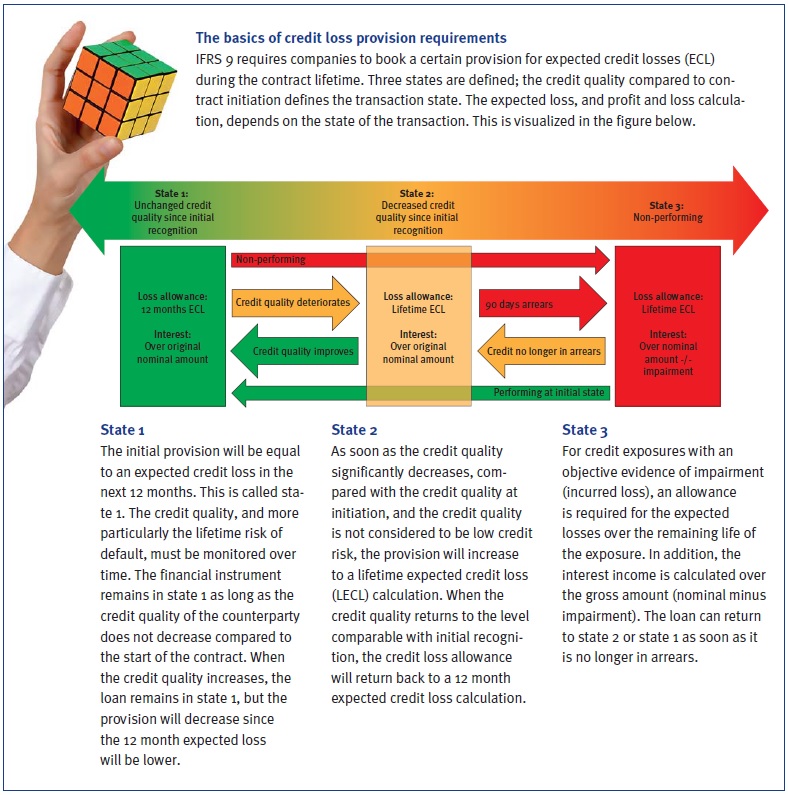

As of January 2018, new accounting rules will come into effect for financial institutions and listed companies with respect to the measurement of impairments. So far, only a few banks act as early adaptors; most choose to be late followers and ‘watch the hare running’. The new rules are principle-based and simple. The design and implementation, however, can be challenging, especially the treatment of forward-looking aspects.

Most banks are struggling to work out how to implement the new impairment rules. Uncertainty over how to deal with current expected credit loss taking into account future macroeconomic scenarios as required by IFRS 9, means credit risk modeling experts, quants and finance experts are in uncharted waters. Different firms have different options on the matter. The primary objective of accounting standards is to provide financial information that stakeholders find useful when making decisions. The new accounting rules regarding provisions will make reserves more timely and sufficient. However, with the new standard, banks are squeezed between P&L volatility, model risk, macroeconomic forecasting and compliance with accounting standards.

Impact

IFRS 9 will, amongst others, rock the balance sheet, affect business models, risk awareness, processes, analytics, data and systems across several dimensions.

We will name a few related to the financials:

- Transition from IAS 39 to IFRS 9 will lead to a change in the level of provision for credit losses. The transition of the current provisions, which are based only on actual losses and incurred but not reported (IBNR) losses, to an expected loss is likely to have significant impact on shareholder equity, net income and capital ratios.

- P&L volatility is expected to increase after transition, since deterioration in credit quality or changes in expected credit loss will have a direct impact on P&L. The P&L volatility will, however, significantly differ per type of credit portfolio, also depending on counterparty ratings and remaining maturity. Portfolios with loans rated below investment grade will move faster from ‘state 1’ to ‘state 2’ (see box), since a move within investment grade ratings is not seen as a credit quality deterioration. Portfolios with long maturities will face large P&L volatility when moving from state 1 to state 2.

- Capital levels and deal pricing will be affected by the expected provisions.

Total P&L over time will not change, since the expected credit loss provision is booked against the actual credit losses during lifetime. If there is no actual credit loss, all provisions will fall free as profit towards maturity.

Forward-looking

IFRS 9 requires financial institutions to adjust the current backward-looking incurred loss based credit provision into a forward-looking expected credit loss. This sounds logical for an accounting provision and it assumes that existing relevant models within risk management may be applied. However, there are some difficulties to overcome.

Incorporating forward-looking information means moving away from the through-the-cycle approach towards an estimation of the ‘business cycle’ of potential credit losses. A forward-looking expected credit loss calculation should be based on an accurate estimation of current and future probability of default (PD), exposure at default (EAD), loss given default (LGD), and discount factors. Discount factors according to IFRS 9 are based on the effective interest rate; this subject will not be further addressed here. The EAD can mainly be derived from current exposure, contractual cash flows and an estimate of unscheduled repayments and an expectation of the use of undrawn credit limits. Both unscheduled repayments and undrawn amounts are known to be business cycle dependent. Forecasting these items can be derived from historical observations.

Of course, the best calibration is on defaulted data since we determine exposure at default. If insufficient data is available, cycle dependent unscheduled repayments and drawing of credit limits can be derived from the entire credit portfolio, preferably corrected with some expert judgement to reflect the situation at default.

Banks have internal rating models in place to assign a PD to a counterparty and for trenching the portfolio in different levels with a specific PD. From a capital point of view, these ratings are mostly calibrated to a through-the-cycle level of observed defaults. Now using all the bank’s forward-looking information may improve estimates if business cycle(s) can be identified, potential scenarios of the development of the cycle in the future can be forecasted, including how the cycle affects a bank’s PD term structure. This would be a macroeconomic and econometric heaven if there were sufficient data available to derive accurate and statistically significant models. Otherwise, banks need to rely more on expert judgement and external macroeconomic reports.

Next to the PD term structures, LGD term structures are required to calculate a life time expected loss. Deriving an accurate LGD term structure from realized defaults requires a large default database. Deriving a business-cycle dependent LGD term structure requires an even bigger database of accurately and timely documented losses. The level of business cycle dependency of LGD significantly differs per type of counterparty, industry, and collateral. Subordination is not much cycle dependent, while loans covered with collateral, such as mortgage loans, may result in large movements in LGDs over time. Hence, this requires different LGD term structures for different LGD types and levels.

Economic scenarios

Incorporating forward-looking information means modeling business cycle dependency in your PD and LGD. For significant drivers, future scenarios are required to calculate expected credit loss. At most banks, these forward-looking scenarios are commonly the domain of economic research departments. Macroeconomic forecasting concentrates mainly on country-specific variables. Growth of domestic product, unemployment rates, inflation indices and interest rates are typical projected variables.

Usually, only large international banks with an economic research department are able to project consistent economic outlooks and scenarios. Next to macro scenarios, industry specific forecasts are important. Industry risk models enable a bank to make forecasts for a certain industry segment, e.g. chemicals, automotive or oil & gas. Industry models are often based on variables such as market conditions, barriers to entry and default data. At some banks, industries are analyzed and scored by economic researchers. At others, usually smaller banks, industries are ranked by sector business specialists.

Industry scorings often form input for rating models and are important factors for portfolio management purposes. Therefore, caution is required in correlation between drivers of ratings and drivers of the PD term structure.

Credit portfolios

For homogenous retail exposures, forward-looking elements can be considered on a portfolio level by modeling the dependencies of PD and LGD percentages for realized defaults and losses; in essence this is a bottom-up approach. For mortgage portfolios, cycle dependency relates, for example, to unemployment and house price indices, among other factors. However, statistically significant parameters and models for default relations are difficult to obtain since there is a common time gap in observing and administrating both defaults and business cycle.

Model significance can be improved by adding additional variables with increasing risk of overfitting. Even if there is statistical proof for macroeconomic dependencies in PD and LGD rates, it is advised to be cautious, since it also requires designing credible macroeconomic scenarios. As business cycles are difficult to predict, this could lead to extra P&L volatility and an increase in the complexity and ‘explainability’ of figures. Therefore, regular back-testing and continuous monitoring are important for an accurate and robust provision mechanism, especially in the first years after the model is introduced.

For non-retail exposures, country and industry risk are, if embedded in the credit rating models, already part of the annual individual credit review and rating assignment processes. In the monthly financial reporting, additional country and industry risk factors can be taken into account on a portfolio basis, making provisions more forward looking; in essence a top-down approach. If necessary, risk management can make adjustments on an individual basis for wholesale counterparties, and facilities. A forward-looking overlay should improve the accuracy of provisions and a timely and adequate recognition of credit risk, instead of “too little, too late” as under the existing rules.

Governance

Because of the forward-looking character of IFRS 9, and the increasing role of risk models, a transparent and robust governance framework will become more important. Coordination and communication are required across risk, finance, business units, audit and IT.

Risk management typically delivers the expected credit loss parameters and calculations to finance on a monthly basis. Proposals for retail and nonretail adjustments briefly described above, must be discussed and agreed upon, after which the final proposal is submitted to the approval authority.

The governance framework should be documented and reviewed on an annual basis, and highlight key functions, stakeholders, definitions, data management, model (re)development, model implementation, portfolio monitoring and validation. In addition, all parties involved should speak the same credit risk language, have access to detailed data underlying the calculation of the provision and a good under- standing of the model and implications of decisions and parametrization. Only then can the finance department obtain an accurate understanding of the level and change of the provision and clearly inform the board and other stakeholders.

Zanders recommends preparing early for IFRS 9 and having a deep and thorough understanding of the impact, as well as the robust tooling and processes in place. Don’t just wait and ‘watch the hare running’, but start early, and at least run a shadow period during daylight to allow sufficient time.

Hassle-free CECL and IFRS9 compliance? Try our new Condor ECL tool!

Compared with only a few years ago, today’s corporate treasurers are exposed to a much greater variety of counterparty risks within both their supply chains and financial institutions. This article provides guidance on how these counterparty risks can be effectively monitored and managed.

In recent years, the counterparty risks that corporates are exposed to have dramatically changed. Besides the traditional default risk that corporates hold on their customers, there has been an increase in counterparty risk regarding the exposures to financial institutions (FIs), the total supply chain, and also to sovereign risk. Market volatility remains high and counterparty risk is one of the top risks that need to be managed. Any failure in managing counterparty risk effectively can result in a direct adverse cash flow effect.

There are two important factors that have resulted in greater attention being paid to counterparty risk related to FIs in treasury. Firstly, FIs are no longer considered ‘immune’ to default. Secondly, the larger and better-rated corporates are now hoarding a day’s more cash compared to their pre-2008 crisis practice, due to restricted investment opportunities in the current economic environment, limited debt redemption and share buy-back possibilities and the desire to have financial flexibility.

Several trends can be identified regarding counterparty risk in the corporate landscape. In a corporate-to-bank relationship, counterparty risk is being increasingly assessed bilaterally. For example, the days are over when counterparty risk mitigating arrangements, such as the credit support annex (CSA) of an International Swaps and Derivative Association (ISDA) agreement, were only in favor of FIs. Nowadays, CSAs are more based on equivalence between the corporate and FI.

Measuring and Quantifying of Counterparty Risks

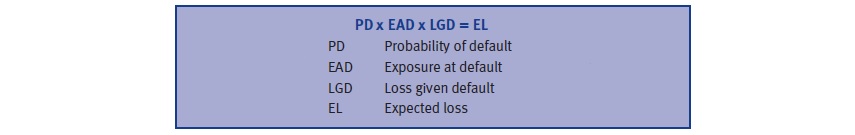

The magnitude of counterparty risk can be estimated according to the expected loss (EL), which is a combination of the following elements:

- Probability of default (PD): The probability that the counterparty will default.

- Exposure at default (EAD): The total amount of exposure on the counterparty at default. Besides the actual exposure the potential future exposure can also be taken into account. This is the maximum exposure expected to occur in the future at a certain confidence level, based on a credit-at-risk model.

- Loss given default (LGD): Magnitude of actual loss on the exposure at default.

This methodology is also typically applied by FIs to assess counterparty risk and associated EL. The probability of default is an indicator of the credit standing of the counterparty, whereas the latter two are an indicator of the actual size of the exposure. Maximum exposure limits on the combination of the two will have to be defined in a counterparty risk management policy.

Another form of counterparty risk is settlement risk, or the risk that one party of the agreement does not deliver a security, or its value in cash, as per the agreement after the other party has already delivered the security or cash value. Whereas EAD and LGD are calculated on a net market value for derivatives, settlement risk entails risk to the entire face value of the exposure. Settlement risk can be mitigated, for example by the joining multicurrency cash settlement system Continuous Link Settlement (CLS), which settles gross transactions of both legs of trades simultaneously with immediate finality.

Counterparty Exposures

In order to be able to manage and mitigate counterparty risk effectively, treasurers require visibility over the counterparty risk. They must ensure that they measure and manage the full counterparty exposure, which means not only managing the risk on cash balances and bank deposits but also the effect of lending (the failure to lend), actual market values on outstanding derivatives and also indirect exposures.

Any counterparty risk mitigation via collateralisation of exposures, such as that negotiated in a CSA as part of the ISDA agreement and also legally enforceable netting arrangements, also has to be taken into account. Such arrangements will not change the EAD, but can reduce the LGD (note that collateralisation can reduce credit risk, but it can also give rise to an increased exposure to liquidity risk).

Also, clearing of derivative transactions through a clearing house – as is imposed for certain counterparties by the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) – will alter counterparty risk exposure. Those cleared transactions are also typically margined. Most corporates will be exempted from central clearing because they will stay below the EMIR-defined thresholds.

It will be important to take a holistic view on counterparty risk exposures and assess the exposures on an aggregated basis across a company’s subsidiaries and treasury activities.

Assessing Probability of Default

A good starting point for monitoring the financial stability of a counterparty has traditionally been to assess the credit rating of the institutions as published by ratings agencies. Recent history has proved however that such ratings lag somewhat behind other indicators and that they do not move quickly enough in periods of significant market volatility. Since the credit rating is perceived to be somewhat more reactive they will have to be treated carefully. Market driven indicators, such as credit default swap (CDS)* spreads, are more sensitive to changes in the markets. Any changes in the perceived credit worthiness are instantly reflected in the CDS pricing. Tracking CDS spreads on FIs can give a good proxy of their credit standing.

How to use CDS spreads effectively and incorporate them into a counterparty risk management policy is, however, sometimes still unclear. Setting fixed limits on CDS values is not flexible enough when the market changes as a whole. Instead, a more dynamic approach that is based on the relative standing of an FI in the form of a ranking compared to its peers will add more value, or the trend in the CDS of a FI compared against that of its peers can give a good indication.

A combination of the credit rating and ‘normalised’ CDS spreads will give a proxy of the FI’s financial stability and the probability of default.

Counterparty Risk Management Policy

It is important to implement a clear policy to manage and monitor counterparty risk and it should, at the very least, address the following items:

- Eligible counterparties for treasury transactions, plus acceptance criteria for new counterparties – for example, to ensure consistent ISDA and credit support agreements are in place. This will also be linked to the credit commitment. Banks which provide credit support to the company will probably also demand ancillary business, so there should be a balanced relationship. While the pre-crisis trend was to rationalise the number of bank relationships, since 2008 it has moved to one of diversification. This is a trade-off between cost optimisation and risk mitigation that corporates should make.

- Eligible instruments and transactions (which can be credit standing dependent).

- Term and duration of transactions (which can be credit standing dependent).

- Variable maximum credit exposure limits based on credit standing.

- Exposure measurement – how is counterparty risk identified and quantified?

- Responsibility and accountability – at what level/who should have ultimate responsibility for managing the counterparty risk.

- Decision making to provide an overall framework for decision making by staff, including treatment of breaches etc.

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) – Selection of KPIs to measure and monitor performance.

- Reporting – Definition of reporting requirements and format.

- Continuous improvement – What procedures are required to keep the policy up to date?

Conclusion

To set up an effective counterparty risk management process, there are five steps to be taken as shown below; from identifying, quantifying, setting a policy to process and execute the set policy regarding counterparty risk.

Treasurers should avoid this becoming an administrative process; instead it should really be a risk management process. It will be important that counterparty risk can be monitored and reported on a continuous basis. Having real-time access to exposure and market data will be a prerequisite in order to be able to recalculate the exposures on a frequent basis. Market volatility can change exposure values rapidly.

* A credit default swap protects against default. In the event of a default the buyer will receive compensation. The spread (CDS spread) is the (insurance) premium paid for the swap.