Structural Foreign Exchange Risk in practice

Managing Capital Adequacy ratios through an open Foreign Exchange position

Since the introduction of the Pillar 1 capital charge for market risk, banks must hold capital for Foreign Exchange (FX) risk, irrespective of whether the open FX position was held on the trading or the banking book. An exception was made for Structural Foreign Exchange Positions, where supervisory authorities were free to allow banks to maintain an open FX position to protect their capital adequacy ratio in this way.

This exemption has been applied in a diverse way by supervisors and therefore, the treatment of Structural FX risk has been updated in recent regulatory publications. In this article we discuss these publications and market practice around Structural FX risk based on an analysis of the policies applied by the top 25 banks in Europe.

Based on the 1996 amendment to the Capital Accord, banks that apply for the exemption of Structural FX positions can exclude these positions from the Pillar 1 capital requirement for market risk. This exemption was introduced to allow international banks with subsidiaries in currencies different from the reporting currency to employ a strategy to hedge the capital ratio from adverse movements in the FX rate. In principle a bank can apply one of two strategies in managing its FX risk.

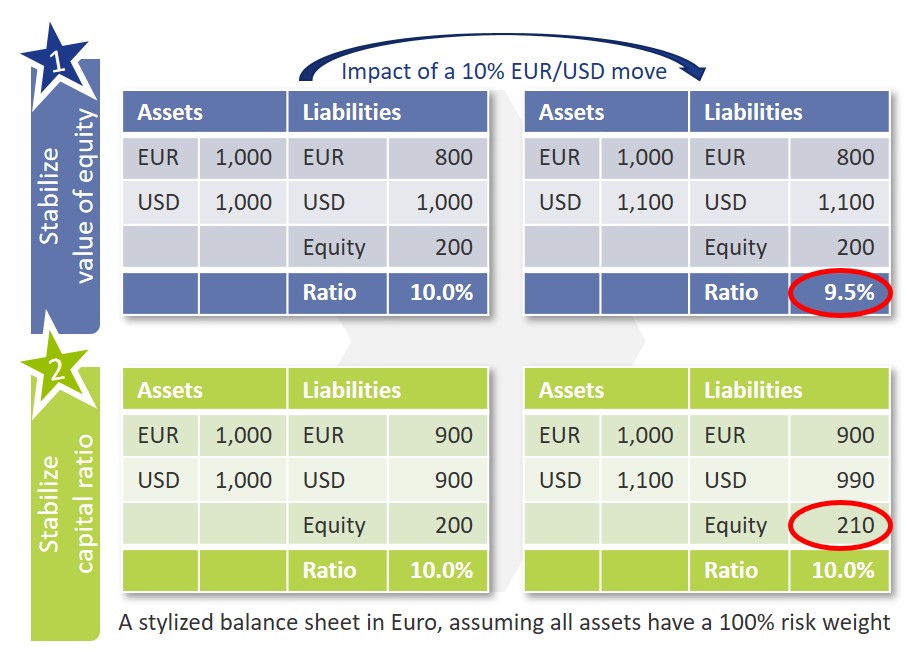

- In the first strategy, the bank aims to stabilize the value of its equity from movements in the FX rate. This strategy requires banks to maintain a matched currency position, which will effectively protect the bank from losses related to FX rate changes. Changes in the FX rate will not impact the equity of a bank with e.g. a consolidated balance sheet in Euro and a matched USD position. The value of the Risk-Weighted Assets (RWAs) is however impacted. As a result, although the overall balance sheet of the bank is protected from FX losses, changes in the EUR/USD exchange rate can have an adverse impact on the capital ratio.

- In the alternative strategy, the objective of the bank is to protect the capital adequacy ratio from changes in the FX rate. To do so, the bank deliberately maintains a long, open currency position, such that it matches the capital ratio. In this way, both the equity and the RWAs of the bank are impacted in a similar way by changes in the EUR/USD rate, thereby mitigating the impact on the capital ratio. Because an open position is maintained, FX rate changes can result in losses for the bank. Without the exemption of Structural FX positions, the bank would be required to hold a significant amount of capital for these potential losses, effectively turning this strategy irrelevant.

As can also be seen in the exhibit below, the FX scenario that has an adverse impact on the bank differs between both strategies. In strategy 1, an appreciation of the currency will result in a decrease of the capital ratio, while in the second strategy the value of the equity will increase if the currency appreciates. The scenario with an adverse impact on the bank in strategy 2 is when the foreign currency depreciates.

Until now, only limited guidance has been available on e.g. the risk management framework, (number of) currencies that can be in scope of the exemption and the maximum open exposure that can be exempted. As a result, the practical implementation of the Structural FX exemption varies significantly across banks. Recent regulatory publications aim to enhance regulatory guidance to ensure a more standardized application of the exemption.

Regulatory Changes

With the publication of the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) in January 2019, the exemption of Structural FX risk was further clarified. The conditions from the 1996 amendment were complemented to a total of seven conditions related to the policy framework required for FX risk and the maximum and type of exposure that can be in scope of the exemption. Within Europe, this exemption is covered in the Capital Requirements Regulation under article 352(2).

To process the changes introduced in the FRTB and to further strengthen the regulatory guidelines related to Structural FX, the EBA has issued a consultation paper in October 2019. A final version of these guidelines was published in July 2020. The date of application was pushed back one year compared to the consultation paper and is now set for January 2022.

The guidelines introduced by EBA can be split in three main topics:

- Definition of Structural FX.

The guidelines provide a definition of positions of a structural nature and positions that are eligible to be exempted from capital. Positions of a structural nature are investments in a subsidiary with a reporting currency different from that of the parent (also referred to as Type A), or positions that are related to the cross-border nature of the institution that are stable over time (Type B). A more elaborate justification is required for Type B positions and the final guidelines include some high-level conditions for this. - Management of Structural FX.

Banks are required to document the appetite, risk management procedures and processes in relation to Structural FX in a policy. Furthermore, the risk appetite should include specific statements on the maximum acceptable loss resulting from the open FX position, on the target sensitivity of the capital ratios and the management action that will be applied when thresholds are crossed. It is moreover clarified that the exemption can in principle only be applied to the five largest structural currency exposures of the bank. - Measurement of Structural FX.

The guidelines include requirements on the type and the size of the positions that can be in scope of the exemption. This includes specific formulas on the calculation of the maximum open position that can be in scope of the exemption and the sensitivity of the capital ratio. In addition, banks will need to report the structural open position, maximum open position, and the sensitivity of the capital ratio, to the regulator on a quarterly basis.

One of the reasons presented by the EBA to publish these additional guidelines is a growing interest in the application of the Structural FX exemption in the market.

Market Practice

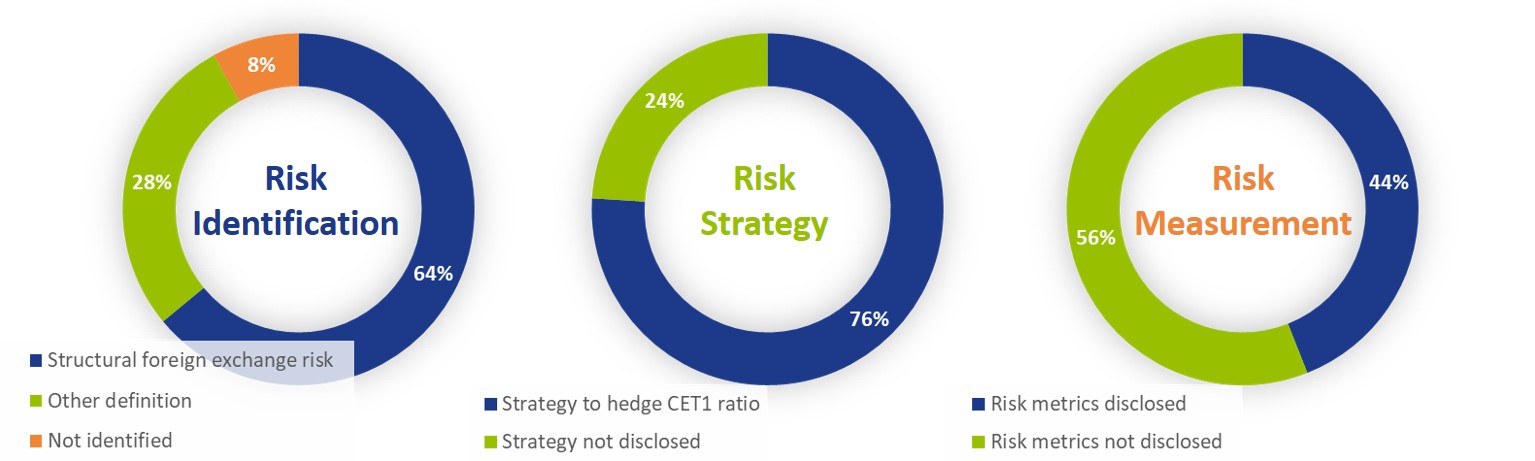

To understand the current policy applied by banks, a review of the 2019 annual reports of the top 25 European banks was conducted. Our review shows that almost all banks identify Structural FX as part of their risk identification process and over three quarters of the banks apply a strategy to hedge the CET1 ratio, for which an exemption has been approved by the ECB. While most of the banks apply the exemption for Structural FX, there is a vast difference in practices applied in measurement and disclosure. Only 44% of the banks publish quantitative information on Structural FX risk, ranging from the open currency exposure, 10-day VaR losses, stress losses or Economic Capital allocated.

The guideline that will have a significant impact on Structural FX management within the bigger banks of Europe is the limit to include only the top five open currency positions in the exemption: of the banks that disclose the currencies in scope of the Structural FX position, 60% has more than 5 and up to 20 currencies in scope. Reducing that to a maximum of five will either increase the capital requirements of those banks significantly or require banks to move back to maintaining a matched position for those currencies, which would increase the capital ratio volatility.

Conclusion

The EBA guidelines on Structural FX that will to go live by January 2022 are expected to have quite an impact on the way banks manage their Structural FX exposures. Although the Structural FX policy is well developed in most banks, the measurement and steering of these positions will require significant updates. It will also limit the number of currencies that banks can identify as Structural FX position. This will make it less favourable for international banks to maintain subsidiaries in different currencies, which will increase the cost of capital and/or the capital ratio volatility.

Finally, a topic that is still ambiguous in the guidelines is the treatment of Structural FX in a Pillar 2 or ICAAP context. Currently, 20% of the banks state to include an internal capital charge for open structural FX positions and a similar amount states to not include an internal capital charge. Including such a capital charge, however, is not obvious. Although an open FX position will present FX losses for a bank which would favour an internal capital charge, the appetite related to internal capital and to the sensitivity of the capital ratio can counteract, resulting in the need for undesirable FX hedges.

The new guidelines therefore present clarifications in many areas but will also require banks to rework a large part of their Structural FX policies in the middle of a (COVID-19) crisis period that already presents many challenges.

How to set up Intraday Bank Statement reporting in SAP

Intraday bank statement (IBS) reporting, a service that your house bank can provide your company, enables your cash manager to understand which debits and credits have cleared on your bank accounts throughout the current day. We explain how to implement it in SAP.

Intraday Bank Statements offers a cash manager additional insight in estimated closing balances of external bank accounts and therefore provides the information to manage the cash more tightly on the company’s bank accounts.

Compared to intraday bank statement reporting, end-of-day (EOD) bank statement reporting is only available the next calendar day. The information therefore always comes too late to be meaningful for cash management decisions – apart from providing an opening bank balance for the next day.

Business rationale behind IBS reporting

So, why would a Treasury typically start implementing IBS reporting in its cash management processes?

- Cash visibility: In general, IBS reporting will provide your cash management function an additional tool to improve cash visibility. Achieving cash visibility intrinsically might not be a goal of its own, but by achieving visibility, the cash manager now has information to make certain economically relevant decisions in certain situations.

- Managing cash: By creating cash visibility, we now have an opportunity to manage cash on our accounts in an intelligent way. In case we estimate a positive closing balance, we could decide to invest this surplus in, for example, a money market fund or overnight deposit to earn some return. In case of an expected deficit, we need to fund the account to ensure no EOD negative position happens. This can be achieved by transferring funds from another bank account (in same currency), swapping funds from another bank account (in different currency), or funding it from, for example, a facility drawdown.

- Reduced risk of delinquency: As we now implemented a process to increase control over our bank balances, we now have less chance of e.g. rejected payments due to insufficient available funds and therefore less chance of being delinquent on certain obligations to pay.

- Reduced requirements on overdraft facility: By reducing the chance of having insufficient funds on our account, the overdraft facility requirements can also be reduced.

- Timely clearing of open items: IBS can also be used to clear off open items throughout the day, as opposed to only rely on clearing from EOD statements. Benefit here is that KPI’s like days sales outstanding (DSO) will improve and that reconciliation effort is spread out more through time.

This article will now only focus on the cash management side; the IBS reconciliation process may be discussed another time. If you like to know more about bank reconciliation using intraday statements, feel free to reach out to us. We have a pre-developed solution that we can implement at your side.

IBS concepts

There are a few design considerations that need to be looked at before attempting to implementing this solution in SAP.

- Reporting formats: MT942, CAMT.052, BAI2 are formats that can be imported by SAP standard and are also supported by most banks to some degree. There may be some informational or structural benefits that one format has over the other which should be considered in the design.

- Reporting frequency: It is possible to agree with the bank on reporting frequencies of IBS. Ten times through working hours? Or one time only, half an hour before the payment cut-off time? In most cases, the bank will charge a fee for every statement it sends, so this should be considered in the design.

- Delta vs cumulative reporting: As it is possible for the bank to report multiple times a day, it is important to understand how the data is reported. There are two methodologies. In case of delta reporting, only new transactions are reported, relative to the previously distributed IBS. Alternatively, there is cumulative reporting, where all booked items are reported on the statement throughout the day. Delta reporting typically means that the data in your SAP system needs to be appended for every new IBS. Cumulative reporting means that every time you process an IBS in SAP, the data needs to be rebuilt completely.

- Data integration: The intraday data as provided by the bank needs to be integrated with already existing cash-relevant data to compile a proper reporting view of estimated closing balance for the day. This needs to happen in the cash management module of SAP (FF7* reports). The design of the structure of the cash management report should be carefully aligned with the liquidity structure (i.e. ZBA structure).

- Prevention of duplications: Integrating the intraday data with existing data should be designed with data duplication in mind. It is paramount that the data on the same cash movement is not counted twice from two sources and data duplication should always be prevented while designing the solution. For example, if we are not careful, a payment flow can be included in the report twice, once from the intraday statement when it is debited and once from the payment in transit GL in the SAP administration. This would result in a skewed estimated closing balance.

Ultimately, the goal here is to receive and upload intraday bank statements throughout the day and to load cash movement data into your SAP system. This cash-relevant data needs to be made visible through the cash management reports so that the cash manager can better estimate EOD balances and make intelligent decisions related to funding accounts or investing excess funds.

Setting up Intraday Bank Statement reporting in SAP

We will now go into detail on how to setup intraday statement reporting and assume that the basic FI-CO settings for e.g. the company code are already in place. We also assume that the EOD bank statement process has already been implemented. To learn how to set this up, please read this article on virtual accounts.

Cash Management

It is important to understand that intraday statement data is converted into so called ‘Memo Records’ once loaded in SAP. These memo records can be visualized in the cash management reports (FF7AN/FF7BN). We will now explain the necessary settings on the cash management report section to ensure that the intraday data can be made visible in these cash management reports.

Define planning levels

First, we need to define a planning level; a label that is assigned to all cash movements as reported on the intraday statement. The planning level is used to structure the data in the cash management reports.

The level is a two-digit label, freely definable. We set it to C1.

The sign we need to set to blank as cash movements reported on this level can be both positive and negative.

The source will be ‘BNK’. This ensures that this planning level is reported on both ‘cash position’ and ‘liquidity forecast’ in the FF7AN/FF7BN reports.

The descriptions are freely definable. We define it as ‘INTRADAY’.

Define planning types

A planning type is a label under which a ‘memo record’ is stored on the SAP database. A planning type is subsequently linked to a ‘planning level’ to ensure the underlying data can be visualized in the cash management reports.

First, we define the planning type label: we set it identical to the planning level; C1 and link it to planning level C1.

We need to define an archiving category. This defines the data retention period of the memo records. If the period is exceeded and the reorganization program is executed; the memo record data will be cleansed.

The auto-expiry option defines whether the memo record will expire automatically and becomes invisible in the cash management report output. This needs to be enabled. The idea here is that the intraday statement data will be superseded by the EOD statement data once this is loaded after midnight next calendar day. To ensure we do not double count identical cash movements from both sources, the intraday data needs to be expired.

Also, a number range and description need to be entered. No specific functional considerations are needed here.

Define grouping and maintain headers

A ‘grouping’ is a label that is used to structure the cash management report data in a meaningful manner for the user. The grouping can be selected in the cash management reports and is going to dictate how the data is shown to the user.

We will configure a grouping ‘CASHPOS’.

Maintain structure

Under the grouping we can now maintain the structure of the cash management data. For our report, we are including two components. The first component is the planning level., the second will be the GL account under which we record our bank account balances. This is the GL account we typically maintain in the house bank account data (table T012K, transaction FI13, NWBC).

For the first component we are going to add an entry as follows:

The grouping we set to ‘CASHPOS’.

The type we set to ‘E’ for planning level. Now we can define a planning level that is going to be relevant to our cash management report output.

We set the selection to C1 (our intraday planning level we defined earlier).

This setting will ensure all cash management data as stored under C1 planning level is going to be selected in the report output.

For the second component we are going to add an entry as follows:

The grouping we set to ‘CASHPOS’.

The type we set to ‘G’ for GL Account. Now we can define the bank GL account that is going to be relevant for our cash management report output.

The selection we are going to set to a GL account is saved in our bank account entry in table T012K.

This setting will ensure all cash management data as stored under the GL account and relevant for our bank account will be selected in the report output.

The combination of these two lines is going to ensure that we will only see the C1 data for our one bank account. We can add multiple lines to increase the scope of the reports output.

Importing and processing bank statements

We should now be in good shape to import our first intraday statements. We could download these statements from our electronic banking platform. Also, we could be in a situation where we already receive them through some automated H2H interface or even through SWIFT. In any case, the statements need to be imported in SAP. This can be achieved through e.g. transaction code FF.5. The most important parameters to understand here are the following:

- File parameters: Here we define the filename and storage path where our statement is saved. We also need to define what format this file is going to be; MT940, CAMT.053, or one of the many other supported formats

- Posting parameters: Here we can define whether the line items on the bank statements should be posted to general or sub-ledger. This section is not relevant for intraday statements, as SAP does not support GL postings and reconciliation from intraday statements out of the box.

- Cash management: This is the most important section, specifically for intraday statement processing. The fields and tick boxes control a few parameters:

- A/CM payment advice: This needs to be enabled to ensure that SAP creates the memo record data from the intraday statements.

- B/Summarization: This tick box controls whether a single memo record will be created for the whole delta balance as reported on the statement or for each reported debit and credit on the statement. If high volumes are expected, summarization can reduce the number of memo records and improve performance a bit. Obviously, it does reduce the data granularity.

- C/Planning type: Here we set the planning type under which the memo records are going to be recorded. In our sample we set this to C1.

- D/ Account balance: This needs to be set if we are loading intraday statements.

- Algorithms: Here we need to set the range of customer invoice reference number (XBLNR) for the electronic bank statement (EBS) algorithm, to search the payment notes for any such occurrence in a focussed manner. If we would leave these fields empty, the algorithm would not work properly and would not find any open invoice for automatic clearing. This section is not relevant for intraday statements as SAP does not support GL postings and reconciliation from intraday statements out of the box.

Once these parameters are maintained in the import variant, the system will start to load the statements and generate the required postings.

Transaction code: FF.5

Now we can check if the memo records are updated in table FDES.

Subsequently, we can check the FF7BN report for grouping ‘CASHPOS’ and observe the output.

SAP Summer College Summary

This summer, for the first time, Zanders and SAP jointly organized the SAP Summer College.

This college consisted of a three-part webinar series, in which Zanders explained best practices on important topics in the world of corporate treasury and SAP elaborated on its latest offerings to support the processes with a focus on accelerated and cloud-based deployments.

If you were not able to attend, please find the recorded webinars here. Nevertheless, we now also offer you a short, written summary of what has been discussed.

Forecasting functionalities

The topic of the first webinar was ‘Cash management & cash flow forecasting’. Pieter Sermeus, senior manager at Zanders, explained the preparations needed before you can start daily short-term cash flow forecasting and executing cash management actions. Subsequently, he explained some approaches to prepare a cash flow forecast, whereby he made the distinction in the objective (cash management, hedging or funding) and the term of the forecast (short term, mid-term or long term). Thereafter, SAP’s Christian Mnich and Christian Schmid presented their SAP Cash Management solution. This module in S/4HANA provides support in bank account management, cash positioning and short-term cash flow forecasting, and can be deployed either on premise or in the cloud. Lastly, SAP elaborated on its Analytics Cloud solution, which offers the functionality to report and slice and dice. It also offers functionality in the workflow around collecting cash flow forecasts and the slicing and dicing of the forecasted and actual items.

Payment factory capabilities

The second webinar was on ‘Payment factory optimization’. Ivo Postma, senior manager at Zanders, elaborated on the payment factory process and the relation with various departments within an organization. In addition, different payment factory models (payment forwarding, payments on behalf of and collection on behalf of), connectivity options (SWIFT, cloud provider, host-to-host and e-banking) and cash management structures (zero balance cash pools and virtual accounts) have been discussed. Subsequently, Christian Schmid presented the cloud-based service SAP Multi-Bank Connectivity as well as dedicated payment factory capabilities supported by SAP In-House Cash and SAP Advanced Payment Management.

Process optimization

The topic of the third webinar was ‘Treasury process optimization’. Jonathan Tomlinson, senior manager at Zanders, provided an overview of financial risks managed by Treasury and explained why it is so important and complex to manage FX risk. Subsequently, the Zanders risk management framework was highlighted, including risk identification, risk measurement, policy and execution process issues. As part of the execution process, the whole deal life cycle was discussed. Lastly, Christian Schmid presented SAP’s Treasury and risk management module and the possibilities with its cloud-based Trading platform integration and Hedge management cockpit. Also, SAP Treasury analytics and reporting capabilities for risk management were addressed.

We are very pleased that over 200 professionals registered to the SAP Summer College and that we received positive reactions from the attendees – thank you!

In case you have any question regarding SAP functionalities or other above-mentioned topics, please do not hesitate to contact us.

How to set up Intraday Bank Statement reporting in SAP

This summer, for the first time, Zanders and SAP jointly organized the SAP Summer College.

Intraday Bank Statements offers a cash manager additional insight in estimated closing balances of external bank accounts and therefore provides the information to manage the cash more tightly on the company’s bank accounts.

Compared to intraday bank statement reporting, end-of-day (EOD) bank statement reporting is only available the next calendar day. The information therefore always comes too late to be meaningful for cash management decisions – apart from providing an opening bank balance for the next day.

Business rationale behind IBS reporting

So, why would a Treasury typically start implementing IBS reporting in its cash management processes?

- Cash visibility: In general, IBS reporting will provide your cash management function an additional tool to improve cash visibility. Achieving cash visibility intrinsically might not be a goal of its own, but by achieving visibility, the cash manager now has information to make certain economically relevant decisions in certain situations.

- Managing cash: By creating cash visibility, we now have an opportunity to manage cash on our accounts in an intelligent way. In case we estimate a positive closing balance, we could decide to invest this surplus in, for example, a money market fund or overnight deposit to earn some return. In case of an expected deficit, we need to fund the account to ensure no EOD negative position happens. This can be achieved by transferring funds from another bank account (in same currency), swapping funds from another bank account (in different currency), or funding it from, for example, a facility drawdown.

- Reduced risk of delinquency: As we now implemented a process to increase control over our bank balances, we now have less chance of e.g. rejected payments due to insufficient available funds and therefore less chance of being delinquent on certain obligations to pay.

- Reduced requirements on overdraft facility: By reducing the chance of having insufficient funds on our account, the overdraft facility requirements can also be reduced.

- Timely clearing of open items: IBS can also be used to clear off open items throughout the day, as opposed to only rely on clearing from EOD statements. Benefit here is that KPI’s like days sales outstanding (DSO) will improve and that reconciliation effort is spread out more through time.

This article will now only focus on the cash management side; the IBS reconciliation process may be discussed another time. If you like to know more about bank reconciliation using intraday statements, feel free to reach out to us. We have a pre-developed solution that we can implement at your side.

IBS concepts

There are a few design considerations that need to be looked at before attempting to implementing this solution in SAP.

- Reporting formats: MT942, CAMT.052, BAI2 are formats that can be imported by SAP standard and are also supported by most banks to some degree. There may be some informational or structural benefits that one format has over the other which should be considered in the design.

- Reporting frequency: It is possible to agree with the bank on reporting frequencies of IBS. Ten times through working hours? Or one time only, half an hour before the payment cut-off time? In most cases, the bank will charge a fee for every statement it sends, so this should be considered in the design.

- Delta vs cumulative reporting: As it is possible for the bank to report multiple times a day, it is important to understand how the data is reported. There are two methodologies. In case of delta reporting, only new transactions are reported, relative to the previously distributed IBS. Alternatively, there is cumulative reporting, where all booked items are reported on the statement throughout the day. Delta reporting typically means that the data in your SAP system needs to be appended for every new IBS. Cumulative reporting means that every time you process an IBS in SAP, the data needs to be rebuilt completely.

- Data integration: The intraday data as provided by the bank needs to be integrated with already existing cash-relevant data to compile a proper reporting view of estimated closing balance for the day. This needs to happen in the cash management module of SAP (FF7* reports). The design of the structure of the cash management report should be carefully aligned with the liquidity structure (i.e. ZBA structure).

- Prevention of duplications: Integrating the intraday data with existing data should be designed with data duplication in mind. It is paramount that the data on the same cash movement is not counted twice from two sources and data duplication should always be prevented while designing the solution. For example, if we are not careful, a payment flow can be included in the report twice, once from the intraday statement when it is debited and once from the payment in transit GL in the SAP administration. This would result in a skewed estimated closing balance.

Ultimately, the goal here is to receive and upload intraday bank statements throughout the day and to load cash movement data into your SAP system. This cash-relevant data needs to be made visible through the cash management reports so that the cash manager can better estimate EOD balances and make intelligent decisions related to funding accounts or investing excess funds.

Setting up Intraday Bank Statement reporting in SAP

We will now go into detail on how to setup intraday statement reporting and assume that the basic FI-CO settings for e.g. the company code are already in place. We also assume that the EOD bank statement process has already been implemented. To learn how to set this up, please read this article on virtual accounts.

Cash Management

It is important to understand that intraday statement data is converted into so called ‘Memo Records’ once loaded in SAP. These memo records can be visualized in the cash management reports (FF7AN/FF7BN). We will now explain the necessary settings on the cash management report section to ensure that the intraday data can be made visible in these cash management reports.

Define planning levels

First, we need to define a planning level; a label that is assigned to all cash movements as reported on the intraday statement. The planning level is used to structure the data in the cash management reports.

The level is a two-digit label, freely definable. We set it to C1.

The sign we need to set to blank as cash movements reported on this level can be both positive and negative.

The source will be ‘BNK’. This ensures that this planning level is reported on both ‘cash position’ and ‘liquidity forecast’ in the FF7AN/FF7BN reports.

The descriptions are freely definable. We define it as ‘INTRADAY’.

Define planning types

A planning type is a label under which a ‘memo record’ is stored on the SAP database. A planning type is subsequently linked to a ‘planning level’ to ensure the underlying data can be visualized in the cash management reports.

First, we define the planning type label: we set it identical to the planning level; C1 and link it to planning level C1.

We need to define an archiving category. This defines the data retention period of the memo records. If the period is exceeded and the reorganization program is executed; the memo record data will be cleansed.

The auto-expiry option defines whether the memo record will expire automatically and becomes invisible in the cash management report output. This needs to be enabled. The idea here is that the intraday statement data will be superseded by the EOD statement data once this is loaded after midnight next calendar day. To ensure we do not double count identical cash movements from both sources, the intraday data needs to be expired.

Also, a number range and description need to be entered. No specific functional considerations are needed here.

Define grouping and maintain headers

A ‘grouping’ is a label that is used to structure the cash management report data in a meaningful manner for the user. The grouping can be selected in the cash management reports and is going to dictate how the data is shown to the user.

We will configure a grouping ‘CASHPOS’.

Maintain structure

Under the grouping we can now maintain the structure of the cash management data. For our report, we are including two components. The first component is the planning level., the second will be the GL account under which we record our bank account balances. This is the GL account we typically maintain in the house bank account data (table T012K, transaction FI13, NWBC).

For the first component we are going to add an entry as follows:

The grouping we set to ‘CASHPOS’.

The type we set to ‘E’ for planning level. Now we can define a planning level that is going to be relevant to our cash management report output.

We set the selection to C1 (our intraday planning level we defined earlier).

This setting will ensure all cash management data as stored under C1 planning level is going to be selected in the report output.

For the second component we are going to add an entry as follows:

The grouping we set to ‘CASHPOS’.

The type we set to ‘G’ for GL Account. Now we can define the bank GL account that is going to be relevant for our cash management report output.

The selection we are going to set to a GL account is saved in our bank account entry in table T012K.

This setting will ensure all cash management data as stored under the GL account and relevant for our bank account will be selected in the report output.

The combination of these two lines is going to ensure that we will only see the C1 data for our one bank account. We can add multiple lines to increase the scope of the reports output.

Importing and processing bank statements

We should now be in good shape to import our first intraday statements. We could download these statements from our electronic banking platform. Also, we could be in a situation where we already receive them through some automated H2H interface or even through SWIFT. In any case, the statements need to be imported in SAP. This can be achieved through e.g. transaction code FF.5. The most important parameters to understand here are the following:

- File parameters: Here we define the filename and storage path where our statement is saved. We also need to define what format this file is going to be; MT940, CAMT.053, or one of the many other supported formats

- Posting parameters: Here we can define whether the line items on the bank statements should be posted to general or sub-ledger. This section is not relevant for intraday statements, as SAP does not support GL postings and reconciliation from intraday statements out of the box.

- Cash management: This is the most important section, specifically for intraday statement processing. The fields and tick boxes control a few parameters:

A/CM payment advice: This needs to be enabled to ensure that SAP creates the memo record data from the intraday statements.

B/Summarization: This tick box controls whether a single memo record will be created for the whole delta balance as reported on the statement or for each reported debit and credit on the statement. If high volumes are expected, summarization can reduce the number of memo records and improve performance a bit. Obviously, it does reduce the data granularity.

C/Planning type: Here we set the planning type under which the memo records are going to be recorded. In our sample we set this to C1.

D/ Account balance: This needs to be set if we are loading intraday statements. - Algorithms: Here we need to set the range of customer invoice reference number (XBLNR) for the electronic bank statement (EBS) algorithm, to search the payment notes for any such occurrence in a focussed manner. If we would leave these fields empty, the algorithm would not work properly and would not find any open invoice for automatic clearing. This section is not relevant for intraday statements as SAP does not support GL postings and reconciliation from intraday statements out of the box.

Once these parameters are maintained in the import variant, the system will start to load the statements and generate the required postings.

Transaction code: FF.5

Now we can check if the memo records are updated in table FDES.

Subsequently, we can check the FF7BN report for grouping ‘CASHPOS’ and observe the output.

An SAP cockpit for seamless transfer pricing compliance

This summer, for the first time, Zanders and SAP jointly organized the SAP Summer College.

Therefore, we decided to leverage our cloud-based solution and enable SAP users to determine the arm’s length interest rate with just a few clicks.

The pricing of various treasury transactions, as for all intercompany flows, is subject to transfer pricing regulation. In essence, treasury and tax professionals need to ensure that the pricing is in line with market conditions, i.e. the arm’s length principle. To this end, numerous Zanders clients use the Zanders Inside Transfer Pricing Solution (TPS). Our TPS enables them to set interest rates on intercompany transactions in a compliant and automated way. Since its go-live almost three years ago, clients have priced over 1000 intercompany loans with this self-service solution.

Our TPS has been a stand-alone tool on the Zanders Inside platform, but that is about to change. We have selected SAP as the first treasury management system for online integration. The interface uses APIs between the two systems to pull and push the relevant information. This article will elaborate on how the process flow is designed from an end user perspective.

Automated credit rating assessment

Initially, the necessary static data on the borrowing entities needs to be saved on the Zanders Inside platform. This data is used to determine an entity-specific credit rating, a requirement for a compliant transfer pricing assessment. This can be done via the Zanders Inside template, which gives the user a standard framework to capture the financial statements for all entities. Additionally, the user also saves qualitative rating information. Based on this information, the automated credit rating assessment is run in the background. The borrower credit rating will be used as input to the pricing assessment. This first step is the only manual process in the entire end-to-end flow. In addition, adjustments to the static data only need to occur once per year, i.e. when the new financial statements are published.

Overview

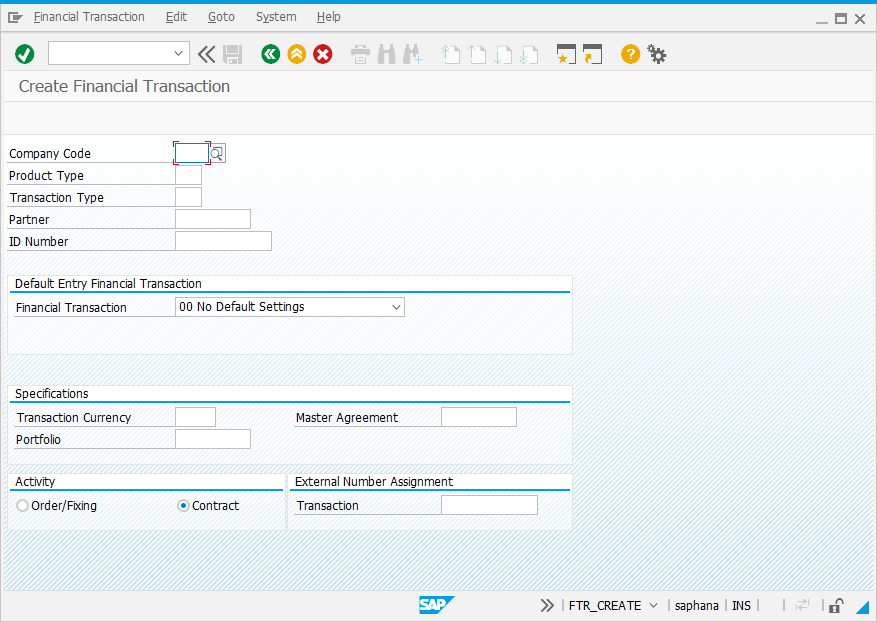

Once the static data is set up, the user enters an intercompany loan in the usual way. In the interest condition, the SAP user will indicate that the interest rate will be determined using the Zanders TPS platform. Using the SAP standard functionality, the user can define if the interest rate has to be updated via the Zanders TPS platform regularly or only initially at deal creation. Once the deal is created, the Zanders TPS cockpit offers an overview of all intercompany loans with outstanding pricing status. From this environment, the user can select the individual deals and raise a pricing request to the Zanders TPS platform. This pricing request will include identification of the lender and borrower, which impacts the rating, and the relevant terms and conditions of the loan, which impact the arm’s length interest rate.

Transferred values

Aside from the rating, the main drivers are the maturity of the loan, the structure of the facility (level of collateral), the currency and the repayment schedule. These values will be transferred into the Zanders Inside TPS. It enables the solution to operate as a calculation engine, i.e. making the necessary calculations in the background.

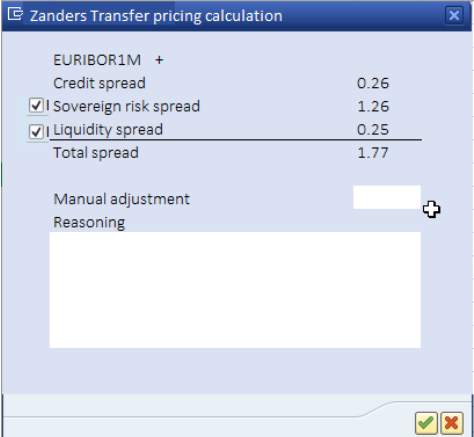

In the Zanders TPS cockpit, the user is offered the possibility to review the received interest rate and its constituting components. Given the background of the transaction, the user is free to decide which components will be included in the final rate. Additionally, a manual rate adjustment can be added as a separate component, together with an explanatory comment. The manual rate adjustment and its justification is transferred back to the Zanders TPS platform and will be included in the final pricing documentation.

Fully-fledged report

Finally, the output of the transfer pricing solution is twofold. In addition to pulling the interest rate components into SAP, it will automatically create a fully-fledged transfer pricing report. This report will automatically be saved in the solution and includes a reference towards the transaction identifier in SAP. The report contains the methodology as well as all specifics of the calculation and can be used as a reference document later on. This can be used should a tax audit occur, for example.

Determining the interest rate and entering it into the appropriate deal in a TMS system is often a manual and cumbersome process involving different departments. By connecting the Zanders Inside TPS to SAP, the level of straight-through processing (STP) within a treasury department can significantly improve. Additionally, it offers a less error-prone alternative as it removes manual data entry and calculations.

Free Demo

Would you like to learn more on this new initiative or receive a free demo of our solution? Do not hesitate to reach out!

Can you automate SAP for free?

Managing Capital Adequacy ratios through an open Foreign Exchange position

Even though ERP systems automate most of the handling of accounting and financial activities, many of us still have the drive to seek even further for automation. Even the shortest routines that need to be carried out daily can become irritating and become source of avoidable errors. Wouldn’t it be nice to limit repetitive clicking and typing to the minimum and have more time to focus on what really matters? When looking into automating activities in SAP, the first idea might be to simply ’write a program’ to take care of executing the task at hand. But how can you automate SAP safely, successfully and for free?

The language used to write most programs in SAP is called ABAP (Advanced Business Application Programming). This is an extremely powerful tool. ABAP programs sit directly on the foundation of the SAP system and can be used to change the behavior of existing programs (for example the T-Codes you use every day to perform your tasks), as well as write complete new functionality. Unfortunately, ABAP is so powerful that it cannot be used to automate activities for free, because any development in ABAP must be strictly controlled. It needs to be written by an experienced ABAP developer and needs to go through a strict set of testing cycles before being used in production. Not only do you need to make sure that the new code works as expected, you also (even more importantly) need to make sure that ’nothing else gets broken’ by the new code. You will need to employ experienced programmers and testers and you will have to deal with the expensive overhead that comes with making everyone at IT comfortable with your shiny new automation.

A development in ABAP is therefore going to require, even for an experienced programmer, an investment in both time and money.

But what if you just wanted to automate the clicking and the typing that a user performs on screen without adding any logic inside the SAP system?

In this case, Robotic Process Automation (RPA) comes to mind. RPA is a software that allows virtual ’Robots’ to interact with any application available on screen, much like a human does. RPA, unlike ABAP, can only interact with the GUI (Graphical User Interface – i.e. the SAP screen) so there is no risk of causing damage to your SAP system – at least, no more damage than a human end user could cause.

Figure 1: Example of a SAP GUI screen

RPA is perfect if you need to interact with multiple applications and it usually also comes packaged with a handy infrastructure that can take care of audit trails, monitoring dashboards, version control systems, logging systems, centralized credential management, licensing management and much more.

While this sounds very promising, in most cases you cannot automate SAP for free using RPA. Vendors of RPA provide free trials or even free-for-private-use ’community editions’, but in most cases you will still need to buy licenses to use RPA in production.

But what if you just wanted to automate the clicking and the typing that a user performs on screen, if you did not need to add any logic inside the SAP system? If you only wanted to interact with a handful of applications – let’s say SAP and Excel – and you were not interested in all the fancy extra features that come packaged with RPA?

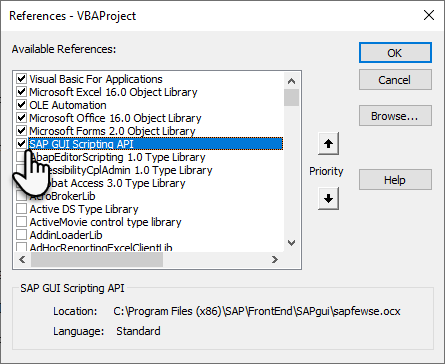

In this case, you can use another tool called SAP GUI Scripting API. Just like with RPA, you can use the SAP GUI Scripting API to emulate the activities that the user would perform on the SAP GUI screen. You can even record the activities the user performs and use the automatically generated code as a starting point for your automation.

You can write scripts in your favorite language, but since Excel <-> SAP interaction is popular, you often see SAP GUI Scripting API being used in a VBA Macro in Excel. All you need to do is add the reference to the API in your VBA editor and you can then start programming which buttons you want to click, what you want to type or what you want to read from the SAP GUI.

Figure 2: Adding the reference to SAP Scripting API in the BVA Editor

And now the recurring question: can you automate SAP for free using SAP GUI Scripting API? Yes! If you have SAP GUI installed on your machine, you should already have access to the Scripting API. You do not need to purchase additional licenses (or wait for the long procurement process to take place).

Okay, SAP GUI Scripting API is free. But is it safe?

Yes, absolutely. Quoting the official SAP GUI Scripting Security Guide: “From the SAP server’s point of view there is no difference between SAP GUI communication generated by a script and SAP GUI communication generated by a user. For this reason, a script has the same rights to run SAP transactions and enter data as the user starting it. In addition, the same data verification rules are applied to data entered by a user and data entered by a script.”

In other words:

- A script cannot corrupt the SAP system’s data, because all changes done from a script are subject to the same data validation rules as end user interaction.

- An end user cannot use a script to access data they would not otherwise have the necessary privileges for. The script only has access to the data that the end user has the access rights for.

- A script cannot record passwords. A script cannot be played back if the user running it does not have an account on the SAP system.

- A script cannot be run in the background without the end user’s knowledge. By default, the end user will be notified when the scripting starts. Furthermore, the SAP GUI needs to be displayed when the script is running.

So, SAP GUI Scripting API is free and it is safe. But is it useful?

Yes, it is. We have used this technology extensively and we have saved ourselves and our clients thousands of hours of repetitive work. Recently, a custom Process Automation tool Zanders developed for British American Tobacco was chosen by the jury of treasurytoday magazine as the winner of the Best Fintech Solution – Adam Smith Award. This award-winning tool was built by leveraging the power of SAP GUI Scripting API.

The key advantage with the SAP GUI Scripting API is that you can use a native SAP functionality designed to allow end users (and not only experienced developers) to automate activities safely and effectively. The IT and procurement overhead is kept to the minimum, allowing you to efficiently avoid those repetitive clicking and typing kind of tasks (and the errors they cause) and to instead focus on what really matters.

Are you interested in knowing more on how you can use ABAP, RPA or SAP Scripting API to automate activities in SAP? Please contact Philip Costa Hibberd for more information.

Virtual Account Concepts

This summer, for the first time, Zanders and SAP jointly organized the SAP Summer College.

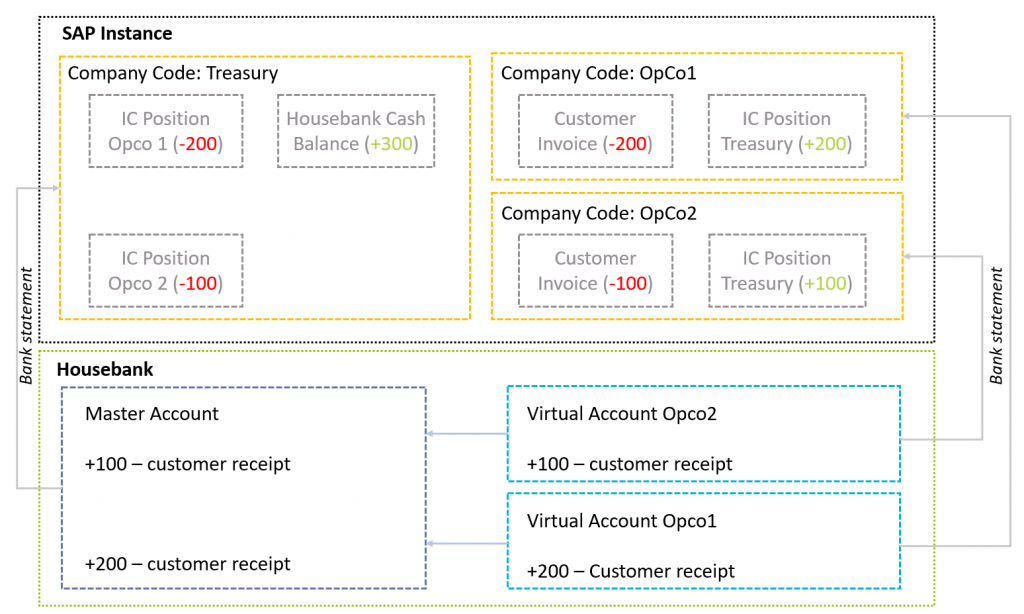

There are many concepts in which a virtual account can be deployed. In this second article on ‘How to setup virtual accounts in SAP’, we depict the concept that can be implemented in SAP the easiest without needing specialized modules like SAP Inhouse cash; all can be supported in the SAP FI-CO module.

In the process, we rely on a simple set of building blocks:

- GL accounts to manage positions between the OpCo’s and Treasury and GL accounts to manage the external cash balance.

- Receipt and processing of external bank statements.

- On the external bank statement for the Master Account, an identifier needs to be available that conveys to which virtual account the actual collection was originally credited. This identifier ultimately tells us to which OpCo these funds originally belongs to.

How to implement virtual accounts in SAP

This part assumes that the basic FI-CO settings for i.e. the company code and such are already in place.

Master Data – General Ledger Accounts

Two sets of GL accounts need to be created: balance sheet accounts for the representation of the intercompany positions and the GL account to represent the cash position with the external bank.

These GL accounts need to be assigned to the appropriate company codes and can now be used to in the bank statement import process.

Transaction code FS00

House bank maintenance bank account maintenance

In order to be able to process bank statements and generate GL postings in your SAP system, we need to maintain the house bank data first. A house bank entry comprises of the following information that needs to be maintained carefully:

- The house bank identifier: a 5-digit label that clearly identifies the bank branch

- Bank country: The ISO country code where the bank branch is located.

- Bank key: The bank key is a separate bank identifier that contains information like SWIFT BIC, local routing code and address related data of your house bank

Transaction code FI12

Secondly, under the house bank entry, the bank accounts can be created.

- The account identifier: a 5-digit label that clearly identifies the bank account

- Bank account number and IBAN: This represents the bank account number as assigned to you by the bank.

- Currency: the currency of the bank account

- G/L Account: the general ledger account that is going to be used to represent the balance sheet position on this bank account.

Transaction code FI12 in SAP ECC or NWBC in S/4 HANA

The idea here is that we maintain one house bank and bank account in the treasury company code that represents the Master account as held with your house bank. This house bank will have the G/L account assigned to it that represents the house banks external cash position.

In each of the OpCo’s company codes, we maintain one house bank and bank account that represents each of the “virtual” bank accounts as held with your house bank. This house bank will have the G/L account assigned to it that represents the intercompany position with the treasury entity.

Electronic Bank Statement settings

The Electronic Bank Statement (EBS) settings will ensure that, based on the information present on the bank statement, SAP is capable of posting the items into the general or sub ledgers according to the requirements. There are a few steps in the configuration process that are important for this to work:

- Posting rule construction

Posting rules construction starts with setting up Account symbols and assigning GL accounts to it. The idea here is to define at least three account symbols to represent the external Cash position (BANK), the IC position with OpCo1 (OPCO1) and thirdly the IC position with OpCo2 (OPCO2). A separate account symbol for customers is not required in SAP.

For the account symbol for BANK we do not assign a GL account number directly in the settings; instead we will assign a so-called mask by entering the value “+++++++++”. What this does in SAP is for every time the posting rule attempts to post to “BANK”, the GL account as assigned in the house bank account settings is used (FI12 or NWBC setting above).

For the account symbol OPCO1 and OPCO2 we can assign a dedicated balance sheet GL that represents the IC position with those OpCo’s. These GL accounts have already been created in the first step (FS00).

Now we have the account symbols prepared, we can start tying together these symbols into posting rules. We need to create 3 posting rules.

Posting rule 1 is going to debit the BANK symbol and it is going to credit OPCO1 symbol.

Posting rule 2 is going to debit the BANK symbol and it is going to credit OPCO2 symbol.

Posting rule 3 is going to debit the BANK symbol and it is going to credit a BLANK symbol. The posting type however is going the be set to value 8 “Clear Credit Subledger Account”. What this setting is going to attempt is that it will try to clear out any open item sitting in the customer sub-ledger using “Algorithms”. More on algorithms a bit later.

As you can imagine, posting rules 1 and 2 are applicable for the treasury entity. Posting rule 3 is going to be used in the OpCo’s EBS process.

Transaction code OT83 - Posting rule assignment

In the next step we can assign the posting rules to the so-called “Bank Transaction Codes” (or BTC’s like i.e NTRF) that are typically observed in the body of the bank statements to identify the nature of the transactions.

To understand under which Bank Transaction Code these collections are reported on the statement, you typically need to carefully analyze some sample statement output or check with your banks implementation team for feedback.

Important to note here is to assign an algorithm to posting rule 3. This algorithm will attempt to search the payment notes of the bank statement for “Reference Numbers” which it can use to trace back the original customer invoice open item. Once SAP has identified the correct outstanding invoice, it can actually clear this one off and identify it as being paid.

Transaction code OT83 - Bank account assignment

In the last part we can then assign the posting rules assignments to the bank accounts. This way we can differentiate different rule assignments for different accounts if that is needed.

Transaction code OT83 - Search Strings

If the posting rule assignment needs more granularity than the level provided in step 2 above here (on BTC level), we can setup search strings. Search strings can be configured to look at the payment notes section of the bank statement and find certain fixed text or patterns of text. Based on such search strings we can then modify the posting behavior by for instance overruling the posting rule assignment as defined in step 2.

Whether this is required depends on the level of information that is provided by the bank in the bank statements.

Transaction code OTPM

Importing and processing bank statements

We should now be in good shape to import our first statements. We could download them from our electronic banking platform. We could also be in a situation where we already receive them through some automated H2H interface or even through SWIFT. In any case, the statements need to be imported in SAP. This can be achieved through transaction code FF.5. The most important parameters to understand here are the following:

- File parameters: Here we define the filename and storage path where our statement is saved. We also need to define what format this file is going to be, i.e. MT940, CAMT.053 or one of the many other supported formats

- Posting Parameters: Here we can define if the line items on the bank statements are going to be posted to general or sub-ledger.

- Algorithms: Here we need to set the range of customer invoice reference number (XBLNR) for the EBS Algorithm to search the payment notes for any such occurrence in a focused manner. If we would leave these fields empty, the algorithm will not work properly and will not find any open invoice for automatic clearing.

Once these parameters are maintained in the import variant, the system will start to load the statements and generate the required postings.

Transaction code FF.5

Closing remarks

Other concepts could be where a payment factory is already implemented using i.e. SAP IHC and the customers wants to seek additional benefits by using the virtual account functionality of its bank.

This is the second part of a series on how to set up virtual accounts in SAP. Click here to read the first part. A next part, including more complex concepts, will be published soon.

For questions please contact Ivo Postma.

A streamlined way to deliver your digital treasury strategy

This summer, for the first time, Zanders and SAP jointly organized the SAP Summer College.

The importance and benefits of delivering a digital strategy for treasury operations are well understood. For many organizations, however, there is a significant barrier that may prevent them from being able to successfully implement. In this article, we discuss how to overcome that barrier, resulting in an accelerated process to achieve a true smart treasury function at lower overall cost.

As discussed in the recent joint-whitepaper from Zanders and Citi on the future of corporate treasury, both corporations and financial institutions should be focusing their attention on developing a digital treasury strategy. This is being driven by the increasing pace of regulatory change, continuously evolving business models, volatile economic conditions, fast-growing technological developments and the benefits of a strategically focused ‘smart treasury’ – one that utilizes the latest technology to be more integrated, automated and optimized, adding value to the business.

Although the benefits of going digital are well recognized at a company level, they are not at the treasury level – while two-thirds of respondents to a digital preparedness survey indicated their organizations are already engaged and experimenting with digital solutions, only 14% had a digital strategy in treasury.

Strategy void

We know the levels of adoption of a digital treasury strategy vary greatly between organizations – at the top end of the scale, a number of trailblazers have already developed theirs and are actively implementing, firmly on their way to achieving the smart treasury vision. These are normally financial institutions and large multinationals who utilize in-house technology teams containing a pool of resources dedicated to treasury technology and digital transformation. They may also have ample means to utilize external advisors to deliver on their behalf.

A void exists, however, comprised either of corporates that are yet to transform from traditional MS Excel-based methods to an ‘efficient treasury’ function, or those that have already traversed the transformation pathway but are unable to progress further to ‘smart’.

For those yet to progress to an ‘efficient’ function and realize the benefits of centralization, standardization and automation, getting the basics right is the first hurdle to overcome before digital transformation can be considered. To do this, they should look to select and implement a treasury management system (TMS) and, where appropriate, run a fully operational in-house bank and payment factory. However, in this scenario, the size and scale of their business makes it unlikely that in-house teams with the requisite knowledge and skills to do this exist, and the cost of external advisory projects can be prohibitive. Their barrier is one of having the right structure and resources in place.

For those that have already traversed the treasury transformation pathway and are experiencing the benefits of their new ‘efficient treasury’ function, such as improved cash management, reduced transaction costs, standardized processes and increasingly effective risk management, ‘smart treasury’ is the natural next step. But they also face similar significant barriers in developing and implementing their digital treasury strategy to those struggling to progress to ‘efficient’ – the lack of in-house teams and no budget for advisory projects. Once again, the issue of structure and resources is the barrier.

Progressing through efficient to smart

In our discussion of the aforementioned joint-whitepaper, Ron Chakravarti, Citi’s Global Head of Treasury Advisory, commented: “Today, more than ever, the treasury function needs to include people who are technologically savvy. People who are able to comprehend what is changing and how to best deploy technology… Treasury teams recognize that they need to have a digital strategy, but many of them are not fully equipped to define one.”

Looking more closely at the current team structure of corporates that struggle to achieve their efficient or smart aspirations, it is clear they either have difficulty in finding technologically savvy people, or this requirement is simply being overlooked. The ways that organizations try to respond to the resourcing challenge varies. Some choose to divide the role among existing team members, others merge the requirements into an existing role, and in some cases a dedicated treasury systems manager role is created.

However, none of these solutions are optimal, as to effectively deliver digital change the following niche set of ‘digital treasury’ skills are required:

- Intricate knowledge of the business coupled with detailed working and technical knowledge of their treasury operations and a strong understanding of corporate treasury principles in general.

- Well versed in the latest technologies on offer, and any future technology in the pipeline, that could be effectively utilized by the organization based on their current and future needs.

- Practical experience of implementing and integrating a variety of new digital technologies, combined with strong general IT skills and awareness.

Finding the right resource in a niche market is a challenging one and finding a solution to overcome this becomes critical to moving forwards. We propose a way to remove this barrier and deliver a digital treasury strategy in a lean and cost-effective way, while opening the door to a multitude of further opportunities and benefits for your new ‘smart treasury’ function.

An alternative way to manage your treasury systems

The creation of a dedicated treasury systems manager role appears to be the best of the current solutions to the resourcing barrier, but in practice this is a difficult role to fill due to a trade-off between cost and experience. How can organizations find a senior resource not only with strong experience and understanding of treasury, but with excellent knowledge of the latest treasury technology trends, experience implementing them, and a network of other financial technology professionals on call to resolve issues and propose new ways of working?

One solution may be to form a treasury technology partnership with a third-party, who will assume all day-to-day treasury systems management tasks while defining and delivering the digital treasury strategy. This suggestion is not the costly advisory solution previously mentioned that can be prohibitive for corporates struggling to transform. Contrary to expectations, there are savings to be made and other significant benefits to be enjoyed when a treasury technology partnership is compared to employing a dedicated treasury systems manager.

Treasury technology partnership benefits

Cost reduction – your partner will be able to perform the day-to-day treasury systems management service at lower cost than an in-house treasury systems manager. This is because it can be delivered by a pool of dedicated systems admin staff, allowing the benefits from economies of scale to be realized. The quality of service would also improve based on the collective knowledge of the partner, who will also be managing the same systems for other clients.

Accelerated strategy – your partner will be uniquely placed to define and deliver your digital strategy quicker than can be achieved by the treasury team or a stand-alone systems manager. They would be able to achieve this by applying extensive company-specific knowledge gained during the partnership, along with their awareness and experience of the latest technology. They will already have solutions for common treasury issues and will be supported by their in-house team of treasury technology professionals.

Additionally, the accelerated strategy could be delivered at a lower cost than any discrete transformation advisory project, as the technology partner would benefit from already having a strong understanding of your business’s strategic and technical requirements. Time spent on scoping would be vastly reduced.

Ad-hoc – for similar reasons to the accelerated strategy, the treasury technology partner would also be able to deliver ad-hoc projects at a much more reasonable cost than engaging in an advisory project. Tasks such as systems selections, technical changes required by regulatory changes, market reform or adjustments in generally accepted best practice, could be delivered swiftly as the technology partner would already be experienced in delivering these for other customers, while also being aware of your specific technical requirements.

Exponential technology – the use of a treasury technology partner will open up the possibility of always being able to deploy the latest technology. For example, Zanders are already experienced in delivering technological improvements utilizing robotic process automation (RPA), machine learning (ML), artificial intelligence (AI), external and internal APIs, custom applications/middleware, and a multitude of other exponential technologies. The technology partner will already be experienced in the design, implementation and use of these with their other clients, and will bring significant experience in how to deliver these, in conjunction with their understanding of your organization’s strategic and technical requirements.

Summary

Zanders has a wealth of experience in this field with numerous awards and recognitions for our technological solutions, and already performs similar services for several organizations. Entering into a Zanders Treasury Technology Partnership to deliver your first steps to an efficient treasury, perform day-to-day systems admin tasks, and develop and implement the digital treasury strategy, is an ideal solution for those corporates lacking the appropriate resources to move from ‘efficient’ to ‘smart’.

Moreover, it gives an organization access to a pool of treasury professionals at all levels of seniority, to continuously benefit from their collective experience and skills. This expertise is available at a lower cost than the alternative of employing an in-house treasury systems manager or engaging in advisory projects. For cases where the current systems admin tasks are merged into one or several existing roles, it will allow core treasury team members to focus on treasury management by removing the burden of systems management placed upon them, while also improving the quality of the systems management service.

Finally, it opens up the possibility of greater use of a multitude of exponential technologies, all resulting in cost savings, increased operational efficiencies, improved risk management, and a technology landscape that is scalable and rapidly deployable. This will ensure you achieve your smart treasury vision for a function that is well placed to support your business going forward.

Calculation of compounded SARON

Managing Capital Adequacy ratios through an open Foreign Exchange position

In our previous article, the reasons for a new reference rate (SARON) as an alternative to CHF LIBOR were explained and the differences between the two were assessed. One of the challenges in the transition to SARON, relates to the compounding technique that can be used in banking products and other financial instruments. In this article the challenges of compounding techniques will be assessed.

Alternatives for a calculating compounded SARON

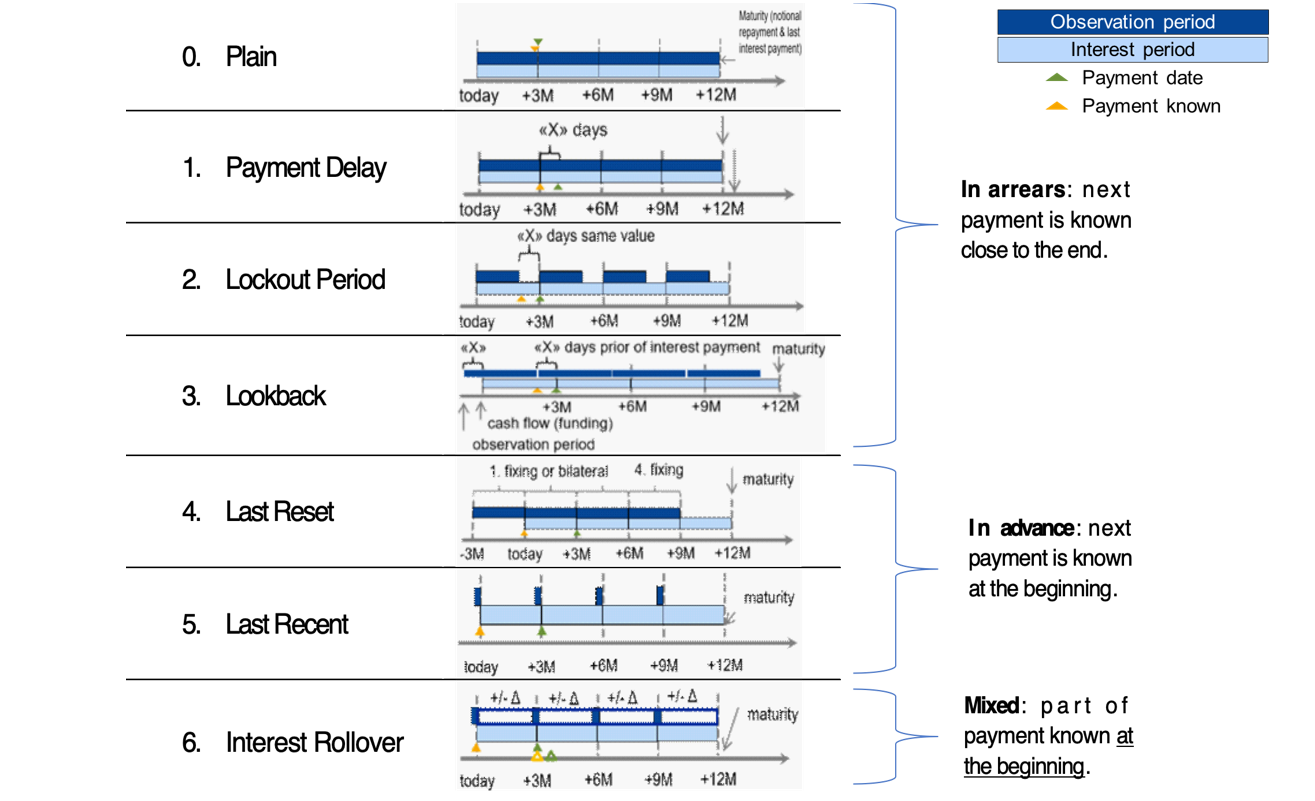

After explaining in the previous article the use of compounded SARON as a term alternative to CHF LIBOR, the Swiss National Working Group (NWG) published several options as to how a compounded SARON could be used as a benchmark in banking products, such as loans or mortgages, and financial instruments (e.g. capital market instruments). Underlying these options is the question of how to best mitigate uncertainty about future cash flows, a factor that is inherent in the compounding approach. In general, it is possible to separate the type of certainty regarding future interest payments in three categories . The market participant has:

- an aversion to variable future interest payments (i.e. payments ex-ante unknown). Buying fixed-rate products is best, where future cash flows are known for all periods from inception. No benchmark is required due to cash flow certainty over the lifetime of the product.

- a preference for floating-rate products, where the next cash flow must be known at the beginning of each period. The option ‘in advance’ is applicable, where cash flow certainty exists for a single period.

- a preference for floating-rate products with interest rate payments only close to the end of the period are tolerated. The option ‘in arrears’ is suitable, where cash flow certainty only close to the end of each period exists.

Based on the Financial Stability Board (FSB) user’s guide, the Swiss NWG recommends considering six different options to calculate a compounded risk-free rate (RFR). Each financial institution should assess these options and is recommended to define an action plan with respect to its product strategy. The compounding options can be segregated into options where the future interest rate payments can be categorized as in arrears, in advance or hybrid. The difference in interest rate payments between ‘in arrears’ and ‘in advance’ conventions will mainly depend on the steepness of the yield curve. The naming of the compounding options can be slightly different among countries, but the technique behind those is generally the same. For more information regarding the available options, see Figure 1.

Moreover, for each compounding technique, an example calculation of the 1-month compounded SARON is provided. In this example, the start date is set to 1 February 2019 (shown as today in Figure 1) and the payment date is 1 March 2019. Appendix I provides details on the example calculations.

Figure 1: Overview of alternative techniques for calculating compounded SARON. Source: Financial Stability Board (2019).

0) Plain (in arrears): The observation period is identical to the interest period. The notional is paid at the start of the period and repaid on the last day of the contract period together with the last interest payment. Moreover, a Plain (in arrears) structure reflects the movement in interest rates over the full interest period and the payment is made on the day that it would naturally be due. On the other hand, given publication timing for most RFRs (T+1), the requiring payment is on the same day (T+1) that the final payment amount is known (T+1). An exception is SARON, as SARON is published one business day (T+0) before the overnight loan is repaid (T+1).

Example: the 1-month compounded SARON based on the Plain technique is like the example explained in the previous article, but has a different start date (1 February 2019). The resulting 1-month compounded SARON is equal to -0.7340% and it is known one day before the payment date (i.e. known on 28 February 2019).

1) Payment Delay (in arrears): Interest rate payments are delayed by X days after the end of an interest period. The idea is to provide more time for operational cash flow management. If X is set to 2 days, the cash flow of the loan matches the cash flow of most OIS swaps. This allows perfect hedging of the loan. On the other hand, the payment in the last period is due after the payback of the notional, which leads to a mismatch of cash flows and a potential increase in credit risk.

Example: the 1-month compounded SARON is equal to -0.7340% and like the one calculated using the Plain (in arrears) technique. The only difference is that the payment date shifts by X days, from 1 March 2019 to e.g. 4 March 2019. In this case X is equal to 3 days.

2) Lockout Period (in arrears): The RFR is no longer updated, i.e. frozen, for X days prior to the end of an interest rate period (lockout period). During this period, the RFR on the day prior to the start of the lockout is applied for the remaining days of the interest period. This technique is used for SOFR-based Floating Rate Notes (FRNs), where a lockout period of 2-5 days is mostly used in SOFR FRNs. Nevertheless, the calculation of the interest rate might be considered less transparent for clients and more complex for product providers to be implemented. It also results in interest rate risk that is difficult to hedge due to potential changes in the RFR during the lockout period. The longer the lockout period, the more difficult interest rate risk can be hedged during the lockout period.

Example: the 1-month compounded SARON with a lockout period equal to 3 days (i.e. X equals 3 days) is equal to -0.7337% and known 3 days in advance of the payment date.

3) Lookback (in arrears): The observation period for the interest rate calculation starts and ends X days prior to the interest period. Therefore, the interest payments can be calculated prior to the end of the interest period. This technique is predominately used for SONIA-based FRNs with a delay period of X equal to 5 days. An increase in interest rate risk due to changes in yield curve is observed over the lifetime of the product. This is expected to make it more difficult to hedge interest rate risk.

Example: assuming X is equal to 3 days, the 1-month compounded SARON would start in advance, on January 29, 2019 (i.e. today minus 3 days). This technique results in a compounded 1-month SARON equal to -0.7335%, known on 25 February 2019 and payable on 1 March 2019.

4) Last Reset (in advance): Interest payments are based on compounded RFR of the previous period. It is possible to ensure that the present value is equivalent to the Plain (in arrears) case, thanks to a constant mark-up added to the compounded RFR. The mark-up compensates the effects of the period shift over the full life of the product and can be priced by the OIS curve. In case of a decreasing yield curve, the mark-up would be negative. With this technique, the product is more complex, but the interest payments are known at the start of the interest period, as a LIBOR-based product. For this reason, the mark-up can be perceived as the price that a borrower is willing to pay due to the preference to know the next payment in advance.

Example: the interest rate payment on 1 March 2019 is already known at the start date and equal to -0.7328% (without mark-up).

5) Last Recent (in advance): A single RFR or a compounded RFR for a short number of days (e.g. 5 days) is applied for the entire interest period. Given the short observation period, the interest payment is already known in advance at the start of each interest period and due on the last day of that period. As a consequence, the volatility of a single RFR is higher than a compounded RFR. Therefore, interest rate risk cannot be properly hedged with currently existing derivatives instruments.

Example: a 5-day average is used to calculate the compounded SARON in advance. On the start date, the compounded SARON is equal to -0.7339% (known in advance) that will be paid on 1 March 2020.

6) Interest Rollover (hybrid): This technique combines a first payment (installment payment) known at the beginning of the interest rate period with an adjustment payment known at the end of the period. Like Last Recent (in advance), a single RFR or a compounded RFR for a short number of days is fixed for the whole interest period (installment payment known at the beginning). At the end of the period, an adjustment payment is calculated from the differential between the installment payment and the compounded RFR realized during the interest period. This adjustment payment is paid (by either party) at the end of the interest period (or a few days later) or rolled over into the payment for the next interest period. In short, part of the interest payment is known already at the start of the period. Early termination of contracts becomes more complex and a compensation mechanism is needed.