The recent rises in global interest rates mark the first raise in a long time, as the loose monetary policies and quantitative easing (QE) introduced after the 2008 crash and Covid-19 pandemic abate.

There is now a clear trend break that is likely to significantly impact financial markets. Rate hikes have already caused rises in the mortgage rates offered by banks, but variable rate savings are still negligible in the eurozone. However, when you look further east, the first glimpses of positive compensations for client deposits are evident. What can we learn from Poland in this new and recently uncharted market territory?

Since the beginning of this year, interest rates are increasing at a fast pace after a long period of low rates. The Bank of England and the US Federal Reserve have already hiked their rates in an effort to tame high inflation, while the European Central Bank (ECB) has just announced it plans to up rates after 11 years of historically low or even negative interest rates. The consensus on financial markets is that positive rates will return in the eurozone towards the end of this year.

Looking towards Eastern Europe might offer a glimpse into the future for banks and their clients, as they are already ahead of the curve in terms of rising interest rates.

THE POLISH EXEMPLAR

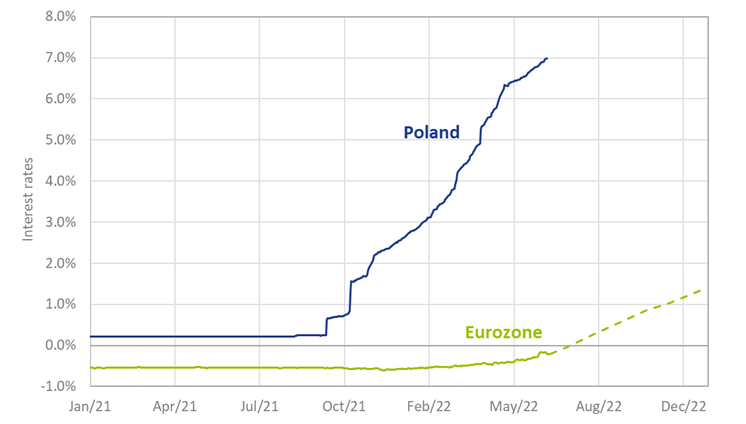

Where interest rate hikes have only just been announced within the 19-nation eurozone, the markets in Hungary, Romania, Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe that remain outside the single currency are already in front of the trend. In Poland, for example, interest rates decreased to near-zero after the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, driving down mortgage and savings rates to historically low levels. Due to high inflation, however, the Polish central bank has increased rates sharply since October of last year. As a result, short term rates in Poland have risen by almost 7% since the end of 2021, while the eurozone rates are only expected to increase in the coming months (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Three-month interest rate in Poland v the eurozone, including implied future rates for the eurozone (dashed line)

Polish consumers hoping for a similarly fast increase in their savings rate were left disillusioned. Since interest rates started to rise nine months ago in the country, savings rates have remained at a constant level of 0.5%, resulting in an extreme increase in margins for Polish banks. Since the majority of Polish mortgage owners pay a variable mortgage rate, rising interest rates have put a squeeze on many households.

As a reaction, the Polish government publicly urged banks to further increase the savings rate paid to consumers. Indeed, the National Bank of Poland recently began offering its own savings bonds directly to consumers. Retail clients are able to invest their savings for a fixed term against a coupon which tracks the central bank’s rate. As hoped, this has encouraged a response from the Polish banks. They are now providing similar fixed term deposits to clients.

Upward pricing pressure on savings rates is now evident. Recently, multiple banks announced a small raise of the general savings rate, towards 1%, slowly passing on some of the additional margin to clients. However, savings rates on offer in Poland still significantly lag the short-term interest rates in the market.

ARE POLISH TRENDS APPLICABLE TO EURO MARKETS?

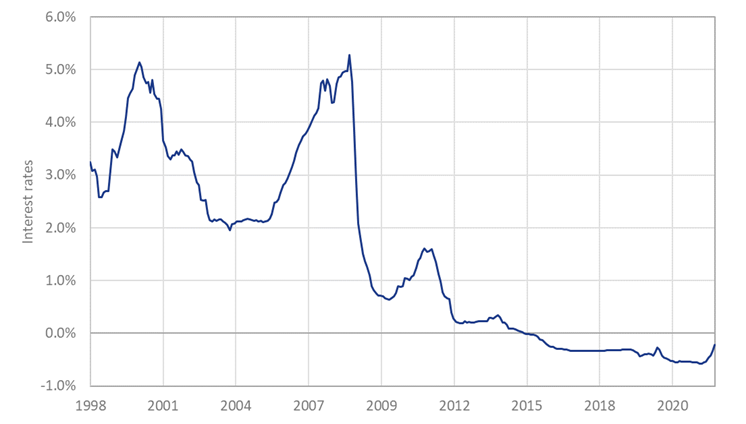

Although Eastern European markets provide interesting insights into interest rate developments, it doesn’t necessarily provide a clear roadmap for Western European markets. Eastern markets on the continent have experienced a relatively low interest rate environment for a long time, but historically interest rates have been significantly higher when compared to the eurozone. Since the introduction of the Euro, interbank offered rates have hardly ever risen above 5% (see Figure 2). It remains to be seen, therefore, whether euro yields will rise to the same extremes currently observed in Eastern Europe.

Figure 2: Historical interbank rates for the eurozone

Banks in the euro area face more competition making it challenging to maintain a savings margin that is similar to the Polish banks. Eurozone banks face more competition from peers within their own country and from foreign banks that can more easily operate in the single currency area. Those with their own domestic currencies face less displacement risk. Next to that, eurozone backs face more competition from newer Fintech-enabled banks that spy an opportunity to conquer market share by offering higher savings rates. Waiting too long to raise the compensation of depositors could lead to a large exodus of retail clients from traditional institutions.

It is unlikely that the ECB will take a similarly active role to the National Bank of Poland in pressuring banks to increase savings rates. ECB policies must be appropriate for all the 19 nation marketplaces within the eurozone, which generally exhibit less uniformity than the Polish market.

For example, the intervention of the National Bank of Poland resulted from the large portion of variable rate mortgages in Poland, but the eurozone market is much more diversified in this respect . It is therefore not expected that the ECB will start offering retail products to increase savings rates.

Although the ECB is planning to hike its interest rates in common with its Eastern European neighbors, a continuous series of significant rate hikes is less likely because financial markets tend to react stronger to expectations or announcements from the ECB, which necessitates a more graduated approach. The point is illustrated by the significant increase in the spread between Italian and German obligations seen following the recent announcement that the ECB will raise interest rates for the first time in 11 years. The foreshadowed change decreased the value of Italian obligations immediately. Some divergence with the trend observed in Poland is therefore inevitable, but the over-arching pattern of rising global rates is evident and over time this will course feed into savings rates with some local variations.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM SAVINGS MARKETS IN OTHER COUNTRIES?

Despite the differences between savings markets in Eastern Europe and the eurozone, there are plenty of lessons that we can still learn from the Polish situation. Interest rate hikes in the market will likely predate the increasing of deposit rates, although the lag between the two is likely to vary due to differences in the competitive environment.

In Poland, the savings rates offered by banks are slowly rising after more than six months of high short-term interest rates. This makes it unlikely that we will see large increases in deposit rates in the eurozone before the end of the year if we map that trend across the currency border.

While the approach of the ECB to interest rate hikes is less hawkish compared to the Eastern European central banks, there will still be multiple rate increases over the coming year. In the Polish market, the pressure to increase rates on savings deposits mostly came from a competitive price on fixed term deposits – in this case offered by the central bank itself. Although the ECB is unlikely to adopt such an active approach, the pricing pressure in the eurozone is likely to come from term deposits as well. Once the difference between short term rates, which are typically reflected in fixed term deposits, and rates on savings becomes large enough, banks are likely to increase their compensation on savings – or face a declining customer base.

From the banks point of view, it is critical to accurately capture the pricing dynamic between fixed term deposits and saving rates. This dynamic could be modeled explicitly when forecasting deposit rates to capture the risk in variable rate savings.

One approach is to consider the forward-looking behavior of savings while calibrating the models by formulating specific scenarios and the expected pricing strategy in these scenarios. Lessons from Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe offer an interesting case study to challenge the way the bank approaches increasing interest rates.