Gaining Insights from Shorter Horizons: NGFS’s New Short-Term Scenarios

To help banks manage climate risk over a more relevant time horizon, the NGFS has introduced scenarios focused on the next three to five years.

With extreme weather events becoming more frequent and climate policy tightening across jurisdictions, banks are under increasing pressure to understand how climate change will impact their portfolios. Previously, most climate scenario analyses have focused on long-term trajectories, stretching out to 2050 or beyond. However, these long-term analyses have often been far too abstract for day-to-day risk management.

The new NGFS short-term scenarios investigate the impact of climate risks over the next five years, offering a more practical solution. By isolating the individual impacts from physical and transition risk, and by providing better granularity at both temporal and sectoral levels, the new scenarios provide a new and valuable tool for climate risk modelling.

In this article, we explore what makes these scenarios unique, their benefits and limitations, their impact on future macroeconomic and market trends, and importantly, how banks can utilize them to fulfil regulatory requirements.

Physical and transition risks in the scenarios

The short-term scenarios capture four possible futures, each reflecting a different mix of physical and transition risks. The scenarios show how varying levels of climate policy and climate-related events could shape the economic and financial outcomes over the next 5 years. The four scenarios are summarized in the figure below.

Figure 1: The four NGFS short-term scenarios.

Key benefits and limitations of the new scenarios

The scenarios offer several benefits, including a more practical time horizon and better isolation of physical and transition risks. However, they also come with inherent limitations that should be acknowledged when being used. Below, we summarise the main benefits and limitations of the new scenarios.

Benefits

- Time horizon

- Although NGFS has already released several versions of their long-term scenarios, this is the first release of climate scenarios whose narratives focus on the next few years. Short-term scenarios cover time horizons that are typically more relevant for risk assessment management in banks, such as capital planning, liquidity assessments, and regulatory stress testing exercises. In addition, the uncertainty of climate and macroeconomic variables increase over longer horizons, making the short-term scenarios more dependable.

- Calibrated using recent data

- As with any model which has been recalibrated using the latest data, by incorporating the most recent economic conditions, market trends, and climate policy commitments, the short-term scenarios provide more reliable and accurate forecasts. This allows banks to run more credible stress tests, develop informed strategies, and leads to outputs that are more aligned with current market and policy conditions.

- Isolation of physical and transition risk

- Three of the four scenarios isolate only physical or transition risk, which can provide more targeted insights for climate risk assessment. By separating these risks, banks can identify the specific drivers of financial impact more accurately, whether from policy changes or climate-related events. Unlike scenarios that contain a combination of transition and physical risks, isolating only one of the risks can make the results easier to interpret and act upon.

- Variation across sectors and regions

- NGFS short-term outputs cover up to 15 macro-regions (e.g. EU27, Asia and North America) and up to 46 countries, which is similar to the long-term scenario results. The biggest improvement is found on the temporal granularity: while most of the variables for the long-term scenarios are provided in 5-year intervals, the short-term scenarios are mostly provided on a yearly basis.

Limitations

- Still not short enough?

While the NGFS short-term scenarios aim to address near-term climate-related risks, even shorter time horizons may be necessary for accurate and practical modelling in both credit and, in particular, market risk. More granular timeframes, such as a quarterly projection interval, would support banks to rapidly react to policy changes, market reactions, or acute physical climate events, which can unfold within weeks or months and not years.

- Lack of dispersion within regions or sectors

In some cases, the results show limited differentiation between sectors and regions. This can make it difficult to accurately capture sector-specific or country-specific vulnerabilities. For example, countries with significant geographical and socioeconomic differences, such as Switzerland, Iceland, and Ukraine, are grouped together under the region "Rest of Europe". Similarly, the sector "Market Services" includes a wide range of distinct industries, such as Real Estate, Telecommunications, and Waste and Water Collection.

- Physical risk is still difficult to accurately model

Accurately capturing physical climate risk within a short-term horizon remains methodologically challenging. Acute events like floods or wildfires are based on the estimation of tail risks (e.g. return periods) which can be difficult to model accurately. In addition, physical risks exhibit high spatial variability. For instance, coastal areas can be more vulnerable to hurricanes than inland areas, even if they are in the same country. Therefore, aggregating scenario data on the country or regional level can potentially underestimate the risks in specific areas.

- Over-simplification of policy implementation

Policy pathways in the short-term scenarios tend to assume smooth, linear implementation and immediate effectiveness. In reality, climate policies often face political, social, and economic frictions that delay or prolong their impact. Hence, these assumptions may lead to the underestimation of transition shocks, particularly where abrupt or uncoordinated policy actions could trigger market volatility.

Impact of the new scenarios on important modelling variables

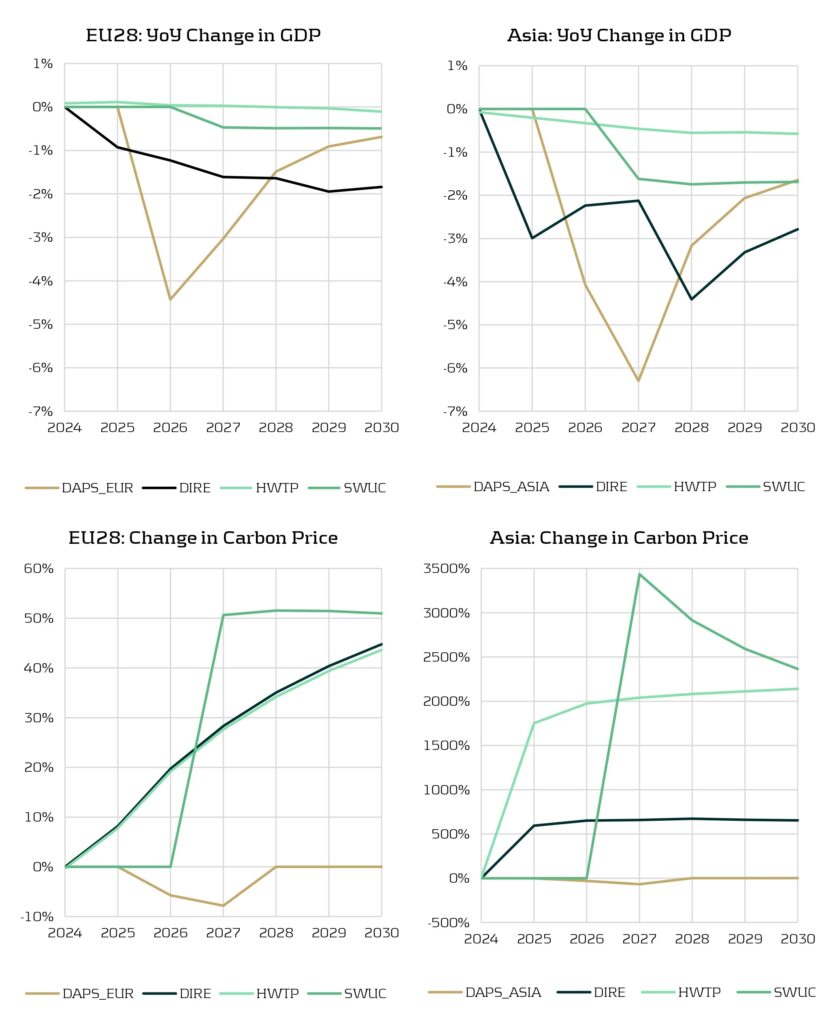

To take a look at the NGFS short-term scenarios in action, we can examine the impact of the scenarios on key macroeconomic variables. Figure 2 shows the behavior of GDP and carbon price (with respect to baseline values) within Europe and Asia for all four scenarios. There are clear negative shocks which are seen in the GDP for all the scenarios. Similarly, we see a positive spike in the carbon price for both regions, however the effect in Asia is much greater than in Europe. Asia experiences a sharper percentage increase in carbon prices because it starts from a much lower baseline compared to Europe, where carbon prices are already high and policies have been in place for years. Additionally, in general, Asia is more emissions-intensive and heavily reliant on fossil fuels (particularly coal) which means more aggressive changes to carbon pricing are required to reduce emissions.

Figure 2: Top – YoY change in GDP (compared to baseline). Bottom – change in carbon price (compared to baseline).

Although the impact to variables such as macroeconomic indicators, emissions trends, and shifts in production offer essential context, they are usually only the first step in climate risk modelling. Ultimately, we are interested in how these variables translate into changes in market-based metrics, such as corporate bond spreads or PDs, which directly affect portfolio valuation. For example, for stress testing purposes, macro and sectoral outputs must be mapped onto these market-based metrics to assess potential losses and capital impacts.

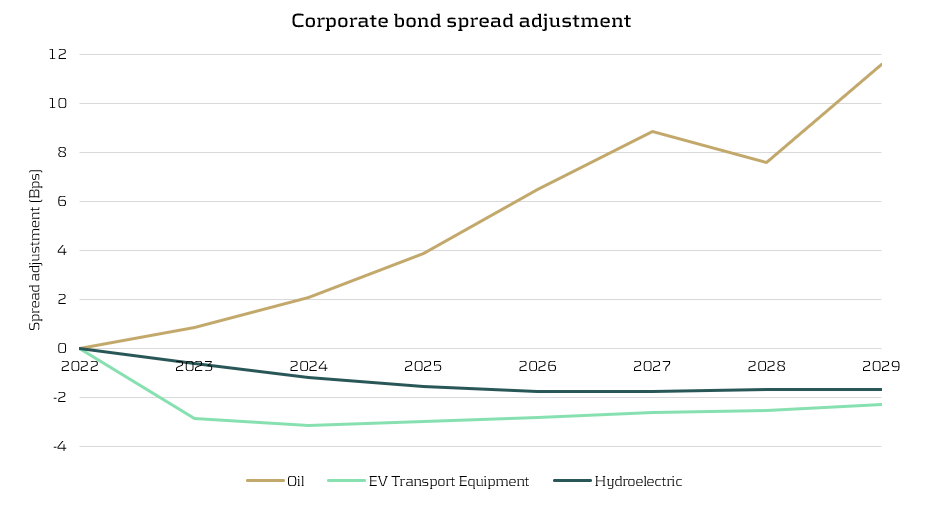

Figure 3 compares the corporate bond spread adjustments for the Oil, EV Transport Equipment, and Hydroelectric sectors under the HWTP scenario. The results illustrate a shifting investor sentiment in the corporate bond market. The Oil sector experiences a significant increase in spread adjustments over the time horizon due to an increase in perceived risk and a decline in investor favorability. In contrast, the EV Transport Equipment and Hydroelectric sectors maintain negative spread adjustments, highlighting that they are viewed more favorably. Overall, these results capture a market preference for cleaner and more sustainable industries and the scenarios clearly distinguish between sectors that are carbon-intensive and those aligned with low-carbon technologies.

Figure 3: Adjustment to corporate bond spreads for the Oil, EV Transport Equipment, and Hydroelectric sectors (HWTP scenario).

Zanders’ opinion

Although the five-year horizon of the new scenarios is still somewhat too long for direct application to market risk modelling (where exposures fluctuate on much shorter timescales), it aligns far better with the lifecycle of most credit products, especially those with relatively short maturities such as personal loans. Banks should utilise the scenarios as starting points for modelling the effects of near-term climate shocks on the performance of their credit products. However, the new scenarios can still provide valuable insights for market risk modelling. The scenarios can help identify sectoral sensitivities, adjust volatility and correlation assumptions, and enrich the narratives of existing scenarios.

The scenarios also help to standardise climate stress testing by providing a consistent set of assumptions, variables, and modelling frameworks that financial institutions can use as a common reference. This alignment reduces discrepancies in inputs and methodologies, enabling more comparable results across banks and jurisdictions. As a result, institutions and supervisors can more effectively benchmark climate-related risks, identify outliers, and support coordinated regulatory responses, ultimately improving the credibility and usefulness of climate stress tests.

Importantly, the new scenarios are well-suited to meet the needs of regulatory frameworks like the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP), which typically considers a 3-to-5-year horizon. This makes them far more applicable than traditional long-term scenarios, which typically look out to 2050. Similarly, the ECB climate stress testing framework requires banks to use a variety of time horizons and both physical and transition risk scenarios. With ever-growing regulatory expectations, such as the recent CP10/25 consultation paper from the PRA on managing climate-related risks, the new short-term scenarios provide a timely and relevant tool for banks.

Conclusion

The new NGFS short-term scenarios are an important addition to climate risk modelling frameworks, offering a direct focus on the next five years – a time period which is far more aligned with capital planning, liquidity assessments, and regulatory stress. However, the scenarios are not intended to replace existing long-term scenarios. Rather, they complement them by providing a near-term view of climate risk that is highly relevant for all banks.

For more information on how Zanders can support you to understand the impact of climate risk on your business, please contact Steyn Verhoeven and Polly Wong.

Navigating the Dutch National Mortgage Guarantee (NHG) in CRR3

A regulatory change in CRR3 may significantly impact the capital treatment of NHG-covered Dutch mortgages.

With the introduction of CRR3, effective from January 1, 2025, the ‘extra’ guarantee on Dutch mortgages – known as the Dutch National Mortgage Guarantee (NHG) – will no longer be automatically eligible for the modelling approach. This requires institutions to apply the substitution approach instead. Although this may seem like a minor change, it can have far-reaching consequences. In this article, we provide a background on this change in the treatment of NHG and discuss the potential implications and challenges it may bring.

Introduction Dutch National Mortgage guarantee (NHG)

The Dutch National Mortgage Guarantee (NHG) serves as a safety net for borrowers and lenders of mortgage loans in the Netherlands. It is designed to provide protection in cases of financial distress caused by circumstances such as divorce, disability, or unemployment [1] [2] [3]. If these situations require the sale of the residential property and a residual debt remains after all other collection sources have been exhausted, the NHG will cover this remaining debt when contractual conditions are met1.

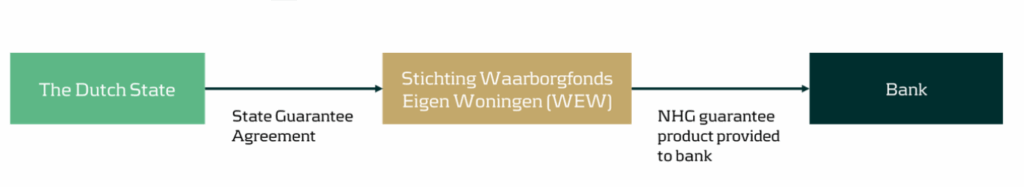

The NHG guarantee is provided by the Stichting Waarborgfonds Eigen Woning (WEW) [1] [4]. Although Stichting WEW is not state-owned, the Dutch state acts as a suretyship provider. This arrangement ensures that if Stichting WEW’s capital is insufficient to meet its guarantee claims, the state will supply unlimited interest-free loans. These loans must be repaid only after the foundation’s assets have been restored [5].

Following the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), the NHG guarantee classifies as Unfunded Credit Protection (UFCP) Credit Risk Mitigation (CRM) and should be treated accordingly.

Exposure class of Stichting WEW

As outlined in the previous text, the direct protection provider of the NHG is Stichting WEW. In the event that NHG fails to make payments, the Dutch sovereign state provides a suretyship to Stichting WEW, essentially serving as a counter-guarantee for the NHG guarantee extended by Stichting WEW.

CRR III article 4(8) [6] defines a public sector entity (PSE) as: “a non-commercial administrative body responsible to central governments, regional governments or local authorities, or to authorities that exercise the same responsibilities as regional governments and local authorities, or a non-commercial undertaking that is owned by or set up and sponsored by central governments, regional governments or local authorities, and that has explicit guarantee arrangements, and may include self-administered bodies governed by law that are under public supervision;”

Stichting WEW satisfies the definition of PSE in CRR III article 4(8), as it is a non-commercial undertaking (stichting) established2 by the central government, with an explicit guarantee arrangement from the Dutch central government. However, the CRR does not clearly define the sponsoring of the central government. Should it be determined that the sponsoring requirement is not met, Stichting WEW must instead be classified as a corporate exposure class3.

The remainder of the text assumes that Stichting WEW can be classified under the PSE exposure class as defined in CRR III article 112(c) (SA) and 147(2)(aa)(ii) (IRB). Nonetheless, the validity of the arguments throughout the following chapters remains intact, regardless of whether Stichting WEW is classified under the corporate or PSE exposure class.

Stichting WEW may not be classified as an exposure to a central government following CRR III articles 116 (SA) and 147(3)(a) (IRB), which specify that only specific public sector entities should be allocated to the central government exposure class. Given that Stichting WEW does not appear on the list published by the European Banking Authority (EBA) [7], it cannot be classified as an exposure to the central government under these articles.

There is no market consensus in the Dutch mortgage market on how to classify Stichting WEW: whether as a PSE or as a Corporate exposure. During our recently hosted roundtable discussing the implications of regulatory changes concerning NHG, participating banks indicated that it might be challenging to clearly classify Stichting WEW as a PSE due to the inconclusive regulatory guidance noted in this chapter. Banks are encouraged to engage in discussions with their Joint Supervisory Team (JST) and/or National Competent Authority (NCA) to determine the appropriate treatment of Stichting WEW.

Allowed UFCP approaches for NHG guarantees

According to CRR III article 108(3), if the AIRB approach is used for similar direct exposures to the protection provider, the UFCP modelling approach is required. In this context, similar direct exposure refers to exposure to the Stichting WEW4. With the competent authorities’ approval, the AIRB approach can be used for PSEs (and corporates), as specified in CRR III article 151(8-9). Therefore, if the AIRB approach is used for exposures to Stichting WEW, then the UFCP modelling approach is applicable. Conversely, if the SA or FIRB approach is used instead, then the UFCP substitution approach is mandatory.

Applying the effect of NHG guarantees

Under the substitution approach, the counter-guarantee provided by the Dutch central government can be recognized. CRR III article 214 states that guarantees backed by the central government may be treated as exposures within the central government exposure class, as defined in CRR III articles 112(a) (SA) and 147(2)(a) (IRB). This implies that the NHG guarantee can be classified under the central government exposure class [8]. Consequently, while capitalizing the NHG guarantee using the SA approach for the Dutch central government, it is possible, though not obligatory, to apply a 0% risk weight associated with the Dutch central government5.

If the institution employs the AIRB approach for exposures to to Stichting WEW, the modelling approach can be applied. In this scenario, risk weights for Stichting WEW and the Dutch central government (CRR article 214) are not used, as the effect of the NHG guarantee is modelled directly.

Substitution approach for banks without AIRB PSE models

For banks without AIRB models for Stichting WEW, the above argumentation does not apply, and the UFCP substitution approach for NHG presents several challenges.

The following list provides a non-exhaustive overview of these challenges:

1. Reconsideration of methodologies: Many banks model NHG separately, possibly through a specifically calibrated segment.

2. Level of application: Implementing the substitution approach within the reporting stream poses difficulties, as it requires separating the NHG-covered portion of the exposure from the uncovered portion. This could necessitate changes in data delivery and processing.

3. Changing coverage amounts over time: The NHG coverage percentage has changed from 100% to 90%, requiring at least two different implementations/calculations.

4. Unknown claimable amount: The exact amount that can be claimed is only known once the residential property is sold.

5. Loss-sharing exclusion: The substitution approach cannot incorporate the loss-sharing characteristic.

6. Mismatch between 0% substitution and actual losses of 5-10%: This is typically due to:

- Failed NHG claims, which cannot be integrated into the substitution approach.

- Discounting of cash-flows.

In summary, the substitution approach for banks without AIRB PSE models presents significant practical and methodological challenges. Effectively addressing these is essential to ensure a reliable implementation of the revised NHG treatment and maintain regulatory compliance.

Conclusion

Although the change in the CRR may seem minor at first glance, its consequences can be far-reaching. This article has outlined the key aspects of the revised NHG treatment, along with potential implications and challenges. However, it is not possible to provide a one-size-fits-all overview that fully captures the impact for every financial institution affected by this change.

If you would like to understand what the revised NHG treatment means specifically for your organization, feel free to contact our experts: Rick Stuhmer & Victor van Dongen.

Bibliography

[1] NHG, „Voorwaarden en normen [NHG conditions 2024],” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/voorwaarden-en-normen/#id-18478.

[2] NHG, „Kwijtschelding van een restschuld [NHG conditions 2024],” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/hulp-van-nhg/kwijtschelding-van-een-restschuld/.

[3] Rijksoverheid, „Nationale Hypotheek Garantie (NHG),” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/huis-kopen/vraag-en-antwoord/nationale-hypotheek-garantie-nhg.

[4] NHG, „Over de stichting [NHG annual report 2022],” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/media/1bgf13fd/nhg_jaarverslag2022-hr.pdf.

[5] Stichting Waarborgfonds Eigen Woningen, „Memorie van toelichting bij de Wet herziening eigendomsgrenzen 2023, onderdeel 1477577. Rijksfinanciën.,” 2023. [Online]. Available here.

[6] European Parliament and European Council, „Amending Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 as regards requirements for credit risk, credit valuation adjustment risk, operational risk, market risk and the output floor,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401623.

[7] European Banking Authority, „Lists for the calculation of capital requirements for credit risk,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.eba.europa.eu/activities/supervisory-convergence/supervisory-disclosure/rules-and-guidance.

[8] Nauta Dutilh, „Toelaatbaarheid Nationale Hypotheek Garantie als kredietprotectie onder de CRR,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/media/rhkhtqbx/nhg-memorandum-over-crr-toelaatbaarheid-31-maart-2020-pdf.pdf

[9] Stichting Waarborgfonds Eigen Woningen, „Statuten NHG,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhg.nl/media/4vvcjw4p/statuten-wew-per-23-december-2019.pdf

- As of January 2014, a 10% loss sharing rule was introduced, meaning NHG guarantees only 90% of the residual debt. ↩︎

- NHG statutes article 11 allow Dutch ministers to appoint 3 out of 5 members of the supervisory board, which together appoint the 6th member. This effectively means that the Dutch government controls 4 out of 6 members [9]. ↩︎

- As fallback, Stichting WEW must be allocated to the corporate exposure class following CRR III article 147(7). ↩︎

- Article 214 does not influence the exposure class of direct exposure to the protection provider, only the exposure class of the NHG guarantee itself. ↩︎

- The alternatives are not recognizing the counter-guarantee, and either using the 20% risk weight implied by Stichting WEW’s AAA rating following CRR III article 116 using the SA approach, or using the IRB risk weight of Stichting WEW using the IRB approach. Both will lead to higher risk weights than 0% and lead to higher capital requirements. ↩︎