EBA’s Revised Definition of Default

The EBA is proposing key changes to its definition of default guidelines, with implications for credit risk practices.

On July 2nd, the European Banking Authority (EBA) published a Consultation Paper proposing amendments to its 2016 Guidelines on the application of the definition of default (DoD). As part of the consultation process, open until 15 October 2025, the credit risk specialists at Zanders will submit a formal response, leveraging our extensive experience in DoD regulation and implementation.

In this article, we share our perspective on three of the EBA’s proposed amendments, focusing on the potential impact and implementation challenges for institutions:

- We expect that a shorter probation period for forbearance measures (that only alter the repayment schedule leading to a NPV loss not greater than 5%) are expected to provide incentives for banks to opt for those types of measures rather than the most sustainable ones.

- We recommend the EBA to implement EU wide DoD guidelines they considered for payment moratoria (similar to the one for Covid), whereas the EBA proposes not to. Zanders would approve permanent moratoria guidelines, as it clarifies if governmental moratoria introduced for climate risk related natural disasters should be regarded as forbearance.

- We are oncerned that the proposal to consider material arrears on non-recourse factoring exposures up to 90 (instead of 30) DPD as technical past due situations could result in an undesired increase in the percentage of IFRS stage 1 exposures migrating directly to stage 3 (impairment).

The following chapters elaborate on these three proposed amendments in more detail.

Forbearance

The first amendments addressed in the EBA’s consultation paper (CP) are related to forbearance. The supervisory authority explains that an increase of 1% threshold for a diminished financial obligation (DFO) to 5% was considered for certain forbearance measures. This follows from the European Commission’s mandate that the update of the EBA guidelines on DoD“… shall take due account of the necessity to encourage institutions to engage in proactive, preventive and meaningful debt restructuring to support obligors.”1

In the EBA’s current DoD guidelines (DoD GL), a forbearance measure leading to a 1% or more DFO results in a default classification, which could discourage institutions from applying these measures. However, the CP purposefully proposes to exclude an increase to a 5% DFO threshold, since institutions can already implement strict(er) forbearance definitions (i.e. for concession, financial difficulty) to prevent undue default classifications. Instead, the EBA proposes to shorten the probation period from 12 to 3 months for forbearance measures that: (1) only lead to suspensions or postponements and not e.g. changes to the interest rate or exposure amounts and (2) leading to less than 5% DFO loss.

This treatment will likely incentivize institutions to choose forbearance measures in scope of the shorter probation period, rather than the ones that would be optimal for a “sustainable performing repayment status” of the obligor. The latter would be in line with the EBA’s own requirements on the management of forborne exposures (Par. 125 EBA/GL/2018/06). Furthermore, the fact that the EBA does not set the “predefined limited period of time” for the measures in scope could lead to RWA variability, as some institutions may apply the shorter probation period to longer duration forbearance measures than others. For example, if Bank A sets the limited period of time to 6 months, they can apply the shorter probation period more often compared to Bank B, which sets the period of time at 3 months. Finally, it appears as if the proposal of the banking authority aims at favouring granting forbearance measures in scope to obligors with short-term (rather than structural) financial difficulties. That is, the EBA explains that the forbearance measures in scope of the shorter probation period treatment “… would most likely be viable for obligors in temporary financial difficulties”. The shorter probation period would then lead to a return to a performing status earlier for obligors to which the forbearance measures in scope are extended, which leads to a better RWA for these obligors. Alternatively, a distinct probation period (or even higher DFO threshold) could be proposed for obligors in short-term financial difficulties, as defined in Paragraph 129(A) of the EBA’s guidelines on Management of Forborne Exposures. This would also achieve the EBA’s goal, without influencing institutions’ decision about which forbearance measure to apply.

It should be mentioned that while a large RWA impact is not anticipated from the establishment of a distinct probation period, there will likely be a significant implementation burden associated with the change. This is because, as multiple forbearance measures are usually adopted in tandem, different probation periods must be traced concurrently. The implementation of this modification would need to be retroactive, though, as credit risk models will need to be recalculated using adjusted historical data in order to account for this change. In the past, retroactively modifying the probationary period has proven to be a time-consuming and expensive problem.

Legislative payment moratoria

In light of the COVID-19 crisis, the EBA published guidelines in 2020 on handling payment moratoria introduced by governments as a means of financial aid in the context of forbearance. For certain COVID-19 measures allowing e.g. a grace period in scope of the guidelines, EBA/GL/2020/02 and amendments in .../08 and …/15, would not in itself require institutions to classify the exposures as forborne.

Even though the EBA considered introducing guidelines for potential future moratoria, the CP proposes against these changes. As one of the arguments against new moratoria guidelines, the EBA remarks that moratoria in itself will not result in DFO loss of more than 1%, hence not leading to defaults. The EBA implies that introducing new moratoria guidelines would therefore be obsolete. The EBA is also worried about RWA variability that might arise if governments declare legislative moratoria for crises in their jurisdictions. That is, the EBA expects that intra-EU comparability of RWA across institutions, might be compromised.

Adding the considered guidelines describing when moratoria should lead to forbearance in the amended DoD GL is advisable, even though the EBA proposes in the CP to remove them. Zanders challenges that guidelines describing when moratoria do not lead to forbearance would not be necessary, because the 1% DFO threshold will not be met. That is, Zanders highlights moratoria guidelines would still decide when the forborne status should be assigned to exposures if moratoria are applied. This forborne status impacts the default status later on, both for performing and defaulted exposures. The reason is that if performing forborne exposures become 30 days past due within 24 months after receiving the forborne status, a defaulted status should be assigned. If the moratoria do not lead to a forborne status, these exposures should default after becoming 90 days past due on a material amount instead. Furthermore, for defaulted exposures, it is important to understand when moratoria result in the forborne status and when they do not. That is, in order for a forborne defaulted exposure to go out of default, a substantial payment and an extended cure period are needed. Zanders would therefore be in favor of EBA guidelines that specify when moratoria should result in a forborne status and when this is not necessary.

As for the RWA variability, as self-identified by the EBA, stringent criteria could be introduced prescribing what moratoria are in scope of the amended DoD GL. As described by the EBA as well, in light of climate risk related natural disasters, payment moratoria could occur more often as a governmental means of financial aid. In contrast to ad hoc rules for each specific crisis, such as observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Zanders contends that permanently applicable moratoria instructions in the updated DoD GL will eventually lead to a more stable RWA impact when economic or natural catastrophes occur.

Days past due for non-recourse factoring

Paragraph 23(D) of the current version of the DoD guideline stipulates that in the specific situation of non-recourse factoring for which the arrears materiality threshold is breached, but none of the receivables is more than 30 days past due (DPD), should be treated as a technical past due situation. Non-recourse factoring refers to the situation where the institution (e.g. a bank) has bought receivables from its client (e.g. service provider) owed by the debtor (e.g. service consumer). The idea behind the 30 DPD is that the DPD counter might continue to increase due to a consecutive overlap in non-payments of invoices, lengthy administrative processes, and a low degree of control of the institution over the invoices.

The CP proposes to allow for up to 90 DPD to be considered technical past due situations, in correspondence to the industry requesting the EBA to be more lenient in the DoD guidelines for non-recourse factoring. This is motivated by the fact that many corporates have at least one invoice past due more than 30 days, while being rated investment grade.

Although Zanders understands corporates’ need for more leniency, allowing for up to 90 DPD to be recognized as technical past due could make stage 2 obsolete for IFRS provisioning models. That is, if material arrears on non-recourse factoring exposures should be considered technical past due for situations up to 90 DPD, the said exposures will move from 0 DPD to 91 DPD in one day. The additional lenience would break the desired flow of exposures transitioning from IFRS stage 1 (performing), first towards stage 2 (significant increase in credit risk), before going to stage 3 (credit impaired). This stage migration effect could be mitigated by another stage 2 trigger: forbearance. However, the institution cannot apply forbearance measures to a sold invoice that is due to the institution’s client, rather than due to the institution itself. Therefore, as a stage 2 trigger, forbearance cannot compensate for the lack of the30 DPD in the particular scenario of non-recourse factoring risks.

Zanders proposes to find a balance between leniency on DoD guidelines and stage migrations, by increasing the 30 days threshold. The proposed number of days should be based on an analysis of non-recourse factoring portfolios from a representative sample of supervised institutions. This analysis should then strike a balance between the average observed days past due of invoices sold on the one hand and the representativeness of IFRS stage transitions on the other hand. Zanders is convinced that amending DoD GL based on this analysis will prevent the undesired impact on IFRS provisioning models and will better fit European corporate invoicing practice.

Conclusion

In this post we analysed 3 proposed amendments from the published Consultation Paper, in which the European Banking Authority (EBA) proposes amendments to its 2016 Guidelines on the application of the definition of default (DoD). Alternatives are suggested for all 3 proposed amendments as the proposed amendments leave room for improvements .

Reach out to our experts John de Kroon and Dick de Heus, if you are interested in getting a better understanding of what the proposed amendments mean for your credit risk portfolio.

We monitor the progress of the Consultation Paper in the future. Keep a close eye on our LinkedIn and website for more information, or subscribe to our newsletters here.

- Article 178(7) CRR as amended by Regulation (EU) 2024/1623 (CRR3). ↩︎

Euro Verification of Payee – Demystifying the Real Challenge with File Based Payments

With new EU rules on instant payments taking effect in October 2025, corporates must navigate the practical challenge of applying payee verification to file-based payment processes.

The EU instant payments regulation1 comes into force on the 5th October this year. Importantly from a corporate perspective, it includes a VoP (verification of payee) regulation that requires the originating banking partner (Payment Service Provider) to validate one of the following data options with the beneficiary bank:

- IBAN and Beneficiary Name

- IBAN and Identification (for example LEI or VAT number)

This beneficiary verification must be carried out as part of the payment initiation process and be completed before the payment can be potentially reviewed and authorized by the corporate and finally processed by the originating banking partner. Now whilst this concept of beneficiary verification works perfectly in the instant payments world as only individual payment transactions are processed, a material challenge exists where a corporate operates a bulk/batch payment (file based) model.

Many large corporates will pay vendor invoices (commercial payments) on a weekly or fortnightly basis or salaries on a monthly basis. Their ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) system will complete a payment run and generate a file of pre-approved payment transactions which are sent via a secure connection to their banking partners. Typically, this automated file-based transmission contains pre-authorized transactions which has been contractually agreed with the banking partners. The banking partners will complete file syntax validation and a more detailed payment validation before processing the payment through the relevant clearing system.

If we focus on euro denominated electronic payments, these must be fully compliant with the new EU regulation from 5th October. This means the banking partners will need to verify the beneficiary information before the payment process can continue. So the banking partner will send an individual VoP check for each payment instruction contained within the payment file (batch of euro transactions) for the beneficiary bank to provide one of the following verification statuses:

- Match

- Close Match

- No Match

- Not applicable

The EU regulation then requires the banking partner to make the status available to the corporate to allow a review and approve or reject transactions based on the status that has been returned. This means there may be a ‘pause’ in the euro payments processing before the originating partner bank can proceed in processing the euro payment transactions. But this ‘pause’ may be exempted by contractual agreement, which is referred to as an ‘Opt-Out’. This is only available to corporates and covered in more detail below.

Key Considerations for the Corporate Community:

1- Notification of VoP Status: This new EU regulation will include the following status codes which will apply at a group and individual transaction level.

Group Status

RCVC Received Verification Completed

RVCM Received Verification Completed With Mismatches

Transaction Status

RCVC Received Verification Completed

RVNA Received Verification Completed Not Applicable

RVNM Received Verification Completed No Match

RVMC Received Verification Completed Match Closely

These new status codes have been designed to be provided in the ISO 20022 XML payment status message (pain.002.001.XX). However, a key question the corporate community need to ask their banking partners is around the flexibility that can be provided in supporting the communication of these VoP status codes. Does the corporate workflow already support the ISO XML payment status message and if so, can these new status codes be supported? At this stage, corporate community preference might be skewed towards leveraging a bank portal to access these new status codes, so an important area for discussion.

- Time to complete the VoP Check: The regulation includes a 5-second rule for a single payment transaction VoP request which includes the following activities:

- the time needed by the originating banking partner to identify the beneficiary bank based on the IBAN received,

- send the request to the beneficiary bank,

- beneficiary bank to check whether received info is associated to received IBAN,

- beneficiary bank to return the information,

- originating bank to return info to initiator.

If we now consider the timing based on a file of payments, the overall timing calculation becomes more challenging as it is expected originating banks will be executing multiple VoP requests in parallel. The EU regulation requires the originating banking partner to carry out the VoP check as soon as an individual transaction is ´unpacked´ from the associated batch of transactions. At this stage, a very rough estimate is that a file containing 100,000 transactions will take around 4 minutes to complete the full VoP process. But this is an approximate at this stage. The important point is that the corporate community will need to test the timings based on their specific euro payment logic to determine if existing file processing times need to be adjusted to respect existing agreed cut-off times and reduce the risk of late payments.

Corporate Action on VoP Status: This will be another area for discussion between the corporate and its banking partners, but the current options include:

- Authorize Regardless: Pre-authorise all payments, including those with mismatches.

- Review and Authorize: Review mismatches and provide explicit authorization for processing.

- Reject: mismatched payments or the entire batch.

The corporate discussion should also include how the review and approval can be undertaken. Given that the October deadline is fast approaching, the current expectation is that banking portals will be used to support this function, but this needs to be discussed including whether exceptions can be rejected individually, or if the whole file of transactions will need to be rejected. Whilst the corporate position is very clear that the exceptions only approach is required, it is still unclear if banks can support this flexibility.

Understanding the ‘Opt-Out’ Option:

Whilst the EU regulation does include an ‘opt-out’ option, meaning a VoP check will not be performed by the originating banking partners on euro transactions, this option currently only applies to bulk/batch payments and not a file containing a single payment transaction. Whilst the option to use a bank portal to make individual transactions has been suggested as a possible workaround, there is increasing corporate resistance to using bank portals given the automated secure file based processing that is now in place across many corporates.

The opt-out option needs to be contractually agreed with the relevant partner banks, so the corporate community will need to discuss this point in addition to understanding the options available for files containing single transactions, which will still be subject to the VoP verification requirement.

In conclusion

Whilst the industry continues to discuss the file based VoP model, the CGI-MP (common global implementation market practice) group which is an industry collaboration, is now recommending corporates to opt-out at this stage due to the various workflow challenges that currently exist. However, corporate and partner bank discussions will still be required around files containing single payment transactions.

There is no doubt VoP provides benefits in terms of mitigating the risk of fraudulent and misdirected payments, but the current EU design introduces material logistical challenges that require further broader discussion at an industry level.

Implications of CRR3 for the 2025 EU-wide stress test

An overview of how the new CRR3 regulation impacts banks’ capital requirements for credit risk and its implications for the 2025 EU-wide stress test, based on EBA’s findings.

With the introduction of the updated Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR3), which has entered into force on 9 July 2024, the European Union's financial landscape is poised for significant changes. The 2025 EU-wide stress test will be a major assessment to measure the resilience of banks under these new regulations. This article summarizes the estimated impact of CRR3 on banks’ capital requirements for credit risk based on the results of a monitoring exercise executed by the EBA in 2022. Furthermore, this article comments on the potential impact of CRR3 to the upcoming stress test, specifically from a credit risk perspective, and describes the potential implications for the banking sector.

The CRR3 regulation, which is the implementation of the Basel III reforms (also known as Basel IV) into European law, introduces substantial updates to the existing framework [1], including increased capital requirements, enhanced risk assessment procedures and stricter reporting standards. Focusing on credit risk, the most significant changes include:

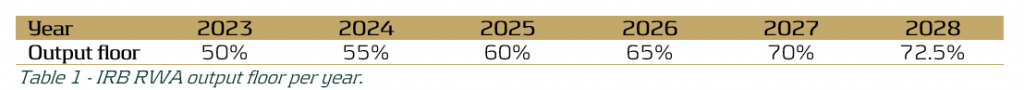

- The phased increase of the existing output floor to internally modelled capital requirements, limiting the benefit of internal models in 2028 to 72.5% of the Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) calculated under the Standardised Approach (SA), see Table 1. This floor is applied on consolidated level, i.e. on the combined RWA of all credit, market and operational risk.

- A revised SA to enhance robustness and risk sensitivity, via more granular risk weights and the introduction of new asset classes.1

- Limiting the application of the Advanced Internal Ratings Based (A-IRB) approach to specific asset classes. Additionally, new asset classes have been introduced.2

After the launch of CRR3 in January 2025, 68 banks from the EU and Norway, including 54 from the Euro area, will participate in the 2025 EU-wide stress test, thus covering 75% of the EU banking sector [2]. In light of this exercise, the EBA recently published their consultative draft of the 2025 EU-wide Stress Test Methodological Note [3], which reflects the regulatory landscape shaped by CRR3. During this forward-looking exercise the resilience of EU banks in the face of adverse economic conditions will be tested within the adjusted regulatory framework, providing essential data for the 2025 Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP).

The consequences of the updated regulatory framework are an important topic for banks. The changes in the final framework aim to restore credibility in the calculation of RWAs and improve the comparability of banks' capital ratios by aligning definitions and taxonomies between the SA and IRB approaches. To assess the impact of CRR3 on the capital requirements and whether this results in the achievement of this aim, the EBA executed a monitoring exercise in 2022 to quantify the impact of the new regulations, and published the results (refer to the report in [4]).

For this monitoring exercise the EBA used a sample of 157 banks, including 58 Group 1 banks (large and internationally active banks), of which 8 are classified as a Global Systemically Important Institution (G-SII), and 99 Group 2 banks. Group 1 banks are defined as banks that have Tier 1 capital in excess of EUR 3 billion and are internationally active. All other banks are labelled as Group 2 banks. In the report the results are separated per group and per risk type.

Looking at the impact on the credit risk capital requirements specifically caused by the revised SA and the limitations on the application of IRB, the EBA found that the median increase of current Tier 1 Minimum Required Capital3 (hereafter “MRC”) is approximately 3.2% over all portfolios, i.e. SA and IRB approach portfolios. Furthermore, the median impact on current Tier 1 MRC for SA portfolios is approximately 2.1% and for IRB portfolios is 0.5% (see [4], page 31). This impact can be mainly attributed to the introduction of new (sub) asset classes with higher risk weights on average. The largest increases are expected for ‘equities’, ‘equity investment in funds’ and ‘subordinated debt and capital instruments other than equity’. Under adverse scenarios the impact of more granular risk weights may be magnified due to a larger share of exposures having lower credit ratings. This may result in additional impact on RWA.

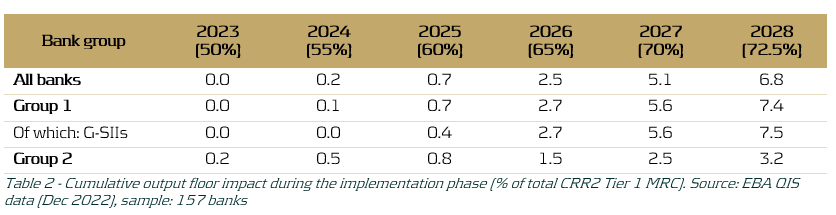

The revised SA results in more risk-sensitive capital requirements predictions over the forecast horizon due to the more granular risk weights and newly introduced asset classes. This in turn allows banks to more clearly identify their risk profile and provides the EBA with a better overview of the performance of the banking sector as a whole under adverse economic conditions. Additionally, the impact on RWA caused by the gradual increase of the output floor, as shown in Table 1, was estimated. As shown in Table 2, it was found that the gradual elevation of the output floor increasingly affects the MRC throughout the phase-in period (2023-2028).

Table 2 demonstrates that the impact is minimal in the first three years of the phase-in period, but grows significantly in the last three years of the phase-in period, with an average estimated 7.5% increase in Tier 1 MRC for G-SIIs in 2028. The larger increase in Tier 1 MRC for Group 1 banks, and G-SIIs in particular, as compared to Group 2 banks may be explained by the fact that larger banks more often employ an IRB approach and are thus more heavily impacted by an increased IRB floor, relative to their smaller counterparts. The expected impact on Group 1 banks is especially interesting in the context of the EU-wide stress test, since for the regulatory stress test only the 68 largest banks in Europe participate. Assuming that banks need to employ an increasing version of the output floor for their projections during the 2025 EU-wide stress test, this could lead to significant increases in capital requirements in the last years of the forecast horizon of the RWA projections. These increases may not be fully attributed to the adverse effects of the provided macroeconomic scenarios.

Conversely, it is good to note that a transition cap has been introduced by the Basel III reforms and adopted in CRR3. This cap puts a limit on the incremental increase of the output floor impact on total RWAs. The transitional period cap is set at 25% of a bank’s year-to-year increase in RWAs and may be exercised at the discretion of supervisors on a national level (see [5]). As a consequence, this may limit the observed increase in RWA during the execution of the 2025 EU-wide stress test.

In conclusion, the implementation of CRR3 and its adoption into the 2025 EU-wide stress test methodology may have a significant impact on the stress test results, mainly due to the gradual increase in the IRB output floor but also because of changes in the SA and IRB approaches. However, this effect may be partly mitigated by the transitional 25% cap on year-on-year incremental RWA due to the output floor increase. Additionally, the 2025 EU-wide stress test will provide a comprehensive view of the impact of CRR3, including the closer alignment between the SA and the IRB approaches, on the development of capital requirements in the banking sector under adverse conditions.

References:

- final_report_on_amendments_to_the_its_on_supervisory_reporting-crr3_crd6.pdf (europa.eu)

- The EBA starts dialogue with the banking industry on 2025 EU-Wide stress test methodology | European Banking Authority (europa.eu)

- 2025 EU-wide stress test - Methodological Note.pdf (europa.eu)

- Basel III monitoring report as of December 2022.pdf (europa.eu)

- Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms (bis.org)

- This includes the addition of the ‘Subordinated debt exposures’ asset class, as well as an additional branch of specialized lending exposures within the corporates asset class. Furthermore, a more detailed breakdown of exposures secured by mortgages on immovable property and acquisition, development and construction financing? has been introduced. ↩︎

- For in detailed information on the added asset classes and limited application of IRB refer to paragraph 25 of the report in [1]. ↩︎

- Tier 1 capital refers to the core capital held in a bank's reserves. It includes high-quality capital, predominantly in the form of shares and retained earnings that can absorb losses. The Tier 1 MRC is the minimum capital required to satisfy the regulatory Tier 1 capital ratio (ratio of a bank's core capital to its total RWA) determined by Basel and is an important metric the EBA uses to measure a bank’s health. ↩︎