In December 2024, FINMA published a new circular on nature-related financial risks. Read our main take-aways.

Introduction

In December 2024, FINMA published a new circular on nature-related financial (NRF) risks. Our main take-aways:

- NRF risks not only comprise climate-related risks, but also other nature-related risks (such as loss of biodiversity, invasive species and degradation in the quality of air, water and soil). However, risks other than climate-related risks only need to be covered in 2028, whereas climate-related risks need to be covered by 2026 (for large institutions) and 2027 (for small institutions).

- All institutions independent of size need to perform a risk identification and materiality assessment of NRF risks.

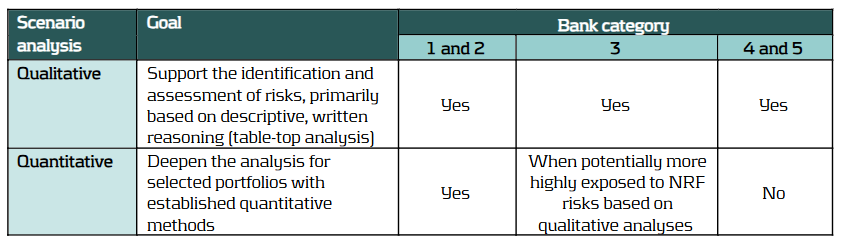

- As part of the materiality assessment, banks need to perform scenario analysis. Small institutions may limit themselves to qualitative scenario analysis, whereas large banks need to perform quantitative scenario analysis.

In this blog we summarize the contents of the circular as applicable to banks, including the additional guidance provided by FINMA (“Erläuterungen”).

FINMA states the following aims for publishing the circular:

- Clarify expectations about the management of nature-related financial (NRF) risks by supervised institutions, based on existing laws and regulations.

- Support supervised institutions to adequately identify, assess, limit and monitor these risks.

- Be lean, principle-based, proportional, technology-neutral, and internationally aligned1.

The circular applies to both banks and insurance companies in Switzerland, including branches of foreign institutions.

The scope of application depends on the bank category:

- Category 4 and 5 banks that are very well capitalized and very liquid (‘Kleinbankenregime’) are exempted from implementation of the circular.

- Other category 4 and 5 banks are exempted from quantitative scenario analysis, whereas category 3 banks only need to perform quantitative scenario analysis for portfolios with heightened exposure to NRF risks.

- Category 3, 4 and 5 banks are exempted from consideration of material NRF risks in stress tests.

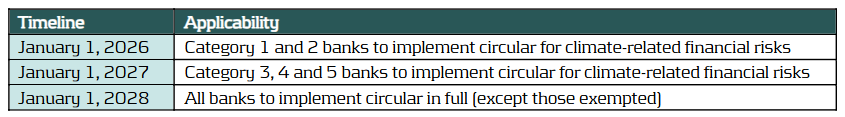

The circular has to be implemented in full by January 1, 2028, for all banks in scope. However, implementation for climate-related risks needs to be completed earlier, as outlined in the table below, reflecting the greater maturity in the assessment of climate-related risks:

FINMA emphasizes that banks will need to have completed their risk identification & materiality assessment well before the overall implementation timeline to allow sufficient time to embed material NRF risks in the overall risk management framework in line with the other parts of the circular.

Definitions

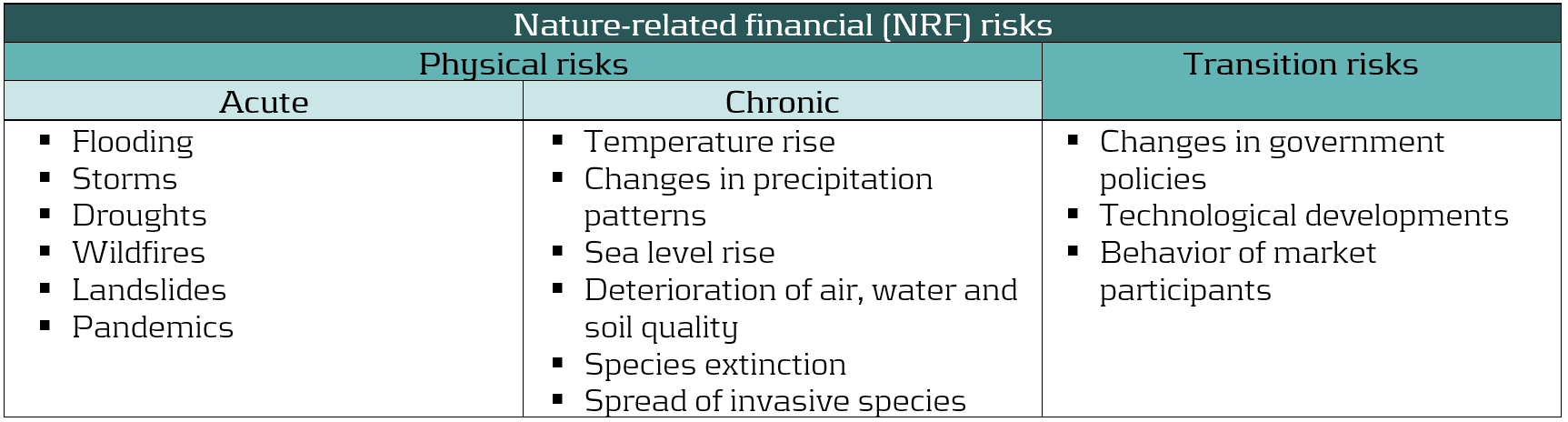

FINMA distinguishes the following types and examples of NRF risks:

The circular does not adopt a ‘double materiality’ perspective but focuses on the potential financial impact of NRF risks on a financial institution. However, FINMA emphasizes that the impact of an institution on its environment (e.g., through the lending and investment activities) can influence the relevance of NRF risks for the institution.

General expectations

The circular emphasizes that all banks need to perform a risk identification and materiality assessment of NRF risks, independent of size and bank category. Implementation of the other parts of the circular depends on whether and which material NRF risks have been identified.

Governance

As all banks need to perform a risk identification and materiality assessment of NRF risks, all banks also need to set up an appropriate governance under which this takes place, including definition and documentation of tasks, competencies and responsibilities. This needs to cover the management and supervisory boards as well as the independent control functions. For management and supervisory boards, it is specifically important to reflect material NRF risks in the business and risk strategy. The nature of the governance arrangements can reflect the size and complexity of the institution (proportionality).

Risk identification and materiality assessment

Each bank needs to identify all NRF risks that may impact the institution’s risk profile and assess the potential financial materiality. This should include

- the potential strategic impact, driven by changing expectations from the public and authorities and consequential changes in markets and technologies, as well as

- potential legal and reputational risks through lawsuits against the bank’s counterparties or the bank itself as well as through increasing regulation

The risk identification needs to be performed on a gross (inherent) basis. A net (residual) risk can be considered in addition if the effectiveness of risk mitigation measures can be substantiated.

FINMA emphasizes that NRF risks need to be considered as risk drivers of existing risk types, rather than as new stand-alone risks. For the existing risk types, at least credit, market, liquidity, operational, compliance, legal and reputational risk need to be considered. Moreover, concentration risks driven by NRF risks need to be considered both within and across the existing risk types. For example, transition risks can simultaneously lower the creditworthiness of counterparties (credit risk), decrease the value of investment positions (market risk) and affect the reputation of the institution (reputation risk). Hence, significant exposure to sectors that are sensitive to transition risk, such as fossil fuel and transport, can lead to additional concentration risk.

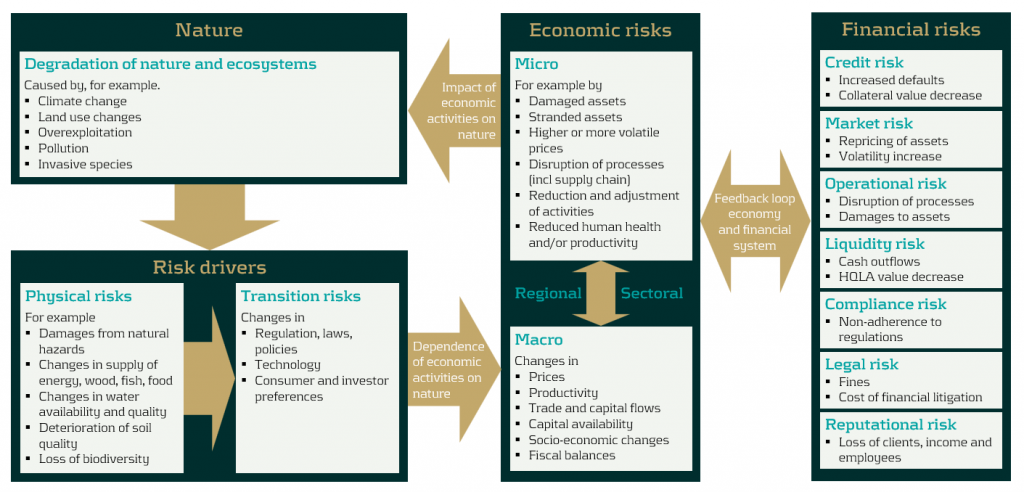

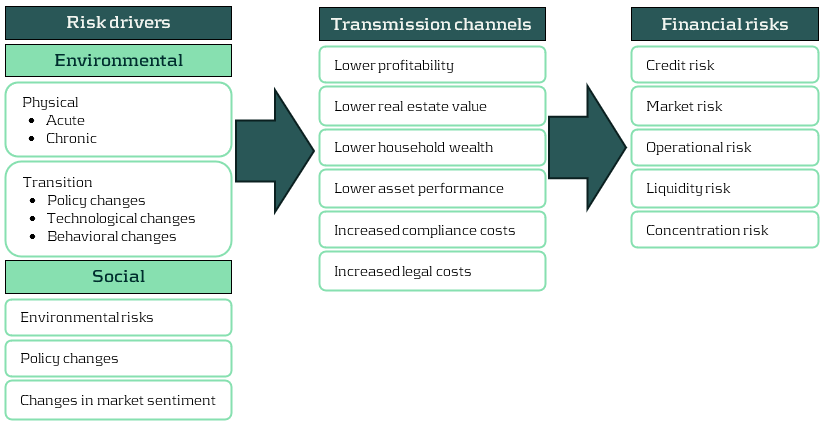

To assess the financial materiality, institutions are expected to understand the transmission channels through which NRF risks can materialize in financial risks. The following chart provides an illustration of possible transmission channels.

Source: Adapted from Figure 2 in NGFS, Nature-related Financial Risks: a Conceptual Framework to guide Action by Central Banks and Supervisors, July 2024.

In performing the materiality assessment, the institution should consider all relevant internal and external information, consider the indirect impact of NRF risks through clients and related third parties and pay attention to its exposure to sectors, regions and jurisdictions with heightened NRF risks.

The process and results of the risk identification and materiality assessment need to be clearly documented, including:

- Criteria and assumptions used, such as scenarios and time horizons considered

- Physical and transition risks considered and their impact on traditional risk types

- The applicable time horizon for the financial materiality

- NRF risks that were assessed as non-material

The risk identification and materiality assessment needs to be updated regularly, for which FINMA suggests linking it to the annual business planning process.

FINMA emphasizes the central role that scenario analysis plays in the materiality assessment. In this respect it expects banks to

- Use at least qualitative considerations how adverse scenarios could impact the business model

- Consider multiple scenarios, including those with a low probability and possibly large impact

- Consider direct impacts and indirect impacts (e.g., on clients and suppliers and their supply chains) from NRF risks

- Use multiple relevant time horizons (short, medium and long term)

In the additional guidance, FINMA indicates that publicly available scenarios can be used (such as those from the NGFS) but they may need to be tailored to the characteristics of the institution.

FINMA expects all banks to perform qualitative scenario analyses, but expects quantitative scenario analysis only at larger institutions, as summarized in the following table.

In addition to scenario analysis, FINMA expects banks to use other quantitative approaches (such as sector exposures) to substantiate the materiality assessment.

Risk Management

Material NRF risks need to be integrated in the existing processes for the management, monitoring, controlling and reporting of existing risk types. Risk tolerances for exposure to material NRF risks need to be reflected in risk indicators with warning levels and limits and include forward-looking indicators. For example, risk tolerance for transition risk can be expressed in terms of the nominal exposure and/or financed CO2 emissions in sectors that are sensitive to transition risks, including targets for a reduction in the exposure over time.

To account for the large uncertainty in existing methods and data, institutions are expected to apply a margin of conservatism in the risk tolerances (“Vorsichtsprinzip”). Furthermore, they are expected to regularly evaluate, and when necessary, amend, the data, methods and processes needed to manage material NRF risks. This evaluation needs to take national and international developments into account. In the additional guidance, FINMA emphasizes the importance of describing in the existing documentation of the risk management and control processes how material NRF risks are managed, including required data such as transition plans and physical locations of counterparties as well as assumptions, approximations and estimates used when proper data is still lacking.

In addition, firms are expected to verify regularly whether their publicly disclosed sustainability objectives are aligned with their business strategy, risk tolerance, risk management and legal requirements, such as national or international commitments to reduce emissions and protect biodiversity. Any such misalignments would increase legal and reputational risks. To reduce the risk of such misalignments, FINMA suggests to include the publicly stated objectives in the annual targets for business lines and employees and embed them in the internal control reviews.

Stress testing

Category 1 and 2 banks with material NRF risks need to integrate these in their stress test and the internal capital adequacy assessment. To define stress tests, scenarios that have been used for the materiality assessment can be used as basis, but they may need to be broadened in scope and made more severe.

Expectations per risk type

The FINMA expectations per risk type below apply to material NRF risks only.

Credit risk

NRF risks that are assessed as material in relation to a bank’s credit risk need to be monitored throughout the full lifecycle of credit risk positions. The bank is expected to consider measures to control or reduce the exposure to these NRF risks, for example by

- Adjusting the lending criteria and, if applicable, acceptable collateral. As part of this, the bank can consider providing incentives to counterparties to reduce exposure to NRF risks.

- Adjusting client or transaction ratings.

- Lending restrictions, such as shorter maturities, lower lending limits and discounted asset values for clients materially exposed to NRF risks.

- Client engagement, encouraging sustainable business practices and enhanced external disclosures about exposures to NRF risks and transition plans.

- Setting thresholds or other risk mitigation techniques for activities, counterparties, sectors and regions which are not in line with the risk tolerance. For example, in highly sensitive sectors, the bank may restrict exposures to those counterparties with credible transition plans.

Market risk

Institutions with material NRF risk exposure in their market risk positions need to assess the loss potential and the impact of increased volatility in relation to the potential materialization of NRF risks. Category 1 to 3 banks with material NRF risks need to do so regularly. The market risk positions cover both trading book positions (bonds, equities, FX, commodities) and banking book investments.

The loss potential can be assessed using scenario analyses and stress tests that

- Are forward looking and also cover medium and long-term horizons

- Consider the impact of a sudden shock on the value of financial instruments

- Reflect dependencies between market variables

- Embed forward-looking assumptions rather than historical distributions

- Take into account the prices and availability of hedges under different scenarios (e.g., in a ‘disorderly transition’ scenario)

FINMA notes that the impact of NRF risks on managed investments can lead to business risk (lower revenues) when other institutions are better managing them for their clients.

Liquidity risk

Examples of the potential impact of NRF risks on a bank’s liquidity position are clients hoarding cash ahead of, or withdrawing funds for repairs after, a natural disaster. FINMA stipulates that banks with material exposure to NRF risks need to evaluate the impact in normal and adverse situations. Material impacts need to be controlled or mitigated.

To assess the potential impact, FINMA suggests that banks can consider a combined market-wide and idiosyncratic stress situation in combination with the occurrence of a natural disaster (e.g., a flooding). Not only cash outflows need to considered, but also the impact on the value of financial instruments that are part of the stock of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA). Any material impact needs to be considered in the calibration of the necessary amount of HQLA and the management of liquidity risks.

Operational risk

Banks with material NRF risks in relation to operational risks need to consider these in risk and control assessments (RCA) for operational risk and in the management of operational risks, where appropriate. This is aligned with the expectations in the FINMA Circular 2023/1 “Operational risks and resilience – Banks”.

Category 1 to 3 institutions that perform a systematic collection and analysis of loss data according to FINMA Circular 2023/1 need to clearly show losses and events in relation to NRF risks in relevant reports.

Furthermore, material NRF risks in relation to operational risks that may impair critical functions need to be documented and considered in the operational resilience of the institution as reflected in business-continuity plans and disaster-recovery plans. An example could be the unavailability of a data center due to a natural disaster such as a flooding or severe storm.

Compliance, legal and reputational risk

FINMA sees heightened compliance, legal and reputation risks in relation to NRF risks due to high expectations from society and the government for banks to contribute to achieving society’s sustainability goals. For example, the Swiss government is obliged by law to ensure that the Swiss Financial Sector contributes to a low-emission and climate-resilient development. FINMA expects banks to explicitly assess the potential impact of NRF risks on legal and compliance costs as well as the bank’s reputation. Any such material risks need to embedded in relevant processes and controls.

As potential sources of reputation risks for banks, FINMA mentions the nature of investments and lending, the composition of investment portfolios, project financing, client advisory and marketing campaigns. Reputation risk will have a financial impact when clients and/or the public in general lose trust and stop doing business with the institution, leading to lower revenues. Reputation risk should therefore also be considered in new product development and go-to-market, new business initiatives and new marketing campaigns. FINMA also expects institutions to elaborate on the impact of NRF risks on reputation risk in their external disclosure.

Implementation

To prepare for the implementation of the new FINMA circular, we advise banks to take the steps as outlined below.

1 - Design a process to perform a risk identification and materiality assessment of NRF risks, including the universe of NRF risks to be considered

2 - Execute the process and document the results. This needs to include:

- Identify possible transmission channels for each combination of NRF risk and existing risk type

- Assess potential financial materiality for all transmission channels, using internal and external expertise as well as scenario analysis. For this purpose, suitable scenarios need to be identified.

3 - Decide on metrics (KRIs) for the material NRF risks and identify sources of required data

4 - Agree on risk tolerances for exposure to NRF risks, including KRIs

5 - Embed material NRF risks in internal risk management, monitoring and reporting processes for all relevant risk types (credit, market, liquidity, operational, legal, compliance and reputation risk)

6 - Collect required data and include KRIs in relevant reports

7 - Prepare external disclosure

Based on our experience, completing the steps may well take up to a year, including the time needed for internal discussion and decision taking. Although this can be shortened if the bank has already taken initial steps, we advise banks to start timely with the implementation of the circular.

If you would like to discuss our proposed approach or are looking for an experienced partner to support you in this process, please reach out to Pieter Klaassen.

Citations

- Regarding international alignment, for banks FINMA specifically refers to the BCBS “Principles for the effective management and supervision of climate-related financial risks” (link) and the NGFS paper on “Nature-related risks: A conceptual framework to guide action by central banks and supervisors” (link). ↩︎

Deforestation, pollution, and resource overuse are accelerating biodiversity loss, learn how to quantify your organization’s impact.

Human activities such as deforestation, pollution, and resource over-extraction have caused a dramatic decline in biodiversity, with approximately 1 million species at risk of extinction, highlighting the urgent need for financial institutions to adopt biodiversity footprinting methods to measure and mitigate their environmental impact. According to the 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services by IPBES, about 1 million species are now threatened with extinction due to these human activities (Brondízio, Settele, Diaz, & Ngo, 2019). Moreover, WWF’s 2024 Living Planet Report documents a 73% decline in wildlife populations since 1970 (World Wildlife Fund, 2024). These findings underscore the urgency for action to conserve and restore natural environments.

We previously published articles exploring the importance of biodiversity risks and opportunities for financial institutions (Biodiversity risks and opportunities for financial institutions explained), and introduced a quantitative approach to scoring biodiversity risks based on sector and location (Biodiversity risks scoring: a quantitative approach). Building on those insights, this blog addresses the challenge of quantifying the biodiversity impact of a financial institution. Specifically, it explains biodiversity footprinting: a method enabling financial institutions to measure, track, and ultimately mitigate their environmental impact on biodiversity.

What is biodiversity and why it matters

A commonly used definition of biodiversity is “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 1992). Hence, it represents all living organisms on earth like animals, plants, fungi and microbes, and the complex interactions that form our ecosystems. Biodiversity is the backbone of the earth's life-support systems. It directly affects the air we breathe, the food we eat and the water we drink. Additionally, healthy ecosystems help mitigate climate change by capturing carbon, safeguarding water supplies and maintaining balanced soil nutrients. Furthermore, natural habitats like wetlands, mangroves and forests protect communities from extreme weather events.

Economically, biodiversity is vital too. For example, ENCORE defines ecosystem services as the benefits that nature provides to support economic activities (ENCORE, sd). These services are categorized into provisioning services, which supply resources like food, water, and raw materials; regulating and maintenance services, which include air and water purification, climate regulation, and pest control; and cultural services, offering recreational, educational, and spiritual benefits. Biodiversity is fundamental to the proper functioning of these services.

While many global efforts and investments focus on monitoring and reducing CO2 emissions, much less attention is given to tracking and preventing biodiversity loss. This gap shows a key weakness in our environmental management strategies.

Why it matters for financial institutions

The financial sector plays a critical role in shaping the global economy by directing investments into various ventures, industries, and innovations. Biodiversity loss poses tangible risks (e.g. operational, reputational and regulatory) that financial institutions must address. Ignoring these risks could lead to stranded assets, disrupted supply chains or negative stakeholder reactions (for more about biodiversity risk for financial institutions, see this previous blog. Moreover, integrating biodiversity considerations into decision-making can lead to more resilient investment strategies and unlock new, nature-positive opportunities.

By measuring and monitoring their biodiversity impacts, banks, asset managers, insurers and other financial entities can:

- Learn about and better understand the causes and complexities of biodiversity loss;

- Identify biodiversity hotspots in their portfolios;

- Engage with clients on sustainable practices to reduce their impact;

- Align with global frameworks and evolving regulatory standards.

As awareness of biodiversity risks and opportunities grows, understanding how to measure biodiversity impacts becomes important. Biodiversity footprinting is a helpful tool for this.

What is biodiversity footprinting?

Biodiversity footprinting is a method for quantifying the impact of products, investments, or entire portfolios on natural ecosystems. Similar to measuring a carbon footprint, a biodiversity footprint measures the degree to which an activity affects habitat quality, species abundance, and overall ecological health. This is done by tracking factors like land use, water consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and pollution. The goal is to pinpoint economic activities with significant environmental impact, so that organizations can set informed targets and policies to promote biodiversity conservation.

Quantifying a biodiversity footprint is more challenging than measuring a carbon footprint, as it involves multiple local factors, diverse habitats and various impact types. The complexity and location-specific nature of biodiversity means that universal benchmarks or standardized datasets are still evolving. Today, multiple initiatives and approaches exist, each with its own methods and metrics for assessing biodiversity impacts.

Zanders’ biodiversity footprinting model

Zanders’ model for biodiversity footprinting provides financial institutions with a first scan and quantification of the impacts their financial activities have on natural ecosystems. The methodology is based on the Biodiversity Footprint for Financial Institutions (BFFI), an approach that enables calculation of biodiversity impacts across multiple asset classes.

Our model requires input data on the size of economic activities (in euros), the specific sector or asset type, and the location at a country-level granularity. It integrates this data with important environmental pressures derived from a multi-regional environmentally extended input-output database. Using life cycle assessment techniques, the biodiversity footprint is calculated by determining the Potentially Disappeared Fraction (PDF) of species. This is used to express the total biodiversity loss in square meters (m²) resulting from one year of economic activities.

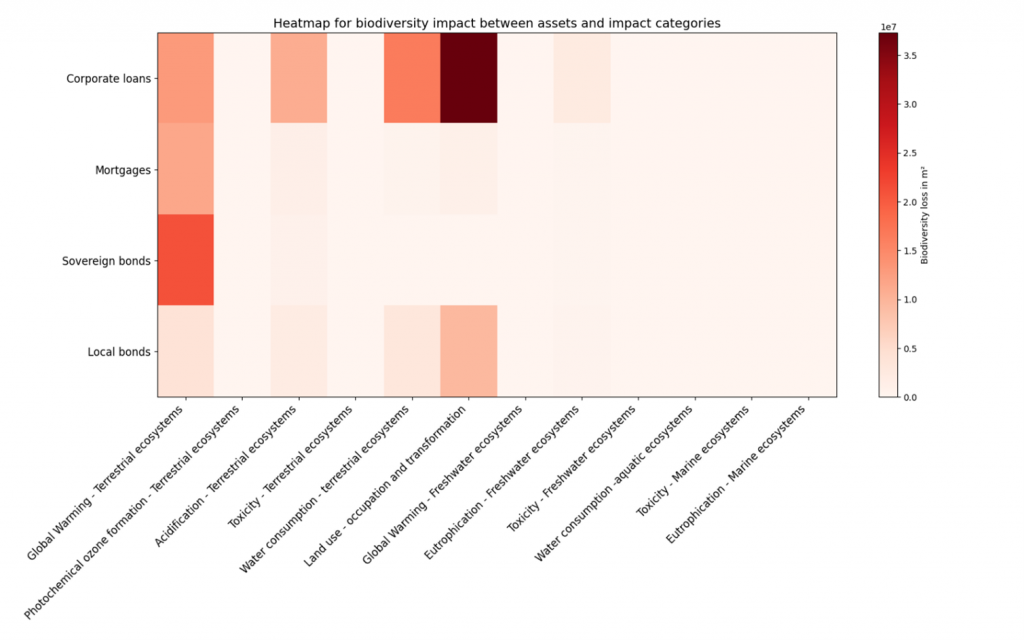

By quantifying these impacts, financial institutions can identify specific biodiversity impact hotspots within their portfolios. This enables them to set informed, science-based targets aimed at effectively reducing their overall biodiversity footprint. The image below illustrates the results for a hypothetical portfolio, highlighting biodiversity impacts across various asset classes and impact categories.

If you are interested in learning more about how Zanders can help you quantify your biodiversity impact, please contact Steyn Verhoeven, Martijn Schouten or Marije Wiersma.

Bibliography

Brondízio, E. S., Settele, J., Diaz, S., & Ngo, H. T. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat.

Convention on Biological Diversity. (1992). Article 2: Biodiversity definition. Retrieved from Convention on Biological Diversity: https://www.cbd.int/convention/articles?a=cbd-02

ENCORE. (n.d.). Ecosystem Services. Retrieved from ENCORE: https://www.encorenature.org/en/data-and-methodology/services

Wiersma, M., Blijlevens, S., & Manzanares, M. (2024, October). Biodiversity risks scoring: a quantitative approach. Retrieved from Zanders: https://zandersgroup.com/en/insights/blog/biodiversity-risks-scoring-a-quantitative-approach

Wiersma, M., Gerrits, J., & Fedenko, I. (2023, November). Biodiversity risks and opportunities for financial institutions explained. Retrieved from Zanders: https://zandersgroup.com/en/insights/blog/biodiversity-risks-and-opportunities-for-financial-institutions-explained

World Wildlife Fund. (2024). Living Planet Report 2024. Retrieved from https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/2024-living-planet-report

Explore how Zanders’ scoring methodology quantifies biodiversity risks, enabling financial institutions to safeguard portfolios from environmental and transition impacts.

Addressing biodiversity (loss) is not only relevant from an impact perspective; it is also quickly becoming a necessity for financial institutions to safeguard their portfolios against financial risks stemming from habitat destruction, deforestation, invasive species and/or diseases.

In a previous article, published in November 2023, Zanders introduced the concept of biodiversity risks, explained how it can pose a risk for financial institutions, and discussed the expectations from regulators.1 In addition, we touched upon our initial ideas to introduce biodiversity risks in the risk management framework. One of the suggestions was for financial institutions to start assessing the materiality of biodiversity risk, for example by classifying exposures based on sector or location. In this article, we describe Zanders’ approach for classifying biodiversity risks in more detail. More specifically, we explore the concepts behind the assessment of biodiversity risks, and we present key insights into methodologies for classifying the impact of biodiversity risks; including a use case.

Understanding biodiversity risks

Biodiversity risks can be related to physical risk and/or transition risk events. Biodiversity physical risks results from environmental decay, either event-driven or resulting from longer-term patterns. Biodiversity transition risks results from developments aimed at preventing or restoring damage to nature. These risks are driven by impacts and dependencies that an undertaking has on natural resources and ecosystem services. The definition of impacts and dependencies and its relation to physical and transitional risks is explained below:

- Companies impact natural assets through their business operations and output. For example, the production process of an oil company in a biodiversity sensitive area could lead to biodiversity loss. Impacts are mainly related to transition risk as sectors and economic activities that have a strong negative impact on environmental factors are likely to be the first affected by a change in policies, legal charges, or market changes related to preventing or restoring damage to nature.

- On the other hand, companies are dependent on certain ecosystem services. For example, agricultural companies are dependent on ecosystem services such as water and pollination. Dependencies are mainly related to physical risk as companies with a high dependency will take the biggest hit from a disruption or decay of the ecosystem service caused by e.g. an oil spill or pests.

For banks, the impacts and dependencies of their own operations and of their counterparties can impact traditional financial (credit, liquidity, and market) and non-financial (operational and business) risks. In our biodiversity classification methodology, we assess both impacts and dependencies as indicators for physical and transition risk. This is further described in the next section.

Zanders’ biodiversity classification methodology

An important starting point for climate-related and environmental (C&E) risk management is the risk identification and materiality assessment. For C&E risks, and biodiversity in particular, obtaining data is a challenge. A quantitative assessment of materiality is therefore difficult to achieve. To address this, Zanders has developed a data driven classification methodology. By classifying the biodiversity impact and dependencies of exposures based on the sector and location of the counterparty, scores that quantify the portfolio’s physical and transition risks related to biodiversity are calculated. These scores are based on the databases of Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure (ENCORE) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).

Sector classification

The sector classification methodology is developed based on the ENCORE database. ENCORE is a public database that is recognized by global initiatives such as Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) and Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials (PBAF). ENCORE is a key tool for the “Evaluate” phase of the TNFD LEAP approach (Locate, Evaluate, Assess and Prepare).

ENCORE was developed specifically for financial institutions with the goal to assist them in performing a high-level but data-driven scan of their exposures’ impacts and dependencies. The scanning is made across multiple dimensions of the ecosystem, including biodiversity-related environmental drivers. ENCORE evaluates the potential reliance on ecosystem services2 and the changes of impacts drivers3 on natural capital assets4. It does so by assigning scores to different levels of a sector classification (sector, subindustry and production process). These scores are assigned for 11 impact drivers and 21 ecosystem services. ENCORE provides a score ranging from Very Low to Very High for a broad range of production processes, sub-sectors and sectors.

To compute the sector scores, ENCORE does not offer a methodology for aggregating scores for impacts drivers and ecosystem services. Therefore, ENCORE does not provide an overall dependency and impact per sector, sub-industry, or production process. However, Zanders has created a methodology to calculate a final aggregated impact and dependency score. The result of this aggregation is a single impact and a single dependency score for each ENCORE sector, sub-industry or production process. In addition, an overall impacts and dependencies scores are computed for the portfolio, based on its sector distribution. In both cases, scores range from 0 (no impact/dependency) to 5 (very high impact or dependency).

Location classification

The location scoring methodology is developed based on the WWF Biodiversity Risk Filter (hereafter called WWF BRF).5 The WWF BRF is a public tool that supports a location-specific analysis of physical- and transition-related biodiversity risks.

The WWF BRF consists of a set of 33 biodiversity indicators: 20 related to physical risks and 13 related to reputational risks, which are provided at country, but also on a more granular regional level. These indicators are aggregated by the tool itself, which ultimately provides one single scape physical risk and scape reputational risk per location.

To compute overall location scores, the WWF BRF does not offer a methodology for aggregating scores for countries and determine the overall transition risk (based on the scape reputational risk scores) and physical risk (based on the scape physical risk scores). However, Zanders has created a methodology to calculate a final aggregated transition and physical risk score for the portfolio, based on its geographical distribution. The result of this aggregation is a single transition and physical risk score for the portfolio, ranging from 0 (no risk) to 5 (very high risk).

Use case: RI&MA for biodiversity risks in a bank portfolio

In this section, we present a use case of classifying biodiversity risks for the portfolio of a fictional financial institution, using the sector and location scoring methodologies developed by Zanders.

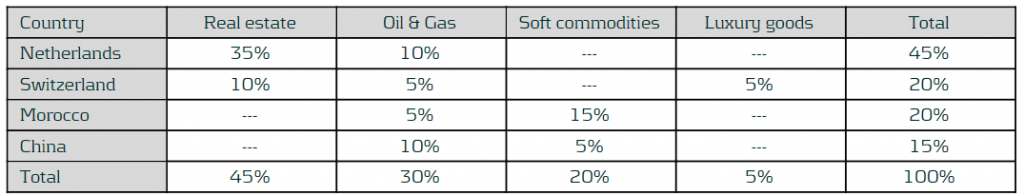

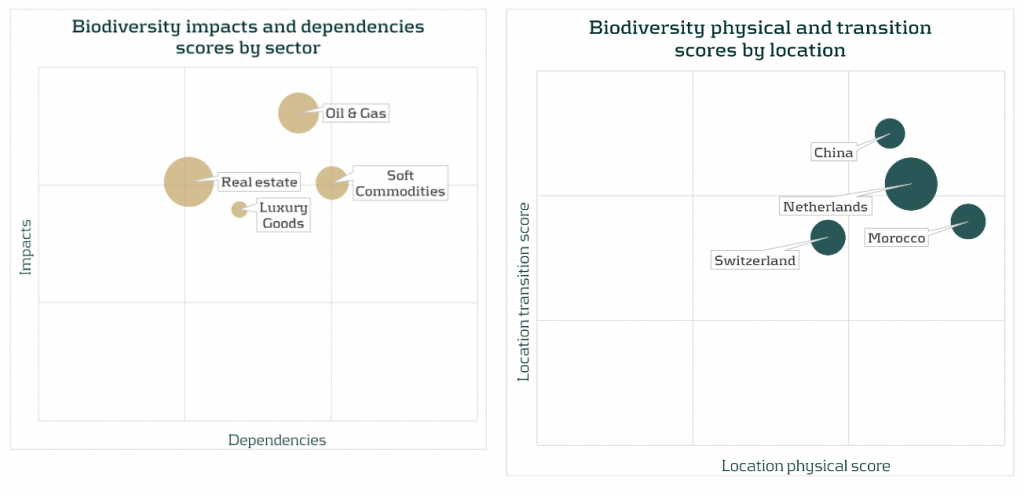

The exposures of this financial institution are concentrated in four sectors: Real estate, Oil & Gas, Soft commodities and Luxury goods. Moreover, the operations of these sectors are located across four different countries: the Netherlands, Switzerland, Morocco and China. The following matrix shows the percentage of exposures of the financial institution for each combination of sector and country:

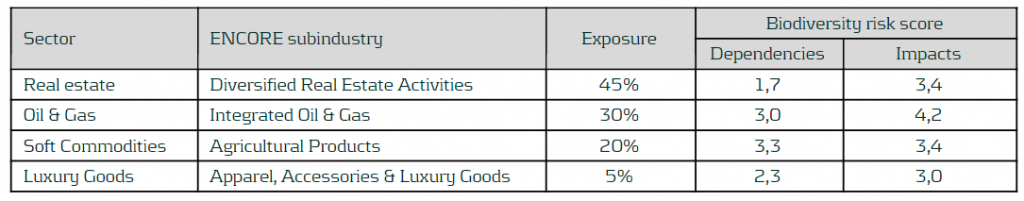

ENCORE provides scores for 11 ecosystem services and 21 impacts drivers. Those related to biodiversity risks are transformed to a range from 0 to 5. After that, biodiversity ecosystem services and biodiversity impacts drivers are aggregated into an overall biodiversity impacts and dependencies scores, respectively. The following table shows the mapping between the sectors in the portfolio and the corresponding sub-industry in the ENCORE database, including the aggregated biodiversity impacts and dependencies scores computed for those sub-industries. The mapping is done at sub-industry level, since it is the level of granularity of the ENCORE sector classification that better fits the sectors defined in the fictional portfolio. In addition, the overall impacts and dependencies scores are computed, by taking the weighted average sized by the sector distribution of the portfolio. This leads to scores of 3.8 and 2.4 for the impacts and dependencies scores, respectively.

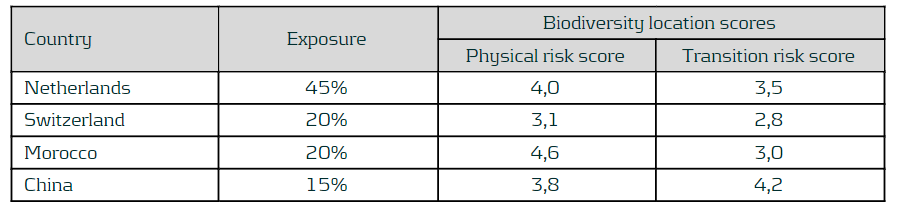

The WWF BRF provides biodiversity indicators at country level. It already provides an aggregated score for physical risk (namely, scape physical score) and for transition risk (namely, scape reputational risk score), so no further aggregation is needed. Therefore, the corresponding scores for the four countries within the bank portfolio are selected. As the last step, the location scores are transformed to a range similar to the sector scores, i.e., from 0 (no physical/transition risk) to 5 (very high physical/transition risk). The results are shown in the following table. In addition, the overall impacts and dependencies scores are computed, by taking the weighted average sized by the geographical distribution of the portfolio. This leads to scores of 3.9 and 3.3 for the physical and transition risk scores, respectively.

Results of the sector and location scores can be displayed for a better understanding and to enable comparison between sectors and countries. Bubble charts, such as the ones show below, present the sectors and location scores together with the size of the exposures in the portfolio (by the size of each bubble).

Combined with the size of the exposures, the results suggest that biodiversity-related physical and transition risks could result in financial risks for Soft commodities and Oil & Gas. This is due to high impacts and dependencies and their relevant size in the portfolio. Moreover, despite a low dependencies score, biodiversity risks could also impact the Real estate sector due to a combination of its high impact score and the high sector concentration (45% of the portfolio). From a location perspective, exposures located in China could face high biodiversity transition risks, while exposures located in Morocco are the most vulnerable to biodiversity physical risks. In addition, relatively high scores for both physical and transition risk scores for Netherlands, combined with the large size of these exposures in the portfolio, could also lead to additional financial risk.’

These results, combined with other information such as loan maturities, identified transmission channels, or expert inputs, can be used to inform the materiality of biodiversity risks.

Conclusion

Assessing the materiality of biodiversity risks is crucial for financial institutions in order to understand the risks and opportunities in their loan portfolios. In this article, Zanders has presented its approach for an initial quantification of biodiversity risks. Curious to learn how Zanders can support your financial institutions with the identification and quantification of biodiversity risks and the integration into the risk frameworks? Please reach out to Marije Wiersma, Iryna Fedenko or Miguel Manzanares.

Citations

- https://zandersgroup.com/en/insights/blog/biodiversity-risks-and-opportunities-for-financial-institutions-explained ↩︎

- In accordance with ENCORE, ecosystem services are the links between nature and business. Each of these services represent a benefit that nature provides to enable or facilitate business production processes. ↩︎

- In accordance with ENCORE AND Natural Capital Protocol (2016), an impacts driver is a measurable quantity of a natural resource that is used as an input to production or a measurable non-product output of business activity. ↩︎

- In accordance with ENCORE, natural capital assets are specific elements within nature that provide the goods and services that the economy depends on. ↩︎

- The WWF also provides a similar tool, the WWF Water Risk Filter, which could be used as to assess specific water-related environmental risks. ↩︎

EBA publishes recommendations how to include E&S risks in the prudential framework for banks and insurers.

In October 2023, the European Banking Authority (EBA) published a report[1] with recommendations for enhancements to the Pillar 1 prudential framework to reflect environmental and social (E&S) risks, distinguishing between actions to be taken in the short term and in the medium to long term. The short-term actions are to be taken into account over the next three years as part of the implementation of the revised Capital Requirements Regulation and Capital Requirements Directive (CRR3/CRD6).

The EBA report follows a discussion paper on the same topic from May 2022[2], on which it solicited input from the financial industry. In this note, we provide an overview of the recommended actions by the EBA that relate to the prudential framework for banks. The EBA report also contains recommended actions for the prudential framework applying to investment firms, but these are not addressed here.

If the EBA’s recommendations are implemented in the prudential framework, in our view the most immediate implications for banks would be:

- When using external ratings to determine own fund requirements for credit risk under the standardized approach (SA) of Pillar 1, ensure that E&S risks are explicitly considered when evaluating the appropriateness of the external ratings as part of the due diligence requirements.

- When calculating own fund requirements for credit risk under the internal-ratings-based (IRB) approach, embed E&S risks in the rating assignment, risk quantification (for example through a margin of conservatism or the downturn component) and/or expert judgment and overrides.

- To assess E&S risks at a borrower level, establish a process to obtain and update material E&S-related information on the borrowers’ financial condition and credit facility characteristics, as part of due diligence during onboarding and ongoing monitoring of the borrowers’ risk profile.

- For IRB banks, embed E&S risks in the credit risk stress testing programs.

- Ensure that E&S risks are considered in the valuation of collateral, specifically for financial and real estate collateral.

- For market risk, embed environmental risks in trading book risk appetite, internal trading limits and the new product approval process. Furthermore, for banks aiming to use the internal model approach (IMA) of the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) regulation, environmental risks need to be considered in their stress testing program.

- For operational risk, identify whether E&S risks constitute triggers of operational risk losses.

We note that many of these implications align with the ECB’s expectations in the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks[3].

Background

The EBA report considers both environmental and social risks, which the EBA characterizes as follows:

- As drivers of environmental risks, EBA distinguishes physical and transition (climate) risks. It does not explicitly refer in the report to other environmental risks, such as a loss of biodiversity or pollution, but in an earlier report the EBA considered these as part of chronic physical risks[4].

- EBA considers social factors to be related to the rights, well-being and interests of people and communities, including factors such as decent work, adequate living standards, inclusive and sustainable communities and societies, and human rights. As drivers of social risks, EBA distinguishes environmental factors (as materialization of physical and transition risks may change living standards and the labor market and increase social tensions, for example) as well as changes in policies and market sentiment. These may in part be driven by actions taken to meet the United Nation’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) in 2030.

In line with the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks[5], the EBA does not view E&S risks as stand-alone risks, but as drivers of traditional banking risks. This is depicted in Figure 1. The report considers the impact on credit, market, operational, liquidity and concentration risks and reviews to what extent E&S risks can be reflected in capital buffers and the macro-prudential framework. It does not explicitly consider the securitization framework, although this will be implicitly affected by impacts on credit risk. The EBA does not see an impact of E&S risks on the (risk-insensitive) leverage ratio, and therefore does not consider it in the report.

Figure 1: Examples of transmission channels for environmental and social risks (source: EBA).

The EBA notes that the Pillar 1 framework has been designed to capture the possible financial impact of cyclical economic fluctuations, but not to capture the manifestation of long-term environmental risks. It is therefore important to keep the main principles that form the basis of the prudential framework in mind when contemplating adjustments to reflect E&S risks in the prudential framework. The main principles as highlighted by the EBA are summarized below.

Main principles of the prudential framework and the relation to the horizon for E&S risks

With repect to the framework in general:

- Own fund requirements are intended to cover potential unexpected losses. In contrast, expected losses are directly deducted from own funds, and are generally captured in the accounting rules through provisions, impairments, write-downs and appropriate valuation of assets.

- The purpose of own fund requirements is to ensure resilience of an institution to unexpected adverse circumstances, before appropriate mitigating actions and strategy adjustments can be implemented. Therefore, environmental factors that can affect institutions in the short to medium term are expected to be reflected in the prudential framework. However, for those with an impact in the longer term, institutions are expected to take appropriate mitigating actions in their strategy.

- The high confidence level used in the Pillar 1 framework to protect institutions from risks over the short to medium horizon may no longer be achievable and appropriate if longer horizons would be considered.

- To the extent that institutions are exposed to E&S risks in relation to their specific strategy and business model, coverage of these risks in the Pillar 2 own-fund requirements instead of Pillar 1 could be appropriate. In addition, reflection of these risks in the Pillar 2 guidance for stress testing may be considered.

With respect to the internal-ratings-based (IRB) approach for credit risk:

- The Probability of Default (PD) represents a one-year default probability, which is required to be calibrated based on long-run average (‘through-the-cycle’) default rates. As such, longer-term risk characteristics of the obligor may be taken into account.

- The Credit Conversion Factor (CCF) as an estimate of potential additional drawdowns before default naturally relates to the one-year time horizon for the PD, but is expected to reflect the situation of an economic downturn.

- The time horizon for the Loss Given Default (LGD) extends to the full maturity of the exposure and/or the collection process and its calibration is also expected to reflect the situation of an economic downturn.

In the following sections we summarize the EBA recommendations by risk type.

Credit risk

The recommendations of the EBA largely put the burden on financial institutions to take E&S risks into account in the inputs for the existing Pillar 1 framework and/or to apply conservatism or overrides to the outputs. It does not recommend to include explicit E&S risk-related elements in the determination of risk weights for rated and unrated exposures in the SA or in the risk-weight formulas of the IRB. The main reasons for not doing so are that it is not clear what common and objective E&S-related factors should be used as input, what the proper functional form would be, a lack of evidence on which the size of an adjustment could be based so that it results in proper risk differentiation, and the risk of double counting with the reflection of E&S risks in the inputs to the existing own funds calculations under Pillar 1 (external ratings in the SA and PD, LGD and CCF in the case of IRB). However, the EBA will continue to evaluate this possibility in the medium to long term. The EBA also does not recommend introducing an environment-related adjustment factor to the risk weights resulting from the existing Pillar 1 framework[6].

Recommended actions for credit risk

| Short term |

- SA) The EBA encourages rating agencies to integrate environmental and social factors as drivers in the external credit risk assessments and to provide enhanced disclosures and transparency about the rating methodologies.

- (SA) Financial institutions to explicitly consider environmental factors in the due diligence that they are required to perform when using external credit risk assessments.

- (IRB) Financial institutions to reflect E&S risks in the rating assignment, risk quantification (for example through a margin of conservatism or the downturn component) and/or expert judgment and overrides, without affecting the overall performance of the rating system. In this context:

- Quantification of risks must be based on sufficient and reliable observations;

- Overrides should be for specific, individual cases where the institution believes there is material exposure to E&S risks but it has insufficient information to quantify it. Such overrides need to be regularly assessed and challenged;

- If an institution derives PDs for internal rating grades by a mapping to a scale from a credit rating institution, it needs to consider whether the default rates associated with the external scale reflect material E&S risks.

- To assess E&S risks at a borrower level, institutions need to have a process to obtain and update material E&S-related information on the borrowers’ financial condition and on credit facility characteristics, as part of the due diligence during onboarding and ongoing monitoring of borrowers’ risk profile.

- (IRB) Financial institutions to consider E&S risks in their stress testing programs.

- (SA, IRB) Financial institutions to ensure prudent valuation of immovable property collateral, considering climate-related physical and transition risks as well as other environmental risks. The prudent valuation should be considered at origination, re-valuation and during monitoring.

| Medium to long term |

- (SA) Financial institutions to monitor that environmental factors are reflected in financial collateral valuations through market values under Pillar 1 and valuation methodologies under Pillar 2.

- (SA) The EBA to consider whether benefits from the Infrastructure Supporting Factor (ISF) should only be applied to high-quality specialized lending corporate exposures that meet strong environmental standards.

- (SA) The EBA to consider adjusting risk weights, both in general and specifically for those assigned to real estate exposures.

- (IRB) As E&S risks materialize in defaults and loss rates over time, institutions need to redevelop or recalibrate their PD and LGD estimates.

(SA = standardized approach; IRB = Internal-rating-based approach)

Market risk

Within market risk, the EBA sees the main interaction of E&S risks with the equity, credit spread and commodity markets, in which E&S risks may cause additional volatility. In line with the existing regulatory guidance, the EBA expects E&S risks not to be treated as separate risk factors but as drivers of existing risk factors, with the exception of products for which cash flows depend specifically on ESG factors (‘ESG-linked products’).

The EBA does not recommend changes at this point to the standardized approach (SA) and the internal model approach (IMA) under the FRTB regulation, which will come into effect in the EU in 2025. The primary reason is the lack of sufficient evidence on the impact of E&S risks to enable a data driven approach, which forms the basis of the FRTB.

When calculating the expected shortfall (ES) measure under the IMA based on last 12 months' market data, the materialization of E&S risks will automatically be reflected in the market data that is used. When using market data from a stress period, either to calculate ES in the IMA or to calibrate risk factor shocks for the sensitivity-based measure (SbM) at a risk class level in the SA, the reflection of E&S risks will depend on the choice of stress period. To include E&S risks fully in the IMA but avoid overlap with the (partial) presence of E&S risks in historical data, the EBA views the consideration of E&S risks in a separate ‘risk not in the model engine’ (RNIME) add-on as most promising option for the medium to long term, leveraging the framework described in the ECB Guide to internal models[7].

Recommended actions for market risk

| Short term |

- (SA, IMA) Financial institutions to consider environmental risks in relation to their trading book risk appetite, internal trading limits and new product approval.

- (IMA) Financial institutions to consider environmental risk as part of their stress testing program that is required to get internal model approval.

| Medium to long term |

- (SA, IMA) Competent authorities to consider how to treat ESG-linked products for the residual risk add-on in the SA and in the IMA.(SA) The EBA to consider including a dimension for ESG risks in the existing equity and credit spread risk classes, or including a separate environmental risk class.

- (IMA) Financial institutions to consider ESG risks when monitoring risks that are not included in the model, for which the ECB’s RNIME framework could be used as a basis.

(SA = standardized approach; IRB = Internal-rating-based approach)

Operational risk

The EBA notes that various types of operational risks can increase as a result of E&S risks, including damage to physical assets, disruption of business processes and litigation. However, the new standardized approach (SA) for operational risk in the Basel III framework, which will come into effect in the EU in 2025, does not have a forward-looking component – it only considers historical loss experience (besides business indicators). Historical losses are unlikely to fully reflect the potential future impact of E&S risks, but there is as of yet insufficient evidence and data to quantify and consider this in an amendment of the SA.

Recommended actions for operational risk

| Short term |

- Financial institutions to identify whether E&S risks constitute triggers of operational risk losses.

| Medium to long term |

- Following evidence of E&S risk factors to trigger operational risk losses, the EBA to consider whether revisions to the BCBS SA methodology are warranted.

Liquidity risk

The EBA report describes three ways in which E&S risks may affect the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) calculation. First, liquid assets that are specifically exposed to E&S risks may become less liquid and/or decrease in value. As a consequence, they may no longer satisfy the eligibility criteria for liquid assets. If they still do, then the decrease in market value would reflect the lower liquidity and reduce the LCR. Second, contingent liabilities arising from environmentally harmful investments would need to be included as outflows in the LCR calculation, thereby lowering the LCR. Third, a decrease in credit quality of receivables that are particularly exposed to E&S risks will decrease the inflows that can be taken into account in the LCR calculation. The EBA concludes that the existing LCR framework can capture the impact of E&S risks on the definition of liquid assets, outflows and inflows, so that no amendments are needed.

Regarding the existing framework for the net stable funding ratio (NSFR), the EBA notes that a reduction in the creditworthiness and/or liquidity of loans and securities exposed to E&S risks would lead to a higher requirement for stable funding and thereby negatively impact the NSFR. In this way, the existing NSFR framework can capture the impact of E&S risks on the definition of stable assets.

In summary, the EBA does not propose changes to the LCR and NSFR frameworks in relation to E&S risks. In case of excessive exposure to E&S risks for individual institutions, it notes that supervisors can set specific liquidity or funding requirements as part of the Pillar 2 framework for LCR and NSFR.

Concentration risk

The SA and IRB of the Pillar 1 framework for credit risk assume that a bank’s loan portfolio has full diversification of name-specific (idiosyncratic) risk and is well diversified across sectors and geographies. Because of these assumptions, the framework is not able to capture concentration risks, including those arising from E&S risks. In the current framework, single-name concentration risk is separately captured in Pillar 1 using the large exposure regime. Sector and geographic concentrations are considered in the SREP process under Pillar 2.

Recommended actions for concentration risk

| Short term |

- The EBA to develop a definition of environment-related concentration risk as well as exposure-based metrics for its quantification (e.g., ratio of exposures sensitive to a given environmental risk driver in a specific geographical area or in a specific industry sector over total exposures, total capital or RWA). These metrics will be part of supervisory reporting and, when relevant, external disclosure. In addition, they should be considered as part of Pillar 2 under SREP and/or supplement Pillar 3 disclosures on ESG risks.The EBA does not recommend to change the existing large exposure regime.

| Medium to long term |

- Based on the experience obtained with initial environment-related concentration risk metrics and quantification, the EBA may consider enhanced metrics and the appropriateness to introduce it in the Pillar 1 framework.

- This would entail the design and calibration of possible limits and thresholds, add-ons or buffers, as well as the specification of possible consequences if there are breaches.

Capital buffers and macroprudential framework

An alternative to amending the calculation of capital requirements to capture E&S risks in the prudential framework would be to increase the minimum required level of capital and/or to implement ‘borrower-based measures’ (BMM). Such BMMs aim to prevent a build-up of risk concentrations, for example by setting upper bounds on loan-to-value or loan-to-income for mortgage lending. Of the various possibilities, the EBA deems the use of a systemic risk capital buffer as the most suitable, although a double counting with the inclusion of E&S risks in the calculation of capital requirements under Pillar 1 and 2 needs to be avoided.

Recommended actions for capital buffers and macroprudential framework

| Short term |

- The EBA to asses changes to the guidelines on the appropriate subsets of sectoral exposures to which a systematic risk buffer may be applied.

| Medium to long term |

- The EBA to coordinate with other ongoing initiatives and assess the most appropriate adjustments.

Conclusion

The EBA considers E&S risks as a new source of systemic risk, which may not be adequately captured in the existing prudential framework. At the same time, the EBA recognizes the challenges in assessing the impact of these risks on regulatory metrics. The challenges range from a lack of granular and comparable data, varying definitions of what is environmentally and socially sustainable, historic data not being representative of what can be expected in the future, to the high uncertainty about the probability of future materialization of E&S risks. Moreover, the time horizon considered in the existing Pillar 1 framework is much shorter than the long horizon over which environmental risks are likely to fully materialize, with an exception of short-term acute physical and transition risks.

Against this background, the EBA does not recommend concrete quantitative adjustments to the existing Pillar 1 framework at this point. Nonetheless, it does expect financial institutions to take E&S risks into account in the inputs to the existing Pillar 1 framework or to apply overrides based on expert judgment. The EBA further proposes actions that should provide more clarity over time about the drivers and materiality of E&S risks. In due time, this can provide the basis for quantitative amendments to the Pillar 1 framework.

If you are interested to discuss this topic in more detail or would like support to embed E&S risks in your organization, please contact Pieter Klaassen at [email protected] or +41 78 652 5505.

[1]EBA (2023), Report on the role of environmental and social risks in the prudential framework (link), October.

[2] EBA (2022), Discussion paper on the role of environmental risks in the prudential framework (link), May. For a summary, see the article (link) on the Zanders website.

[3] ECB (2020), Guide on climate-related and environmental risks (link), November.

[4] See section 2.3.2 in EBA (2021), Report on management and supervision of ESG risks for credit institutions and investment firms (link), June.

[5] ECB (2020), Guide on climate-related and environmental risks (link), November.

[6] In the current EU Pillar 1 framework, adjustments are included that result in lower risk weights for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME) and infrastructure lending. As the EBA notes, these adjustments are not risk-based but have been included in the EU to support lending to SMEs and for infrastructure projects.

The 2023 Global Risk Report by the World Economic Forum investigates the potential hazards for humanity in the next decade.

In this report, biodiversity loss ranks as the fourth most pressing concern after climate change adaptation, mitigation failure, and natural disasters. For financial institutions (FIs), it is therefore a relevant risk that should be taken into account. So, how should FIs implement biodiversity risk in their risk management framework?

Despite an increasing awareness of the importance of biodiversity, human activities continue to significantly alter the ecosystems we depend on. The present rate of species going extinct is 10 to 100 times higher than the average observed over the past 10 million years, according to Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials[i]. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) reports that 75% of ecosystems have been modified by human actions, with 20% of terrestrial biomass lost, 25% under threat, and a projection of 1 million species facing extinction unless immediate action is taken. Resilience theory and planetary boundaries state that once a certain critical threshold is surpassed, the rate of change enters an exponential trajectory, leading to irreversible changes, and, as noted in a report by the Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), we are already close to that threshold[ii].

We will now explain biodiversity as a concept, why it is a significant risk for financial institutions (FIs), and how to start thinking about implementing biodiversity risk in a financial institutions’ risk management framework.

What is biodiversity?

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) defines biodiversity as “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, i.a., terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part.”[iii] Humans rely on ecosystems directly and indirectly as they provide us with resources, protection and services such as cleaning our air and water.

Biodiversity both affects and is affected by climate change. For example, ecosystems such as tropical forests and peatlands consist of a diverse wildlife and act as carbon sinks that reduce the pace of climate change. At the same time, ecosystems are threatened by the accelerating change caused by human-induced global warming. The IPBES and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in their first-ever collaboration, state that “biodiversity loss and climate change are both driven by human economic activities and mutually reinforce each other. Neither will be successfully resolved unless both are tackled together.”[iv]

Why is it relevant for financial institutions?

While financial institutions’ own operations do not materially impact biodiversity, they do have impact on biodiversity through their financing. ASN Bank, for instance, calculated that the net biodiversity impact of its financed exposure is equivalent to around 516 square kilometres of lost biodiversity – which is roughly equal to the size of the isle of Ibiza in Spain[v]. The FIs’ impact on biodiversity also leads to opportunities. The Institute Financing Nature (IFN) report estimates that the financing gap for biodiversity is close to $700 billion annually[vi]. This emphasizes the importance of directing substantial financial resources towards biodiversity-positive initiatives.

At the same time, biodiversity loss also poses risks to financial institutions.

The global economy highly depends on biodiversity as a result of the increasedglobalization and interconnectedness of the financial system. Due to these factors, the effects of biodiversity losses are magnified and exacerbated through the financial system, which can result in significant financial losses. For example, approximately USD 44 trillion of the global GDP is highly or moderately dependent on nature (World Economic Forum, 2020). Specifically for financial institutions, the DNB estimated that Dutch FIs alone have EUR 510 billionof exposure to companies that are highly or very highly dependent on one or more ecosystems services[vii]. Furthermore, in the 2010 World Economic Forum report worldwide economic damage from biodiversity loss is estimated to be around USD 2 to 4.5 trillion annually. This is remarkably high when compared to the negative global financial damage of USD 1.7 trillion per year from greenhouse gas emissions (based on 2008 data), which demonstrates that institutions should not focus their attention solely on the effects of climate change when assessing climate & environmental risks[viii].

Examples of financial impact

Similarly to climate risk, biodiversity risk is expected to materialize through the traditional risk types a financial institution faces. To illustrate how biodiversity loss can affect individual financial institutions, we provide an example of the potential impact of physical biodiversity risk on, respectively, the credit risk and market risk of an institution:

Credit risk:

Failing ecosystem services can lead to disruptions of production, reducing the profits of counterparties. As a result, there is an increase in credit risk of these counterparties. For example, these disruptions can materialize in the following ways:

- A total of 75% of the global food crop rely on animals for their pollination. For the agricultural sector, deterioration or loss of pollinating species may result in significant crop yield reduction.

- Marine ecosystems are a natural defence against natural hazards. Wetlands prevented USD 650 million worth of damages during the 2012 Superstorm Sandy [OECD, 2019), while the material damage of hurricane Katrina would have been USD 150 billion less if the wetlands had not been lost.

Market risk:

The market value of investments of a financial institution can suffer from the interconnectedness of the global economy and concentration of production when a climate event happens. For example:

- A 2011 flood in Thailand impacted an area where most of the world's hard drives are manufactured. This led to a 20%-40% rise in global prices of the product[ix]. The impact of the local ecosystems for these type of products expose the dependency for investors as well as society as a whole.

Core part of the European Green Deal

The examples above are physical biodiversity risk examples. In addition to physical risk, biodiversity loss can also lead to transition risk – changes in the regulatory environment could imply less viable business models and an increase in costs, which will potentially affect the profitability and risk profile of financial institutions. While physical risk can be argued to materialize in a more distant future, transition risk is a more pressing concern as new measures have been released, for example by the European Commission, to transition to more sustainable and biodiversity friendly practices. These measures are included in the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030 and the EU’s Nature restoration law.

The EU’s biodiversity strategy for 2030 is a core part of European Green Deal. It is a comprehensive, ambitious, and long-term plan that focuses on protecting valuable or vulnerable ecosystems, restoring damaged ecosystems, financing transformation projects, and introducing accountability for nature-damaging activities. The strategy aims to put Europe's biodiversity on a path to recovery by 2030, and contains specific actions and commitments. The EU biodiversity strategy covers various aspects such as:

- Legal protection of an additional 4% of land area (up to a total of 7%) and 19% of sea area (up to a total of 30%)

- Strict protection of 9% of sea and 7% of land area (up to a total of 10% for both)

- Reduction of fertilizer use by at least 20%

- Setting measures for sustainable harvesting of marine resources

A major step forwards towards enforcement of the strategy is the approval of the Nature restoration law by the EU in July 2023, which will become the first continent-wide comprehensive law on biodiversity and ecosystems. The law is likely to impact the agricultural sector, as the bill allows for 30% of all former peatlands that are currently exploited for agriculture to be restored or partially shifted to other uses by 2030. By 2050, this should be at least 70%. These regulatory actions are expected to have a positive impact on biodiversity in the EU. However, a swift implementation may increase transition risk for companies that are affected by the regulation.

The ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks explicitly states that biodiversity loss is one of the risk drivers for financial institutions[x]. Furthermore, the ECB Guide requires financial institutions to asses both physical and transition risks stemming from biodiversity loss. In addition, the EBA Report on the Management and Supervision of ESG Risk for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms repeatedly refers to biodiversity when discussing physical and transition risks[xi].

Moreover, the topic ‘biodiversity and ecosystems’ is also covered by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which requires companies within its scope to disclose on several sustainability related matters using a double materiality perspective.[1] Biodiversity and ecosystems is one of five environmental sustainability matters covered by CSRD. At a minimum, financial institutions in scope of CSRD must perform a materiality assessment of impacts, risks and opportunities stemming from biodiversity and ecosystems. Furthermore, when biodiversity is assessed to be material, either from financial or impact materiality perspective, the institution is subject to granular biodiversity-related disclosure requirements covering, among others, topics such as business strategy, policies, actions, targets, and metrics.

Where to start?

In line with regulatory requirements, financial institutions should already be integrating biodiversity into their risk management practices. Zanders recognizes the challenges associated with biodiversity-related risk management, such as data availability and multidimensionality. Therefore, Zanders suggests to initiate this process by starting with the following two steps. The complexity of the methodologies can increase over time as the institution’s, the regulator’s and the market’s knowledge on biodiversity-related risks becomes more mature.

- Perform materiality assessment using the double materiality concept. This means that financial institutions should measure and analyze biodiversity-related financial materiality through the identification of risks and opportunities. Institutions should also assess their impacts on biodiversity, for example, through calculation of their biodiversity footprint. This can start with classifying exposures’ impact and dependency on biodiversity based on a sector-level analysis.

- Integrate biodiversity-related risks considerations into their business strategy and risk management frameworks. From a business perspective, if material, financial institutions are expected to integrate biodiversity in their business strategy, and set policies and targets to manage the risks. Such actions could be engagement with clients to promote their sustainability practices, allocation of financing to ‘biodiversity-friendly’ projects, and/or development of biodiversity specific products. Moreover, institutions are expected to adjust their risk appetites to account for biodiversity-related risks and opportunities, establish KRIs along with limits and thresholds. Embedding material ESG risks in the risk appetite frameworks should include a description on how risk indicators and limits are allocated within the banking group, business lines and branches.

Considering the potential impact of biodiversity loss on financial institutions, it is crucial for them to extend their focus beyond climate change and also start assessing and managing biodiversity risks. Zanders can support financial institutions in measuring biodiversity-related risks and taking first steps in integrating these risks into risk frameworks. Curious to hear more on this? Please reach out to Marije Wiersma, Iryna Fedenko, or Jaap Gerrits.

[1] CSRD applies to large EU companies, including banks and insurance firms. The first companies subject to CSRD must disclose according to the requirements in the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) from 2025 (over financial year 2024), and by the reporting year 2029, the majority of European companies will be subject to publishing the CSRD reports. The sustainability report should be a publicly available statement with information on the sustainability-matters that the company considers material. This statement needs to be audited with limited assurance.

[i] PBAF. (2023). Dependencies - Pertnership for Biodiversity Acccounting Financials (PBAF)

[ii] De Nederlandche Bank. (2020). Indepted to nature - Exploring biodiversity risks for the Dutch Financial Sector.

[iii] CBD. (2005). Handbook of the convention on biological diversity

[iv] IPBES. (2021). Tackling Biodiversity & Climate Crises Together & Their Combined Social Impacts

[v] ASN Bank (2022). ASN Bank Biodiversity Footprint

[vi] Paulson Institute. (2021). Financing nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity

[vii] De Nederlandche Bank. (2020). Indepted to nature - Exploring biodiversity risks for the Dutch Financial Sector

[viii] PwC for World Economic Forum. (2010). Biodiversity and business risk

[ix] All the examples related to credit and market risk are presented in the report by De Nederlandsche Bank. (2020). Biodiversity Opportunities and Risks for the Financial Sector

[x] ECB. (2020). Guide on climate-related and environmental risks.

[xi] EBA. (2021). EBA Report on Management and Supervision of ESG Risk for Credit Institutions and Investment Firms