this technology can offer a valid contribution addressing the opacity and centralisation of the traditional procedure. The intention of the first blockchain approaches were the distribution of digital information in a shared ledger that is agreed on jointly and updated in a transparent manner. The information is recorded in blocks and added to the chain irreversibly, thus preventing the alteration, deletion and irregular inclusion of data.

In the recent years, tokenization of (physical) assets and the creation of a digital version that is stored on the blockchain gained more interest. By utilizing blockchain technology, asset ownership can be tokenized, which enables fractional ownership, reduces intermediaries, and provides a secure and transparent ledger. This not only increases liquidity but also expands access to previously illiquid assets (like carbon offsets). The blockchain ledger allows for real-time settlement of transactions, increasing efficiency and reducing the risk of fraud. Additionally, tokens can be programmed to include certain rules and restrictions, such as limiting the number of tokens that can be issued or specifying how they can be traded, which can provide greater transparency and control over the asset.

Blockchain-based carbon offset process

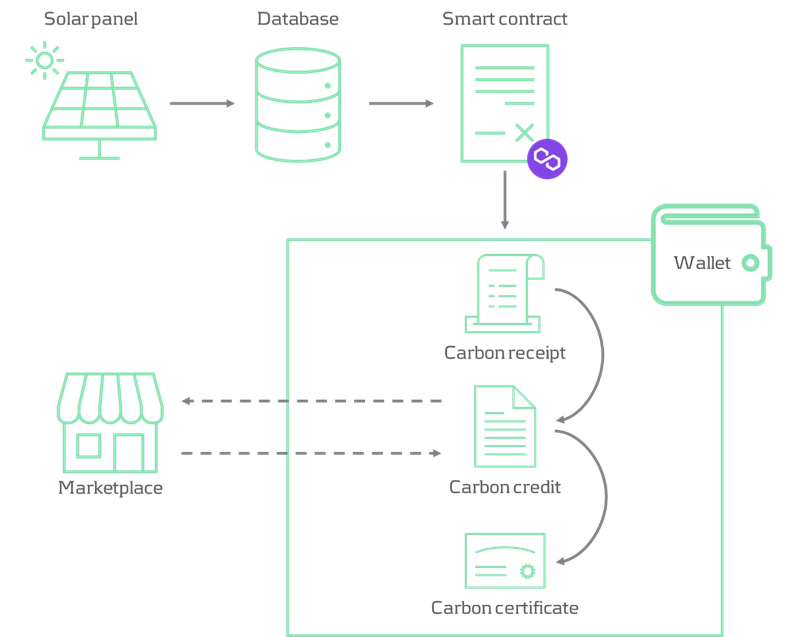

The tokenisation process for carbon credits begins with the identification of a project that either captures or helps to avoid carbon creation. In this example, the focus is on carbon avoidance through solar panels. The generation of solar electricity is considered an offset, as alternative energy use would emit carbon dioxide, whereas solar power does not.

The solar panels provide information regarding their electricity generation, from which a figure is derived that represents the amount of carbon avoided and fed into a smart contract. A smart contract is a self-executing application that exist on the blockchain and performs actions based on its underlying code. In the blockchain-based carbon offset process, smart contracts convert the different tokens and send them to the owner’s wallet. The tokens used within the process are compliant with the ERC-721 Non-Fungible Token (NFT) standard, which represents a unique token that is distinguishable from others and cannot be exchanged for other units of the same asset. A practical example is a work of art that, even if replicated, is always slightly different.

In the first stage of the process, the owner claims a carbon receipt, based on the amount of carbon avoided by the solar panel. Thereby the aggregated amount of carbon avoided (also stored in a database just for replication purposes) is sent to the smart contract, which issues a carbon receipt of the corresponding figure to the owner. Carbon receipts can further be exchanged for a uniform amount of carbon credits (e.g. 5 kg, 10 kg, 15 kg) by interacting with the second smart contract. Carbon credits are designed to be traded on the decentralised marketplace, where the price is determined by the supply and demand of its participants. Ultimately, carbon credits can be exchanged for carbon certificates indicating the certificate owner and the amount of carbon offset. Comparable with a university diploma, carbon certificates are tied to the address of the owner that initiated the exchange and are therefore non-tradable. Figure 1 illustrates the process of the described blockchain-based carbon offset solution:

Figure 1: Process flow of a blockchain-based carbon offset solution

Conclusion

The outlined blockchain-based carbon offset process was developed by Zanders’ blockchain team in a proof of concept. It was designed as an approach to reduce dependence on central players and a transparent method of issuing carbon credits. The smart contracts that the platform interacts with are implemented on the Mumbai test network of the public Polygon blockchain, which allows for fast transaction processing and minimal fees. The PoC is up and running, tokenizing the carbon savings generated by one of our colleagues photovoltaic system, and can be showcased in a demo. However, there are some clear optimisations to the process that should be considered for a larger scale (commercial) setup.

If you're interested in exploring the concept and benefits of a blockchain-based carbon offset process involving decentralised issuance and exchange of digital assets, or if you would like to see a demo, you can contact Robert Richter or Justus Schleicher.

The 2023 Banking Turmoil

The European Banking Authority (EBA) published its roadmap on the Banking Package, which implements the final Basel III reforms in the European Union.

Early October, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) published a report[1] on the 2023 banking turmoil that involved the failure of several US banks as well as Credit Suisse. The report draws lessons for banking regulation and supervision which may ultimately lead to changes in banking regulation as well as supervisory practices. In this article we summarize the main findings of the report[2]. Based on the report’s assessment, the most material consequences for banks, in our view, could be in the following areas:

- Reparameterization of the LCR calculation and/or introduction of additional liquidity metrics

- Inclusion of assets accounted for at amortized cost at their fair value in the determination of regulatory capital

- Implementation of extended disclosure requirements for a bank's interest rate exposure and liquidity position

- More intensive supervision of smaller banks, especially those experiencing fast growth and concentration in specific client segments

- Application of the full Basel III Accord and the Basel IRRBB framework to a larger group of banks

Bank failures and underlying causes

The BCBS report first describes in some detail the events that led to the failure of each of the following banks in the spring of 2023:

- Silicon Valley Bank (SVB)

- Signature Bank of New York (SBNY)

- First Republic Bank (FRB)

- Credit Suisse (CS)

While each failure involved various bank-specific factors, the BCBS report highlights common features (with the relevant banks indicated in brackets).

- Long-term unsustainable business models (all), in part due to remuneration incentives for short-term profits

- Governance and risk management did not keep up with fast growth in recent years (SVB, SBNY, FRC)

- Ineffective oversight of risks by the board and management (all)

- Overreliance on uninsured customer deposits, which are more likely to be withdrawn in a stress situation (SVB, SBNY, FRC)

- Unprecedented speed of deposit withdrawals through online banking (all)

- Investment of short-term deposits in long-term assets without adequate interest-rate hedges (SVB, FRC)

- Failure to assess whether designated assets qualified as eligible collateral for borrowing at the central bank (SVB, SBNY)

- Client concentration risk in specific sectors and on both asset and liability side of the balance sheet (SVB, SBNY, FRC)

- Too much leniency by supervisors to address supervisory findings (SVB, SBNY, CS)

- Incomplete implementation of the Basel Framework: SVB, SBNY and FRB were not subject to the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) of the Basel III Accord and the BCBS standard on interest rate risk in the banking book (IRRBB)

Of the four failed banks, only Credit Suisse was subject to the LCR requirements of the Basel III Accord, in relation to which the BCBS report includes the following observations:

- A substantial part of the available high quality liquid assets (HQLA) at CS was needed for purposes other than covering deposit outflows under stress, in contrast to the assumptions made in the LCR calculation

- The bank hesitated to make use of the LCR buffer and to access emergency liquidity so as to avoid negative signalling to the market

Although not part of the BCBS report, these observations could lead to modifications to the LCR regulation in the future.

Lessons for supervision

With respect to supervisory practices, the BCBS report identifies various lessons learned and raises a few questions, divided into four main areas:

1. Bank’s business models

- Importance of forward-looking assessment of a bank’s capital and liquidity adequacy because accounting measures (on which regulatory capital and liquidity measures are based) mostly are not forward-looking in nature

- A focus on a bank’s risk-adjusted profitability

- Proactive engagement with ‘outlier banks’, e.g., banks that experienced fast growth and have concentrated funding sources or exposures

- Consideration of the impact of changes in the external environment, such as market conditions (including interest rates) and regulatory changes (including implementation of Basel III)

2. Bank’s governance and risk management

- Board composition, relevant experience and independent challenge of management

- Independence and empowerment of risk management and internal audit functions

- Establishment of an enterprise-wide risk culture and its embedding in corporate and business processes.

- Senior management remuneration incentives

3.Liquidity supervision

- Do the existing metrics (LCR, NSFR) and supervisory review suffice to identify start of material liquidity outflows?

- Should the monitoring frequency of metrics be increased (e.g., weekly for business as usual and daily or even intra-day in times of stress)?

- Monitoring of concentration risks (clients as well as funding sources)

- Are sources of liquidity transferable within the legal entity structure and freely available in times of stress?

- Testing of contingency funding plans

4. Supervisory judgment

- Supplement rules-based regulation with supervisory judgment in order to intervene pro-actively when identifying risks that could threaten the bank’s safety and soundness. However, the report acknowledges that a supervisor may not be able to enforce (pre-emptive) action as long as an institution satisfies all minimum requirements. This will also depend on local legislative and regulatory frameworks

Lessons for regulation

In addition, the BCBS report identifies various potential enhancement to the design and implementation of bank regulation in four main areas:

1. Liquidity standards

- Consideration of daily operational and intra-day liquidity requirements in the LCR, based on the observation that a material part of the HQLA of CS was used for this purpose but this is not taken into account in the determination of the LCR

- Recalibration of deposit outflows in the calculation of LCR and NSFR, based on the observation that actual outflow rates at the failed banks significantly exceeded assumed outflows in the LCR and NSFR calculations