PRA regulation changes in PS9/24

The PRA’s near-final Rulebook PS9/24 introduces critical updates to credit risk regulations, balancing Basel 3.1 alignment with industry competitiveness, and Zanders offers expert support to navigate these changes efficiently.

The near-final PRA Rulebook PS9/24 published on 12 September 2024 includes substantial changes in credit risk regulation compared to the Consultation Paper CP16/22. While these amendments enhance clarity of Basel 3.1 implementation, institutions should conduct in-depth impact analysis to efficiently manage capital requirement.

PRA has published draft proposal CP16/22 aligning closely with Basel 3.1 reforms. In response to industry feedback, the PRA has made material adjustments in PS9/24, which are aimed at better balancing alignment with international standards and maintaining the competitiveness of UK regulated institutions.

Key takeaways

1- Scope for a ‘Backstop’ revaluation every 5-years for valuation of real estate exposures

2- SME and Infrastructure support factor is maintained, yet firm-specific adjustments will be introduced in pillar 2A.

3- Despite industry concern on international competitiveness, the risk-sensitive approach for unrated corporate exposure is maintained.

The implementation timeline is extended to 1 January 2026 with a 4-year transitional period, which is a one-year delay from the proposed implementation date of 1 January 2025 from CP16/22.

Real Estate Exposures

According to the final regulations, the risk weights associated with regulatory real estate exposure will be calculated based on the type of property, the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, and whether the repayments rely significantly on the cash flows produced by the property. In place of the potentially complex analysis proposed in CP16/22, the rules for determining whether a real estate exposure is materially dependent on cash flows have been significantly simplified and there is now a straightforward requirement for the classification of real estate exposures.

One major change in the proposals relates to loans that are secured by commercial properties. The PRA has dropped the 100% risk weight floor for exposures backed by commercial real estate (CRE), provided that the repayment is not 'materially dependent on cash flows from the property' and that the exposure fits the 'regulatory real estate (RRE)' definition. Consequently, under the new rules, firms may, in some instances, benefit from low risk weights for commercial real estate, depending on the loan's loan-to-value (LTV) ratio and the type of counterparty involved.

Additionally, the final rules regarding the revaluation of real estate have become more risk-sensitive. Although firms are still required to use the original valuation to calculate LTV, there is now a provision allowing for a ‘Backstop’ revaluation after five years. Going forward, the PRA has eliminated the need for firms to adjust valuations to reflect the 'prudent value' sustainable throughout the loan's duration. The requirements for downward revaluation have been simplified, mandating firms to reevaluate properties when they estimate a market value decline of over 10%. Furthermore, the PRA has specified that valuations can be conducted using a robust statistical model, such as an automated valuation model (AVM).

SME support factor

The PRA has maintained the draft proposal to remove the SME support factor under SA and IRB (Pillar 1), but has applied a firm-specific structural adjustment to Pillar 2A (the ‘SME lending adjustment’). The ‘SME lending adjustment’ aims to absorb the impact of removing the SME support factor in overall capital requirement.

The PRA plans to communicate the adjusted Pillar 2 requirements to firms, ahead of the implementation date of the Basel 3.1 standards on 1 January 2026 (‘day 1’), so that firm-specific requirements will be updated at the same time as the Basel 3.1 standards are implemented.

Infrastructure support factor

The PRA has maintained the draft proposal to remove infrastructure support factor under SA and IRB approach, but has made two material changes which will diminish the impact on overall capital requirement.

i. apply a firm-specific structural adjustment to Pillar 2A (the ‘SME lending adjustment’), which will minimize disruption in overall capital requirement.

ii. introduce a new substantially stronger category in the slotting approach for IRB. PRA proposed lower risk-weight on the ‘substantially stronger’ IPRE exposures in CP16/22. The new definition of ‘substantially stronger’ is expected to include broader scope of IPRE exposures, thus lowering overall capital requirement.

Unrated corporate exposures

The PRA has maintained the draft proposal of introducing a two-way method on unrated corporate exposures: risk-sensitive and risk-neutral approach. Since the new approach does not apply in other jurisdictions, additional operational challenge is expected. Also, the 135% risk-weight on Non-IG(non-Investment Grade) unrated corporate exposure is higher than 100% in other jurisdictions, implying higher lending cost for UK regulated banks compared to its internationally regulated peers.

i. risk-sensitive approach : The PRA has proposed a risk-sensitive approach additional to the Basel III reforms. Exposures assessed by firms as IG would be risk-weighted at 65%, while exposures assessed by firms as Non-IG would be risk-weighted at 135%. This is a more risk-sensitive approach which aims to maintain an aggregate level of RWAs broadly consistent with the Basel III reforms.

ii. risk-neutral approach: 100% risk weight is applied where the risk-sensitive approach is too costly or complex.

In conclusion, the PRA's near-final Rulebook (PS9/24) reflects significant revisions to credit risk regulation that enhance clarity and alignment with Basel 3.1, while addressing industry feedback. The introduction of a five-year 'backstop' revaluation for real estate exposures, firm-specific adjustments for SMEs and infrastructure support factors, and the maintenance of a risk-sensitive approach for unrated corporate exposures underscore the PRA's commitment to balancing regulatory requirements with maintaining the competitiveness of UK institutions.

The extended implementation timeline to 1 January 2026, along with the transitional period, allows firms adequate time for adjustment. Overall, these changes aim to foster a more robust and competitive banking environment, while also navigating the complexities introduced by differing international standards.

How can Zanders help?

We have extensive experience of implementation and validation of Pillar 1 & 2 models which allows us to effectively support our Clients managing the change process to full compliance with the latest regulations.

From our experience, as the following are key areas on which our services can add most value:

1- Carry out thorough self-assessment against new requirements including an impact analyses of new regulations on their capital requirements.

2- Support model development activities to align models to new rules; we could be done either on an advisory basis or via direct supply of additional resources

3- Support amendments to Pillar 2 models (which will have to reflect changes to Pillar 1 models)

4- Support Internal Validation activities across Pillar 1 & 2

5- Carry out quality assurance on final models & documentation before final submission to the PRA

6- Support adoption of solutions for prudential valuation of (real estate) collateral while integrating climate risk information.

Please reach out to Paolo Vareschi or Suneet Dutta Roy to find out more about how we could support you on your journey to Basel 3.1 compliance.

References

[1] Bank of England (2024), PS9/24 – Implementation of the Basel 3.1 standards near-final part 2 URL PS9/24

[2] Bank of England (2022), CP16/22 – Implementation of the Basel 3.1 standards

URL CP16/22

Redefining Credit Portfolio Strategies: Balancing Risk & Reward in a Volatile Economy

This article delves into a three-step approach to portfolio optimization by harnessing the power of advanced data analytics and state-of-the-art quantitative models and tools.

In today's dynamic economic landscape, optimizing portfolio composition to fortify against challenges such as inflation, slower growth, and geopolitical tensions is ever more paramount. These factors can significantly influence consumer behavior and impact loan performance. Navigating this uncertain environment demands banks adeptly strike a delicate balance between managing credit risk and profitability.

Why does managing your risk reward matter?

Quantitative techniques are an essential tool to effectively optimize your portfolio’s risk reward profile, as this aspect is often based on inefficient approaches.

Existing models and procedures across the credit lifecycle, especially those relating to loan origination and account management, may not be optimized to accommodate current macro-economic challenges.

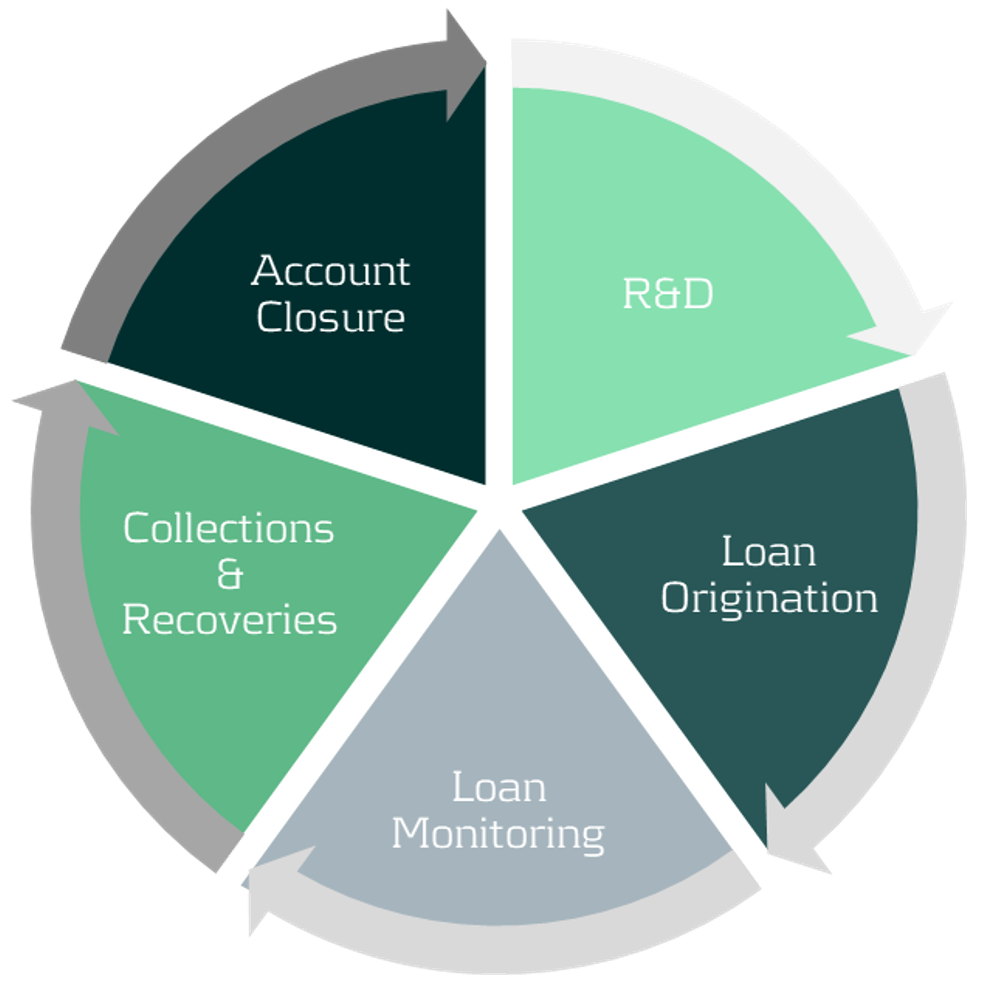

Figure 1: Credit lifecycle.

Current challenges facing banks

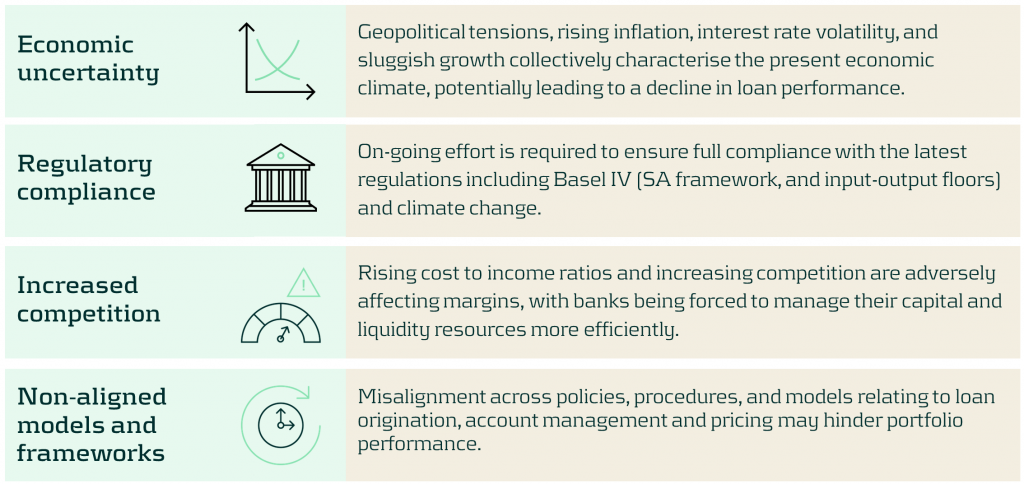

Some of the key challenges banks face when balancing credit risk and profitability include:

Our approach to optimizing your risk reward profile

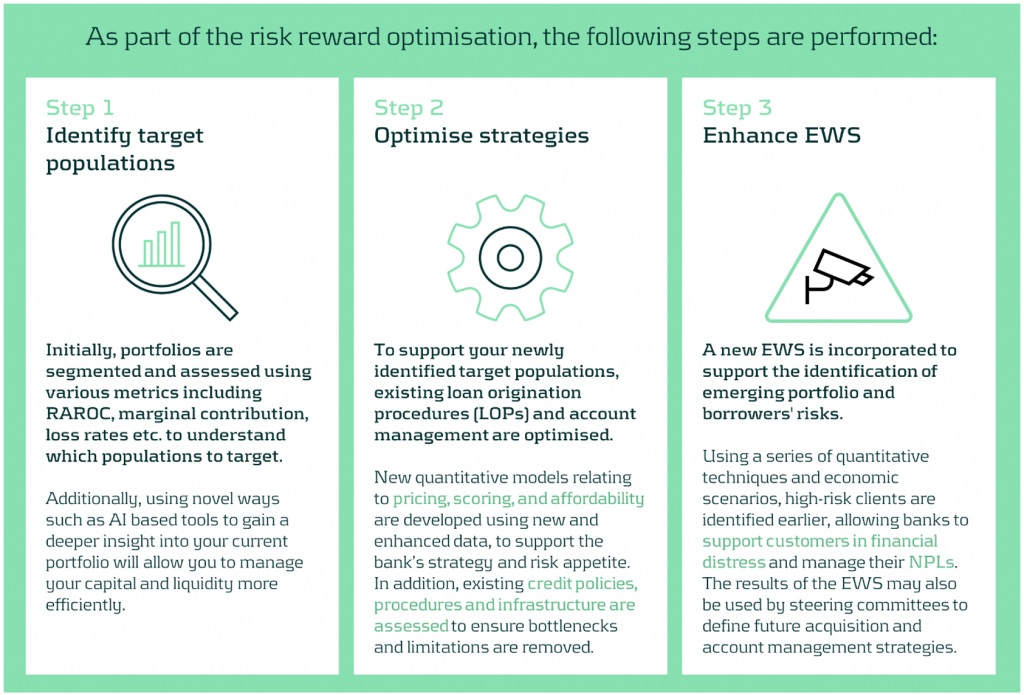

Our optimization approach consists of a holistic three step diagnosis of your current practices, to support your strategy and encourage alignment across business units and processes.

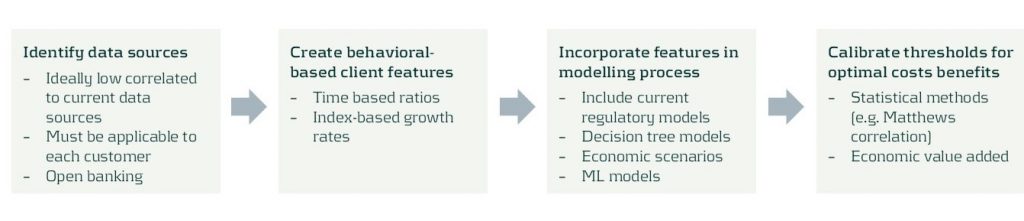

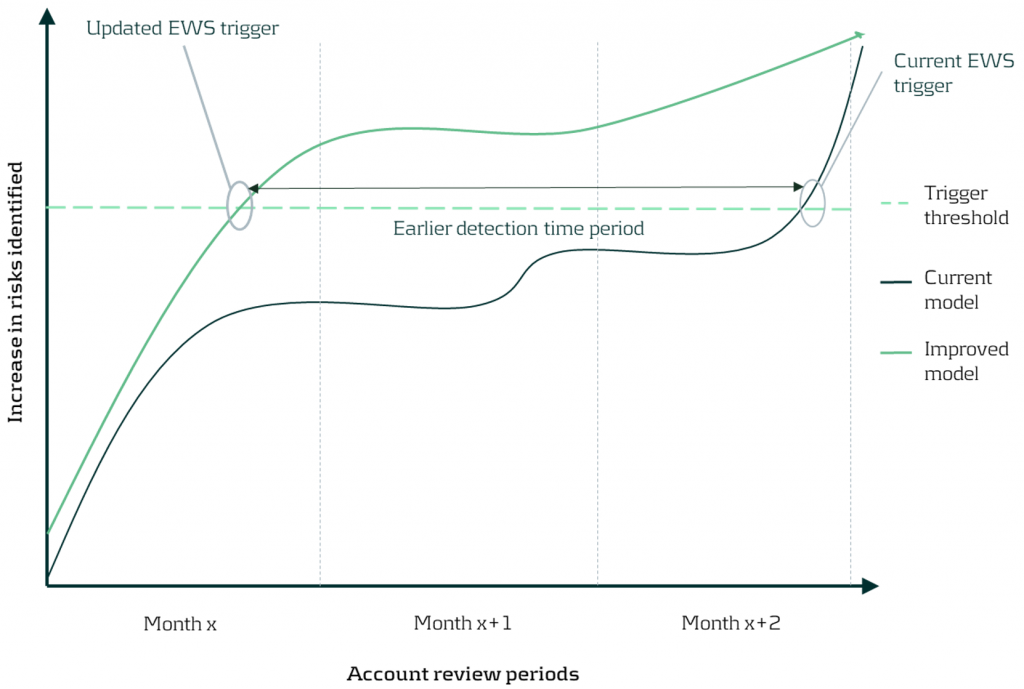

The initial step of the process involves understanding your current portfolio(s) by using a variety of segmentation methodologies and metrics. The second step implements the necessary changes once your primary target populations have been identified. This may include reassessing your models and strategies across the loan origination and account management processes. Finally, a new state-of-the-art Early Warning System (EWS) can be deployed to identify emerging risks and take pro-active action where necessary.

A closer look at redefining your target populations

With the proliferation of advanced data analytics, banks are now better positioned to identify profitable, low-risk segments. Machine Learning (ML) methodologies such as k-means clustering, neural networks, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) enable effective customer grouping, behavior forecasting, and market sentiment analysis.

Risk-based pricing remains critical for acquisition strategies, assessing segment sensitivity to different pricing strategies, to maximize revenue and reduce credit losses.

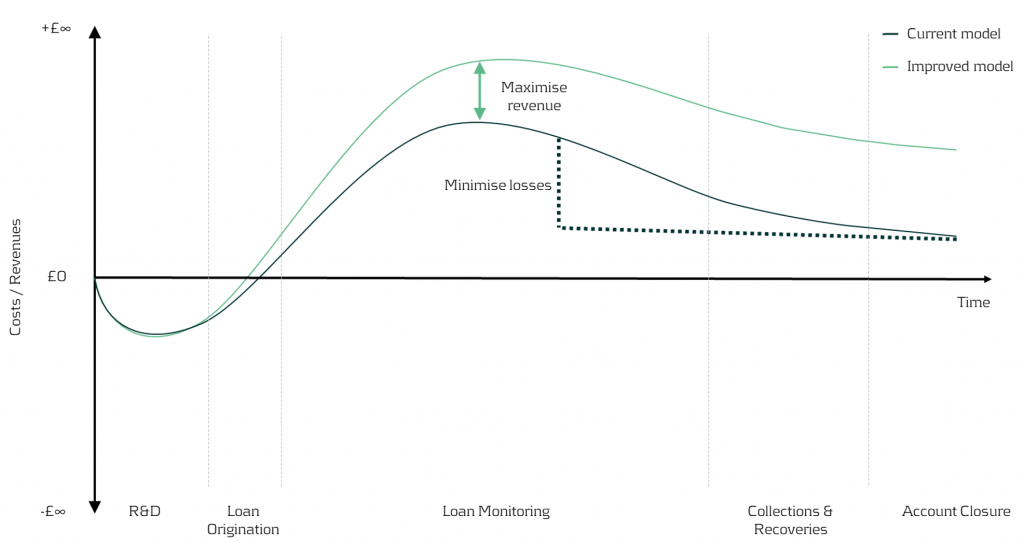

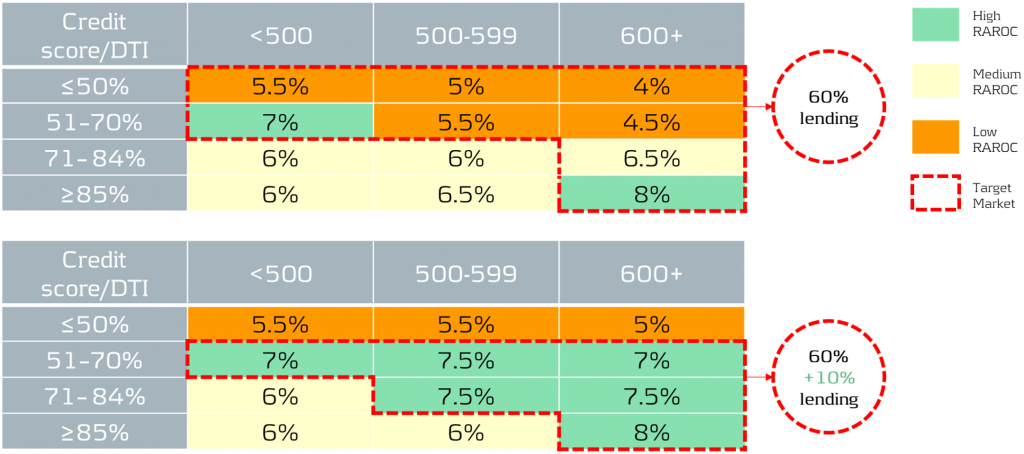

Figure 2: In the illustration above, we can visually see the impact on earnings throughout the credit lifecycle driven by redefining the target populations and application of different pricing strategies.

In our simplified example, based on the RAROC metric applied to an unsecured loans portfolio, we take a 2-step approach:

1- Identify target populations by comparing RAROC across different combinations of credit scores and debt-to-income (DTI) ratios. This helps identify the most capital efficient segments to target.

2- Assess the sensitivity of RAROC to different pricing strategies to find the optimal price points to maximize profit over a select period - in this scenario we use a 5-year time horizon.

Figure 3: The top table showcases the current portfolio mix and performance, while the bottom table illustrates the effects of adjusting the pricing and acquisition strategy. By redefining the target populations and changing the pricing strategy, it is possible to reallocate capital to the most profitable segments whilst maintaining within credit risk appetite. For example, 60% of current lending is towards a mix of low to high RAROC segments, but under the new proposed strategy, 70% of total capital is allocated to the highest RAROC segments.

Uncovering risks and seizing opportunities

The current state of Early Warning Systems

Many organizations rely on regulatory models and standard risk triggers (e.g., no. of customers 30 day past due, NPL ratio etc.) to set their EWS thresholds. Whilst this may be a good starting point, traditional models and tools often miss timely deteriorations and valuable opportunities, as they typically use limited and/or outdated data features.

Target state of Early Warning Systems

Leveraging timely and relevant data, combined with next-generation AI and machine learning techniques, enables early identification of customer deterioration, resulting in prompt intervention and significantly lower impairment costs and NPL ratios.

Furthermore, an effective EWS framework empowers your organization to spot new growth areas, capitalize on cross-selling opportunities, and enhance existing strategies, driving significant benefits to your P&L.

Figure 4: By updating the early warning triggers using new timely data and advanced techniques, detection of customer deterioration can be greatly improved enabling firms to proactively support clients and enhance the firm’s financial position.

Discover the benefits of optimizing your portfolios

Discover the benefits in optimizing your portfolios’ risk-reward profile using our comprehensive approach as we turn today’s challenges into tomorrow’s advantages. Such benefits include:

Conclusion

In today's rapidly evolving market, the need for sophisticated credit risk portfolio management is ever more critical. With our comprehensive approach, banks are empowered to not merely weather economic uncertainties, but to thrive within them by striking the optimal risk-reward balance. Through leveraging advanced data analytics and deploying quantitative tools and models, we help institutions strategically position themselves for sustainable growth, and comply with increasing regulatory demands especially with the advent of Basel IV. Contact us to turn today’s challenges into tomorrow’s opportunities.

For more information on this topic, contact Martijn de Groot (Partner) or Paolo Vareschi (Director).

The Benefits of Exposure Attribution in Counterparty Credit Risk

In an increasingly complex regulatory landscape, effective management of counterparty credit risk is crucial for maintaining financial stability and regulatory compliance.

Accurately attributing changes in counterparty credit exposures is essential for understanding risk profiles and making informed decisions. However, traditional approaches for exposure attribution often pose significant challenges, including labor-intensive manual processes, calculation uncertainties, and incomplete analyses.

In this article, we discuss the issues with existing exposure attribution techniques and explore Zanders’ automated approach, which reduces workloads and enhances the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the attribution.

Our approach to attributing changes in counterparty credit exposures

The attribution of daily exposure changes in counterparty credit risk often presents challenges that strain the resources of credit risk managers and quantitative analysts. To tackle this issue, Zanders has developed an attribution methodology that efficiently automates the attribution process, improving the efficiency, reactivity and coverage of exposure attribution.

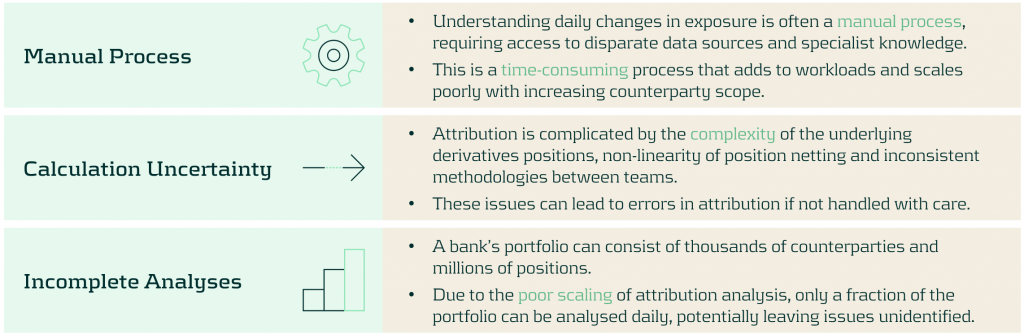

Challenges in Exposure Attribution

Credit risk managers monitor the evolution of exposures over time to manage counterparty credit risk exposures against the bank’s risk appetite and limits. This frequently requires rapid analysis to attribute the changes to exposures, which presents several challenges:

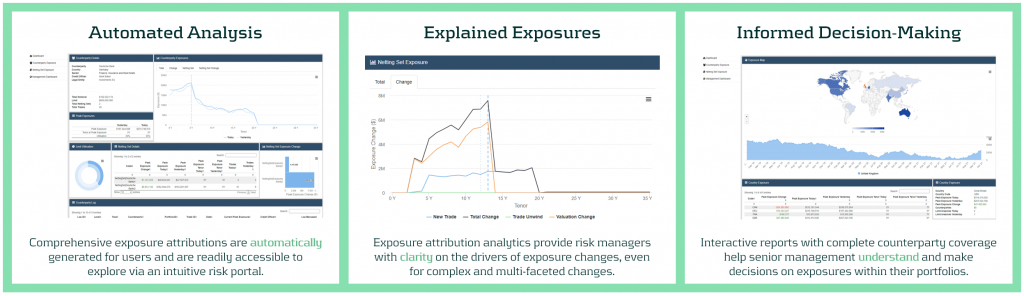

Zanders’ approach: an automated approach to exposure attribution

Our methodology resolves these problems with an analytics layer that interfaces with the risk engine to accelerate and automate the daily exposure attribution process. The results can also be accessed and explored via an interactive web portal, providing risk managers and senior management with the tools they need to rapidly analyze and understand their risk.

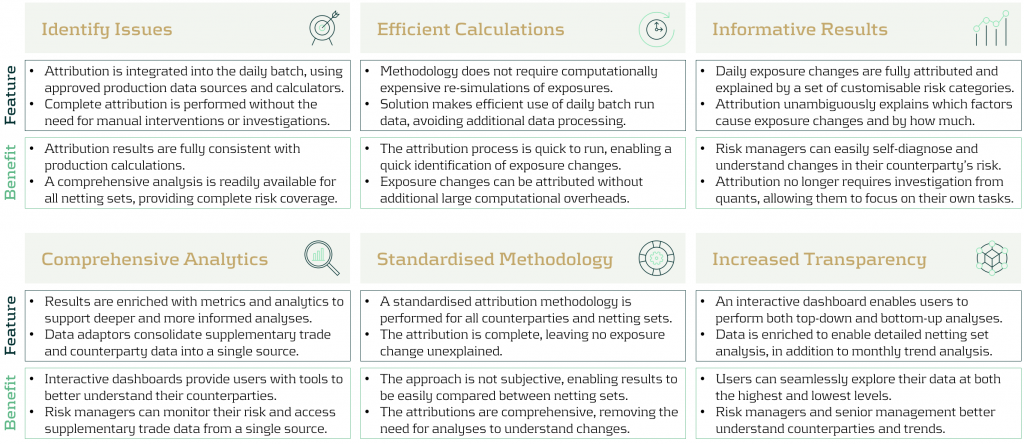

Key features and benefits of our approach

Zanders’ approach provides multiple improvements to the exposure attribution process. This reduces the workloads of key risk teams and increases risk coverage without additional overheads. Below, we describe the benefits of each of the main features of our approach.

Zanders Recommends

An automated attribution of exposures empowers banks teams to better understand and handle their counterparty credit risk. To make the best use of automated attribution techniques, Zanders recommends that banks:

- Increase risk scope: The increased efficiency of attribution should be used to provide a more comprehensive and granular coverage of the exposures of counterparties, sectors and regions.

- Reduce quant utilization: Risk managers should use automated dashboards and analytics to perform their own exposure investigations, reducing the workload of quantitative risk teams.

- Augment decision making: Risk managers should utilize dashboards and analytics to ensure they make more timely and informed decisions.

- Proactive monitoring: Automated reports and monitoring should be reviewed regularly to ensure risks are tackled in a proactive manner.

- Increase information transfer: Dashboards should be made available across teams to ensure that information is shared in a transparent, consistent and more timely manner.

Conclusion

The effective management of counterparty credit risk is a critical task for banks and financial institutions. However, the traditional approach of manual exposure attribution often results in inefficient processes, calculation uncertainties, and incomplete analyses. Zanders' innovative methodology for automating exposure attribution offers a comprehensive solution to these challenges and provides banks with a robust framework to navigate the complexities of exposure attribution. The approach is highly effective at improving the speed, coverage, and accuracy of exposure attribution, supporting risk managers and senior management to make informed and timely decisions.

For more information about how Zanders can support you with exposure attribution, please contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Mark Baber (Senior Manager).

Converging on resilience: Integrating CCR, XVA, and real-time risk management

In a world where the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) commands much attention, it’s easy for counterparty credit risk (CCR) to slip under the radar.

However, CCR remains an essential element in banking risk management, particularly as it converges with valuation adjustments. These changes reflect growing regulatory expectations, which were further amplified by recent cases such as Archegos. Furthermore, regulatory focus seems to be shifting, particularly in the U.S., away from the Internal Model Method (IMM) and toward standardised approaches. This article provides strategic insights for senior executives navigating the evolving CCR framework and its regulatory landscape.

Evolving trends in CCR and XVA

Counterparty credit risk (CCR) has evolved significantly, with banks now adopting a closely integrated approach with valuation adjustments (XVA) — particularly Credit Valuation Adjustment (CVA), Funding Valuation Adjustment (FVA), and Capital Valuation Adjustment (KVA) — to fully account for risk and costs in trade pricing. This trend towards blending XVA into CCR has been driven by the desire for more accurate pricing and capital decisions that reflect the true risk profile of the underlying instruments/ positions.

In addition, recent years have seen a marked increase in the use of collateral and initial margin as mitigants for CCR. While this approach is essential for managing credit exposures, it simultaneously shifts a portion of the risk profile into contingent market and liquidity risks, which, in turn, introduces requirements for real-time monitoring and enhanced data capabilities to capture both the credit and liquidity dimensions of CCR. Ultimately, this introduces additional risks and modelling challenges with respect to wrong way risk and clearing counterparty risk.

As banks continue to invest in advanced XVA models and supporting technologies, senior executives must ensure that systems are equipped to adapt to these new risk characteristics, as well as to meet growing regulatory scrutiny around collateral management and liquidity resilience.

The Internal Model Method (IMM) vs. SA-CCR

In terms of calculating CCR, approaches based on IMM and SA-CCR provide divergent paths. On one hand, IMM allows banks to tailor models to specific risks, potentially leading to capital efficiencies. SA-CCR, on the other hand, offers a standardised approach that’s straightforward yet conservative. Regulatory trends indicate a shift toward SA-CCR, especially in the U.S., where reliance on IMM is diminishing.

As banks shift towards SA-CCR for Regulatory capital and IMM is used increasingly for internal purposes, senior leaders might need to re-evaluate whether separate calibrations for CVA and IMM are warranted or if CVA data can inform IMM processes as well.

Regulatory focus on CCR: Real-time monitoring, stress testing, and resilience

Real-time monitoring and stress testing are taking centre stage following increased regulatory focus on resilience. Evolving guidelines, such as those from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), emphasise a need for efficiency and convergence between trading and risk management systems. This means that banks must incorporate real-time risk data and dynamic monitoring to proactively manage CCR exposures and respond to changes in a timely manner.

CVA hedging and regulatory treatment under IMM

CVA hedging aims to mitigate counterparty credit spread volatility, which affects portfolio credit risk. However, current regulations limit offsetting CVA hedges against CCR exposures under IMM. This regulatory separation of capital for CVA and CCR leads to some inefficiencies, as institutions can’t fully leverage hedges to reduce overall exposure.

Ongoing BIS discussions suggest potential reforms for recognising CVA hedges within CCR frameworks, offering a chance for more dynamic risk management. Additionally, banks are exploring CCR capital management through LGD reductions using third-party financial guarantees, potentially allowing for more efficient capital use. For executives, tracking these regulatory developments could reveal opportunities for more comprehensive and capital-efficient approaches to CCR.

Leveraging advanced analytics and data integration for CCR

Emerging technologies in data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and scenario analysis are revolutionising CCR. Real-time data analytics provide insights into counterparty exposures but typically come at significant computational costs: high-performance computing can help mitigate this, and, if coupled with AI, enable predictive modelling and early warning systems. For senior leaders, integrating data from risk, finance, and treasury can optimise CCR insights and streamline decision-making, making risk management more responsive and aligned with compliance.

By leveraging advanced analytics, banks can respond proactively to potential CCR threats, particularly in scenarios where early intervention is critical. These technologies equip executives with the tools to not only mitigate CCR but also enhance overall risk and capital management strategies.

Strategic considerations for senior executives: Capital efficiency and resilience

Balancing capital efficiency with resilience requires careful alignment of CCR and XVA frameworks with governance and strategy. To meet both regulatory requirements and competitive pressures, executives should foster collaboration across risk, finance, and treasury functions. This alignment will enhance capital allocation, pricing strategies, and overall governance structures.

For banks facing capital constraints, third-party optimisation can be a viable strategy to manage the demands of SA-CCR. Executives should also consider refining data integration and analytics capabilities to support efficient, resilient risk management that is adaptable to regulatory shifts.

Conclusion

As counterparty credit risk re-emerges as a focal point for financial institutions, its integration with XVA, and the shifting emphasis from IMM to SA-CCR, underscore the need for proactive CCR management. For senior risk executives, adapting to this complex landscape requires striking a balance between resilience and efficiency. Embracing real-time monitoring, advanced analytics, and strategic cross-functional collaboration is crucial to building CCR frameworks that withstand regulatory scrutiny and position banks competitively.

In a financial landscape that is increasingly interconnected and volatile, an agile and resilient approach to CCR will serve as a foundation for long-term stability. At Zanders, we have significant experience implementing advanced analytics for CCR. By investing in robust CCR frameworks and staying attuned to evolving regulatory expectations, senior executives can prepare their institutions for the future of CCR and beyond thereby avoiding being left behind.

Confirmed Methodology for Credit Risk in EBA 2025 Stress Test

On November 12 2024, the confirmed methodology for the EBA 2025 stress testing exercise was published on the EBA website. This is the final version of the draft for initial consultation that was published earlier.

| The timelines for the entire exercise have been extended to accommodate the changes in scope: | |

| Launch of exercise (macro scenarios) | Second half of January 2025 |

| First submission of results to the EBA | End of April 2025 |

| Second submission to the EBA | Early June 2025 |

| Final submission to the EBA | Early July 2025 |

| Publication of results | Beginning of August 2025 |

Below we share the most significant aspects for Credit Risk and related challenges. In the coming weeks we will share separate articles to cover areas related to Market Risk, Net Interest Income & Expenses and Operational Risk.

The final methodology, along with the requirements introduced by the CRR3 poses significant challenges on the execution of the Credit Risk stress testing. Earlier we provided details on this topic and possible impacts on stress testing results, see our article: “Implications of CRR3 for the 2025 EU-wide stress test” Regarding the EBA 2025 stress test we view the following 5 points as key areas of concern:

1- The EBA stress test requires different starting points; actual and restated CRR3 figures. This raises requirements in data management, reporting and implementation of related processes.

2- The EBA stress test requires banks to report both transitional and fully loaded results under CRR3; this requires the execution of additional calculations and implementation of supporting data processes.

3- The changes in classification of assets require targeted effort on the modelling side, stress test approach and related data structures.

4- Implementation of the Standardized Approach output floor as part of the stress test logic.

5- Additional effort is needed to correctly align Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 models, in terms of development, implementation and validation.

At Zanders, we specialize in risk advisory and our consultants have participated in every single EU wide stress testing exercise, as well as a few others going back to the initial stress tests in 2009 following the Great Financial Crisis. We can support you throughout all key stages of the stress testing exercise across all areas to ensure a successful submission of the final templates.

Based on the expertise in Stress Testing we have gained over the last 15 years, our clients benefit the most from our services in these areas:

- Full gap analysis against latest set of requirements

- Review, design and implementation of data processes & relevant data quality controls

- Alignment of Pillar 2 models to Pillar 1 (including CCR3 requirements)

- Design, implementation and execution of stress testing models

- Full automation of populating EBA templates including reconciliation and data quality checks.

Contact us for more information about how we can help make this your most successful run yet. Reach out to Martijn de Groot, Partner at Zanders.

Basel IV and External Credit Ratings

Explore how Basel IV reforms and enhanced due diligence requirements will transform regulatory capital assessments for credit risk, fostering a more resilient and informed financial sector.

The Basel IV reforms, which are set to be implemented on 1 January 2025 via amendments to the EU Capital Requirement Regulation, have introduced changes to the Standardized Approach for credit risk (SA-CR). The Basel framework is implemented in the European Union mainly through the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR3) and Capital Requirements Directive (CRD6). The CRR3 changes are designed to address shortcomings in the existing prudential standards, by among other items, introducing a framework with greater risk sensitivity and reducing the reliance on external ratings. Action by banks is required to remain compliant with the CRR. Overall, the share of RWEA derived through an external credit rating in the EU-27 remains limited, representing less than 10% of the total RWEA under the SA with the CRR.

Introduction

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) identified the excessive dependence on external credit ratings as a flaw within the Standardised Approach (SA), observing that firms frequently used these ratings to compute Risk-Weighted Assets (RWAs) without adequately understanding the associated risks of their exposures. To address this issue, regulators have implemented changes aimed to reduce the mechanical reliance on external credit ratings and to encourage firms to use external credit ratings in a more informed manner. The objective is to diminish the chances of underestimating financial risks in order to further build a more resilient financial industry. Overall, the share of Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) derived through an external credit rating remains limited, and in Europe it represents less than 10% of the total RWA under the SA.

The concept of due diligence is pivotal in the regulatory framework. It refers to the rigorous process financial institutions are expected to undertake to understand and assess the risks associated with their exposures fully. Regulators promote due diligence to ensure that banks do not solely rely on external assessments, such as credit ratings, but instead conduct their own comprehensive analysis.

The due diligence is a process performed by banks with the aim of understanding the risk profile and characteristics of their counterparties at origination and thereafter on a regular basis (at least annually). This includes assessing the appropriateness of risk weights, especially when using external ratings. The level of due diligence should match the size and complexity of the bank's activities. Banks must evaluate the operating and financial performance of counterparties, using internal credit analysis or third-party analytics as necessary, and regularly access counterparty information. Climate-related financial risks should also be considered, and due diligence must be conducted both at the solo entity level and consolidated level.

Banks must establish effective internal policies, processes, systems, and controls to ensure correct risk weight assignment to counterparties. They should be able to prove to supervisors that their due diligence is appropriate. Supervisors are responsible for reviewing these analyses and taking action if due diligence is not properly performed.

Banks should have methodologies to assess credit risk for individual borrowers and at the portfolio level, considering both rated and unrated exposures. They must ensure that risk weights under the Standardised Approach reflect the inherent risk. If a bank identifies that an exposure, especially an unrated one, has higher inherent risk than implied by its assigned risk weight, it should factor this higher risk into its overall capital adequacy evaluation.

Banks need to ensure they have an adequate understanding of their counterparties’ risk profiles and characteristics. The diligent monitoring of counterparties is applicable to all exposures under the SA. Banks would need to take reasonable and adequate steps to assess the operating and financial condition of each counterparty.

Rating System

The external credit assessment institutions (ECAIs) are credit rating agencies recognised by National supervisors. The External Credit ECAIs play a significant role in the SA through the mapping of each of their credit assessments to the corresponding risk weights. Supervisors will be responsible for assigning an eligible ECAI’s credit risk assessments to the risk weights available under the SA. The mapping of credit assessments should reflect the long-term default rate.

Exposures to banks, exposures to securities firms and other financial institutions and exposures to corporates will be risk-weighted based on the following hierarchy External Credit Risk Assessment Approach (ECRA) and the Standardised Credit Risk Assessment Approach (SCRA).

ECRA: Used in jurisdictions allowing external ratings. If an external rating is from an unrecognized or non-nominated ECAI, the exposure is considered unrated. Also, banks must perform due diligence to ensure ratings reflect counterparty creditworthiness and assign higher risk weights if due diligence reveals greater risk than the rating suggests.

SCRA: Used where external ratings are not allowed. Applies to all bank exposures in these jurisdictions and unrated exposures in jurisdictions allowing external ratings. Banks classify exposures into three grades:

- Grade A: Adequate capacity to meet obligations in a timely manner.

- Grade B: Substantial credit risk, such as repayment capacities that are dependent on stable or favourable economic or business conditions.

- Grade C: Higher credit risk, where the counterparty has material default risks and limited margins of safety

The CRR Final Agreement includes a new article (Article 495e) that allows competent authorities to permit institutions to use an ECAI credit assessment assuming implicit government support until December 31, 2029, despite the provisions of Article 138, point (g).

In cases where external credit ratings are used for risk-weighting purposes, due diligence should be used to assess whether the risk weight applied is appropriate and prudent.

If the due diligence assessment suggests an exposure has higher risk characteristics than implied by the risk weight assigned to the relevant Credit Quality Step (CQS) of an exposure, the bank would assign the risk weight at least one higher than the CQS indicated by the counterparty’s external credit rating.

Criticisms to this approach are:

- Banks are mandated to use nominated ECAI ratings consistently for all exposures in an asset class, requiring banks to carry out a due diligence on each and every ECAI rating goes against the principle of consistent use of these ratings.

- When banks apply the output floor, ECAI ratings act as a backstop to internal ratings. In case the due diligence would imply the need to assign a high-risk weight, the output floor could no longer be used consistently across banks to compare capital requirements.

Implementation Challenges

The regulation requires the bank to conduct due diligence to ensure a comprehensive understanding, both at origination and on a regular basis (at least annually), of the risk profile and characteristics of their counterparties. The challenges associated with implementing this regulation can be grouped into three primary categories: governance, business processes, and systems & data.

Governance

The existing governance framework must be enhanced to reflect the new responsibilities imposed by the regulation. This involves integrating the due diligence requirements into the overall governance structure, ensuring that accountability and oversight mechanisms are clearly defined. Additionally, it is crucial to establish clear lines of communication and decision-making processes to manage the new regulatory obligations effectively.

Business Process

A new business process for conducting due diligence must be designed and implemented, tailored to the size and complexity of the exposures. This process should address gaps in existing internal thresholds, controls, and policies. It is essential to establish comprehensive procedures that cover the identification, assessment, and monitoring of counterparties' risk profiles. This includes setting clear criteria for due diligence, defining roles and responsibilities, and ensuring that all relevant staff are adequately trained.

Systems & Data

The implementation of the regulation requires access to accurate and comprehensive data necessary for the rating system. Challenges may arise from missing or unavailable data, which are critical for assessing counterparties' risk profiles. Furthermore, reliance on manual solutions may not be feasible given the complexity and volume of data required. Therefore, it is imperative to develop robust data management systems that can capture, store, and analyse the necessary information efficiently. This may involve investing in new technology and infrastructure to automate data collection and analysis processes, ensuring data integrity and consistency.

Overall, addressing these implementation challenges requires a coordinated effort across the organization, with a focus on enhancing governance frameworks, developing comprehensive business processes, and investing in advanced systems and data management solutions.

How can Zanders help?

As a trusted advisor, we built a track record of implementing CRR3 throughout a heterogeneous group of financial institutions. This provides us with an overview of how different entities in the industry deal with the different implementation challenges presented above.

Zanders has been engaged to provide project management for these Basel IV implementation projects. By leveraging the expertise of Zanders' subject matter experts, we ensure an efficient and insightful gap analysis tailored to your bank's specific needs. Based on this analysis, combined with our extensive experience, we deliver customized strategic advice to our clients, impacting multiple departments within the bank. Furthermore, as an independent advisor, we always strive to challenge the status quo and align all stakeholders effectively.

In-depth Portfolio Analysis: Our initial step involves conducting a thorough portfolio scan to identify exposures to both currently unrated institutions and those that rely solely on government ratings. This analysis will help in understanding the extent of the challenge and planning the necessary adjustments in your credit risk framework.

Development of Tailored Models: Drawing from our extensive experience and industry benchmarks, Zanders will collaborate with your project team to devise a range of potential solutions. Each solution will be detailed with a clear overview of the required time, effort, potential impact on Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA), and the specific steps needed for implementation. Our approach will ensure that you have all the necessary information to make informed strategic decisions.

Robust Solutions for Achieving Compliance: Our proprietary Credit Risk Suite cloud platform offers banks robust tools to independently assess and monitor the credit quality of corporate and financial exposures (externally rated or not) as well as determine the relevant ECRA and SCRA ratings.

Strategic Decision-Making Support: Zanders will support your Management Team (MT) in the decision-making process by providing expert advice and impact analysis for each proposed solution. This support aims to equip your MT with the insights needed to choose the most appropriate strategy for your institution.

Implementation Guidance: Once a decision has been made, Zanders will guide your institution through the specific actions required to implement the chosen solution effectively. Our team will provide ongoing support and ensure that the implementation is aligned with both regulatory requirements and your institution’s strategic objectives.

Continuous Adaptation and Optimization: In response to the dynamic regulatory landscape and your bank's evolving needs, Zanders remains committed to advising and adjusting strategies as needed. Whether it's through developing an internal rating methodology, imposing new lending restrictions, or reconsidering business relations with unrated institutions, we ensure that your solutions are sustainable and compliant.

Independent and Innovative Thinking: As an independent advisor, Zanders continuously challenges the status quo, pushing for innovative solutions that not only comply with regulatory demands but also enhance your competitive edge. Our independent stance ensures that our advice is unbiased and wholly in your best interest.

By partnering with Zanders, you gain access to a team of dedicated professionals who are committed to ensuring your successful navigation through the regulatory complexities of Basel IV and CRR3. Our expertise and tailored approaches enable your institution to manage and mitigate risks efficiently while aligning with the strategic goals and operational realities of your bank. Reach out to Tim Neijs or Marco Zamboni for further comments or questions.

REFERENCE

[1] BCBS, The Basel Framework, Basel https://www.bis.org/basel_framework

[2] Regulation (EU) No 575/2013

[3] Directive 2013/36/EU

[4] EBA Roadmap on strengthening the prudential framework

[5] EBA REPORT ON RELIANCE ON EXTERNAL CREDIT RATINGS

Regulatory exemptions during extreme market stresses: EBA publishes final RTS on extraordinary circumstances for continuing the use of internal models

Covid-19 exposed flaws in banks’ risk models, prompting regulatory exemptions, while new EBA guidelines aim to identify and manage future extreme market stresses.

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered unprecedented market volatility, causing widespread failures in banks' internal risk models. These backtesting failures threatened to increase capital requirements and restrict the use of advanced models. To avoid a potentially dangerous feedback loop from the lower liquidity, regulators responded by granting temporary exemptions for certain pandemic-related model exceptions. To act faster to future crises and reduce unreasonable increases to banks’ capital requirements, more recent regulation directly comments on when and how similar exemptions may be imposed.

Although FRTB regulation briefly comments on such situations of market stress, where exemptions may be imposed for backtesting and profit and loss attribution (PLA), it provides very little explanation of how banks can prove to the regulators that such a scenario has occurred. On 28th June, the EBA published its final draft technical standards on extraordinary circumstances for continuing the use of internal models for market risk. These standards discuss the EBA’s take on these exemptions and provide some guidelines on which indicators can be used to identify periods of extreme market stresses.

Background and the BCBS

In the Basel III standards, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) briefly comment on rare occasions of cross-border financial market stress or regime shifts (hereby called extreme stresses) where, due to exceptional circumstances, banks may fail backtesting and the PLA test. In addition to backtesting overages, banks often see an increasing mismatch between Front Office and Risk P&L during periods of extreme stresses, causing trading desks to fail PLA.

The BCBS comment that one potential supervisory response could be to allow the failing desks to continue using the internal models approach (IMA), however only if the banks models are updated to adequately handle the extreme stresses. The BCBS make it clear that the regulators will only consider the most extraordinary and systemic circumstances. The regulation does not, however, give any indication of what analysis banks can provide as evidence for the extreme stresses which are causing the backtesting or PLA failures.

The EBA’s standards

The EBA’s conditions for extraordinary circumstances, based on the BCBS regulation, provide some more guidance. Similar to the BCBS, the EBA’s main conditions are that a significant cross-border financial market stress has been observed or a major regime shift has taken place. They also agree that such scenarios would lead to poor outcomes of backtesting or PLA that do not relate to deficiencies in the internal model itself.

To assess whether the above conditions have been met, the EBA will consider the following criteria:

- Analysis of volatility indices (such as the VIX and the VSTOXX), and indicators of realised volatilities, which are deemed to be appropriate to capture the extreme stresses,

- Review of the above volatility analysis to check whether they are comparable to, or more extreme than, those observed during COVID-19 or the global financial crisis,

- Assessment of the speed at which the extreme stresses took place,

- Analysis of correlations and correlation indicators, which adequately capture the extreme stresses, and whether a significant and sudden change of them occurred,

- Analysis of how statistical characteristics during the period of extreme stresses differ to those during the reference period used for the calibration of the VaR model.

The granularity of the criteria

The EBA make it clear that the standards do not provide an exhaustive list of suitable indicators to automatically trigger the recognition of the extreme stresses. This is because they believe that cases of extreme stresses are very unique and would not be able to be universally captured using a small set of prescribed indicators.

They mention that defining a very specific set of indicators would potentially lead to banks developing automated or quasi-automated triggering mechanisms for the extreme stresses. When applied to many market scenarios, this may lead to a large number of unnecessary triggers due the specificity of the prescribed indicators. As such, the EBA advise that the analysis should take a more general approach, taking into consideration the uniqueness of each extreme stress scenario.

Responses to questions

The publication also summarises responses to the original Consultation Paper EBA/CP/2023/19. The responses discuss several different indicators or factors, on top of the suggested volatility indices, that could be used to identify the extreme stresses:

- The responses highlight the importance of correlation indicators. This is because stress periods are characterised by dislocations in the market, which can show increased correlations and heightened systemic risk.

- They also mention the use of liquidity indicators. This could include jumps of the risk-free rates (RFRs) or index swap (OIS) indicators. These liquidity indicators could be used to identify regime shifts by benchmarking against situations of significant cross-border market stress (for example, a liquidity crisis).

- Unusual deviations in the markets may also be strong indicators of the extreme stresses. For example, there could be a rapid widening of spreads between emerging and developed markets triggered by regional debt crisis. Unusual deviations between cash and derivatives markets or large difference between futures/forward and spot prices could also indicate extreme stresses.

- They suggest that restrictions on trading or delivery of financial instruments/commodities may be indicative of extreme stresses. For example, the restrictions faced by the Russian ruble due to the Russia-Ukraine war.

- Finally, the responses highlighted that an unusual amount of backtesting overages, for example more than 2 in a month, could also be a useful indicator.

Zanders recommends

It’s important that banks are prepared for potential extreme stress scenarios in the future. To achieve this, we recommend the following:

- Develop a holistic set of indicators and metrics that capture signs of potential extreme stresses,

- Use early warning signals to preempt potential upcoming periods of stress,

- Benchmark the indicators and metrics against what was observed during the great financial crisis and Covid-19,

- Create suitable reporting frameworks to ensure the knowledge gathered from the above points is shared with relevant teams, supporting early remediation of issues.

Conclusion

During extreme stresses such as Covid-19 and the global financial crisis, banks’ internal models can fail, not because of modelling issues but due to systemic market issues. Under FRTB, the BCBS show that they recognise this and, in these rare situations, may provide exemptions. The EBA’s recently published technical standards provide better guidance on which indicators can be used to identify these periods of extreme stresses. Although they do not lay out a prescriptive and definitive set of indicators, the technical standards provide a starting point for banks to develop suitable monitoring frameworks.

For more information on this topic, contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Hardial Kalsi (Manager).

The Ridge Backtest Metric: Backtesting Expected Shortfall

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

Challenges with backtesting Expected Shortfall

Recent regulations are increasingly moving toward the use of Expected Shortfall (ES) as a measure to capture risk. Although ES fixes many issues with VaR, there are challenges when it comes to backtesting.

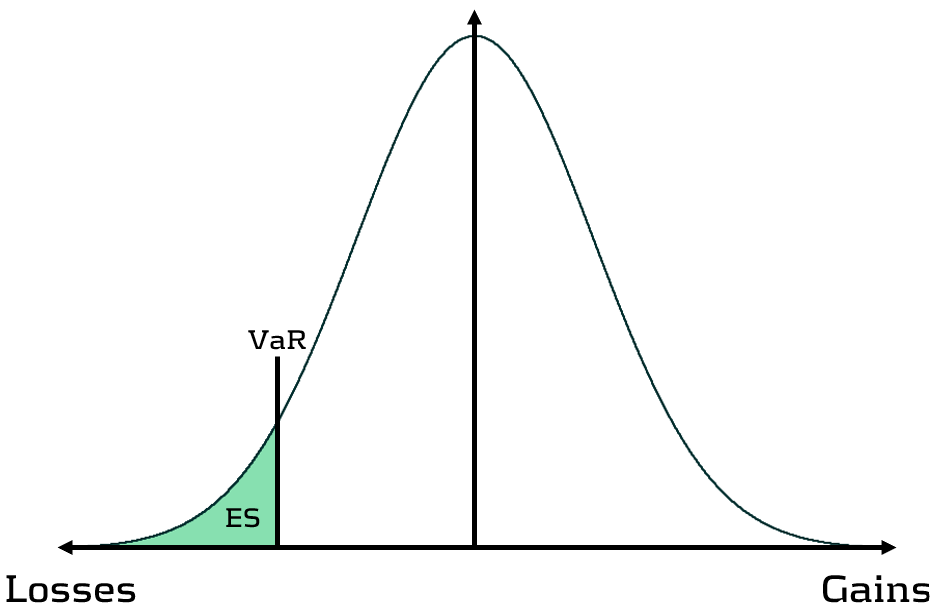

Although VaR has been widely-used for decades, its shortcomings have prompted the switch to ES. Firstly, as a percentile measure, VaR does not adequately capture tail risk. Unlike VaR, which gives the maximum expected portfolio loss in a given time period and at a specific confidence level, ES gives the average of all potential losses greater than VaR (see figure 1). Consequently, unlike Var, ES can capture a range of tail scenarios. Secondly, VaR is not sub-additive. ES, however, is sub-additive, which makes it better at accounting for diversification and performing attribution. As such, more recent regulation, such as FRTB, is replacing the use of VaR with ES as a risk measure.

Figure 1: Comparison of VaR and ES

Elicitability is a necessary mathematical condition for backtestability. As ES is non-elicitable, unlike VaR, ES backtesting methods have been a topic of debate for over a decade. Backtesting and validating ES estimates is problematic – how can a daily ES estimate, which is a function of a probability distribution, be compared with a realised loss, which is a single loss from within that distribution? Many existing attempts at backtesting have relied on approximations of ES, which inevitably introduces error into the calculations.

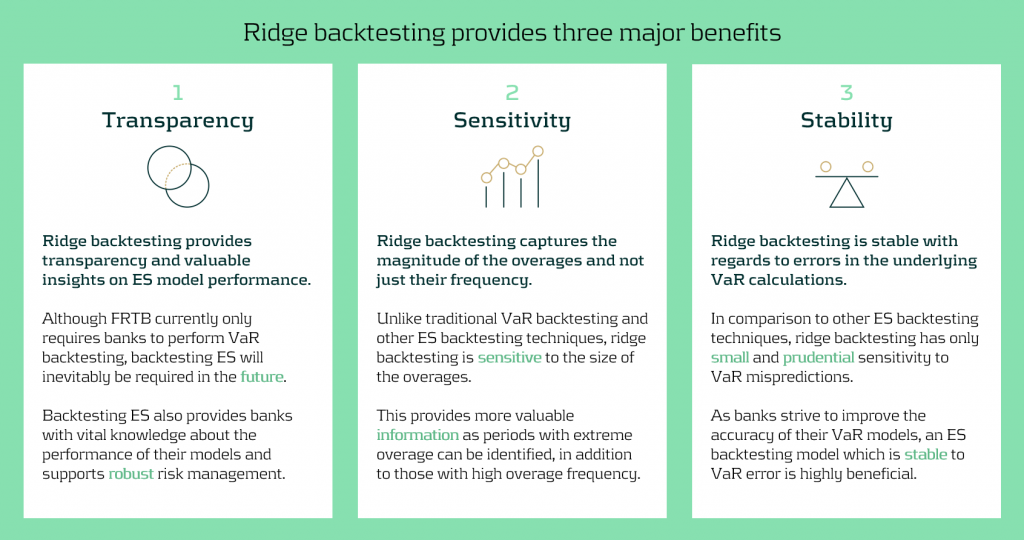

The three main issues with ES backtesting can be summarised as follows:

- Transparency

- Without reliable techniques for backtesting ES, banks struggle to have transparency on the performance of their models. This is particularly problematic for regulatory compliance, such as FRTB.

- Sensitivity

- Existing VaR and ES backtesting techniques are not sensitive to the magnitude of the overages. Instead, these techniques, such as the Traffic Light Test (TLT), only consider the frequency of overages that occur.

- Stability

- As ES is conditional on VaR, any errors in VaR calculation lead to errors in ES. Many existing ES backtesting methodologies are highly sensitive to errors in the underlying VaR calculations.

Ridge Backtesting: A solution to ES backtesting

One often-cited solution to the ES backtesting problem is the ridge backtesting approach. This method allows non-elicitable functions, such as ES, to be backtested in a manner that is stable with regards to errors in the underlying VaR estimations. Unlike traditional VaR backtesting methods, it is also sensitive to the magnitude of the overages and not just their frequency.

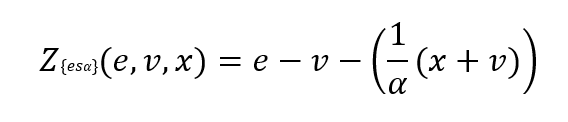

The ridge backtesting test statistic is defined as:

where 𝑣 is the VaR estimation, 𝑒 is the expected shortfall prediction, 𝑥 is the portfolio loss and 𝛼 is the confidence level for the VaR estimation.

The value of the ridge backtesting test statistic provides information on whether the model is over or underpredicting the ES. The technique also allows for two types of backtesting; absolute and relative. Absolute backtesting is denominated in monetary terms and describes the absolute error between predicted and realised ES. Relative backtesting is dimensionless and describes the relative error between predicted and realised ES. This can be particularly useful when comparing the ES of multiple portfolios. The ridge backtesting result can be mapped to the existing Basel TLT RAG zones, enabling efficient integration into existing risk frameworks.

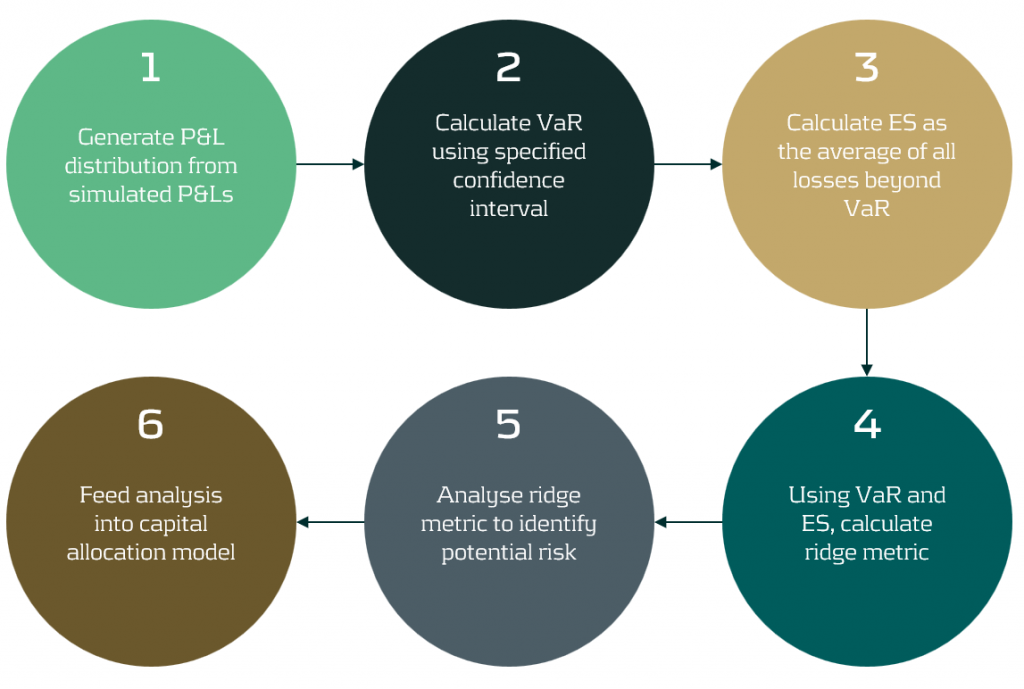

Figure 2: The ridge backtesting methodology

Sensitivity to Overage Magnitude

Unlike VaR backtesting, which does not distinguish between overages of different magnitudes, a major advantage of ES ridge backtesting is that it is sensitive to the size of each overage. This allows for better risk management as it identifies periods with large overages and also periods with high frequency of overages.

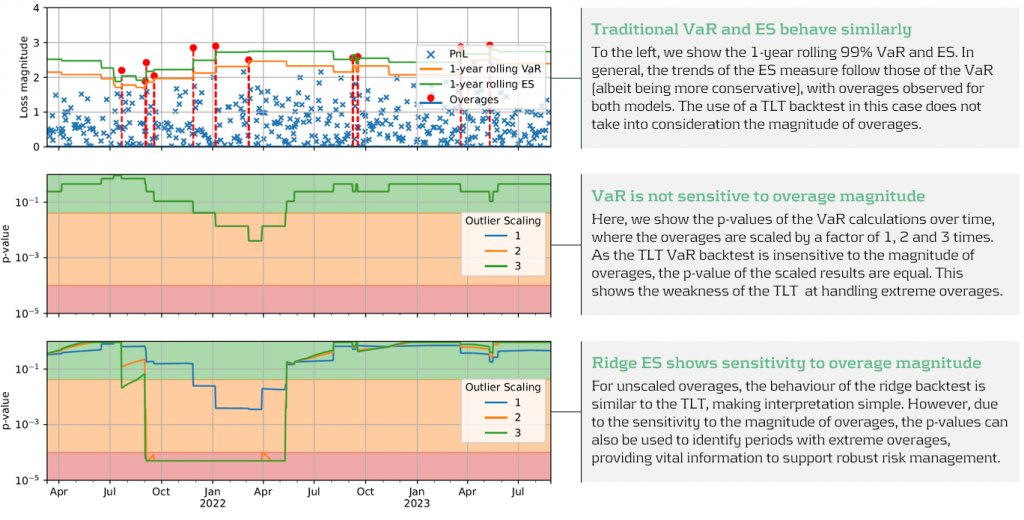

Below, in figure 3, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the ridge backtest by comparing it against a traditional VaR backtest. A scenario was constructed with P&Ls sampled from a Normal distribution, from which a 1-year 99% VaR and ES were computed. The sensitivity of ridge backtesting to overage magnitude is demonstrated by applying a range of scaling factors, increasing the size of overages by factors of 1, 2 and 3. The results show that unlike the traditional TLT, which is sensitive only to overage frequency, the ridge backtesting technique is effective at identifying both the frequency and magnitude of tail events. This enables risk managers to react more quickly to volatile markets, regime changes and mismodelling of their risk models.

Figure 3: Demonstration of ridge backtesting’s sensitivity to overage magnitude.

The Benefits of Ridge Backtesting

Rapidly changing regulation and market regimes require banks enhance their risk management capabilities to be more reactive and robust. In addition to being a robust method for backtesting ES, ridge backtesting provides several other benefits over alternative backtesting techniques, providing banks with metrics that are sensitive and stable.

Despite the introduction of ES as a regulatory requirement for banks choosing the internal models approach (IMA), regulators currently do not require banks to backtest their ES models. This leaves a gap in banks’ risk management frameworks, highlighting the necessity for a reliable ES backtesting technique. Despite this, banks are being driven to implement ES backtesting methodologies to be compliant with future regulation and to strengthen their risk management frameworks to develop a comprehensive understanding of their risk.

Ridge backtesting gives banks transparency to the performance of their ES models and a greater reactivity to extreme events. It provides increased sensitivity over existing backtesting methodologies, providing information on both overage frequency and magnitude. The method also exhibits stability to any underlying VaR mismodelling.

In figure 4 below, we summarise the three major benefits of ridge backtesting.

Figure 4: The three major benefits of ridge backtesting.

Conclusion

The lack of regulatory control and guidance on backtesting ES is an obvious concern for both regulators and banks. Failure to backtest their ES models means that banks are not able to accurately monitor the reliability of their ES estimates. Although the complexities of backtesting ES has been a topic of ongoing debate, we have shown in this article that ridge backtesting provides a robust and informative solution. As it is sensitive to the magnitude of overages, it provides a clear benefit in comparison to traditional VaR TLT backtests that are only sensitive to overage frequency. Although it is not a regulatory requirement, regulators are starting to discuss and recommend ES backtesting. For example, the PRA, EBA and FED have all recommended ES backtesting in some of their latest publications. However, despite the fact that regulation currently only requires banks to perform VaR backtesting, banks should strive to implement ES backtesting as it supports better risk management.

For more information on this topic, contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Hardial Kalsi (Manager).

Exploring IFRS 9 Best Practices: Insights from Leading European Banks

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

Across the whole of Europe, banks apply different techniques to model their IFRS9 Expected Credit Losses on a best estimate basis. The diverse spectrum of modelling techniques raises the question: what can we learn from each other, such that we all can improve our own IFRS 9 frameworks? For this purpose, Zanders hosted a webinar on the topic of IFRS 9 on the 29th of May 2024. This webinar was in the form of a panel discussion which was led by Martijn de Groot and tried to discuss the differences and similarities by covering four different topics. Each topic was discussed by one panelist, who were Pieter de Boer (ABN AMRO, Netherlands), Tobia Fasciati (UBS, Switzerland), Dimitar Kiryazov (Santander, UK), and Jakob Lavröd (Handelsbanken, Sweden).

The webinar showed that there are significant differences with regards to current IFRS 9 issues between European banks. An example of this is the lingering effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is more prominent in some countries than others. We also saw that each bank is working on developing adaptable and resilient models to handle extreme economic scenarios, but that it remains a work in progress. Furthermore, the panel agreed on the fact that SICR remains a difficult metric to model, and, therefore, no significant changes are to be expected on SICR models.

Covid-19 and data quality

The first topic covered the COVID-19 period and data quality. The poll question revealed widespread issues with managing shifts in their IFRS 9 model resulting from the COVID-19 developments. Pieter highlighted that many banks, especially in the Netherlands, have to deal with distorted data due to (strong) government support measures. He said this resulted in large shifts of macroeconomic variables, but no significant change in the observed default rate. This caused the historical data not to be representative for the current economic environment and thereby distorting the relationship between economic drivers and credit risk. One possible solution is to exclude the COVID-19 period, but this will result in the loss of data. However, including the COVID-19 period has a significant impact on the modelling relations. He also touched on the inclusion of dummy variables, but the exact manner on how to do so remains difficult.

Dimitar echoed these concerns, which are also present in the UK. He proposed using the COVID-19 period as an out-of-sample validation to assess model performance without government interventions. He also talked about the problems with the boundaries of IFRS 9 models. Namely, he questioned whether models remain reliable when data exceeds extreme values. Furthermore, he mentioned it also has implications for stress testing, as COVID-19 is a real life stress scenario, and we might need to think about other modelling techniques, such as regime-switching models.

Jakob found the dummy variable approach interesting and also suggested the Kalman filter or a dummy variable that can change over time. He pointed out that we need to determine whether the long term trend is disturbed or if we can converge back to this trend. He also mentioned the need for a common data pipeline, which can also be used for IRB models. Pieter and Tobia agreed, but stressed that this is difficult since IFRS 9 models include macroeconomic variables and are typically more complex than IRB.

Significant Increase in Credit Risk

The second topic covered the significant increase in credit risk (SICR). Jakob discussed the complexity of assessing SICR and the lack of comprehensive guidance. He stressed the importance of looking at the origination, which could give an indication on the additional risk that can be sustained before deeming a SICR.

Tobia pointed out that it is very difficult to calibrate, and almost impossible to backtest SICR. Dimitar also touched on the subject and mentioned that the SICR remains an accounting concept that has significant implications for the P&L. The UK has very little regulations on this subject, and only requires banks to have sufficient staging criteria. Because of these reasons, he mentioned that he does not see the industry converging anytime soon. He said it is going to take regulators to incentivize banks to do so. Dimitar, Jakob, and Tobia also touched upon collective SICR, but all agreed this is difficult to do in practice.

Post Model Adjustments

The third topic covered post model adjustments (PMAs). The results from the poll question implied that most banks still have PMAs in place for their IFRS 9 provisions. Dimitar responded that the level of PMAs has mostly reverted back to the long term equilibrium in the UK. He stated that regulators are forcing banks to reevaluate PMAs by requiring them to identify the root cause. Next to this, banks are also required to have a strategy in place when these PMAs are reevaluated or retired, and how they should be integrated in the model risk management cycle. Dimitar further argued that before COVID-19, PMAs were solely used to account for idiosyncratic risk, but they stayed around for longer than anticipated. They were also used as a countercyclicality, which is unexpected since IFRS 9 estimations are considered to be procyclical. In the UK, banks are now building PMA frameworks which most likely will evolve over the coming years.

Jakob stressed that we should work with PMAs on a parameter level rather than on ECL level to ensure more precise adjustments. He also mentioned that it is important to look at what comes before the modelling, so the weights of the scenarios. At Handelsbanken, they first look at smaller portfolios with smaller modelling efforts. For the larger portfolios, PMAs tend to play less of a role. Pieter added that PMAs can be used to account for emerging risks, such as climate and environmental risks, that are not yet present in the data. He also stressed that it is difficult to find a balance between auditors, who prefer best estimate provisions, and the regulator, who prefers higher provisions.

Linking IFRS 9 with Stress Testing Models

The final topic links IFRS 9 and stress testing. The poll revealed that most participants use the same models for both. Tobia discussed that at UBS the IFRS 9 model was incorporated into their stress testing framework early on. He pointed out the flexibility when integrating forecasts of ECL in stress testing. Furthermore, he stated that IFRS 9 models could cope with stress given that the main challenge lies in the scenario definition. This is in contrast with others that have been arguing that IFRS 9 models potentially do not work well under stress. Tobia also mentioned that IFRS 9 stress testing and traditional stress testing need to have aligned assumptions before integrating both models in each other.

Jakob agreed and talked about the perfect foresight assumption, which suggests that there is no need for additional scenarios and just puts a weight of 100% on the stressed scenario. He also added that IFRS 9 requires a non-zero ECL, but a highly collateralized portfolio could result in zero ECL. Stress testing can help to obtain a loss somewhere in the portfolio, and gives valuable insights on identifying when you would take a loss.

Pieter pointed out that IFRS 9 models differ in the number of macroeconomic variables typically used. When you are stress testing variables that are not present in your IFRS 9 model, this could become very complicated. He stressed that the purpose of both models is different, and therefore integrating both can be challenging. Dimitar said that the range of macroeconomic scenarios considered for IFRS 9 is not so far off from regulatory mandated stress scenarios in terms of severity. However, he agreed with Pieter that there are different types of recessions that you can choose to simulate through your IFRS 9 scenarios versus what a regulator has identified as systemic risk for an industry. He said you need to consider whether you are comfortable relying on your impairment models for that specific scenario.

This topic concluded the webinar on differences and similarities across European countries regarding IFRS 9. We would like to thank the panelists for the interesting discussion and insights, and the more than 100 participants for joining this webinar.

Interested to learn more? Contact Kasper Wijshoff, Michiel Harmsen or Polly Wong for questions on IFRS 9.

Environmental and social risks in the prudential framework: Possible implications for banks

Explore how ridge backtesting addresses the intricate challenges of Expected Shortfall (ES) backtesting, offering a robust and insightful approach for modern risk management.

In October 2023, the European Banking Authority (EBA) published a report[1] with recommendations for enhancements to the Pillar 1 prudential framework to reflect environmental and social (E&S) risks, distinguishing between actions to be taken in the short term and in the medium to long term. The short-term actions are to be taken into account over the next three years as part of the implementation of the revised Capital Requirements Regulation and Capital Requirements Directive (CRR3/CRD6).

The EBA report follows a discussion paper on the same topic from May 2022[2], on which it solicited input from the financial industry. In this note, we provide an overview of the recommended actions by the EBA that relate to the prudential framework for banks. The EBA report also contains recommended actions for the prudential framework applying to investment firms, but these are not addressed here.

If the EBA’s recommendations are implemented in the prudential framework, in our view the most immediate implications for banks would be:

- When using external ratings to determine own fund requirements for credit risk under the standardized approach (SA) of Pillar 1, ensure that E&S risks are explicitly considered when evaluating the appropriateness of the external ratings as part of the due diligence requirements.

- When calculating own fund requirements for credit risk under the internal-ratings-based (IRB) approach, embed E&S risks in the rating assignment, risk quantification (for example through a margin of conservatism or the downturn component) and/or expert judgment and overrides.

- To assess E&S risks at a borrower level, establish a process to obtain and update material E&S-related information on the borrowers’ financial condition and credit facility characteristics, as part of due diligence during onboarding and ongoing monitoring of the borrowers’ risk profile.

- For IRB banks, embed E&S risks in the credit risk stress testing programs.

- Ensure that E&S risks are considered in the valuation of collateral, specifically for financial and real estate collateral.

- For market risk, embed environmental risks in trading book risk appetite, internal trading limits and the new product approval process. Furthermore, for banks aiming to use the internal model approach (IMA) of the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) regulation, environmental risks need to be considered in their stress testing program.

- For operational risk, identify whether E&S risks constitute triggers of operational risk losses.

We note that many of these implications align with the ECB’s expectations in the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks[3].

Background

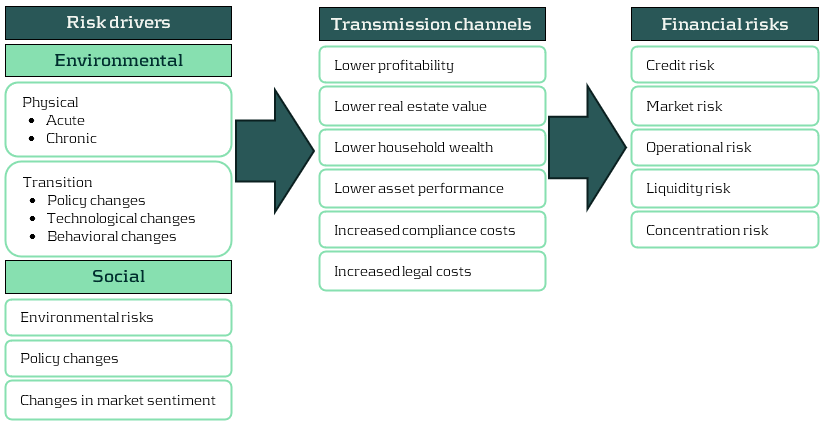

The EBA report considers both environmental and social risks, which the EBA characterizes as follows:

- As drivers of environmental risks, EBA distinguishes physical and transition (climate) risks. It does not explicitly refer in the report to other environmental risks, such as a loss of biodiversity or pollution, but in an earlier report the EBA considered these as part of chronic physical risks[4].

- EBA considers social factors to be related to the rights, well-being and interests of people and communities, including factors such as decent work, adequate living standards, inclusive and sustainable communities and societies, and human rights. As drivers of social risks, EBA distinguishes environmental factors (as materialization of physical and transition risks may change living standards and the labor market and increase social tensions, for example) as well as changes in policies and market sentiment. These may in part be driven by actions taken to meet the United Nation’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) in 2030.

In line with the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks[5], the EBA does not view E&S risks as stand-alone risks, but as drivers of traditional banking risks. This is depicted in Figure 1. The report considers the impact on credit, market, operational, liquidity and concentration risks and reviews to what extent E&S risks can be reflected in capital buffers and the macro-prudential framework. It does not explicitly consider the securitization framework, although this will be implicitly affected by impacts on credit risk. The EBA does not see an impact of E&S risks on the (risk-insensitive) leverage ratio, and therefore does not consider it in the report.

Figure 1: Examples of transmission channels for environmental and social risks (source: EBA).

The EBA notes that the Pillar 1 framework has been designed to capture the possible financial impact of cyclical economic fluctuations, but not to capture the manifestation of long-term environmental risks. It is therefore important to keep the main principles that form the basis of the prudential framework in mind when contemplating adjustments to reflect E&S risks in the prudential framework. The main principles as highlighted by the EBA are summarized below.

Main principles of the prudential framework and the relation to the horizon for E&S risks

With repect to the framework in general:

- Own fund requirements are intended to cover potential unexpected losses. In contrast, expected losses are directly deducted from own funds, and are generally captured in the accounting rules through provisions, impairments, write-downs and appropriate valuation of assets.

- The purpose of own fund requirements is to ensure resilience of an institution to unexpected adverse circumstances, before appropriate mitigating actions and strategy adjustments can be implemented. Therefore, environmental factors that can affect institutions in the short to medium term are expected to be reflected in the prudential framework. However, for those with an impact in the longer term, institutions are expected to take appropriate mitigating actions in their strategy.

- The high confidence level used in the Pillar 1 framework to protect institutions from risks over the short to medium horizon may no longer be achievable and appropriate if longer horizons would be considered.

- To the extent that institutions are exposed to E&S risks in relation to their specific strategy and business model, coverage of these risks in the Pillar 2 own-fund requirements instead of Pillar 1 could be appropriate. In addition, reflection of these risks in the Pillar 2 guidance for stress testing may be considered.

With respect to the internal-ratings-based (IRB) approach for credit risk:

- The Probability of Default (PD) represents a one-year default probability, which is required to be calibrated based on long-run average (‘through-the-cycle’) default rates. As such, longer-term risk characteristics of the obligor may be taken into account.

- The Credit Conversion Factor (CCF) as an estimate of potential additional drawdowns before default naturally relates to the one-year time horizon for the PD, but is expected to reflect the situation of an economic downturn.

- The time horizon for the Loss Given Default (LGD) extends to the full maturity of the exposure and/or the collection process and its calibration is also expected to reflect the situation of an economic downturn.

In the following sections we summarize the EBA recommendations by risk type.

Credit risk

The recommendations of the EBA largely put the burden on financial institutions to take E&S risks into account in the inputs for the existing Pillar 1 framework and/or to apply conservatism or overrides to the outputs. It does not recommend to include explicit E&S risk-related elements in the determination of risk weights for rated and unrated exposures in the SA or in the risk-weight formulas of the IRB. The main reasons for not doing so are that it is not clear what common and objective E&S-related factors should be used as input, what the proper functional form would be, a lack of evidence on which the size of an adjustment could be based so that it results in proper risk differentiation, and the risk of double counting with the reflection of E&S risks in the inputs to the existing own funds calculations under Pillar 1 (external ratings in the SA and PD, LGD and CCF in the case of IRB). However, the EBA will continue to evaluate this possibility in the medium to long term. The EBA also does not recommend introducing an environment-related adjustment factor to the risk weights resulting from the existing Pillar 1 framework[6].

Recommended actions for credit risk

| Short term |

- SA) The EBA encourages rating agencies to integrate environmental and social factors as drivers in the external credit risk assessments and to provide enhanced disclosures and transparency about the rating methodologies.

- (SA) Financial institutions to explicitly consider environmental factors in the due diligence that they are required to perform when using external credit risk assessments.

- (IRB) Financial institutions to reflect E&S risks in the rating assignment, risk quantification (for example through a margin of conservatism or the downturn component) and/or expert judgment and overrides, without affecting the overall performance of the rating system. In this context:

- Quantification of risks must be based on sufficient and reliable observations;

- Overrides should be for specific, individual cases where the institution believes there is material exposure to E&S risks but it has insufficient information to quantify it. Such overrides need to be regularly assessed and challenged;

- If an institution derives PDs for internal rating grades by a mapping to a scale from a credit rating institution, it needs to consider whether the default rates associated with the external scale reflect material E&S risks.

- To assess E&S risks at a borrower level, institutions need to have a process to obtain and update material E&S-related information on the borrowers’ financial condition and on credit facility characteristics, as part of the due diligence during onboarding and ongoing monitoring of borrowers’ risk profile.

- (IRB) Financial institutions to consider E&S risks in their stress testing programs.

- (SA, IRB) Financial institutions to ensure prudent valuation of immovable property collateral, considering climate-related physical and transition risks as well as other environmental risks. The prudent valuation should be considered at origination, re-valuation and during monitoring.

| Medium to long term |

- (SA) Financial institutions to monitor that environmental factors are reflected in financial collateral valuations through market values under Pillar 1 and valuation methodologies under Pillar 2.

- (SA) The EBA to consider whether benefits from the Infrastructure Supporting Factor (ISF) should only be applied to high-quality specialized lending corporate exposures that meet strong environmental standards.

- (SA) The EBA to consider adjusting risk weights, both in general and specifically for those assigned to real estate exposures.

- (IRB) As E&S risks materialize in defaults and loss rates over time, institutions need to redevelop or recalibrate their PD and LGD estimates.

(SA = standardized approach; IRB = Internal-rating-based approach)

Market risk

Within market risk, the EBA sees the main interaction of E&S risks with the equity, credit spread and commodity markets, in which E&S risks may cause additional volatility. In line with the existing regulatory guidance, the EBA expects E&S risks not to be treated as separate risk factors but as drivers of existing risk factors, with the exception of products for which cash flows depend specifically on ESG factors (‘ESG-linked products’).

The EBA does not recommend changes at this point to the standardized approach (SA) and the internal model approach (IMA) under the FRTB regulation, which will come into effect in the EU in 2025. The primary reason is the lack of sufficient evidence on the impact of E&S risks to enable a data driven approach, which forms the basis of the FRTB.