How to integrate into your governance, risk management and ORSA

Climate change risks are relatively newly identified risks that insurers are facing. These risks can negatively impact both assets and liabilities of insurers. Already in 2018, the European Commission requested the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) to investigate how climate change risk could be integrated into the Solvency II Framework.

After various previous publications1 of (draft) opinions, the investigation resulted in EIOPA’s opinion to include climate change risk scenarios in Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA)2. It basically points out that forward-looking management of climate change risks is essential, and that EIOPA expects insurers to integrate climate change risk scenarios in their ORSA. EIOPA indicates it will start monitoring the application of this opinion two years after publication, i.e. as of April 2023. However, some National Competent Authorities already require insurers to take climate change risks into account.3

So, what will be expected of insurers?

In general terms, insurers are expected to:

- Integrate climate change risks in their system of governance, risk management system and ORSA

- Assess climate change risk in ORSA in the short and long term

- Disclose climate-related information

But what does this mean in practice? We will further explained this per topic.

Integrating climate change risks

The integration requirement ensures that climate change risk becomes an integral part of the day-to-day business and the risk management framework. The EIOPA opinion does not provide much detail on what this entails. Draft amendments to the delegated regulation, published by the European Commission, provide more insight into what insurers can expect.

The draft amendments relate especially to the implementing measures of the system of governance laid out in the Solvency II Directive. This means that responsibilities regarding climate change risk need to be clearly allocated towards the key functions within the organization, and appropriately segregated to ensure an effective system of governance.

This means climate change risk should be included in the following functions/processes:

- Risk Management

For all the relevant risk management areas – covering both the asset and the liability side of the balance sheet, and including liquidity, concentration and operational risk – climate change risks need to be identified, measured, monitored, managed and reported on. - ORSA

The ORSA is a mandatory part of the required system of governance for insurers and will therefore also have to take climate risks into account. In order to properly assess the potential impact of climate change risks and the resilience of the insurers’ business model, these climate change risks need to be analyzed over a longer horizon. EIOPA has therefore advised to include climate change scenarios in the ORSA. This will be discussed in more detail in the next section of this article. - Internal Control and Internal Audit

Changes in the system of governance, risk management and ORSA to incorporate climate change risk also requires extension of the internal control system and the scope of internal audit. - Actuarial Function

The actuarial function will be responsible for the appropriateness of assumptions, methodologies and models used to assess the impact of climate change risks in underwriting. Especially in the context of ORSA and the assessment of the influence climate risk has on future reserving and capital needs. In addition, the actuarial function will be responsible for the sufficiency and quality of the data used within these calculations.

Consequently, written policies regarding risk management, internal control, internal audit, outsourcing (where relevant) and contingency plans need to be updated to include everything outlined above with regards to climate change risk.

Assess climate change risk in ORSA in the short and long term

Insurers will be required to assess climate change risk in ORSA by analyzing at least two climate scenarios. For the implementation we suggest a four-step approach, largely based on the guidance provided by EIOPA.

Step 1 – Risk identification

EIOPA expects insurers to take a broad view of climate change risks and include all risks stemming from trends or events caused by climate change. EIOPA provides a list of these risks, which distinguishes between:

- Transition risks

These are defined as follows: ‘Risks that arise from the transition to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy’. This includes the following aspects: Policy, Legal, Technology, Market sentiment and Reputational risks. - Physical risks

These are defined as: ‘risks that arise from the physical effects of climate change’ and are subdivided in acute and chronic physical risks.

Materialization of these risks for insurers will translate into impact on traditional risk categories, such as underwriting risk, market risk, credit and counterparty risk, operational risk, reputational risk and strategic risk. To help insurers get started with the implementation of climate change risks in ORSA, EIOPA has provided examples of a mapping in the annex of their opinion.

Step 2 – Materiality assessment

Insurers will be required to include all material climate change risks in ORSA. Under Solvency II, risks are considered material if ignoring the risk could lead to different decision making. This means that insurers are required to assess the materiality of each risk to determine whether these need to be included. If an insurer concludes that a certain climate change risk is immaterial, the insurer must be able to explain how that conclusion was reached.

The materiality assessment should be a combination of a qualitative and a quantitative analysis. The qualitative analysis is to provide insight in the relevance of the climate change risk drivers and the way they impact the traditional prudential risks (underwriting risk, market risk etc.). The quantitative analysis will be used to determine the extent to which assets and liabilities are exposed to transition and physical risks.

Step 3 – Defining scenarios

The inclusion of the forward-looking, risk-based approach to ORSA requires insurers to define a set of climate change risk scenarios. EIOPA expects insurers to assess material climate change risks utilizing ‘a sufficiently wide range of stress tests or scenario analysis, including the material short- and long-term risks associated with climate change’. The goal of these scenarios is to assess the resilience and robustness of the insurer’s business strategies, including the impact of risk mitigating measures.

EIOPA states that insurers may develop their own climate scenarios or build on existing ones and provides a number of sources of publicly available scenarios containing pathways for physical and transition risks. The decision for internal scenario development versus building on publicly available may depend on many factors like expected materiality or company size. For example, the underwriting risk for a life insurer is probably less exposed to transition risk than the underwriting risk for a non-life insurer, and a smaller insurer may not have sufficient expertise and resources.

The scenarios must project a multitude of external factors to properly capture the effects of climate change risks. Factors such as demographics (e.g. in case of natural disasters), economic development (e.g. as a result of technological breakthrough) and government policies to reduce carbon emissions, just to name a few. The climate change scenario set should contain at least two long-term climate scenarios:

- Global temperature increase remains below 2◦C, preferably no more than 1.5◦C, in line with Paris Agreement;

- Global temperature increase exceeds 2◦C.

In addition, a reference scenario is needed to be able to determine the impact of the stress scenarios.

The assessment is to be performed for several time horizons. Given the nature of climate change risks, horizons need to be in the order of decades. EIOPA provides examples for length of time horizons, ranging from instantaneous (‘current climate change’) to projected views of climate change for the next 80 years (‘long-term climate change’).

Step 4 – Climate change risk modeling

Modeling climate change risks in ORSA introduces two challenges:

- Assessment of transition and physical risk impacts

Materialization of transition and physical risks will have to be translated to impact on assets and liabilities. In a discussion paper, EIOPA provides examples of different methodologies for the assessment of transition impacts on assets, that have already been developed by academics, research institutes and regulators4. In general, these methodologies use carbon-sensitivities of financial instruments to assess the impact of climate change risk scenarios.

The basis for the determination of physical risks is the change in temperature over time. This change needs to be translated into impact on frequency and severity of acute natural disasters (e.g. storms, floods, fires or heatwaves) and chronic effects (e.g. rising sea levels, reduced water availability, biodiversity loss and changes in land and soil productivity). The next step is to translate these effects into impact on assets and liabilities. The translation into financial impact on companies in which insurers invest can especially be challenging. Larger companies often have a greater diversity of activities and are more spread out geographically. In addition, companies will not only be hindered by the materialization of physical risks in their own activities, but their supply chain can also be affected. However, some scoring models already exist in which companies are ranked based on their sensitivity to physical risks.5 - Long-term multi-period modeling

Incorporation of the climate change risk scenarios in ORSA aims to assess the viability of current business models and strategies and the adequacy of the insurers’ solvency. For longer horizons, insurers may use a lower precision for balance sheet projections and conduct assessment at a lower frequency than short-term risk assessments.

The lower precision allows for simplifications as long as the long-term character of the climate change scenarios is preserved. Simplifications may include projecting simple ratios instead of full balance sheets, or assessment of climate change impact on assets and technical provisions in isolation. However, projection of the full balance sheet ensures internal consistency and may provide much more information, especially when assessing the impact of potential management actions to mitigate the impact of climate change risks.

Disclose climate-related information

Insurers are expected to provide explanation on the short- and long-term climate change risk analysis in the ORSA report. This should include:

- An overview of all material risks, how materiality is assessed and an explanation for each risk that is considered immaterial.

- The methods and assumptions used by the insurer in both the materiality assessment of the climate change risks and in ORSA.

- The outcomes and conclusions of the scenario analysis, both quantitative and qualitative.

In addition, climate change risk related disclosures should be consistent with the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD).6

How can Zanders help?

As mentioned in the introduction, climate change risks are relatively new to the insurance sector. The same holds for other financial industries like the banking sector and asset management sector. As a consultancy firm for the financial industry, we support various types of financial institutions with the implementation of ESG and climate-related strategies and regulations. In doing so, we can benefit from our experience gained in the insurance, banking and asset management sectors.

We can assist with the implementation of climate change risk management, including:

- Identification of climate change risk exposures and materiality assessment

- Integration of climate change risks in your system of governance and risk management system

- Incorporate climate change risk into your ORSA, including

- Mapping climate change risks to traditional prudential risk categories

- Development of climate change risk scenarios

- Climate change risk modeling

- Support in setting up or adjusting disclosures

Sources

[1] Previous EIOPA publications related to climate change risk:

- Opinion on Sustainability within Solvency II, 30 September 2019

- draft Opinion on the supervision of the use of climate change risk scenarios in ORSA, 5 October 2020

[2] Opinion on the supervision of the use of climate change risk scenarios in ORSA, 19 April 2021

[3] See:

- DNB>Insurers>Prudential supervision> Q&A Climate-related risks and insurers (February 2021)

- PRA: Supervisory Statement 3/19 – Enhancing banks’ and insurers’ approaches to managing the financial risks from climate change (April 2019)

[4] Second Discussion Paper on Methodological principles of insurance stress testing, 24 June 2020

[5] See footnote 4

[6] Guidelines on non-financial reporting: Supplement on reporting climate-related information, 17 June 2019

LyondellBasell – Business Case

LyondellBasell, headquartered in the Netherlands, is one of the largest plastics, chemicals and refining companies in the world. With its global presence and significant operations in the United States, the company has been affected by the IBOR reform. The Treasury team was well aware of this impact and proactively approached the transition away from the IBOR rates in order to be ready ahead of time.

While it was a global and multi-functional project, one of the first goals was to ensure the TMS readiness for the calculation with alternative reference rates and the new discounting methodologies. As part of the action plan, the LyondellBasell (LYB) Treasury team (supported by procurement and IT) issued an RfP in Q4 2020 with the aim to get external support for (a) the required system changes, (b) to provide business support for initial transition plans and (c) to adhere to the best-in-class ambition of the company.

Preparing for the transition

LYB selected Zanders as implementation partner and right after the selection the project kicked off in January 2021. Urszula Chwala, was the Treasury Lead for LYB and she outlines why LYB initiated the project earlier than many other corporates: “The project team was already busy since the beginning of 2020. We analyzed the potential global impact of the IBOR reform to LYB. Amongst other impacts we were aware that LYB’s SAP Treasury Management System was highly customized, especially in the area of SAP In-house Cash. As such, we wanted to make sure that we would be ready for the transition to support our business and to enable all teams at LYB to move forward with changes on financial, commercial and legal matters.” Urszula also further comments on the RfP process: “We were looking into the third party that had both technical and business knowledge related to the IBOR reform and could bridge the gap between LYB IT and the Treasury department.”

Appreciated approach

LYB is using SAP ECC EHP8 as their treasury system and as such the standard functionality developed by SAP to support daily compound interest calculation could be implemented. On the Zanders side, SAP consultant Aleksei Abakumov, Adela Kozelova (who fulfilled the role of the business expert and project manager) and Anuja Naiknavare in the role of support consultant have been closely working with LYB’s Treasury and IT teams throughout the project.

“Zanders made this project as easy as it could be. What I really appreciated was the approach taken by Zanders team. They have taken all the suggestions from us and tested them and then came up with additional suggestions as well. The Zanders team was thinking with us, taking our best interest in mind. They supported us in every detail and removed concerns and roadblocks. Zanders also acted as business alliance in the project to ensure that all business requirements are now fully translated into the technical solution,” Urszula says.

A new functionality

In order to achieve system readiness, the project included configuration and diligent testing of a new data feed source which was required as a base to enable the daily average compound, the simple compound interest calculation and the new evaluation type with enhanced discounting curves. Considering the uncertainty, the availability of the new alternative reference rates, market conventions and the exact timing, the project’s aim was to make sure that the system would be able to support different variations of interest calculation. The project went successfully live in May 2021.

Urszula outlines different challenges encountered in the project: “Technically the biggest challenge was finding the right market data feed for the new rates. The challenge was finding the source and, making it available in SAP and test all scenarios. For the actual transactions, the system is a lot more flexible with respect to entering transactions, which makes a deal capture more complex. But Aleksei has supported the team a lot in navigating through the new functionality and we are confident to enter new deals with overnight risk-free rates. On the business side, the market clarity, especially with regards to market conventions, is still challenging the business cutover.”

Transactions

On the transition side, Treasury was cautiously managing the exposure to the IBOR reform by refraining from entering variable interest rate referencing transactions over the last two years. As a result, there is no need to cutover of any existing transaction. However, there are few intercompany loans that will mature by the end of this year and some of them might be replaced by the deals referencing to the overnight risk-free rates. Having strong presence in the United States, the exposure to the USD LIBOR is considerably higher than to the GBP and CHF LIBOR ceasing at the end of this year. Therefore, the major transition is only expected over the next year, closer to the cessation of the USD LIBOR.

Urszula elaborates on the business transition: “Understanding the logic of how new instruments are going to work gives me a piece of mind for the transition. LYB never meant to be an early adopter of the change. Switching intercompany loans as first seems to be the best approach for us, because there are no corresponding derivatives needed for these products. Also, there is no dependency on the external counterparties, which makes the transition easier.”

Really achieved

LYB and Zanders are currently working on a follow-up project for the cash flow aggregation of interest in SAP. This need emerged from the new daily compounding functionality, which by default creates daily cash flow postings that are difficult to reconcile with the interest settlements. A user-friendly solution to aggregate these daily cash flows has been defined and configured and is currently being validated by the end users. This is the last step for LYB to be ready to create a first deal with daily compounding interest calculation in the system.

Urszula concludes: “The change is coming so you can choose either to embrace it or to postpone it. We decided to embrace it now. The greatest achievement of this project is that the project was executed within original timelines, without major issues and it gave the whole Treasury team confidence that the system will perform well. What needed to be achieved was really achieved. The complete solution is already implemented for the technical side.”

With house bank accounts treated as master data instead of configuration objects including the latest enhancement, the bank account subledger concept, SAP S/4HANA Bank Account Management (BAM) aims to shift responsibility of bank account management life cycle from the technical teams to the cash and banking teams.

Bank accounts can now be created and maintained by the cash and banking responsible team, giving them more control over the timing of opening or closing of an account as well as expediting the overall process and limiting the number of users involved in the maintenance of the accounts.

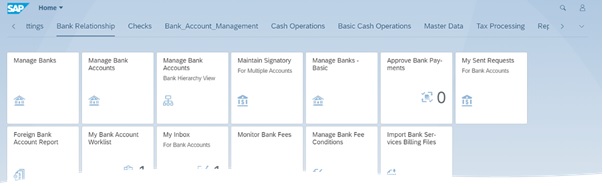

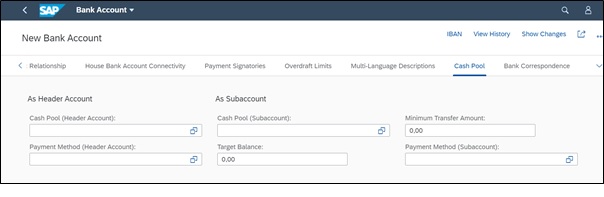

Figure 1 – Launchpad BankApplications

The advantages of using the full version of BAM are multiple, but below we highlight three of the main reasons full BAM is a must have for the companies using one or multiple SAP environments.

Flexible workflows

Maintenance of bank account data can trigger workflows based on the organization’s requirements and the approval processes in place. With the workflows the segregation of duties can be enforced when maintaining a bank account.

Even though workflows are not a new functionality in S/4HANA, the fact that workflow templates are available and can be amended by defining preconditions, step sequences and recipients improves the approval process of bank accounts.

The workflows can be created and activated as completely new ones or based on the already existing templates . You can create a new workflow by copying an existing one and updating the parameters according to the new requirements.

All the requests to release or approve bank account changes are available as of S/4HANA 2020 in the My Inbox for Bank Accounts app, the dedicated inbox app where users can check the status of each request initiated by the users themselves or sent to them and act upon.

Easy data replication

One of the challenges multiple organizations have, especially those operating various SAP environments, is data synchronization and replication. We often come across situations when banks, house banks and bank accounts are not maintained in all relevant environments creating data inconsistencies and making processes more difficult than they already are.

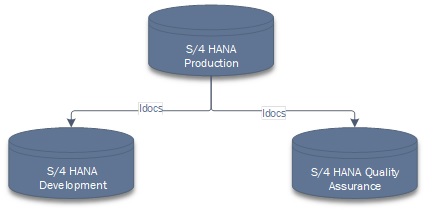

One of the ways of avoiding these types of situations is by replicating banks, house banks and bank accounts from production to quality assurance and to development environments using standard Idocs.

Figure 2 – Bank data replication in S/4 HANA

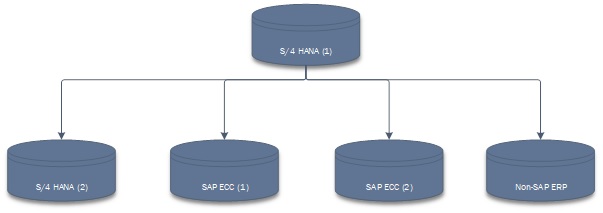

If the organization is operating on multiple SAP and non-SAP instances and running processes in a S/4 HANA side-car solution, the challenge of maintaining banks, house banks and bank accounts grows exponentially. Distributing the data via Idocs will not only keep all the systems coordinated, it will also decrease the amount of manual work and avoid situations when processes fail because of delays in keeping the data up to date in all relevant environments.

Figure 3 -Bank data replication across multiple environments

Simple way of managing cash pools

Cash pooling structures can easily be set up by the user and in this way the BAM solution is integrated with the process of making cash management transfers.

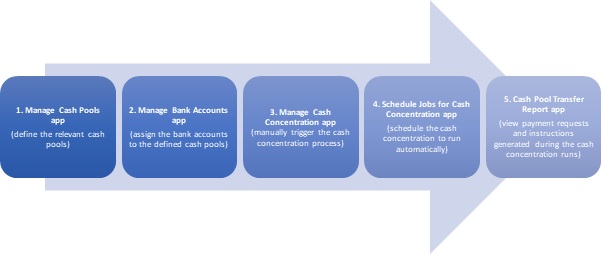

Even though the cash pooling and cash concentration in S/4HANA are managed using five different apps (shown in the figure below), the actual structure of the cash pool is defined directly in the Manage Bank Accounts app (Cash Pool tab).

Figure 4 – Five apps to manage cash pooling and cash concentration in S/4HANA

In the Cash Pool tab, the user can define the cash pool structure as per each company’s requirements. It is important to keep in mind the fact that a bank account can be assigned only to two different cash pools: once as the header account of a cash pool, and once in a different cash pool, as a subaccount.

The cash pools created in the system are not restricted to one company code but can be defined using various currency accounts belonging to multiple company codes. For each of the bank accounts included in a cash pool, a target balance as well as a minimum transfer amount can be defined in the Cash Pool tab of the Manage Bank Accounts app, with the mention that both (target balance as well as minimum transfer amounts) must be defined in the bank account currency.

During the cash concentration process, when bank transfers are generated, the payment methods defined in this tab will be picked up. Therefore, if required, two different payment methods can be assigned; the first for the structure where the bank account is acting as a header account and the second for the one where the account in scope is a subaccount. To pick them up from the drop-down list, the assigned payment methods must be initially setup in the system.

To conclude

Maintaining banks, house banks and bank accounts can be a difficult task especially in large organizations operating with different SAP and non-SAP environments. It can be time-consuming; it can involve multiple people from different parts of the organization (IT, master data, cash and banking etc.) and it can easily be prone to errors and mismatches if not correctly maintained and synchronized. Having one single source of truth for the bank accounts – which is easy to maintain, user-friendly, with appropriate controls in place and reporting capabilities, easy to replicate the data across different environments and which allows the user to create and maintain not only the bank accounts but also the cash pool structures – can save time, resources and simplify processes.

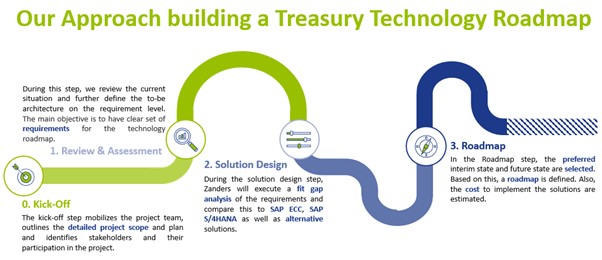

The need to formulate a treasury technology roadmap for your organization has never been more critical.

This is particularly relevant for large complex organizations that are running SAP. The SAP S/4HANA move is complex and presents great opportunities and challenges. For the treasury within these large complex organizations it does not make sense to wait for the enterprise to formulate a roadmap as then the likelihood of the treasury requirements not being properly prioritized are high.

It is in this context that Zanders provides the option to help your organization formulate a treasury technology roadmap. Driven by 27 years of experience we have built a best practice framework for treasury transformation projects. The approach we have formulated for the treasury technology roadmap ensures that we start by focusing efforts on establishing a clear set of requirements for the treasury organization and processes. Here too we have built up a sound catalogue of strategic treasury requirements which are mapped to a solid treasury business process framework, and it is against this foundation that we engage with the treasury organization to ensure we emerge with an accurate view of the specific treasury requirements. In the process we ensure these requirements are categorized according to priority and evaluated relative to current available functionality.

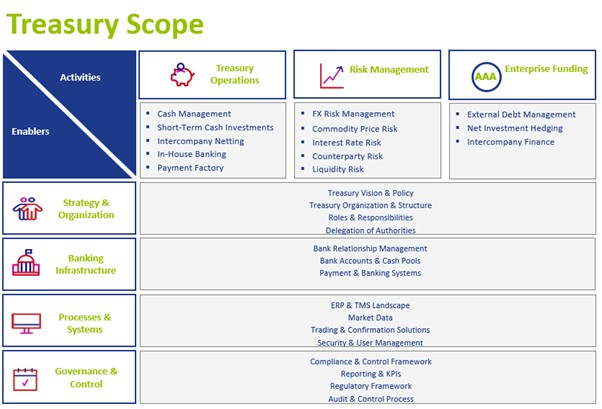

Enablers for core treasury activities

We also establish a clear scope for the roadmap based on the activities to be covered which in effect defines the processes in scope. The Zanders framework uses three core treasury activities being Treasury Operations, Risk Management and Enterprise Funding with the associated 15 underlying sub-processes that support these.

The Zanders framework then has four enablers that support these core treasury activities. These are:

- Strategy and organization

- Banking Infrastructure

- Processes and systems

- Governance and controls

Typically for a treasury technology roadmap engagement, the focus is on the processes and systems enabler, but we will also take into the strategy and organization in formulating the scope of the assessment here the geographic and organizational scope is established and confirmed. For banking infrastructure, the banks, bank accounts and payment type scope is established.

Figure 1: Treasury Roadmap; Driven by 27 years of experience we have built a best practice framework for Treasury Transformation projects. Based on this framework and considering what has been requested by clients, we propose the following approach to build a well-defined Treasury Technology Roadmap.

Figure 2 – Treasury scope; The starting point for kicking off the roadmap is defining the functional scope in line with the three core Treasury activities (Treasury Operations, Risk Management, Enterprise Funding) and the relevant underlying 15 sub-activities.

Fit-gap analysis of requirement

The next step in the process is solution design where we perform a fit-gap analysis of requirement and compare this to the existing and proposed treasury technology platforms. This analysis can be tailored to exclusively focus on SAP treasury solutions or include suitable alternative technology platforms. In addition, with the increase in available add-on solutions in the market this analysis can also be expanded to explore and expose the relevant technology solutions that fit the unique treasury requirements based on the prioritization established.

Where the first step of the process ensured an accurate understanding of the organization’s treasury requirements, this step ensures that the treasury organization is exposed to a focused set of relevant solutions that meet these requirements.

A further important consideration is on which SAP system within the organization the treasury requirements will be implemented. Here the many available deployment options need to be considered and evaluated including S/4 HANA side car options (Cloud or On Premise), deployment in a single central instance and the likes of Central Finance architecture and approach.

Meeting all objectives

Finally, the roadmap step is where the analysis is brought together to settle on relevant alternative options that meet both treasury and the broader enterprise’s strategic long-term objectives. For these viable technology options realistic implementation timeframes are estimated and a framework for total cost of ownership is established. This ensures that the basis for the business case is established and the parameters for the various options are clearly articulated.

In such a way the treasury organization is able to help lead rather than follow at this crucial time and hence ensure that the treasury technology requirements are included in the overall enterprise technology roadmap and a measure of order and clarity is brought into the formulation of the enterprise transformation plans.

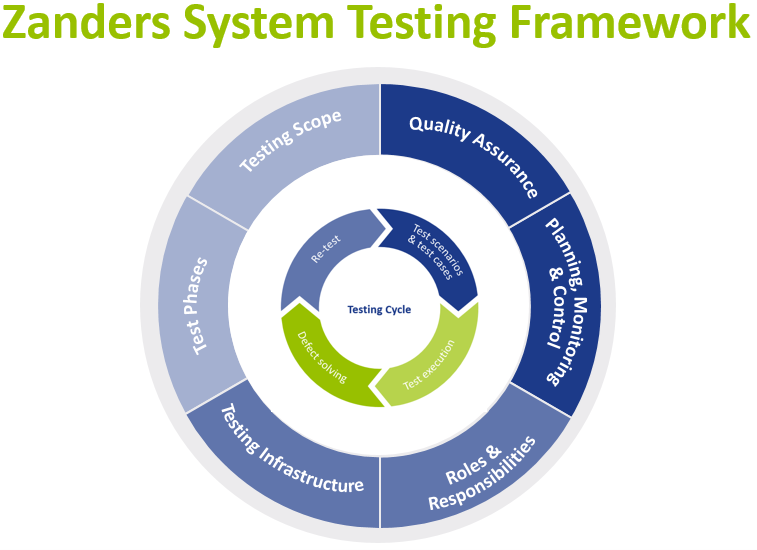

Fail Fast, Fail Early, Fail Often

Testing is a critical activity in any implementation, and it has a significant impact in any overall project success. However, testing often takes longer than planned, due to poor execution or unexpected issues that arise in a later project stage. Such problems usually occur when not all the variables necessary for a successful test journey have been considered.

To avoid these issues, we have defined a testing framework to help you identify an optimal testing strategy and approach. The framework depicts building blocks that need to be present and considered for effective and successful system testing where project size, project scope, project approach and resource availability need to be taken into consideration.

This article further describes each of these building blocks and it will outline factors and principles that help to achieve effective testing and result in a sound system implementation.

Testing Strategy – a top-down approach

Before starting to look at each area of the testing framework, the testing strategy needs to be defined. The strategy, based on project size and scope, should determine what the testing key principles are:

- High level scope

- Proposed phases and duration

- Business engagement and involvement

- Testing governance model

- Key benefits and risks mitigated by each testing phase

- When and how to determine exit criteria’s

The testing strategy will then underpin the detailed plan and definition of each one of our testing building blocks.

Roles & Responsibilities

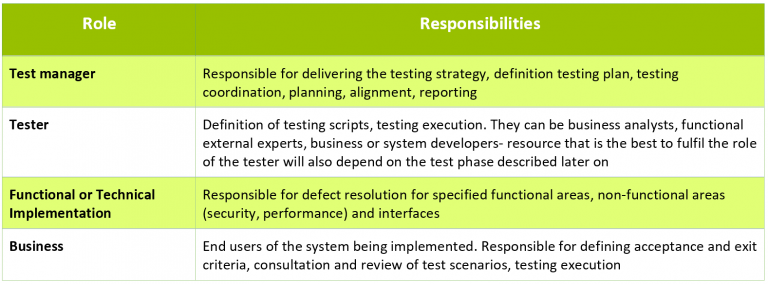

Clear establishment of roles and responsibilities (RACI matrix) is key to the effective testing. This ensures that the right profiles are assigned to each area, and that there is clear ownership for each deliverable. This is key to have a realistic estimation of effort and plan. Some examples of roles and responsibilities include:

In smaller scale projects, the above roles may be combined under the same resource, while in larger projects more resources will be needed to fulfil a single role. One of the key principles with regards to resourcing is the early involvement of business in testing. Early involvement of the business in testing provides the following benefits:

- Focus on business value items and critical areas, which ultimately saves cost and time and ensures early risk mitigation.

- Continuous improvement and assurance that project’s overall objective and business case is met.

- Business embraces the process and organizational changes faster.

- Critical areas are tested sooner, and critical issues are solved earlier.

- Establishment of the business ownership of the system being implemented.

Planning, Monitoring & Control

Plans need to lay down testing scope (test scenarios and test cases), number and type of resources and time needed for preparation and execution for each test phase. It should also take into consideration the system development stage and other entry criteria, as well as an estimate of the defects and defect resolution time.

Around monitoring and control it is essential that test execution itself is administered in a consistent manner. There are software solutions that can support the whole testing process and its administration. In any case, the progress of testing and the status of the progress of defect handling need to be trackable. At a minimum, it is recommended to track and gather evidence for the following:

- Test scenarios and test cases, including testers and timelines.

- Overview of defects, including root cause, severity classification, resolution timelines and person responsible for fixing the defect.

- Test execution evidence, including actual execution timelines, pass/fail status, screenshots, and other evidence.

It is also important to report daily on the progress of each test phase, as this enables project managers to mitigate deviations from the plan in the timely manner. Progress reporting will provide transparency, and it helps to increase confidence of the involved stakeholders.

Testing Scope

Testing should follow predetermined test scenarios and test cases. Test scenarios describe what functionality of the system is to be tested (e.g. input FX trade request, approve FX trade request). Test cases describe variations that should be tested, such as deal types or events (FX spot trade, FX forward trade, unwind, for example).

All test scenarios and test cases should be linked to the initial business requirements and should be created, reviewed, and approved by the business. Business can help identifying value items and risk areas that should take priority for testing. This allows priority and risk to be assigned to different functionalities, processes, and test scenarios.

Quality Assurance

Quality assurance while testing is two-fold. The project should assure both the quality of the system being implemented, as well as the quality of the test execution.

Essentially, testing activity validates whether what was developed provides an adequate outcome. Expected results are based on the requirements laid out in the system design documentation. It is important that business is involved in definition and review of the expected result.

Setting the quality for testing execution involves defining relevant criteria. First, entry criteria are set before each test phase, such as completion of the (piece of) system development, environment setup, access to the environment for testers and availability of relevant data. Second, exit criteria need to be established, which will determine when the test phase can be successfully exited.

Furthermore, acceptable variances and thresholds (e.g. legacy system vs new system portfolio valuations due to different valuation methodologies or rounding differences) need to be defined with the business beforehand and included in the expected results and acceptance criteria.

Testing Infrastructure

In any system implementation, it is standard to operate with at least three system environments. It is also common to deploy a multiple test environment, e.g. an environment for the ST/SIT testing and a test environment dedicated to UAT test phase.

Test automation should be included, or at least considered, in any larger system implementation projects. When selecting processes to automate testing we look for:

- Repetitive tests (e.g. deal capture, master data creation/change/deletion).

- Tests that tend to cause human error (e.g. market rate manual upload).

- Tests that require multiple data sets (e.g. master data uploads).

- Frequently used functionality that introduces high risk conditions (e.g. payment runs).

- Tests that are impossible to perform manually (e.g. performance and non-functional requirements tests).

When analyzing what to automate, it is very important to take a strategic and broad view. If testing of some processes or functionalities can be automated, it is probable that after system deployment these processes or functionalities can also be automated in day-to-day execution.

Most of the existing tools that can be used for automation are not expensive and in some cases in-house expertise can be used (e.g. RPA). Examples of such solutions are mentioned below:

- Robotic Process Automation (RPA) for process testing and validation.

- Standard automation testing tools (e.g. Selenium, TestComplete) for functional and non-functional testing.

- Non-functional Requirements and performance testing tools (e.g. Splunk).

Some treasury management systems have also started to provide their own tools, embedded in their systems (e.g, scripting).

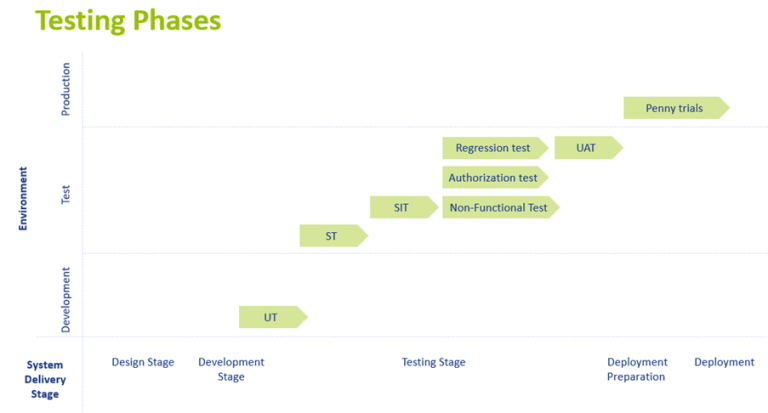

Testing Phases

There are several unique testing phases with specific objectives. The figure below shows these testing phases across time (system delivery stage) and illustrates in what system environment the testing should be performed. This figure is based on the conventional Waterfall (phased) project approach.

UT (Unit Test)

This is a first test performed and it follows straight after completion of system configuration and setup. The purpose of the UT is to initially confirm both technical and functional requirements. It tests a functionality on a stand-alone basis.

ST (System Test)

System Testing focuses on a combination of unit tests (testing several build components) in a specific process flow and it is performed in the test environment. For example, for back-to-back FX dealing, ST will consist of FX trade request input, trade request approval, FX trade execution, deal creation and mirroring, payment request creation and accounting postings.

SIT (System Integration Test)

The purpose of SIT is to test end-to-end processes including interfaces with connected systems and applications. SIT is also performed in the test environment and it requires availability of the test environments from the connected systems and applications.

Authorizations test

Most of the systems will require authorization setup for different system users, next to the workflow configuration. Authorizations determine what activities a specific user can perform in the system.

Non-Functional Test

Non-Functional Testing is a technical test, typically executed by technical resource. It tests system performance, security and other non-functional requirements.

UAT (User Acceptance Test)

UAT is the one of the last tests before technical and business go-live. It is a functional test, and it should be executed by the key users of the system. Generally, this is the longest test period. UAT test scenarios include workflow testing, authorization testing, negative test cases and business continuity plan activities. This test phase also includes the largest variation of test cases.

Penny trials phase

This testing phase is mostly applicable when the project also includes commercial or trade settlements. Penny trials are part of the system deployment preparation and they are performed in the production ‘live’ environment. The actual end to end deal process including payment and confirmation will be executed with low value transactions (e.g. a $10 spot deal).

Parallel Run

It can be beneficial to operate a system in the parallel run mode at least for some period. Parallel run basically replicates day-to-day activities in the system being implemented in parallel to the legacy system and processes.

Adopting System Testing Framework in Agile Projects

In recent years, organizations have increasingly adopted an agile project approach for system implementation. An agile approach would split system development in smaller products that could be incrementally deployed (in a production or testing environment).

System testing framework can be and should be adopted in the agile or mixed project approach as well. Most of the building blocks for successful testing described here are agnostic to the project approach given, some tailoring of the specific factors to the format of agile approach is executed. As system delivery is split into smaller deployable products in agile approach, test phases should follow the same design. That means that instead of a single SIT period, SIT would be executed after completion of each incremental system development (e.g. back-to-back dealing). Nevertheless, it is notable to mention that in agile projects there needs to also be several testing phases, tested by different resources.

Conclusion: Failure is success in progress

There is no one-size-fits-all around testing. The project size and scope, resource availability, internal and external skillsets and project methodology will determine how to approach each testing phase. Nevertheless, having the right system testing framework to guide you through a project is essential to any successful project. This will ensure that you fail fast, early, often during early testing phases, reducing go live delivery and operational risks.

Climate and environmental changes are viewed among the most important risks in society at present.

As the financial sector is key for the transition towards a low-carbon and more circular economy, financial institutions have to deal with climate-related and environmental financial risks (C&E risks). At the same time, the increased importance of these C&E risks also presents new business opportunities for the financial sector. Therefore, to support banks in their self-assessment and action plans, Zanders developed a Scan & Plan Solution on C&E risks.

According to the 2021 World Economic Forum Global Risk Report1, extreme weather, climate action failure, human environmental damage and biodiversity loss are ranked as four of the top five global risks by highest likelihood and four of the six global risks with the largest impact. It is not surprising that over the past years, numerous articles on C&E risks have been published and many initiatives have been taken to identify, measure and manage these risks. The Paris Agreement2, the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development3 and more recently the European Green Deal4 are the main examples of international governmental responses to address C&E risks.

The financial sector is considered key for the transition towards a low-carbon and more circular economy. This is illustrated by the fact that the European Central Bank (ECB) has identified climate-related risks as a key risk driver for the euro area banking system in their Single Supervisory Mechanism Risk Map5. At the same time, the increased importance of C&E risks also presents new business opportunities for the financial sector, such as providing sustainable financing solutions and offering new financial instruments that facilitate C&E risk management. To illustrate, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change6 (IPCC) estimates that the required investment for alignment with the Paris Agreement would be at least $3.5tn per year until 2050 for the energy sector alone.

To address C&E risks, the ECB published a Guide on climate-related and environmental risks7 for banks that describes the ECB’s supervisory expectations related to risk management and disclosure. Banks are required by the ECB to perform a self-assessment with respect to the supervisory expectations and to draft an action plan in 2021. The self-assessments and plans will subsequently be reviewed and challenged by the ECB as part of the supervisory dialogue. In 2022, the ECB will conduct a full supervisory review of bank’s practices related to C&E risks.

The Zanders Scan & Plan Solution provides clear insights into gaps with the ECB expectations and proposes practical actions that are tailored to a bank’s nature, scale and complexity. This article provides a brief explanation of C&E risks, outlines a few specific ECB supervisory expectations and elaborates on the Solution.

Definition of C&E risk

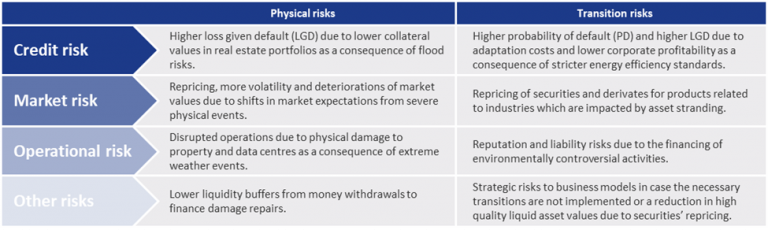

Financial risks from climate and environmental change arise from two primary risk categories:

- Physical risks. The first risk category concerns physical risks caused by acute (direct events) or chronic (longer-term events which cause gradual deterioration) C&E events. Examples of acute events are floods, wildfires and heatwaves, whereas chronic events relate to the likes of rising sea levels, acidity and biodiversity losses, for example.

- Transition risks. The second risk category comprises transition risks resulting from the process of moving towards a low-carbon economy. Changes in policy, regulation, technology, market sentiment and consumer sentiment could destabilize markets, tighten financial conditions and lead to procyclicality of losses.

These two risk categories are distinct from other risk categories in the following aspects: 1) they have a correlated and non-linear impact on all business lines, sectors and geographies, 2) they have a long-term nature and 3) the future impact is largely dependent on short-term actions. The risk categories are, among others, drivers of credit, market and operational risk, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Examples of the impact of physical risks and transition risks on traditional risk types from the ECB Guide on climate-related and environmental risks.

ECB Supervisory Expectations

In the Guide on climate-related and environmental risks7, published in November 2020, the ECB explains that banks are expected to reflect C&E risks as drivers of existing risk categories (e.g., credit risk, market risk, operational risk) rather than as a separate risk type. This indicates that not only efforts should be made by banks to develop risk management practices related to C&E risks but that these practices should also be integrated in existing risk management frameworks, models and policies.

The ECB Guide covers four main areas. First, in relation to ‘business models and strategy’, the ECB expects banks to understand the impact of C&E risks on their business environment and integrate C&E risks in their business strategy. Secondly, the guide addresses ‘governance and risk appetite’. The ECB expects a bank’s management to include C&E risks in the risk appetite framework, assign responsibilities related to C&E risks to the three lines of defense and establish internal reporting. Thirdly, in relation to ‘risk management’, the ECB expects that banks integrate C&E risks into their existing risk management framework. Finally, regarding ‘disclosures’, the ECB expects banks to disclose meaningful information and metrics on C&E risks. The four above-mentioned areas are covered in 13 expectations, which are in turn further divided in 46 sub-expectations. Banks are required by the ECB to perform a self-assessment with respect to the supervisory expectations and to draft an action plan in 2021. The self-assessments and plans will subsequently be reviewed and challenged by the ECB as part of the supervisory dialogue. The ECB recommends National Competent Authorities, in their supervision of less significant institutions, to apply these expectations proportionate to the nature, scale and complexity of the bank’s activities.

Zanders has thoroughly analyzed all (sub)-expectations and has highlighted a few specific expectations including possible actions below.

Expectation 4.2: Institutions are expected to develop appropriate key risk indicators (KRI) and set appropriate limits for effectively managing climate-related and environmental risks in line with their regular monitoring and escalation arrangements.

Here, the ECB expects institutions to monitor and report their exposures to C&E risks based on current data and forward-looking estimations. In addition, institutions are expected to assign quantitative metrics to C&E risks. It is however acknowledged that, since definitions, taxonomies and methodologies are still under development, qualitative metric or proxy data can be used as long as specific quantitative metrics are not yet available. The ECB deems that the metrics should reflect the long-term nature of climate change, and explicitly consider different paths for temperature and greenhouse gas emissions. Finally, the ECB expects institutions to define limits on the metrics based on the risk appetite regarding C&E risks.

This expectation has various elements to it, and Zanders has defined as the most important and first step to identify the internal and external data availability related to C&E risks. If the data availability allows it, an institution should set up quantitative metrics and limits on these metrics that reflect C&E risks. A first step to achieve this would be to define several firmwide KRIs, for example by limiting the carbon emission of the whole portfolio in line with the Paris Agreement2 or other (inter)national climate agreements. These KRIs can then be cascaded down to business lines and/or portfolios, such as limiting the exposure to specific sectors with large carbon footprints or substantial use of water. If the current data availability does not allow for quantitative metrics, the bank should identify which data is still lacking and assess ways to collect this data from internal data sources or external data providers in the course of time. In the meantime, qualitative metrics or proxies could be developed such as a qualitative score for the sophistication of the climate strategy of large corporates in the portfolio.

Should a bank already have some metrics in place, Zanders advises to evaluate if these metrics sufficiently cover all material physical and transition C&E risks that the bank is expected to face and if there are ways to increase the sophistication of these metrics, for example by including forward-looking estimations. Finally, Zanders advises banks to create a monitoring procedure to ensure that these metrics and their limits are evaluated regularly.

Expectation 8.1: Climate-related and environmental risks are expected to be included in all relevant stages of the credit-granting process and credit processing.

In this expectation, the ECB underlines that banks should identify and assess material factors that affect the default risk of loan exposures. The quality of the client’s own management of C&E risks may be taken into account in this case. In addition, banks are expected to consider changes in the credit risk profiles based on sectors and geographical areas.

The way to address this expectation is highly dependent on the nature of the bank, on the existing credit granting process and on the availability of data. Some examples of including C&E risk in the credit granting process in a qualitative way, which Zanders has observed in the market, are the development of shadow PD models that trigger mitigating actions in case of large discrepancies with the regular PDs, or the introduction of a scorecard based on quantitative as well as qualitative aspects.

It should be noted that these and other solutions are not mutually exclusive and that multiple approaches can be adopted for different parts of the portfolio. Also, the efforts for several individual expectations can be combined. For example, taking C&E risks into account in the credit granting process could also be linked to the qualitative and quantitative metrics set as part of expectation 4.2 (see above). The quality of the client’s own management of C&E risks can for instance be measured based on the qualitative score for the climate strategy sophistication of large corporates mentioned above.

Expectation 11: Institutions with material climate-related and environmental risks are expected to evaluate the appropriateness of their stress testing, with a view to incorporating them into their baseline and adverse scenarios.

This expectation indicates that banks should evaluate the appropriateness of their stress testing in relation to C&E risks. In this evaluation, the bank should take into account the following considerations: i) how will the bank be affected by physical and transition risks, ii) how will C&E risks evolve under various scenarios (thereby taking into account that these risks may not fully be reflected in historical data), and iii) how may C&E risks materialize in the short-, medium- and long-term. Based on these considerations and on scientific climate change pathways as well as on assumptions that fit with their risk profile and individual specification, banks should incorporate C&E risks in their baseline and adverse scenarios.

To address this recommendation, Zanders advises banks to first identify C&E risks scenarios with different severities based on the materiality of C&E risks for the bank. Examples of this include early or late transition to a low-carbon economy (transition risk), introduction of a carbon tax (transition risk) or staying below or above a 2°C temperature increase (physical risk). These scenarios could be based on scientific scenarios from the IPCC8 or the International Energy Agency9. The next step is to translate these scenarios into macro-economic variables, such as GDP, inflation and loan valuations, over a range of relevant sectors and geographies. Since there is not yet a single methodology to do this, banks need to be creative and combine new qualitative and quantitative approaches with existing modeling methodologies.

Zanders Scan & Plan Solution

To manage C&E risks, to seize new business opportunities and to meet the regulatory expectations related to C&E risks, it is crucial for banks to have transparency about their exposure to these risks. To support banks with this, the Zanders Scan & Plan Solution is available. The Scan assesses the gaps between the bank’s current practices and each of the expectations in the ECB guide. These gaps are scored based on a pre-defined scoring system and are shown in a heatmap that is easy to interpret. Subsequently, the Plan proposes possible actions to close the identified gaps. These possible actions will be tailored to the nature, scale, and complexity of the bank and to the level of sophistication of the bank in the field of C&E risks. The Scan & Plan will be provided in the form of a detailed report.

Zanders has previously supported clients on topics related to climate change, published market insights and supported research. In addition, Zanders has broad experience in supporting clients in each of the areas of the ECB guide: business models and strategy, governance and risk appetite, risk management and disclosure. Hence, Zanders is in an excellent position to also support banks with the implementation of the proposed actions from the Scan & Plan or with shaping new business activities related to C&E risks.

To learn more about the Zanders Scan & Plan solution and how Zanders can support your institution with managing C&E risks, please contact Petra van Meel, Marije Wiersma or Pieter Klaassen.

References

1) http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2021.pdf

2) https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

3) https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

4) https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

5) https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/ra/html/ssm.ra2021~edbbea1f8f.en.html#toc1

6) https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2019/02/SR15_Chapter4_Low_Res.pdf

7) https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.202011finalguideonclimate-relatedandenvironmentalrisks~58213f6564.en.pdf

8) https://www.ipcc.ch/report/emissions-scenarios/

9) https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-model/sustainable-development-scenario

As sustainability is gaining momentum as a business priority, numerous corporates are re-assessing their business models and strategic goals.

One of the key subjects in this re-assessment is the implementation of tangible and transparent Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors into the business.

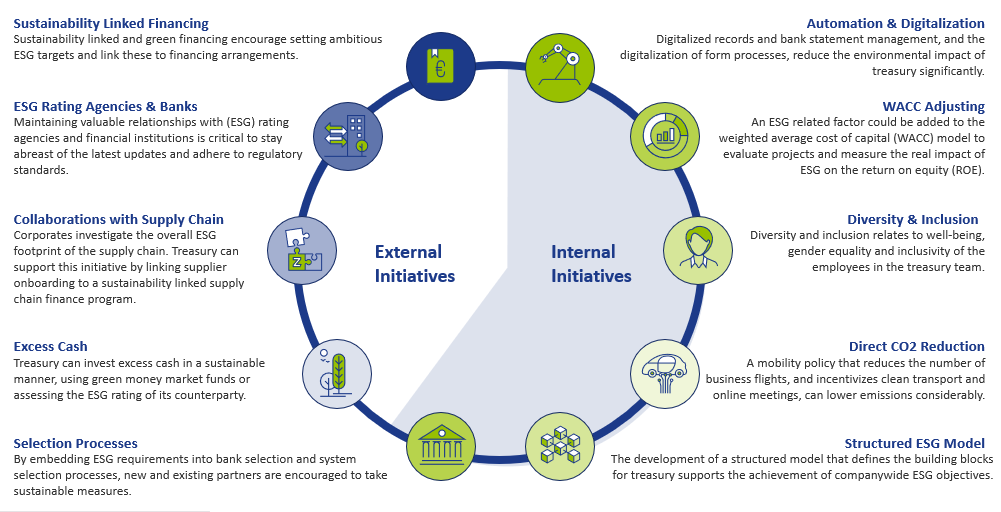

Treasury can drive sustainability throughout the company from two perspectives, namely through initiatives within the Treasury function and initiatives promoted by external stakeholders, such as banks, investors, or its clients. When considering sustainability, many treasurers first port of call is to investigate realizing sustainable financing framework. This is driven by the high supply of money earmarked for sustainable goals. However, besides this external focus, Treasury can strive to make its own operations more sustainable and, as a result, actively contribute to company-wide ESG objectives.

Figure 1: ESG initiatives in scope for Treasury

Treasury holds a unique position within the company because of the cooperation it has with business areas and the interaction with external stakeholders. Treasury can leverage this position to drive ESG developments throughout the company, stay informed of latest updates and adhere to regulatory standards. This article shows how Treasury can become a sustainable support function in its own right, highlights various initiatives within and outside the Treasury department and marks the benefits for Treasury – on top of realising ESG targets.

Internal initiatives

Automation and digitalization drive certain environmental initiatives within the Treasury department. Full digitalized records and bank statement management and the digitalization of form processes reduce the adverse environmental impact of the Treasury department. Besides reducing Treasury’s environmental footprint, digitalization improves efficiency of the Treasury team. By reducing the number of manual, cumbersome operational activities, time can be spent on value-adding activities rather than operational tasks.

Another great example of how Treasury can contribute to the ESG goals of the company, is to incorporate ESG elements in the capital allocation process. This can be done by adding ESG related risk factors to the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) or hurdle investment rates. By having an ESG linked WACC, one can evaluate projects by measuring the real impact of ESG on the required return on equity (ROE). By adjusting the WACC to, for example, the level of CO2 that is emitted by a project, the capital allocation process favours projects with low CO2 emissions.

An additional internal initiative is the design of a mobility policy with the objective to lower CO2 emissions. On one hand, this relates to decreasing the amount of business trips made by the Treasury department itself. On the other hand, it relates to the reduction of business travel by stakeholders of treasury such as bankers, advisors and system vendors. A framework that offsets the added value of a real-life meeting against the CO2 emission is an example of a measure that supports CO2 reduction on both sides. Such a framework supports determination whether the meeting takes place online or in person.

Furthermore, embedding ESG requirements into bank selection, system selection and maintenance processes is a valuable way of encouraging new and existing partners to undertake ESG related measures.

When it comes to social contributions, the focus could be on the diversity and inclusion of the Treasury department, which includes well-being, gender equality and inclusivity of the employees. Pursuing these policies can increase the attractiveness of the organization when hiring talent and make it easier to retain talent within the company, which is also beneficial to the Treasury function.

The development of a structured model that defines the building blocks for Treasury to support the achievement of companywide ESG objectives is a governance initiative that Treasury could undertake. An example of such a model is the Zanders Treasury and Risk Maturity Model, which can be integrated in any organization. This framework supports Treasury in keeping track of its ESG footprint and its contribution to company-wide sustainable objectives. In addition, the Zanders sustainability dashboard provides information on metrics and benchmarks that can be applied to track the progress of several ESG related goals for Treasury. Some examples of these are provided in our ‘Integration of ESG in treasury’ article.

External initiatives

Besides actions taken within the Treasury department, Treasury can boost company-wide ESG performance by leveraging their collaboration with external stakeholders. One of these external initiatives is sustainability linked financing, which is a great tool to encourage the setting of ambitious, company-wide ESG targets and link these to financing arrangements. Examples of sustainability linked financing products include green loans and bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and social bonds. To structure sustainability-linked financing products, corporates often benefit from the guidance of external parties when setting KPIs and ambitious targets and linking these to the existing sustainability strategy. Besides Treasury’s strong relationships with banks, retaining good relationships with (ESG) rating agencies and financial institutions is critical to stay abreast of the latest updates and adhere to regulatory standards. Additionally, investing excess cash in a sustainable manner, using green money market funds or assessing the ESG rating of counterparties, is an effective way of supporting sustainability.

Apart from financing instruments, Treasury can drive the ESG strategy throughout the organization in other ways. Treasury can seek collaborations with business partners to comply with ESG targets, which is another effective manner to achieve ESG related goals throughout the supply chain. An increasing number of corporates is looking to reduce the carbon footprint of their supply chain, for which collaboration is essential. Treasury can support this initiative by linking supplier onboarding on its supply chain finance program to the sustainability performance of suppliers.

To conclude

As developments in ESG are rapidly unfold9ing, Zanders has started an initiative to continuously update our clients to stay ahead of the latest trends. Through the knowledge and network that we have built over the years, we will regularly inform our clients on ESG trends via articles on the news page on our website. The first article will be devoted to the revision of the Sustainability Linked Loan Principles (SLLP) by the Loan Market Association (LMA) and its American and Asian equivalents.

We are keen to hear which topics you would like to see covered. Feel free to reach out to Joris van den Beld or Sander van Tol if you have any questions or want to address ESG topics that are on your agenda.

After the long-acknowledged fact that global warming has catastrophic consequences, it is also increasingly recognized that climate change will impact the financial industry.

The Bank of England is even of the opinion that climate change represents the tragedy of the horizon: “by the time it is clear that climate change is creating risks that we want to reduce, it may already be too late to act” [1]. This article provides a summary of the type of financial risks resulting from climate change, various initiatives within the financial industry relating to the shift towards a low-carbon economy, and an outlook for the assessment of climate change risks in the future.

At the December 2015 Paris Agreement conference, strict measures to limit the rise in global temperatures were agreed upon. By signing the Paris Agreement, governments from all over the world committed themselves to paving a more sustainable path for the planet and the economy. If no action is taken and the emission of greenhouse gasses is not reduced, research finds that per 2100, the temperature will have increased by 3°C to 5°C2.. Climate change affects the availability of resources, the supply and demand for products and services and the performance of physical assets. Worldwide economic costs from natural disasters already exceeded the 30-year average of USD 140 billion per annum in seven out of the last ten years. Extreme weather circumstances influence health and damage infrastructure and private properties, thereby reducing wealth and limiting productivity. According to Frank Elderson, Executive Director at the DNB, this can disrupt economic activity and trade, lead to resource shortages and shift capital from more productive uses to reconstruction and replacement3.

According to the Bank of England, financial risks from climate change come down to two primary risk factors4:

Increasing concerns about climate change has led to a shift in the perception of climate risk among companies and investors. Where in the past analysis of climate-related issues was limited to sectors directly linked to fossil fuels and carbon emissions, it is currently being recognized that climate-related risk exposures concern all sectors, including financials. Banks are particularly vulnerable to climate-related risks as they are tied to every market sector through their lending practices.

Financial risks

- Physical risks. The first risk factor concerns physical risks caused by climate and weather-related events such as droughts and a sea level rise. Potential consequences are large financial losses due to damage to property, land and infrastructure. This could lead to impairment of asset values and borrowers’ creditworthiness. For example, as of January 2019, Dutch financial institutions have EUR 97 billion invested in companies active in areas with water scarcity5. These institutions can face distress if the water scarcity turns into water shortages. Another consequence of extreme climate and weather-related events is the increase in insurance claims: in the US alone, the insurance industry paid out USD 135 billion from natural catastrophes in 2017, almost three times higher than the annual average of USD 49 billion.

- Transition risks. The second risk factor comprises transition risks resulting from the process of moving towards a low-carbon economy. Revaluation of assets because of changes in policy, technology and sentiment could destabilize markets, tighten financial conditions and lead to procyclicality of losses. The impact of the transition is not limited to energy companies: transportation, agriculture, real estate and infrastructure companies are also affected. An example of transition risk is a decrease in financial return from stocks of energy companies if the energy transition undermines the value of oil stocks. Another example is a decrease in the value of real estate due to higher sustainability requirements.

These two climate-related risk factors increase credit risk, market risk and operational risk and have distinctive elements from other risk factors that lead to a number of unique challenges. Firstly, financial risks from physical and transition risk factors may be more far-reaching in breadth and magnitude than other types of risks as they are relevant to virtually all business lines, sectors and geographies, and little diversification is present. Secondly, there is uncertainty in timing of when financial risks may be realized. The possibility exists that the risk impact falls outside of current business planning horizons. Thirdly, despite the uncertainty surrounding the exact impact of climate change risks, combinations of physical and transition risk factors do lead to financial risk. Finally, the magnitude of the future impact is largely dependent on short-term actions.

Initiatives

Many parties in the financial sector acknowledge that although the main responsibility for ensuring the success of the Paris Agreement and limiting climate change lies with governments, central banks and supervisors also have responsibilities. Consequently, climate change and the inherent financial risks are increasingly receiving attention, which is evidenced by the various recent initiatives related to this topic.

Banks and regulators

The Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) is an international cooperation between central banks and regulators6. NGFS aims to increase the financial sector’s efforts to achieve the Paris climate goals, for example by raising capital for green and low-carbon investments. NGFS additionally maps out what is needed for climate risk management. DNB and central banks and regulators of China, Germany, France, Mexico, Singapore, UK and Sweden were involved from the start of NGFS in 2017. The ECB, EBA, EIB and EIOPA are currently also part of the network. In the first progress report of October 2018, NGFS acknowledged that regulators and central banks increased their efforts to understand and estimate the extent of climate and environmental risks. They also noted, however, that there is still a long way to go.

In their first comprehensive report of April 2019, NGFS drafted the following six recommendations for central banks, supervisors, policymakers and financial institutions, which reflect best practices to support the Paris Agreement7:

- Integrating climate-related risks into financial stability monitoring and micro-supervision;

- Integrating sustainability factors into own-portfolio management;

- Bridging the data gaps by public authorities by making relevant data to Climate Risk Assessment (CRA) publicly available in a data repository;

- Building awareness and intellectual capacity and encouraging technical assistance and knowledge sharing;

- Achieving robust and internationally consistent climate and environment-related disclosure;

- Supporting the development of a taxonomy of economic activities.

All these recommendations require the joint action of central banks and supervisors. They aim to integrate and implement earlier identified needs and best practices to ensure a smooth transition towards a greener financial system and a low-carbon economy. Recommendations 1 and 5, which are two of the main recommendations, require further substantiation.

- The first recommendation consists of two parts. Firstly, it entails investigating climate-related financial risks in the financial system. This can be achieved by (i) mapping physical and transition risk channels to key risk indicators, (ii) performing scenario analysis of multiple plausible future scenarios to quantify the risks across the financial system and provide insight in the extent of disruption to current business models in multiple sectors and (iii) assessing how to include the consequences of climate change in macroeconomic forecasting and stability monitoring. Secondly, it underlines the need to integrate climate-related risks into prudential supervision, including engaging with financial firms and setting supervisory expectations to guide financial firms.

- The fifth recommendation stresses the importance of a robust and internationally consistent climate and environmental disclosure framework. NGFS supports the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD8) and urges financial institutions and companies that issue public debt or equity to align their disclosures with these recommendations. To encourage this, NGFS emphasizes the need for policymakers and supervisors to take actions in order to achieve a broader application of the TCFD recommendations and the growth of an internationally consistent environmental disclosure framework.

Future deliverables of NGFS consist of drafting a handbook on climate and environmental risk management, voluntary guidelines on scenario-based climate change risk analysis and best practices for including sustainability criteria into central banks’ portfolio management.

Asset managers

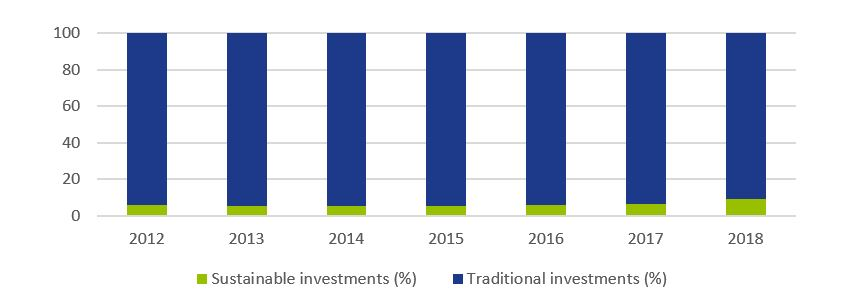

To achieve the climate goals of the Paris Agreement, €180 billion is required on an annual basis5. It is not possible to acquire such a large amount from the public sector alone and currently only a fraction of investor capital is being invested sustainably. Research from Morningstar shows that 11.6% of investor capital in the stock market and 5.6% in the bond market is invested sustainably9. Figure 1 shows that even though the percentage of capital invested in sustainable investment funds (stocks and bonds) is growing in recent years, it is still worryingly low.

Figure 1: Percentage of invested capital in Europe in traditional and sustainable investment funds (shares and bonds). Source: Morningstar [9].

The current levels of investment are not enough to support an environmentally and socially sustainable economic system. As a result, the European Commission (EC) has raised four initiatives through the Technical Expert Group on sustainable finance (TEG) that are designed to increase sustainable financing10. The first initiative is the issuance of two kinds of green (low-carbon) benchmarks. Offering funds or trackers on these indices would lead to an increase in cash flows towards sustainable companies. Secondly, an EU taxonomy for climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation has been developed. Thirdly, to enable investors to determine to what extent each investment is aligned with the climate goals, a list of economic activities that contribute to the execution of the Paris Agreement has been drafted. Finally, new disclosure requirements should enhance visibility of how investment firms integrated sustainability into their investment policy and create awareness of the climate risks the investors are exposed to.

Insurance firms

Within the insurance sector, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) requires insurers to follow a strategic approach to manage the financial risks from climate change. To support this, in July 2018, the Bank of England (BoE) formed a joint working group focusing on providing practical assistance on the assessment of financial risks resulting from climate changes. In May 2019, the working group issued a six-stage framework that helps insurers in assessing, managing and reporting physical climate risk exposure due to extreme weather events11. Practical guidance is provided in the form of several case studies, illustrating how considering the financial impacts can better inform risk management decisions.

Authorities

Another initiative is the Climate Financial Risk Forum (CFRF), a joint initiative of the PRA and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)12. The forum consists of senior representatives of the UK financial sector from banks, insurers and asset managers. CFRF aims to build capacity and share best practices across financial regulators and the industry to enhance responses to the financial climate change risks. The forum set up four working groups focusing on risk management, scenario analysis, disclosure and innovation. The purpose of these working groups, which consist of CFRF members as well as other experts such as academia, is to provide practical guidance on each of the four focus areas.

Current status and outlook

On 5 June 2019, the TCFD published a Status Report assessing a disclosure review on the extent to which 1,100 companies included information aligned with these TCFD recommendations in their 2018 reports. The report also assessed a survey on companies’ efforts to live up to TCFD recommendations and users’ opinion on the usefulness of climate-related disclosures for decision-making13. Based on the disclosure review and the survey, TCFD concluded that, while some of the results were encouraging, not enough companies are disclosing climate change-linked financial information that is useful for decision-making. More specifically, it was found that:

- “Disclosure of climate-related financial information has increased, but is still insufficient for investors;

- More clarity is needed on the potential financial impact of climate-related issues on companies;

- Of companies using scenarios, the majority do not disclose information on the resilience of their strategies;

- Mainstreaming climate-related issues requires the involvement of multiple functions.”

Further, the BoE finds that despite the progress, there is still a long way to go: while many banks are incorporating the most immediate physical risks to their business models and assess exposures to transition risks, many of them are not there yet in their identification and measurement of the financial risks. They stress that governments, financial firms, central banks and supervisors should work together internationally and domestically, private sector and public sector, to achieve a smooth transition to a low-carbon economy. Mark Carney, Governor of the BoE, is optimistic and argues that, conditional on the amount of effort, it should possible to manage the financial climate risks in an orderly, effective and productive manner4.

With respect to the future, Frank Elderson made the following claim: “Now that European banking supervision has entered a more mature phase, we need to retain a forward-looking strategy and develop a long-term vision. Focusing on greening the financial system must be a part of this.”3.

References

1 https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2019/avoiding-the-storm-climate-change-and-the-financial-system-speech-by-sarah-breeden.pdf

2 https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/wmo-climate-statement-past-4-years-warmest-record

3 https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/press/interviews/date/2019/html/ssm.in190515~d1ab906d59.en.html

4 https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/prudential-regulation/report/transition-in-thinking-the-impact-of-climate-change-on-the-uk-banking-sector.pdf