IFRS 17: the impact of the building blocks approach

On 18 May 2017, the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) issued the new IFRS 17 standards. The development of these standards has been a long and thorough process with the aim of providing a single global comprehensive accounting standard for insurance contracts.

The new standards will have a significant impact on the measurement and presentation of insurance contracts in the financial statements and require significant operational changes. This article takes a closer look at the new standards, and illustrates the impact with a case study.

The standard model, as defined by IFRS 17, of measuring the value of insurance contracts is the ‘building blocks approach’. In this approach, the value of the contract is measured as the sum of the following components:

- Block 1: Sum of the future cash flows that relate directly to the fulfilment of the contractual obligations.

- Block 2: Time value of the future cash flows. The discount rates used to determine the time value reflect the characteristics of the insurance contract.

- Block 3: Risk adjustment, representing the compensation that the insurer requires for bearing the uncertainty in the amount and timing of the cash flows.

- Block 4: Contractual service margin (CSM), representing the amount available for overhead and profit on the insurance contract. The purpose of the CSM is to prevent a gain at initiation of the contract.

Risk adjustment vs risk margin

IFRS 17 does not provide full guidance on how the risk adjustment should be calculated. In theory, the compensation required by the insurer for bearing the risk of the contract would be equal to the cost of the needed capital. As most insurers within the IFRS jurisdiction capitalize based on Solvency II (SII) standards, it is likely that they will leverage on their past experience. In fact, there are many similarities between the risk adjustment and the SII risk margin.

The risk margin represents the compensation required for non-hedgeable risks by a third party that would take over the insurance liabilities. However, in practice, this is calculated using the capital models of the insurer itself. Therefore, it seems likely that the risk margin and risk adjustment will align. Differences can be expected though. For example, SII allows insurers to include operational risk in the risk margin, while this is not allowed under IFRS 17.

Liability adequacy test

Determining the impact of IFRS 17 is not straightforward: the current IFRS accounting standard leaves a lot of flexibility to determine the reserve value for insurance liabilities (one of the reasons for introducing IFRS 17). The reserve value reported under current IFRS is usually grandfathered from earlier accounting standards, such as Dutch GAAP. In general, these reserves can be defined as the present value of future benefits, where the technical interest rate and the assumptions for mortality are locked-in at pricing.

However, insurers are required to perform liability adequacy testing (LAT), where they compare the reserve values with the future cash flows calculated with ‘market consistent’ assumptions. As part of the market consistent valuation, insurers are allowed to include a compensation for bearing risk, such as the risk adjustment. Therefore, the biggest impact on the reserve value is expected from the introduction of the CSM.

The IASB has defined a hierarchy for the approach to measure the CSM at transition date. The preferred method is the ‘full retrospective application’. Under this approach, the insurer is required to measure the insurance contract as if the standard had always applied. Hence, the value of the insurance contract needs to be determined at the date of initial recognition and consecutive changes need to be determined all the way to transition date. This process is outlined in the following case study.

A case study

The impact of the new IFRS standards is analyzed for the following policy:

- The policy covers the risk that a mortgage owner deceases before the maturity of the loan. If this event occurs, the policy pays the remaining notional of the loan.

- The mortgage is issued on 31 December 2015 and has an initial notional value of € 200,000 that is amortized in 20 years. The interest percentage is set at 3 per cent.

- The policy pays an annual premium of € 150. The annual estimated costs of the policy are equal to 10 per cent of the premium.

In the case of this policy, an insurer needs to capitalize for the risk that the policy holder’s life expectancy decreases and the risk that expenses will increase (e.g. due to higher than expected inflation). We assume that the insurer applies the SII standard formula, where the total capital is the sum of the capital for the individual risk types, based on 99.5 per cent VaR approach, taking diversification into account.

The cost of capital would then be calculated as follows:

- Capital for mortality risk is based on an increase of 15 per cent of the mortality rates.

- Capital for expense risk is based on an increase of 10 per cent in expense amount combined with an increase of 1 per cent in the inflation.

- The diversification between these risk types is assumed to be 25 per cent.

- Future capital levels are assumed to be equal to the current capital levels, scaled for the decrease in outstanding policies and insurance coverage.

- The cost-of-capital rate equals 6 per cent.

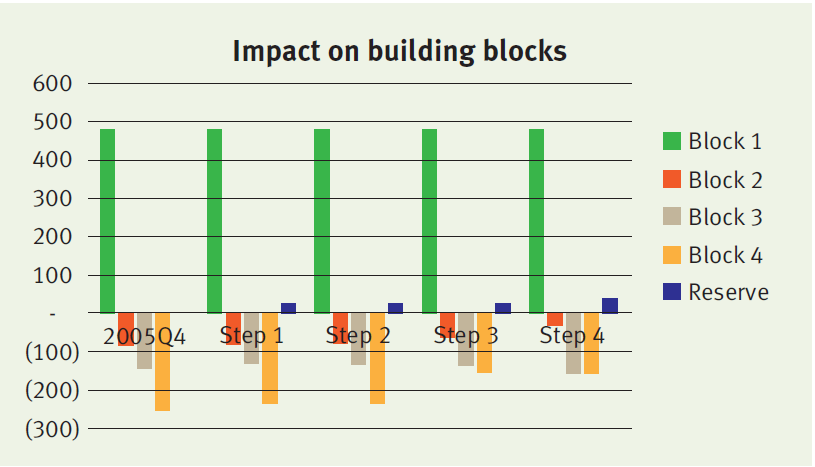

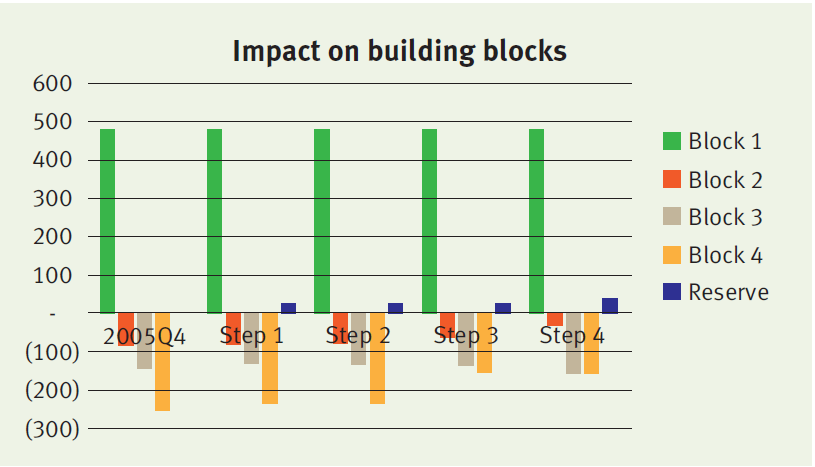

At initiation (i.e. 2015 Q4), the value of the contract under the new standards equals the sum of:

- Block 1: € 482

- Block 2: minus € 81

- Block 3: minus € 147

- Block 4: minus € 254

Consecutive changes

The insurer will measure the sum of blocks 1, 2 and 3 (which we refer to as the fulfilment cash flows) and the remaining amount of the CSM at each reporting date. The amounts typically change over time, in particular when expectations about future mortality and interest rates are updated. We distinguish four different factors that will lead to a change in the building blocks:

Step 1. Time effect

Over time, both the fulfilment cash flows and the CSM are fully amortized. The amortization profile of both components can be different, leading to a difference in the reserve value.

Step 2. Realized mortality is lower than expected

In our case study, the realized mortality is about 10 per cent lower than expected. This difference is recognized in P&L, leading to a higher profit in the first year. The effect on the fulfilment cash flows and CSM is limited. Consequently, the reserve value will remain roughly the same.

Step 3. Update of mortality assumptions

Updates of the mortality assumptions affect the fulfilment cash flows, which is simultaneously recognized in the CSM. The offset between the fulfilment cash flows and the CSM will lead to a very limited impact on the reserve value. In this case study, the update of the life table results in higher expected mortality and increased future cash outflows.

Step 4. Decrease in interest rates

Updates of the interest rate curve result in a change in the fulfilment cash flows. This change is not offset in the CSM, but is recognized in the other comprehensive income. Therefore a decrease in the discount curve will result in a significant change in the insurance liability. Our case study assumes a decrease in interest rates from 2 per cent to 1 per cent. As a result, the fulfilment cash flows increase, which is immediately reflected by an increase in the reserve value.

The impact of each step on the reserve value and underlying blocks is illustrated below.

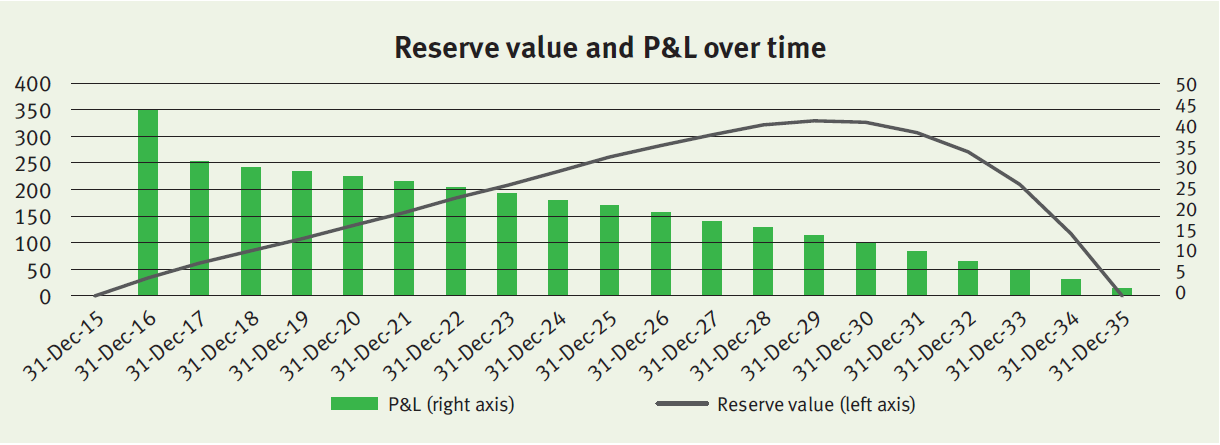

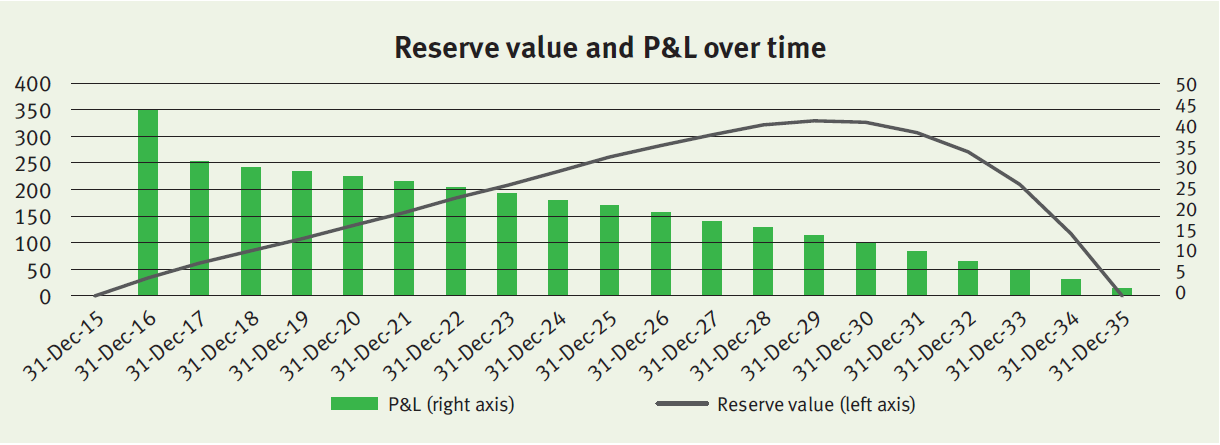

Onwards

The policy will evolve over time as expected, meaning that mortality will be realized as expected and discount rates do not change anymore. The reserve value and P&L over time will evolve as illustrated below.

The profit gradually decreases over time in line with the insurance coverage (i.e. outstanding notional of the mortgage). The relatively high profit in 2016 is (mainly) the result of the realized mortality that was lower than expected (step 2 described above).

As described before, under the full retrospective application, the insurer would be required to go all the way back to the initial recognition to measure the CSM and all consecutive changes. This would require insurers to deep-dive back into their policy administration systems. This has been acknowledged by the IASB by allowing insurers to implement the standards three years after final publication. Insurers will have to undertake a huge amount of operational effort and have already started with their impact analyses. In particular, the risk adjustment seems a challenging topic that requires an understanding of the capital models of the insurer.

Zanders can support in these qualitative analyses and can rely on its past experience with the implementation of Solvency II.

Hedge accounting changes under IFRS 9

On 18 May 2017, the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) issued the new IFRS 17 standards. The development of these standards has been a long and thorough process with the aim of providing a single global comprehensive accounting standard for insurance contracts.

Cross-currency interest rate swaps (CC-IRS), options, FX forwards and commodity trades are just a few examples of financial instruments which will be affected by the upcoming changes. The time value, forward points and cross-currency basis spread will receive different accounting treatment under IFRS 9. Within Zanders, we feel the need to clarify these key changes that deserve as much awareness as possible.

1. Accounting for the forward element in foreign currency forwards

Each FX forward contract possesses a spot and forward element. The forward element represents the interest rate differential between the two currencies. Under IFRS 9 (similar to IAS 39), it is allowed to designate the entire contract or just the spot component as the hedging instrument. When designating the spot component only, the change in fair value of the forward element is recognised in OCI and accumulated in a separate component of equity. Simultaneously, the fair value of the forward points at initial recognition is amortised, most expected linearly, over the life of the hedge.

Again, this accounting treatment is only allowed in case the critical terms are aligned (similar). If at inception the actual value of the forward element exceeds the aligned value, changes in the fair value based on the aligned item will go through OCI. The difference between the fair value of the actual and aligned forward elements is recognized in P&L. In case the value of the aligned forward element exceeds the actual value at inception, changes in fair value are based on the lower of aligned versus actual and go to OCI. The remaining change of actual will be recognized in P&L.

Please refer to the example below:

In this example, we consider an entity X which is hedging a future receivable with an FX forward contract.

MtM change of the forward = 105,000 (spot element) + 15,000 (forward element) = 120,000.

MtM change of the hedged item = 105,000 (spot element) + 5,000 (forward element) = 110,000.

We look at alternatives under IAS39 and IFRS9 that show different accounting methods depending on the separation between the spot and forward rates.

Under IAS39 and without a spot/forward separation, the hedging instrument represents the sum of the spot and the forward element (105 000 spot + 15 000 forward= 120 000). The hedged item consisting of 105 000 spot element and 5 000 forward element and the hedge ratio being within the boundaries, the minimum between the hedging instrument and hedged item is listed as OCI, and the difference between the hedging instrument and the hedged item goes to the P&L.

However, with the spot/forward separation under IAS39, the forward component is not included in the hedging relationship and is therefore taken straight to the P&L. Everything that exceeds the movement of the hedged item is considered as an “over hedge” and will be booked in P&L.

Line 3 and 4 under IFRS9 characterise comparable registration practices than under IAS39. The changes come in when we examine line 5, where the forward element of 5 000 can be registered as OCI. In this case, a test on both the spot and the forward element is performed, compared to the previous line where only one test takes place.

2. Rebalancing in a commodity hedge relation

Under influence of changing economic circumstances, it could be necessary to change the hedge ratio, i.e. the ratio between the amount of hedged item and the amount of hedging instruments. Under IAS 39, changes to a hedge ratio require the entity to discontinue hedge accounting and restart with a new hedging relationship that captures the desired changes. The IFRS 9 hedge accounting model allows you to refine your hedge ratio without having to discontinue the hedge relationship. This can be achieved by rebalancing.

Rebalancing is possible if there is a situation where the change in the relationship of the hedging instrument and the hedged item can be compensated by adjusting the hedge ratio. The hedge ratio can be adjusted by increasing or decreasing either the number of designated hedging instruments or hedged items.

When rebalancing a hedging relationship, an entity must update its documentation of the analysis of the sources of hedge ineffectiveness that are expected to affect the hedging relationship during its remaining term.

Please refer to the example below:

Entity X is hedging a forecast receivable with a FX call.

MtM change of the option = 100,000 (intrinsic value) + 40,000 (time value) = 140,000.

MtM change of the hedged item = 100,000 (intrinsic value) + 30,000 (time value) = 130,000.

In example 3, we consider entity X to be hedging a forecast receivable via an FX call. Note that under IAS39 the hedged item cannot contain an optionality if this optionality is not present in the underlying exposure. Hence, in this example, the hedged item cannot contain any time value. The time value of 30,000 can be used under IFRS9, but only by means of a separate test (see row 5).

In line 1, we can see that without a time-intrinsic separation, the hedge relationship is no longer within the 80-125% boundary; therefore, it needs to be discontinued and the full MtM has to be booked in the P&L. In line 2, there is a time-intrinsic separation, and the 40 000 representing the time value of the option are not included in the hedge relationship, meaning that they go straight to the P&L.

Under IFRS9 with no time-intrinsic separation (line 3), the hedging relationship is accounted for in the usual manner, as the ineffectiveness boundary is not applicable, with 100 000 going representing OCI, and the over hedged 40 000 going to the P&L.

However, the time-intrinsic separation under IFRS9 in line 4 is similar to line 2 under IAS39, in which we choose to immediately remove the time value for the option from the hedging relationship. We therefore have to account for 40 000 of time value in the P&L.

In the last line, we separate between time and intrinsic values, but the time value of the option is aimed to be booked into OCI. In this case, a test on both the intrinsic and the time element is performed. We can therefore comprise 100 000 in the intrinsic OCI, 30 000 in the time OCI, and 10 000 as an over hedge in the P&L.

4. Cross-currency basis spread are considered a cost of hedging

The cross-currency basis spread can be defined as the liquidity premium of one currency over the other. This premium applies to exchanges of currencies in the future, e.g. a hedging instrument like an FX forward contract. If a cross currency interest rate swap is used in combination with a single currency hedged item, for which this spread is not relevant, hedge ineffectiveness could arise.

In order to cope with this mismatch, it has been decided to expand the requirements regarding the costs of hedging. Hedging costs can be seen as cost incurred to protect against unfavourable changes. Similar to the accounting for the forward element of the forward rate, an entity can exclude the cross-currency basis spread and account for it separately when designating a hedging instrument. In case a hypothetical derivative is used, the same principle applies. IFRS 9 states that the hypothetical derivative cannot include features that do not exist in the hedged item. Consequently, cross-currency basis spread cannot be part of the hypothetical derivative in the previously mentioned case. This means that hedge ineffectiveness will exist.

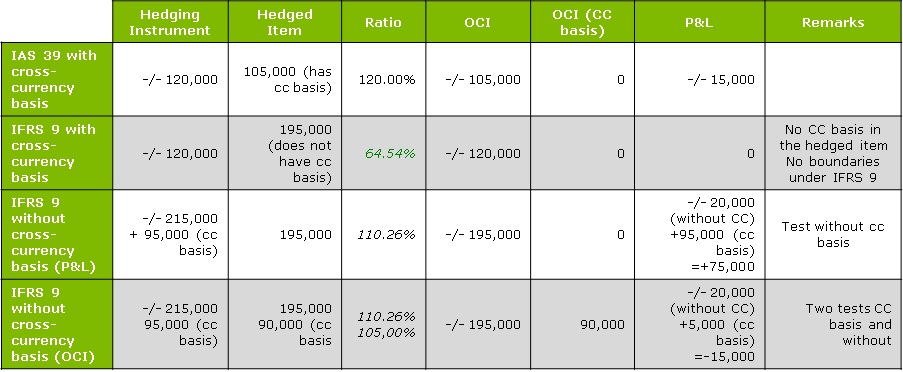

Please refer to the example below:

In example 4, we consider an entity X hedging a USD loan with a CCIRS.

MtM change of CCIRS = 215,000 – 95,000 (cross-currency basis) = 120,000.

MtM change hedged = 195,000 – 90,000 (cross-currency basis) = 105,000.

Under IAS39, there is only one way to account for CCIRS. The full amount of 120 000 (including the – 95 000 cross-currency basis) is considered as the hedging instrument, meaning that 105 000 can be listed as OCI and 15 000 of over hedge have to go to the P&L.

Under IFRS9, there is the option to exclude the cross-currency basis and account for it separately.

In line 2, we can see the conditions under IFRS9 when a cross-currency basis is included: the cross-currency basis cannot be comprised in the hedged item, so there is an under hedge of 75 000.

In line 3, we exclude the cross-currency basis from the test for the hedging instrument. By registering the MtM movement of 195 000 as OCI, we then account for the 95 000 of cross-currency basis, as well as -/- 20 000 of over hedge in the P&L. In line 4, the cross-currency basis is included in a separate hedge relationship – we therefore perform an extra test on the cross-currency basis (aligned versus actual values) . From the first test, -/- 195,000 is registered as OCI and -/- 20,000 (“over hedge” part) in P&L; from the cross-currency basis test 90,000 represents OCI and 5,000 has to be included in P&L.

The forward-looking provisions of IFRS 9

On 18 May 2017, the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) issued the new IFRS 17 standards. The development of these standards has been a long and thorough process with the aim of providing a single global comprehensive accounting standard for insurance contracts.

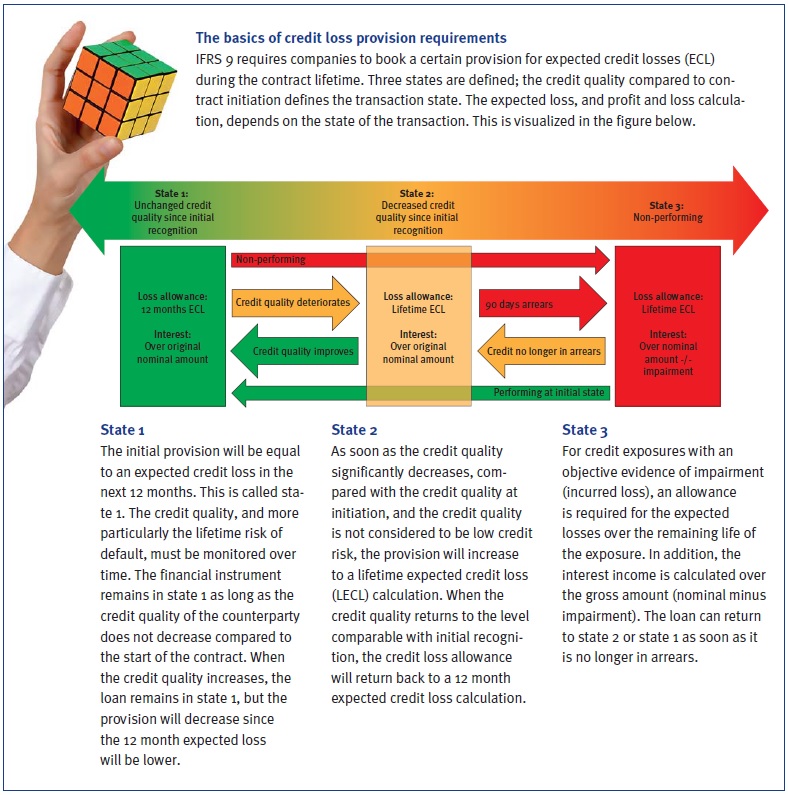

Most banks are struggling to work out how to implement the new impairment rules. Uncertainty over how to deal with current expected credit loss taking into account future macroeconomic scenarios as required by IFRS 9, means credit risk modeling experts, quants and finance experts are in uncharted waters. Different firms have different options on the matter. The primary objective of accounting standards is to provide financial information that stakeholders find useful when making decisions. The new accounting rules regarding provisions will make reserves more timely and sufficient. However, with the new standard, banks are squeezed between P&L volatility, model risk, macroeconomic forecasting and compliance with accounting standards.

Impact

IFRS 9 will, amongst others, rock the balance sheet, affect business models, risk awareness, processes, analytics, data and systems across several dimensions.

We will name a few related to the financials:

- Transition from IAS 39 to IFRS 9 will lead to a change in the level of provision for credit losses. The transition of the current provisions, which are based only on actual losses and incurred but not reported (IBNR) losses, to an expected loss is likely to have significant impact on shareholder equity, net income and capital ratios.

- P&L volatility is expected to increase after transition, since deterioration in credit quality or changes in expected credit loss will have a direct impact on P&L. The P&L volatility will, however, significantly differ per type of credit portfolio, also depending on counterparty ratings and remaining maturity. Portfolios with loans rated below investment grade will move faster from ‘state 1’ to ‘state 2’ (see box), since a move within investment grade ratings is not seen as a credit quality deterioration. Portfolios with long maturities will face large P&L volatility when moving from state 1 to state 2.

- Capital levels and deal pricing will be affected by the expected provisions.

Total P&L over time will not change, since the expected credit loss provision is booked against the actual credit losses during lifetime. If there is no actual credit loss, all provisions will fall free as profit towards maturity.

Forward-looking

IFRS 9 requires financial institutions to adjust the current backward-looking incurred loss based credit provision into a forward-looking expected credit loss. This sounds logical for an accounting provision and it assumes that existing relevant models within risk management may be applied. However, there are some difficulties to overcome.

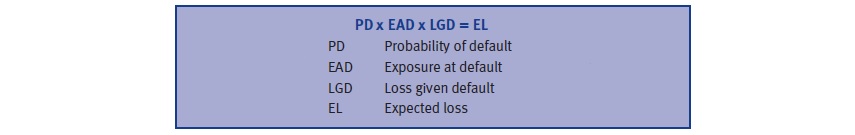

Incorporating forward-looking information means moving away from the through-the-cycle approach towards an estimation of the ‘business cycle’ of potential credit losses. A forward-looking expected credit loss calculation should be based on an accurate estimation of current and future probability of default (PD), exposure at default (EAD), loss given default (LGD), and discount factors. Discount factors according to IFRS 9 are based on the effective interest rate; this subject will not be further addressed here. The EAD can mainly be derived from current exposure, contractual cash flows and an estimate of unscheduled repayments and an expectation of the use of undrawn credit limits. Both unscheduled repayments and undrawn amounts are known to be business cycle dependent. Forecasting these items can be derived from historical observations.

Of course, the best calibration is on defaulted data since we determine exposure at default. If insufficient data is available, cycle dependent unscheduled repayments and drawing of credit limits can be derived from the entire credit portfolio, preferably corrected with some expert judgement to reflect the situation at default.

Banks have internal rating models in place to assign a PD to a counterparty and for trenching the portfolio in different levels with a specific PD. From a capital point of view, these ratings are mostly calibrated to a through-the-cycle level of observed defaults. Now using all the bank’s forward-looking information may improve estimates if business cycle(s) can be identified, potential scenarios of the development of the cycle in the future can be forecasted, including how the cycle affects a bank’s PD term structure. This would be a macroeconomic and econometric heaven if there were sufficient data available to derive accurate and statistically significant models. Otherwise, banks need to rely more on expert judgement and external macroeconomic reports.

Next to the PD term structures, LGD term structures are required to calculate a life time expected loss. Deriving an accurate LGD term structure from realized defaults requires a large default database. Deriving a business-cycle dependent LGD term structure requires an even bigger database of accurately and timely documented losses. The level of business cycle dependency of LGD significantly differs per type of counterparty, industry, and collateral. Subordination is not much cycle dependent, while loans covered with collateral, such as mortgage loans, may result in large movements in LGDs over time. Hence, this requires different LGD term structures for different LGD types and levels.

Economic scenarios

Incorporating forward-looking information means modeling business cycle dependency in your PD and LGD. For significant drivers, future scenarios are required to calculate expected credit loss. At most banks, these forward-looking scenarios are commonly the domain of economic research departments. Macroeconomic forecasting concentrates mainly on country-specific variables. Growth of domestic product, unemployment rates, inflation indices and interest rates are typical projected variables.

Usually, only large international banks with an economic research department are able to project consistent economic outlooks and scenarios. Next to macro scenarios, industry specific forecasts are important. Industry risk models enable a bank to make forecasts for a certain industry segment, e.g. chemicals, automotive or oil & gas. Industry models are often based on variables such as market conditions, barriers to entry and default data. At some banks, industries are analyzed and scored by economic researchers. At others, usually smaller banks, industries are ranked by sector business specialists.

Industry scorings often form input for rating models and are important factors for portfolio management purposes. Therefore, caution is required in correlation between drivers of ratings and drivers of the PD term structure.

Credit portfolios

For homogenous retail exposures, forward-looking elements can be considered on a portfolio level by modeling the dependencies of PD and LGD percentages for realized defaults and losses; in essence this is a bottom-up approach. For mortgage portfolios, cycle dependency relates, for example, to unemployment and house price indices, among other factors. However, statistically significant parameters and models for default relations are difficult to obtain since there is a common time gap in observing and administrating both defaults and business cycle.

Model significance can be improved by adding additional variables with increasing risk of overfitting. Even if there is statistical proof for macroeconomic dependencies in PD and LGD rates, it is advised to be cautious, since it also requires designing credible macroeconomic scenarios. As business cycles are difficult to predict, this could lead to extra P&L volatility and an increase in the complexity and ‘explainability’ of figures. Therefore, regular back-testing and continuous monitoring are important for an accurate and robust provision mechanism, especially in the first years after the model is introduced.

For non-retail exposures, country and industry risk are, if embedded in the credit rating models, already part of the annual individual credit review and rating assignment processes. In the monthly financial reporting, additional country and industry risk factors can be taken into account on a portfolio basis, making provisions more forward looking; in essence a top-down approach. If necessary, risk management can make adjustments on an individual basis for wholesale counterparties, and facilities. A forward-looking overlay should improve the accuracy of provisions and a timely and adequate recognition of credit risk, instead of “too little, too late” as under the existing rules.

Governance

Because of the forward-looking character of IFRS 9, and the increasing role of risk models, a transparent and robust governance framework will become more important. Coordination and communication are required across risk, finance, business units, audit and IT.

Risk management typically delivers the expected credit loss parameters and calculations to finance on a monthly basis. Proposals for retail and nonretail adjustments briefly described above, must be discussed and agreed upon, after which the final proposal is submitted to the approval authority.

The governance framework should be documented and reviewed on an annual basis, and highlight key functions, stakeholders, definitions, data management, model (re)development, model implementation, portfolio monitoring and validation. In addition, all parties involved should speak the same credit risk language, have access to detailed data underlying the calculation of the provision and a good under- standing of the model and implications of decisions and parametrization. Only then can the finance department obtain an accurate understanding of the level and change of the provision and clearly inform the board and other stakeholders.

Zanders recommends preparing early for IFRS 9 and having a deep and thorough understanding of the impact, as well as the robust tooling and processes in place. Don’t just wait and ‘watch the hare running’, but start early, and at least run a shadow period during daylight to allow sufficient time.

Hassle-free CECL and IFRS9 compliance? Try our new Condor ECL tool!

7 Steps to Treasury Transformation

On 18 May 2017, the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) issued the new IFRS 17 standards. The development of these standards has been a long and thorough process with the aim of providing a single global comprehensive accounting standard for insurance contracts.

Treasury transformation refers to the definition and implementation of the future state of a treasury department. This includes treasury organization & strategy, the banking landscape, system infrastructure and treasury workflows & processes.

Introduction

Zanders has witnessed first-hand a treasury transformation trend sweeping global corporate treasuries in recent years and has seen an elite group of multinationals pursue increased efficiency, enhanced visibility and reduced cost on a grand scale in their respective finance and treasury organizations.

Triggers for treasury transformations

Why does a treasury need to transform? There comes a point in an organization’s life when it is necessary to take stock of where it is coming from, how it has grown and especially where it wants to be in the future.

Corporates grow in various ways: through the launch of new products, by entering new markets, through acquisitions or by developing strong pipelines. However, to sustain further growth they need to reinforce their foundations and transform themselves into stronger, leaner, better organizations.

What triggers a treasury organization to transform? Before defining the treasury transformation process, it is interesting to look at the drivers behind a treasury transformation. Zanders has identified five main triggers:

1. Organic growth of the organization Growth can lead to new requirements.

As a result of successive growth the as-is treasury infrastructure might simply not suffice anymore, requiring changes in policies, systems and controls.

2. Desire to be innovative and best-in-class

A common driver behind treasury transformation projects is the basic human desire to be best-in-class and continuously improve treasury processes. This is especially the case with the development of new technology and/or treasury concepts.

3. Event-driven

Examples of corporate events triggering the need for a redesign of the treasury organization include mergers, acquisitions, spin-off s and restructurings. For example, in the case of a divestiture, a new treasury organization may need to be established. After a merger, two completely different treasury units, each with their own systems, processes and people, will need to find a new shape as a combined entity.

4. External factors

The changing regulatory environment and increased volatility in financial markets have been major drivers behind treasury transformation in recent years. Corporate treasurers need to have a tighter grasp on enterprise risks and quicker access to information.

5. The changing role of corporate treasury

Finally the changing role of corporate treasury itself is a driver of transformation projects. The scope of the treasury organization is expanding into the fi nancial supply chain and as a result the relationship between the CFO and the corporate treasurer is growing stronger. This raises new expectations and demands of treasury technology and organization.

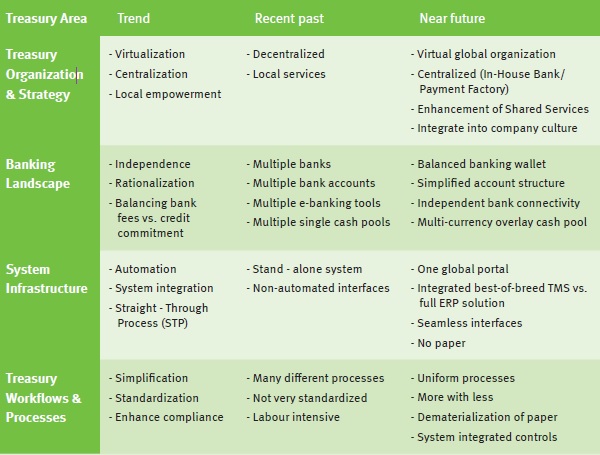

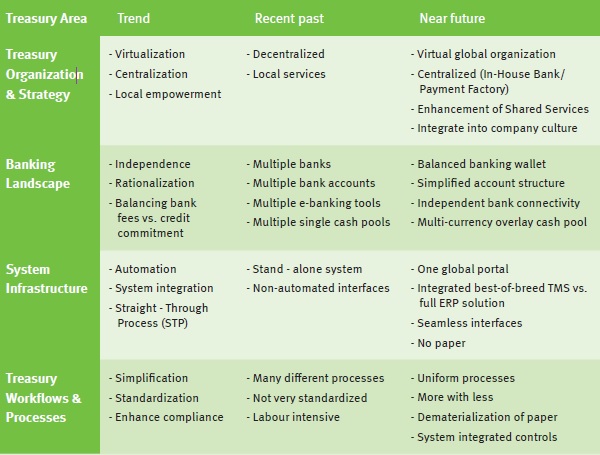

Treasury transformation – strategic opportunities for simplification

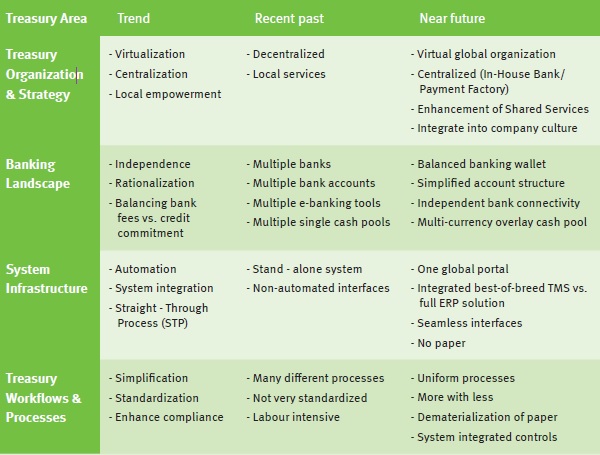

A typical treasury transformation program focuses on treasury organization, the banking landscape, system infrastructure and treasury workflows & processes. The table below highlights typical trends seen by Zanders as our clients strive for simplified and effective treasury organizations. From these trends we can see many state of the art treasuries strive to:

- be centralized

- outsource routine tasks and activities to a financial shared service centre (FSSC)

- have a clear bank relationship management strategy and have a balanced banking wallet

- maintain simple and transparent bank account structures with automatic cash concentration mechanisms

- be bank agnostic as regards bank connectivity and formats

- operate a fully integrated system landscape

Figure 1: Strategic opportunities for simplification

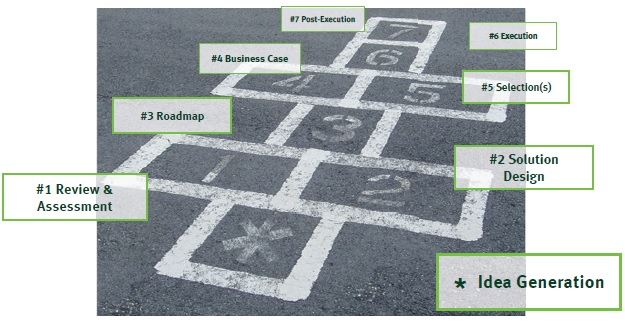

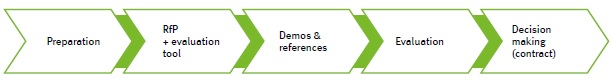

The seven steps

Zanders has developed a structured seven-step approach towards treasury transformation programs. These seven steps are shown in Figure 2 below

Figure 2: Zanders seven steps to treasury transformation projects

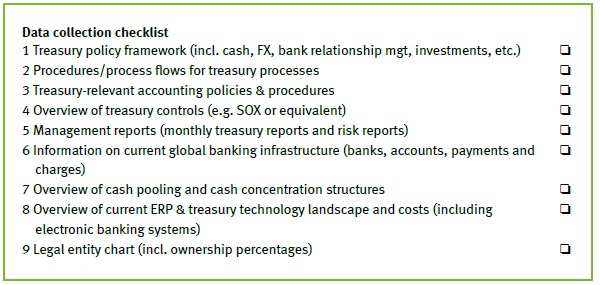

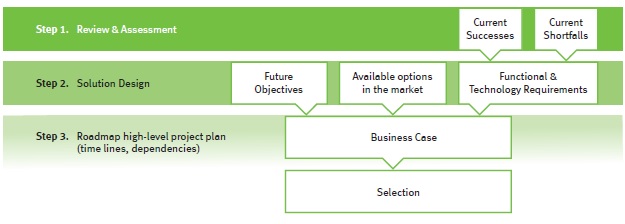

Step 1: Review & Assessment

Review & assessment, as in any business transformation exercise, provides an in-depth understanding of a treasury’s current state. It is important for the company to understand their existing processes, identify disconnects and potential process improvements.

The review & assessment phase focusses on the key treasury activities of treasury management, risk management and corporate finance. The first objective is to gain an in-depth understanding of the following areas:

- organizational structure

- governance and strategy policies

- banking infrastructure and cash management

- financial risk management

- treasury systems infrastructure

- treasury workflows and processes

Figure 3: Example of data collection checklist for review & assessment

Based on the review and assessment, existing short-falls can be identified as well as where the treasury organization wants to go in the future, both operationally and strategically.

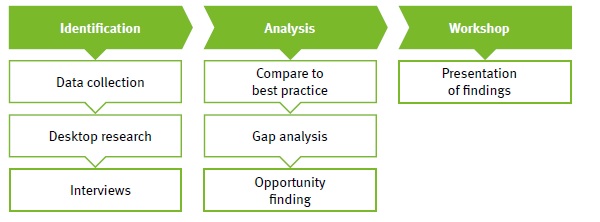

Figure 4 shows Zanders’ approach towards the review and assessment step.

Figure 4: Review & assessment break-down

Typical findings

Based on Zanders’ experience, common findings of a review and assessment are listed below:

Treasury organization & strategy:

- Disjointed sets of policies and procedures

- Organizational structure not sufficiently aligned with required segregation of duties

- Activities being done locally which could be centralized (e.g. into a FSSC), thereby realizing economies of scale

- Treasury resources spending the majority of their time on operational tasks that don’t add value and that could be automated. This prevents treasury from being able to focus sufficiently on strategic tasks, projects and fulfilling its internal consulting role towards the business.

Banking landscape:

- Mismatch between wallet share of core banking partners and credit commitment provided

- No overview of all bank accounts of the company nor of the balances on these bank accounts

- While cash management and control of bank accounts is often highly centralized, local balances can be significant due to missing cash concentration structures

- Lack of standardization of payment types and payment processes and different payment fi le formats per bank

System infrastructure:

- Considerable amount of time spent on manual bank statement reconciliation and manual entry of payments

- The current treasury systems landscape is characterized by extensive use of MS Excel, manual interventions, low level of STP and many different electronic banking systems

- Difficulty in reporting on treasury data due to a scattered system landscape

- Manual up and downloads instead of automated interfaces

- Corporate-to-bank communication (payments and bank statements processes) shows significant weaknesses and risks with regard to security and efficiency

Treasury workflows & processes:

- Monitoring and controls framework (especially of funds/payments) are relatively light

- Paper-based account opening processes

- Lack of standardization and simplification in processes

The outcome of the review & assessment step will be the input for step two: Solution Design.

Step 2: Solution Design

The key objective of this step is to establish the high-level design of the future state of treasury organization. During the solution design phase, Zanders will clearly outline the strategic and operational options available, and will make recommendations on how to achieve optimal efficiency, effectiveness and control, in the areas of treasury organization & strategy, banking landscape, system infrastructure and treasury workflows & processes.

Using the review & assessment report and findings as a starting point, Zanders highlights why certain findings exist and outlines how improvements can be implemented, based on best market practices. The forum for these discussions is a set of workshops. The first workshop focuses on “brainstorming” the various options, while the second workshop is aimed at decision-making on choosing and defining the most suitable and appropriate alternatives and choices.

The outcome of these workshops is the solution design document, a blueprint document which will be the basis for any functional and/or technical requirements document required at a later stage of the project when implementing, for example, a new banking landscape or treasury management system.

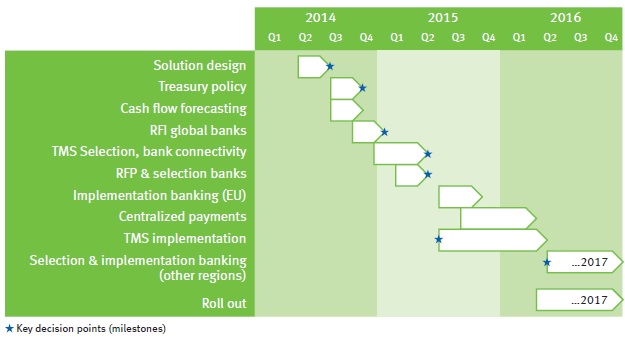

Step 3: Roadmap

The solution design will include several sub-projects, each with a different priority, some more material than others and all with their own risk profile. It is important therefore for the overall success of the transformation that all sub-projects are logically sequenced, incorporating all inter-relationships, and are managed as one coherent program.

The treasury roadmap organizes the solution design into these sub-projects and prioritizes each area appropriately. The roadmap portrays the timeframe, which is typically two to five years, to fully complete the transformation, estimating individually the duration to fully complete each component of the treasury transformation program.

“A Program is a group of related projects managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits and control not available from managing them individually”.

Zanders

Figure 5: Sample treasury roadmap

Step 4: Business Case

The next step in the treasury transformation program is to establish a business case.

Depending on the individual organization, some transformation programs will require only a very high-level business case, while others require multiple business cases; a high level business case for the entire program and subsequent more detailed business cases for each of the sub-projects.

Figure 6: Building a business case

The business case for a treasury transformation program will include the following three parts:

- The strategic context identifies the business needs, scope and desired outcomes, resulting from the previous steps

- The analysis and recommendation section forms the significant part of the business case and concerns itself with understanding all of the options available, aligning them with the business requirements, weighing the costs against the benefits and providing a complete risk assessment of the project

- The management and controlling section includes the planning and project governance, interdependencies and overall project management elements

Notwithstanding the financial benefits, there are many common qualitative benefits in transforming the treasury. These intangibles are often more important to the CFO and group treasurer than the financial benefits. Tight control and full compliance are significant features of world-class treasuries and, to this end, they are typically top of the list of reasons for embarking on a treasury transformation program. As companies grow in size and complexity, efficiency is difficult to maintain. After a period of time there may need to be a total overhaul to streamline processes and decrease the level of manual effort throughout the treasury organization. One of the main costs in such multi-year, multi-discipline transformation programs is the change management required over extended periods.

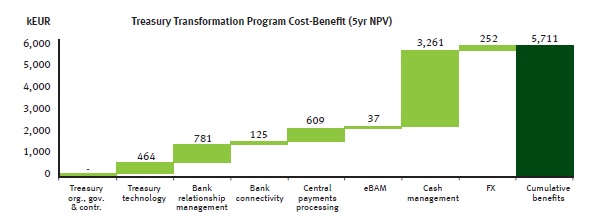

Figure 7: Sample cost-benefit

Figure 7 shows an example of how several sub-projects might contribute to the overall net present value of a treasury transformation program, providing senior management with a tool to assess the priority and resource allocation requirements of each sub-project.

Step 5: Selection(s)

Based on Zanders’ experience gained during previous treasury transformation programs, key evaluation & selection decisions are commonly required for choosing:

- bank partners

- bank connectivity channels

- treasury systems

- organizational structure

Zanders has assisted treasury departments with selection processes for all these components and has developed standardized selection processes and tools.

Selection process for bank partners

Common objectives for including the selection of banking partners in a treasury transformation program include the following:

- to align banks that provide cash and risk management solutions with credit providing banks

- to reduce the number of banks and bank accounts

- to create new banking architecture and cash pooling structures

- to reduce direct and indirect bank charges

- to streamline cash management systems and connectivity

- to meet the service requirements of the business; and

- to provide a robust, scalable electronic platform for future growth/expansion.

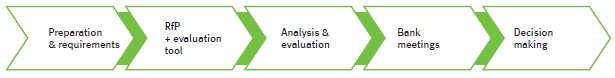

Zanders’ approach to bank partner selection is shown in Figure 8 below.

Figure 8: Bank partner selection process

Selection process for bank connectivity providers or treasury systems (treasury management systems, in-house banks, payment factories)

The selection of new treasury technology or a bank connectivity provider will follow the selection process depicted in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Treasury technology selection process

Organizational structure

If change in the organizational structure is part of the solution design, the need for an evaluation and selection of the optimal organizational structure becomes relevant. An example of this would be selecting a location for a FSSC or selecting an outsourcing partner. Based on the high-level direction defined in the solution design and based on Zanders’ extensive experience, we can advise on the best organization structure to be selected, on a functional, strategic and geographical level.

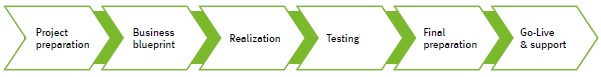

Step 6: Execution

The sixth step of treasury transformation is execution. In this step, the future-state treasury design will be realized. The execution typically consists of various sub-projects either being run in parallel or sequentially.

Zanders’ implementation approach follows the following steps during execution of the various treasury transformation sub-projects. Since treasury transformation entails various types of projects, in the areas of treasury organization, system infrastructure, treasury processes and banking landscape, not all of these steps apply to all projects to the same extent.

For several aspects of a treasury transformation program, such as the implementation of a payment factory, a common and tested approach is to go live with a number of pilot countries or companies first before rolling out the solution across the globe.

Figure 10: Zanders’ execution approach

Step 7: Post-Execution

The post-execution step of a treasury transformation is an important part of the program and includes the following activities:

6-12 months after the execution step:

– project review and lessons learned

– post implementation review focussing on actual benefits realized compared to the initial business case

On an ongoing basis:

– periodic benchmark and continuous improvement review

– ongoing systems maintenance and support

– periodic upgrade of systems

– periodic training of treasury resources

– periodic bank relationship reviews

Zanders offers a wide range of services covering the post-execution step.

Importance of a structured approach

There are many internal and external factors that require treasury organizations to increase efficiency, effectiveness and control. In order to achieve these goals for each of the treasury activities of treasury management, risk management and corporate finance, it is important to take a holistic approach, covering the organizational structure and strategy, the banking landscape, the systems infrastructure and the treasury workflows and processes. Zanders’ seven steps to treasury transformation provides such an approach, by working from a detailed as-is analysis to the implementation of the new treasury organization.

Why Zanders?

Zanders is a completely independent treasury consultancy f rm founded in 1994 by Mr. Chris J. Zanders. Our objective is to create added value for our clients by using our expertise in the areas of treasury management, risk management and corporate finance. Zanders employs over 130 specialist treasury consultants who are the key drivers of our success. At Zanders, our advisory team consists of professionals with different areas of expertise and professional experience in various treasury and finance roles.

Due to our successful growth, Zanders is a leading consulting firm and market leader in independent consulting services in the area of treasury and risk management. Our clients are multinationals, financial institutions and international organizations, all with a global footprint.

Independent advice

Zanders is an independent firm and has no shareholder or ownership relationships with any third party, for example banks, accountancy firms or system vendors. However, we do have good working relationships with the major treasury and risk management system vendors. Due to our strong knowledge of the treasury workstations we have been awarded implementation partnerships by several treasury management system vendors. Next to these partnerships, Zanders is very proud to have been the first consultancy firm to be a certified SWIFTNet management consultant globally.

Thought leader in treasury and finance

Tomorrow’s developments in the areas of treasury and risk management should also have attention focused on them today. Therefore Zanders aims to remain a leading consultant and market leader in this field. We continuously publish articles on topics related to development in treasury strategy and organization, treasury systems and processes, risk management and corporate finance. Furthermore, we organize workshops and seminars for our clients and our consultants speak regularly at treasury conferences organized by the Association of Financial Professionals (AFP), EuroFinance Conferences, International Payments Summit, Economist Intelligence Unit, Association of Corporate Treasurers (UK) and other national treasury associations.

From ideas to implementation

Zanders is supporting its clients in developing ‘best in class’ ideas and solutions on treasury and risk management, but is also committed to implement these solutions. Zanders always strives to deliver, within budget and on time. Our reputation is based on our commitment to the quality of work and client satisfaction. Our goal is to ensure that clients get the optimum benefit of our collective experience.

Replicating investment portfolios

Many banks use a framework of replicating investment portfolios to measure and manage the interest rate risk of variable savings deposits. There are two commonly used methodologies, known as the marginal investment strategy and the portfolio investment strategy. While these have the same objective, the effects for margin and interest maturity may vary. We review these strategies on the basis of a quantitative and a qualitative analysis.

A replicating investment portfolio is a collection of fixed-income investments based on an investment strategy that aims to reflect the typical interest rate maturity of the savings deposits (also referred to as ‘non-maturing deposits’). The investment strategy is formulated so that the margin between the portfolio return and the savings interest rate is as stable as possible, given various scenarios.

A replicating framework enables a bank to base its interest rate risk measurement and management on investments with a fixed maturity and price – while the deposits have no contractual maturity or price. In addition, a bank can use the framework to transfer the interest rate risk from the business lines to the central treasury, by turning the investments into contractual obligations. There are two commonly used methodologies for constructing the replicating portfolios: the marginal investment strategy and the portfolio investment strategy. These strategies have the same objective, but have different effects on margin and interest-rate term, given certain scenarios.

Strategies defined

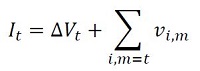

An investment strategy determines the monthly allocation of the investable volume across various maturities. The investable volume in month t ( It ) consists of two parts:

The first part is equal to the decrease or increase in the volume of savings deposits compared to the previous month. The second part is equal to the total principal of all investments in the investment portfolio maturing in the current month (end date m = t ), Σi,m=t vi,m.

By investing or re-investing the volume of these two parts, the total principal of the investment portfolio will equal the savings volume outstanding at that moment. When an investment is generated, it receives the market interest rate relating to the maturity at that time. The portfolio investment return is determined as the principal weighted average interest rate.

The difference between a marginal investment strategy and a portfolio investment strategy is that in a marginal investment strategy, the volume is invested with a fixed allocation across fixed maturities. In a portfolio strategy, these parameters are flexible, however investments are generated in such a way that the resulting portfolio each month has the same (target) proportional maturity profile. The maturity profile provides the total monthly principal of the currently outstanding investments that will mature in the future.

In the savings modelling framework, the interest rate risk profile of the savings portfolio is estimated and defined as a (proportional) maturity profile. For the portfolio investment strategy, the target maturity profile is set equal to this estimated profile. For the marginal investment strategy, the ‘investment rule’ is derived from the estimated profile using a formula. Under long lasting constant or stable volume of savings deposits, the investment portfolio given the investment rule converges to the estimated profile.

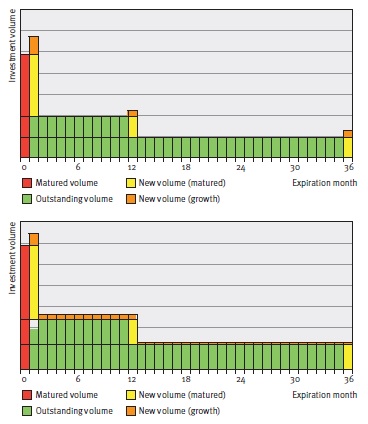

Strategies illustrated

In Figure 1, the difference between the two strategies is graphically illustrated in an example. The example provides the development of replicating portfolios of the two strategies in two consecutive months upon increasing savings volume. The replicating portfolios initially consist of the same investments with original maturities of one month, 12 months and 36 months. To this end, the same investments and corresponding principals mature. The total maturing principal will be reinvested and the increase in savings volume will be invested.

Figure 1: Maturity profiles for the marginal (figure on top) and portfolie (figure below) investment strategies given increasing volume.

Note that if the savings volume would have remained constant, both strategies would have generated the same investments. However, with changing savings volume, the strategies will generate different investments and a different number of investments (3 under the marginal strategy, and 36 under the portfolio strategy).

The interest rate typical maturities and investment returns will therefore differ, even if market interest rates do not change. For the quantitative properties of the strategies, the decision will therefore focus mainly on margin stability and the interest rate typical maturity given changes in volume (and potential simultaneous movements in market interest rates).

Scenario analysis

The quantitative properties of the investment strategies are explained by means of a scenario analysis. The analysis compares the development of the duration, margin and margin stability of both strategies under various savings volume and market interest rate scenarios.

Client interest rate

As part of the simulation of a margin, a client interest rate is modeled. The model consists of a set of sensitivities to market interest rates (M1,t) and moving averages of market interest rates (MA12,t). The sensitivities to the variables show the degree to which the bank has to reflect market movements in its client interest rate, given the profile of its savings clients.

The model chosen for the interest rate for the point in time t (CRt) is as follows:

Up to a certain degree, the model is representative of the savings interest rates offered by (retail) banks.

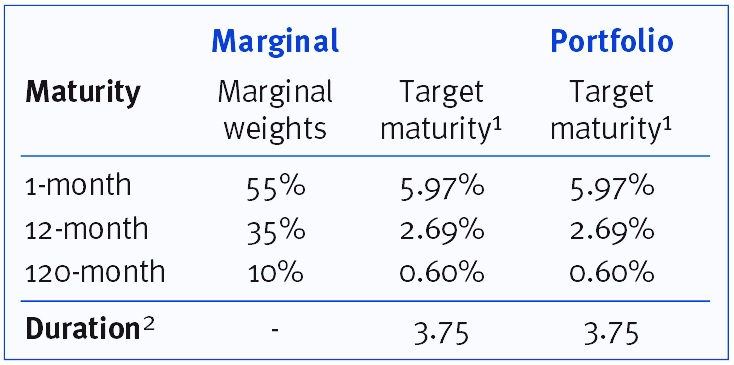

Investment strategies

The investment rules are formulated so that the target maturity profiles of the two strategies are identical. This maturity profile is then determined so that the same sensitivities to the variables apply as for the client rate model. An overview of the investment strategies is given in Table 1.

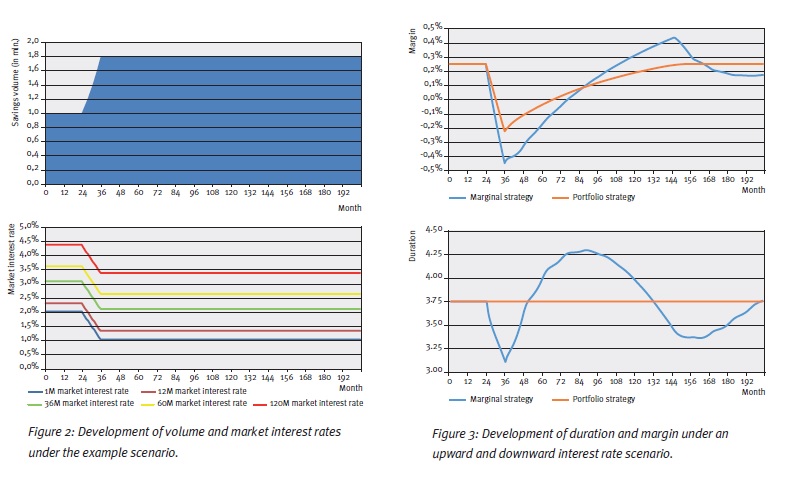

The replication process is simulated for 200 successive months in each scenario. The starting point for the investment portfolio under both strategies is the target maturity profile, whereby all investments are priced using a constant historical (normal) yield curve. In each scenario, upward and downward shocks lasting 12 months are applied to the savings volume and the yield curve after 24 months.

Example scenario

The results of an example scenario are presented in order to show the dynamics of both investment strategies. This example scenario is shown in Figure 2. The results in terms of duration and margin are shown in Figure 3.

As one would expect, the duration for the portfolio investment strategy remains the same over the entire simulation. For the marginal investment strategy, we see a sharp decline in the duration during the ‘shock period’ for volume, after which a double wave motion develops on the duration. In short, this is caused by the initial (marginal) allocation during the ‘stress’ and subsequent cycles of reinvesting it.

With an upward volume shock, the margin for the portfolio strategy declines because the increase in savings volume is invested at downward shocked market interest rates. After the shock period, the declining investment return and client rate converge. For the marginal strategy this effect also applies and in addition the duration effects feed into the margin development.

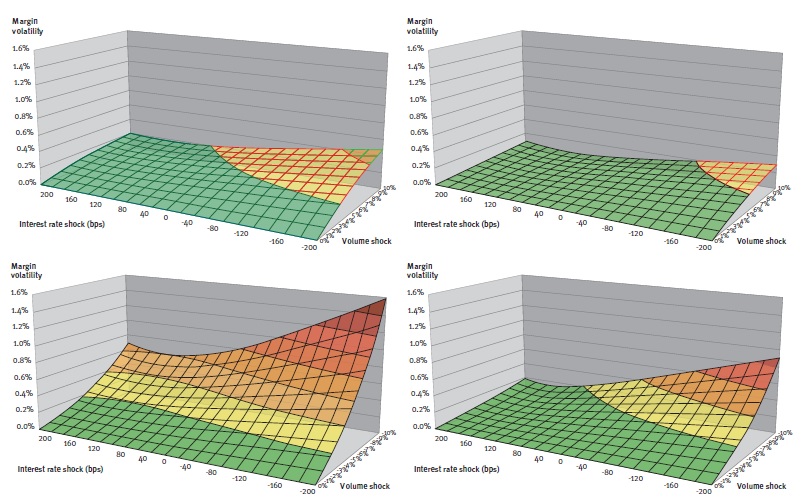

Scenario spectrum

In the scenario analysis the standard deviation of the margin series, also known as the margin volatility, serves as a proxy for margin stability. The results in terms of margin stability for the full range of market interest rate and volume scenarios are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Margin volatility of marginal (left-hand figure) and portfolio strategy (right-hand figure) for upward (above) and downward (below) volume shocks.

From the figures, it can be seen that the margin of the marginal investment strategy has greater sensitivity to volume and interest rate shocks. Under these scenarios the margin volatility is on average 2.3 times higher, with the factor ranging between 1.5 and 4.5. In general, for both strategies, the margin volatility is greatest under negative interest-rate shocks combined with upward or downward volume shocks.

Replication in practice

The scenario analysis shows that the portfolio strategy has a number of advantages over the marginal strategy. First of all, the maturity profile remains constant at all times and equal to the modeled maturity of the savings deposits. Under the marginal strategy, the interest rate typical maturity can vary from it over long periods, even when there are no changes in market interest environment or behavior in the savings portfolio.

Secondly, the development of the margin is more stable under volume and interest rate shocks. The margin volatility under the marginal investment strategy is actually at least one and a half times higher under the chosen scenarios.

An intuitive process

These benefits might, however, come at the expense of a number of qualitative aspects that may form an important consideration when it comes to implementation. Firstly, the advantage of a constant interest-rate profile for the portfolio strategy, comes at the expense of intuitive combinations of investments. This may be important if these investments form contractual obligations for the transfer of the interest rate risk.

The strategy, namely, requires generating a large number of investments that can even have negative principals in case of a (small) decline of savings volume. Secondly, the shocks in the duration in a marginal strategy might actually be desirable and in line with savings portfolio developments. For example, if due to market or idiosyncratic circumstances there is high inflow of deposit volume, this additional volume may be relatively more interest rate sensitive justifying a shorter duration.

Nevertheless, the example scenario shows that after such a temporary decline a temporary increase will follow for which this justification no longer applies.

The choice

A combination of the two strategies may also be chosen as a compromise solution. This involves the use of a marginal strategy whereby interventions trigger a portfolio strategy at certain times. An intervention policy could be established by means of limits or triggers in the risk governance. Limits can be set for (unjustifiable) deviations from the target duration, whereas interventions can be triggered by material developments in the market or the savings portfolio.

In its choice for the strategy, the bank is well-advised to identify the quantitative and qualitative effects of the strategies. Ultimately, the choice has to be in line with the character of the bank, its savings portfolio and the resulting objective of the process.

- The profile shown is a summary of the whole maturity profile. In the whole profile, 5.97% of the replicating volume matures in the first month, 2.69% per month in the second to the 12th month, etc.

- Note that this is a proxy for the duration based on the weighted average maturity of the target maturity profile.

An extended version of this article is published in our Savings Special. Would you like to read it? Please send an e-mail to marketing@zanders.eu.

More articles about ‘The modeling of savings’:

The Matching Adjustment versus the Volatility Adjustment

On 18 May 2017, the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) issued the new IFRS 17 standards. The development of these standards has been a long and thorough process with the aim of providing a single global comprehensive accounting standard for insurance contracts.

On April 30th 2014, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) published the technical specifications for the preparatory phase towards Solvency II. The technical specifi cations on the long-term guarantee package offer the insurers basically two options to mitigate ‘artificial’ fluctuations in their own funds, the Volatility Adjustment and the Matching Adjustment. What is their impact and what are the main differences between these two measures?

Solvency II aims to unify the EU insurance market and will come into effect on January 1st 2016. The technical specifications published by EIOPA will be used for interim reporting during 2015.

Although the specifications are not yet finalized, it is unlikely that they will change extensively. The technical specifications consist of two parts; part one focuses on the valuation and calculation of the capital requirements and part two focuses on the long-term guarantee (LTG) package. The LTG package was agreed upon in November 2013 and has been one of the key areas of debate in the Solvency II legislation.

Artificial volatility

The LTG package consists of regulatory measures to ensure that short-term market movements are appropriately treated with regards to the long-term nature of the insurance business. It aims to prevent ‘artificial’ volatility in the ‘own funds’ of insurers, while still reflecting the market consistent approach of Solvency II. When insurance companies invest long-term in fixed income markets, they are exposed to credit spread fluctuations not related to an increased probability of default of the counterparty.

These fluctuations impact the market value of the assets and own funds, but not the return of the investments itself as they are held to maturity. The LTG package consists of three options for insurers to deal with this so-called ‘artificial’ volatility: the Volatility Adjustment, the Matching Adjustment and transitional measures.

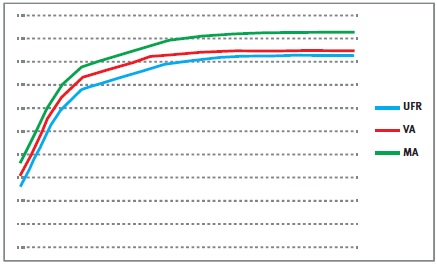

Figure 1

The transitional measures allow insurers to move smoothly from Solvency I to Solvency II and apply to the risk-free curve and technical provisions. However, the most interesting measures are the Volatility Adjustment and the Matching Adjustment. The impact of both measures is difficult to assess and it is a strategic choice which measure should be applied.

Both try to prevent fluctuations in the own funds due to artificial volatility, yet their requirements and use are rather different. To find out more about these differences, we immersed ourselves into the impact of the Volatility Adjustment and the Matching Adjustment.

The Volatility Adjustment

The Volatility Adjustment (VA) is a constant addition to the risk-free curve, which used to calculate the Ultimate Forward Rate (UFR). It is designed to protect insurers with long-term liabilities from the impact of volatility on the insurers’ solvency position. The VA is based on a risk-corrected spread on the assets in a reference portfolio. It is defined as the spread between the interest rate of the assets in the reference portfolio and the corresponding risk-free rate, minus the fundamental spread (which represents default or downgrade risk).

The VA is provided and updated by EIOPA and can differ for each major currency and country. The VA is added to the liquid part of the risk-free zero-coupon rates, i.e. until the so-called Last Liquid Point (LLP). After the LLP, the curve converges to the UFR. The resulting rates are used to produce the relevant risk-free curve.

The Matching Adjustment

The Matching Adjustment (MA) is a parallel shift applied to the entire basic risk-free term structure and serves the same purpose as the VA. The MA is calculated based on the match between the insurers’ assets and the liabilities. The MA is corrected for the fundamental spread. Note that, although the MA is usually higher than the VA, the MA can possibly become negative. The MA can only be applied to a portfolio of life insurance obligations with an assigned portfolio of assets that covers the best estimate of the liabilities.

The mismatch between the cash flows of the assets and the cash flows of the liabilities must not be a material risk in relation to the risks inherent to the insurance business. These portfolios need to be identified, organized and managed separately from other activities of the insurers. Furthermore, the assigned portfolio of assets cannot be used to cover losses arising from other activities of the insurers.

The more of these portfolios are created for an insurance company, the less diversification benefits are possible. Therefore, the MA does not necessarily lead to an overall benefit.

Differences between VA and MA

The main difference between the VA and the MA is that the VA is provided by EIOPA and based on a reference portfolio, while the MA is based on a portfolio of the insurance company.

Other differences include:

- The VA is applied until the LLP, after which the curve converges to the UFR, while the MA is a parallel shift of the whole risk-free curve;

- The MA can only be applied to specifically identified portfolios;

- The VA can be used together with the transitional measures in the preparatory phase, the MA cannot;

- The MA has to be taken into account for the calculation of the Solvency Capital Requirement (SCR) for spread risk. The VA does not respond to SCR shocks for spread risks.

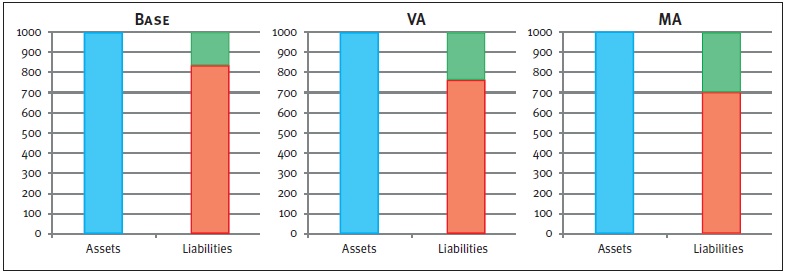

Figure 2: Graphical representations of balance sheets. The blue box represents the assets, the red box the liabilities, and the green box the available capital.

The impact of the VA and MA is twofold. Both adjustments have a direct impact on the available capital and next to this, the MA impacts the SCR. As a result, the level of free capital is affected as well. While the exact impact of the adjustments depends on firm-specific aspects (e.g. cash flows, the asset mix), an indication of the effects on available capital as well as the SCR is given in Figure 2. Please note that this is an example in which all numbers are fictitious and used merely for illustrative purposes.

Impact on available capital

Both the VA and the MA are an addition to the curve used to discount the liabilities, and will therefore lead to an increase in the available capital. The left chart in Figure 2 shows the Base scenario, without adjustment to the risk-free curve. Implementing the VA reduces the market value of the liabilities, but has no effect on the assets. As a result, the available capital increases, which can be seen in the middle chart.

A similar but larger effect can be seen in the right chart, which displays the outcome of the MA. The larger effect on the available capital after the MA compared to the VA is due to two components.

- The MA is usually higher than the VA, and

- the MA is applied to the whole curve.

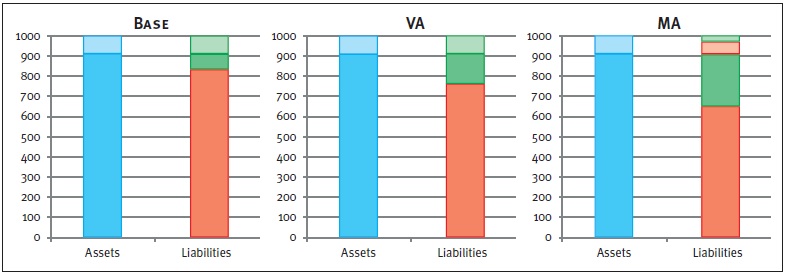

Impact on the SCR

The calculation of the total SCR, using the Standard Formula, depends on several marginal SCRs. These marginal SCRs all represent a change in an associated risk factor (e.g. spread shocks, curve shifts), and can be seen as the decrease in available capital after an adverse scenario occurs. The risk factors can have an impact on assets, liabilities and available capital, and therefore on the required capital.

Take for example the marginal SCR for spread risk. A spread shock will have a direct, and equal, negative impact on the assets for each scenario. However, since a change in the assets has an impact on the level of the MA, the liabilities are impacted too when the MA is applied. The two left charts in Figure 3 show the results of an increase in the spread, where, by applying the spread shock, the available capital decreases by the same amount (denoted by the striped boxes).

Figure 3: Graphical representations of balance sheets after a positive spread shock. The lined boxes represent a decrease of the corresponding balance sheet item. Note that, in the MA case, the liabilities decrease (striped red box) due to an increase of the MA.

Hence, the marginal SCR for the spread shock will be equal for the Base case and the VA case. The right chart displays an equal effect on the assets. However, the decrease of the assets results in an increase of the MA. Therefore, the liabilities decrease in value too. Consequently, the available capital is reduced to a lesser extent compared to the Base or VA case.

The marginal SCR example for a spread shock clearly shows the difference in impact on the marginal SCR between the MA on the one hand, and the VA and Base case on the other hand. When looking at marginal SCRs driven by other risk factors, a similar effect will occur. Note that the total SCR is based on the marginal SCRs, including diversification effects. Therefore, the impact on the total SCR differs from the sum of the impacts on the marginal SCRs.

Impact on free capital

The impact on the level of free capital also becomes clear in Figure 3. Note that the level of free capital is calculated as available capital minus required capital. It follows directly that the application of either the VA or the MA will result in a higher level of free capital compared to the Base case. Both adjustments initially result in a higher level of available capital.

In addition, the MA may lead to a decrease in the SCR which has an extra positive impact on the free capital. The level of free capital is represented by the solid green boxes in Figure 3. This figure shows that the highest level of free capital is obtained for the MA, followed by the VA and the Base case respectively.

Conclusion

Our example shows that both the VA and the MA have a positive effect on the available capital. Apart from its restrictions and difficulties of the implementation, the MA leads to the greatest benefits in terms of available and free capital.

In addition, applying the MA could lead to a reduction of the SCR. However, the specific portfolio requirements, practical difficulties, lower diversification effects and the possibility of having a negative MA, could offset these benefits.

Besides this, the MA cannot be used in combination with the transitional measures. In order to assess the impact of both measures on the regulatory solvency position for an insurance company, an in-depth investigation is required where all firm specific characteristics are taken into account.

Ultimate Forward Rate: does it create more risk?

On 18 May 2017, the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) issued the new IFRS 17 standards. The development of these standards has been a long and thorough process with the aim of providing a single global comprehensive accounting standard for insurance contracts.

The UFR is a method of adjusting the market rate at which future commitments are discounted. Interests for durations of more than 20 years are adjusted by converging the one-year forward rate towards the Ultimate Forward Rate of 4.2%.

The introduction of the UFR was an attempt to address three problems. Firstly, as interest rates currently stand, applying the UFR has the effect of increasing rates with a maturity of 20 years or more (see figure 1). This causes the present value of long-term liabilities to fall, which means funding ratios and capital ratios rise. Secondly, the interest rate market for long maturities is assumed to be insufficiently liquid to permit a reliable market valuation, which means the value of liabilities may be very volatile.

Figure 1: Spot yield curve with UFR (red) and without UFR (blue) as of September 30, 2013

The third problem addressed by the UFR is the desire to escape the vicious circle which is created when interest rate risks are hedged. Due to demand among pension funds and insurers for swaps with long maturities, these interest rates are falling, necessitating further interest rate hedging and triggering a renewed rise in demand.

Risk management

The UFR, however, is raising questions about risk management by insurers and pension funds, who are required to use the UFR when valuing their liabilities in their regulatory reports. From a risk management perspective, however, there are important arguments against hedging interest rate risks on the basis of the UFR.

The UFR is not an economic reality: there are no instruments on the market which generate the same returns as the UFR-adjusted interest rates. Consequently, there is an imbalance between the value as reported to DNB and the available instruments on the market for managing the risks. Furthermore, the UFR is only applied to the liabilities on the balance sheet, and not to the assets. This creates a discrepancy between the economic reality of the assets and the ‘paper’ UFR reality of the liabilities. If a company’s assets and liabilities have identical interest rate profiles, the company does not run an interest rate risk; nonetheless, its UFR-based funding ratio does change in line with interest rate movements on the market. There is also greater interest rate sensitivity around the 20-year interest rate point: past this point, market interest rates are partially or entirely disregarded. Lastly, there is a political risk (which cannot be hedged) that the UFR method may be revised by the regulator – a fact underlined by recent developments.

Insurers and pension funds are compelled to keep two different sets of records: a ‘UFR report’ for the regulator and an economic version on which the interest rate risk is actually managed. Both records have their own, specific risks.

Insurers: debate and uncertainty

Understandably, the UFR has created quite a furor among insurers. In June 2013, EIOPA published the results of a survey of insurers who offer long-term guarantee products. Interestingly, EIOPA acknowledges in this publication that the UFR entails significant risks. Potentially, the UFR could mislead regulators, meaning that any action is taken too late. Moreover, the design of the UFR – specifically, the speed at which the forward rate converges towards the UFR – has long been a source of uncertainty. EIOPA advises using what is known as the ‘20+40’ convergence (whereby market interest rates are used up to and including 20 years and, 40 years later, the forward rate has converged to the UFR). Both insurers and the European Parliament, however, are pressing for a switch to a ‘20+10’ convergence.

Proponents of this shorter convergence period point to the lower sensitivity to shocks in (long-term) market interest rates, which would help stabilize the valuation of liabilities. One drawback of a short convergence period is the increased volatility of own funds. This is because the assets are discounted at market interest rates and are sensitive to changes in interest rates, whereas the liabilities are not. Moreover, the potential impact of a change in the level of the UFR is greater when the convergence period is shorter.

While the debate continues among European insurers, DNB has already compelled Dutch insurers to use the UFR. In so doing, DNB is largely taking its cue from EIOPA’s latest advice. However, there is a high risk that the convergence period will change in the definitive Solvency II legislation, meaning that, eventually, insurers will have to switch to a different UFR.

Pensions: DNB is pursuing its own course

The UFR committee

In October 2013, the UFR committee advised the Dutch cabinet to abandon the current method for pension funds, which involves a fixed UFR of 4.2%. The committee advises using the UFR as an ultimate rate, based on the average forward rates of the last 120 months, with an infinite convergence period.

The UFR will then become a moving target based on current market rates. As things currently stand, this would mean a UFR of 3.9% – which is significantly different to the current UFR.

The cabinet informed the UFR committee in a response that the recommendation of applying a moving target UFR will be implemented from 2015 onwards. This will only accentuate the contrast between Europe and the Dutch pension landscape. In addition to an economic report and the current UFR report, it will compel pension funds to also prepare an adjusted UFR report for 2015.

The situation as regards pension funds illustrates the political risk. Following criticism in Dutch academic circles about the high sensitivity affecting the 20-year forward rate, DNB adapted the rules specifically for pension funds. These funds must now continue applying the forward rate past the 20-year point (with fixed weightings) and the spot rates are averaged over the last three months.

Since then, in its advisory report, the UFR committee has proposed a completely new calculation method (see insert), which may have a big impact on funding ratios. It is not inconceivable that, if the yield curve fluctuates significantly, the UFR will yet again be changed. In addition, there are also long-term risks to be taken into account. The UFR could potentially create discrepancies between the pension entitlements of current and future pensioners.

The higher funding ratio resulting from the application of the UFR reduces the likelihood of increases in contributions and cuts to pensions at the present time – which is an advantage for current pensioners. If, however, the yield turns out lower than assumed, future pensioners will have fewer funds at their disposal. Potentially, therefore, pension rights may end up being transferred from younger to older generations.

Conclusion

The EIOPA study and the UFR committee illustrate that the introduction of the UFR has made the world of insurance more complex. In risk management terms, it has created two landscapes and it is not yet clear exactly what the UFR landscape will look like. From an economic perspective, the majority of risk managers will give priority to hedging risks. To prevent interference by the regulator, however, the UFR value must always be closely monitored. Furthermore, the impending change to the UFR method for pension funds reaffirms that the political risk is a significant, unmanageable factor.

Making a SWIFT Decision: Alliance Lite or Service Bureau?

On 18 May 2017, the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) issued the new IFRS 17 standards. The development of these standards has been a long and thorough process with the aim of providing a single global comprehensive accounting standard for insurance contracts.

Corporate treasurers often look to SWIFT to standardise cross-border messaging, to facilitate payments and other financial transactions, and to avoid being bound to one bank’s proprietary system. With SWIFT’s launch of the cloud-based new Alliance Lite2 (AL2) last year and the recent introductions of new requirements and certification of SWIFT service bureau (SSB), the question is how can corporate treasurers choose the best way to connect to SWIFTNet?

With the introduction of AllianceLite (AL1) in 2008, SWIFT originally targeted smaller corporations with a lower volume of payment messages and a limited number of message types, with the option of connecting through the internet. The volume restrictions of AL1 proved to be a limiting factor and was among the reasons why many companies did not consider to offer a practical solution.