We are very delighted that our client Sony Group Corporation has been awarded winner of an Adam Smith Award in the category of ‘Best Treasury Transformation project’.

The winners’ announcements of the 2022 Adam Smith Awards took place on 12 May in London. On that date Hiroyuki Ishiguro, Gurmeet Jhita and Terry Vouvoudakis, on behalf of their teams, were announced as the winners of this prestigious award.

On 14 June, during the Awards dinner, the award was physically presented to Hiroyuki Ishiguro and Gurmeet Jhita, who were leading Sony’s global treasury transformation project, which started in 2018. Judith van Paassen received the award on behalf of Zanders. Zanders was one of the eight partners named during the announcement, together with SAP, MUFG, SMBC, J.P. Morgan, Citi, HSBC and 360T.

The Adam Smith Awards are now in their 15th year and are recognized across the world as the ultimate benchmark of corporate achievement and exceptional solutions in treasury. The standard of submissions this year was of the very highest level, with 230 nominations spanning 34 countries. A list of all Adam Smith award winners can be found here on the Treasury Today website.

Over the course of the 2022 Adam Smith Awards season, Treasury Today will host a dedicated podcast series, case study series and social media celebration of this year’s winning projects.

Foto: Adam Smith Award winners for Best Treasury Transformation Project. From left to right: Vitantonio Musa, Lee Titchmarsh, Gurmeet Jhita, Laura Koekkoek, Hiroyuki Ishiguro, Judith van Paassen, Beliz Ayhan, Fred Pretorius

With SAP recently focusing heavily on developing its S/4HANA Cloud solutions, now is an opportune time for corporate executives to investigate the deployment options and weigh up the investment versus the benefit of each.

Changing IT infrastructure and systems is costly, and executives need the right knowledge to make informed decisions to best meet their current and future demands at the optimal price point. What are the best options?

We will start by looking at the features of the various options before taking a deeper dive into what the differences are specifically for Treasury Management on SAP S/4HANA and how that might influence decisions.

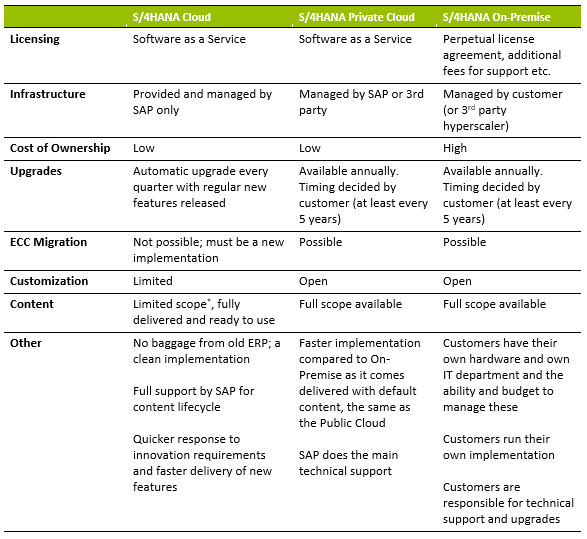

The main features are summarized in the table below:

*Scope covered should be sufficient for small to medium corporate treasuries, depending on complexity

Treasury Management on S/4HANA

In terms of selecting the right platform for treasury management on S/4HANA, there are many considerations, and the needs of each organization will differ. SAP has been working to ensure that the Public Cloud for Treasury Management has wider instrument coverage for corporate customers.

A development that could notably sway more corporates to consider the cloud-based options, is the inclusion of the new in-house banking component in the best practice offering from August 2022. In this module, which is embedded into Advanced Payment Management, SAP offers a completely rewritten solution, with advantages even over the traditional In-House Cash (IHC) module. IHC was previously not available to Public Cloud customers and this gap in the offering has no-doubt been a factor in customers deciding not to select the Public Cloud edition. These larger companies often need the payment functionalities available within IHC (such as payments on Behalf of, routing and internal transfers) and the lack of them is limiting. The addition of the in-house banking component makes for a more complete in-house bank functionality when paired with Advanced Payment Management (which is a prerequisite) and Treasury and Risk Management. This new in-house banking solution will also be made available to On-Premise customers during 2022 and with improved features and functionality, should be considered during upgrade decisions.

In Cash Management, S/4HANA Cloud comes standard with Basic Cash Management (Basic Bank Account Management and Basic Cash Operations). Advanced Cash Management, which delivers essentially the same as the On-Premise edition, barring one or two smaller features, is available, although an additional license is required. Liquidity Planning is only available if a customer has an SAP Analytics Cloud license.

SAP Treasury & Risk Management (TRM) is where the most differences currently exist between the Public Cloud and the Private Cloud or On-Premise editions. The Public Cloud has less instruments that are supported, although SAP is continually adding to the list.

Looking at the other most notable differences per area in TRM, the impact of the following in respect of the Public Cloud version should be discussed further with the customer:

- Hedge management – Reference-based hedging is currently not supported.

- Risk analyzers – Portfolio Analyzer is not offered, and SAP has no plans to include it. This is not generally required by corporate treasuries, so should not be an issue if the Public Cloud is selected.

- Securities – the offering is limited, although SAP is working to bridge the gaps. Asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities will be available in the August 2022 release.

- Derivatives – only interest rate swaps and cross currency swaps are possible, with no option to configure your own instruments.

- Position management – limited due to the reduced scope of instruments available in the cloud.

- Treasury analytics – FX reporting in SAP Analytics Cloud is limited but is being improved and customers can expect FX Hedging Area reports to be available by early 2023.

Making the Choice

Based on the above, the Public Cloud option makes sense for new businesses or smaller organizations that do not have the budget or resources to implement and support a customized solution. It would also suit organizations that need their systems to be responsive to market changes. Content is delivered as-is from SAP with minimal customization options, however, the cost of ownership is lower. It should also be noted that currently the Public Cloud edition of S/4HANA has been configured with local requirements for 43 countries. No more countries will be added; however, SAP is working on a tool which will enable customers to copy an existing country and create the settings for an additional country. This feature should be released in 2023.

In terms of treasury management, the Public Cloud would suit organizations with a vanilla treasury function and those that are looking to do a completely new implementation with no need to migrate from an existing system. This option does, however, require what SAP calls a “cloud mindset”, where customers cannot expect the system to fit into their existing processes but instead should look at how their organizational requirements can be met by SAP’s standard offerings.

The On-Premise solution would better suit larger organizations with well-established IT infrastructure and resources, as well as businesses using a broad spectrum of financial instruments that require customization. The On-Premise solution gives the customer full control and maximum freedom in terms of content, configuration, and timings of upgrades although there is a higher cost of ownership.

An attractive choice in the treasury space particularly is the hybrid one, i.e., the Private Cloud. Here customers would outsource their infrastructure management to SAP or another third party, whilst still ensuring they have the flexibility of options around treasury management scope.

With the Private Cloud and On-Premise, customers can still make use of Best Practice content as an accelerator. This content is available online for download and contains the likes of Process Flow diagrams and Test Scripts, helping customers to save time in an implementation. The Cloud’s Starter system is also provided as a way to see content before needing to configure it, thereby allowing the customer to test functionality upfront.

Zanders has in-depth knowledge and experience of Treasury Management on SAP S/4HANA and can help customers to analyze their requirements and ensure they make the best selection between Public Cloud, Private Cloud and On-Premise, or even a combination of the options.

Vendor Supply Chain Finance (SCF) constitutes the transfer of a (trade) payable position towards the SCF underwriter (i.e. the bank). The beneficiary of the payment can then decide either to receive an invoice payment on due date or to receive the funds before, at the cost of a pre-determined fee.

The debtor’s bank account will only be debited on due date of the payable; hence the bank finances the differential between the due date and the actual payment date towards the beneficiary for this pre-determined fee. This article elaborates on why and how corporates set-up an SCF scheme with their suppliers.

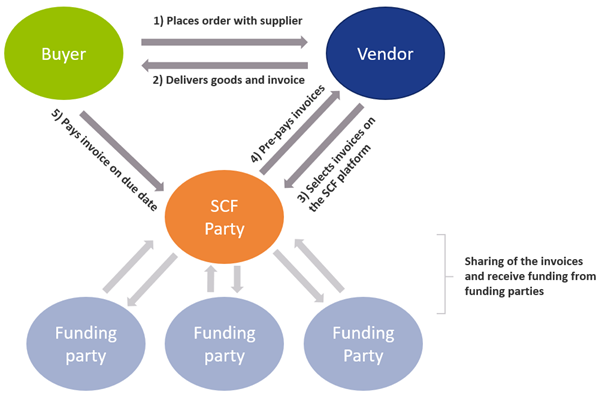

The Vendor SCF construction can be depicted as:

There are multiple business rationales behind Supply Chain Finance. Why would a corporate want to setup an SCF scheme with its suppliers? The most prominent rationales are:

- Reduction of the need of more traditional trade finance

The need for individual line of credits and bank guarantees for each trade transaction is removed, making the trade process more efficient. - Sellers can flexibly and quickly fund short term financing needs

If working capital or financing is needed, the seller can quickly request for outstanding invoices to be paid out early (minus a fee). - Sharing the benefits of better credit rating from buyer towards seller

Because the financing is arranged by the buyer, the seller can enjoy the credit terms that were negotiated between buyer and financier/bank. - Streamlining the AP process

By onboarding various vendors into the SCF process, the buyer can enjoy a singular and streamlined payment process for these vendors. - Strengthening of trade relations

Because of the benefits of SCF, more competitive terms on the trade agreement itself can be negotiated.

SCF is typically considered a tool to improve the working capital position of a company, specifically to decrease the cash conversion cycle by increasing the payment terms with its suppliers without weakening the supply chain.

Set-up and onboarding

Typically, a set-up and onboarding process consists of the following steps. First a financing for SCF is obtained from, for example, a bank. In addition, an SCF provider must be selected and contracted. Most major banks have their own solutions but there are many third parties, for example fintechs, that provide solutions as well. Consequently, the SCF terms are negotiated, and the suppliers are onboarded to the SCF process. Lastly, your system should of course be able to process/register it. Therefore, the ERP accounts payable module needs to be adjusted, such that the AP positions eligible for SCF are interfaced into the SCF platform. Besides, your ERP system needs to be adjusted to be able to reconcile the SCF reports and bank statements.

Design considerations and Processing SCF in SAP

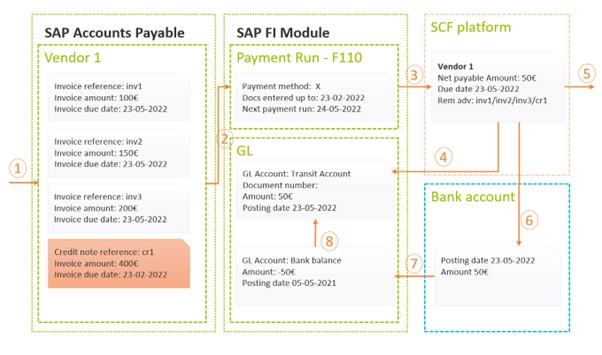

In the picture below we provide a high-level example of how a basic SCF process can work using basic modules in SAP. Note that, based on the design considerations and capabilities of the SCF provider, the picture may look a bit different. For each of the steps denoted by a number, we provide an explanation below the figure, going a little deeper into some of the possible considerations on which a decision must be made.

- Invoice and credit note data entry; In the first step, the invoices/credit notes will be entered, typically with payment terms sometime in the future, i.e. 90 days. Once entered and approved, these invoices are now available to the payment program.

- Payment run: The payment run needs to be engineered such that the invoices that are due in the future (i.e. 90 days from now) will be picked up already in today’s run. Some important considerations in this area are:

- Payment netting logic: the netting of invoices and credit notes is an important design consideration. Typically, credit notes are due immediate and the SCF invoices are due sometime in the future, i.e. 90 days from now. If one would decide to net a credit note due immediate with an invoice due in 90 days, this would have some adverse impact on working capital. An alternative is to exclude credit notes from being netted with SCF invoices and have them settled separately (i.e. request the vendor to pay it out separately or via a direct debit). Additionally, some SCF providers have certain netting logic embedded in their platform. In this case, the SAP netting logic should be fully disabled and all invoices should be paid out gross. Careful considerations should be taken when trying to reconcile the SCF settled items report as mentioned in step 4 though.

- Payment run posting: When executing the SAP payment run it is possible to either clear the underlying invoices on payment run date or to leave them open until invoice due date. If the invoices are kept open, they will be cleared once the SCF reporting is imported in SAP (see step 4). This is decision-driven by the accounting team and depends on where the open items should be rolling up in the balance sheet (i.e. payable against the vendor or payable against the SCF supplier).

- Payment file transfer: At this step, the payment file will be generated and sent to the SCF supplier. The design considerations are dependent on the SCF supplier’s capabilities and should be considered carefully while selecting an appropriate partner.

- File format: Most often we advise to implement a best practice payment file format like ISO pain.001. This format has a logical structure, is supported out of the box in SAP, while most SCF partners will support it too.

- Interface technology: The payment files need to be transferred into the SCF platform. This can be done via a multitude of ways; i.e. manual upload, automatically via SWIFT or Host2Host. This decision is often driven internally. Often the existing payment infrastructure can be leveraged for SCF payments as well.

- Remittance information: By following ISO pain.001 standard, the remittance information that remits which invoices are paid and cleared, can be provided in a structured format, irrespective of the volume of invoices that got cleared. This ensures that the beneficiary exactly knows which invoices were paid under this payment. Alternatively, an unstructured remittance can be provided but this often is limited to 140 characters maximum.

- Payment status reporting: Some SCF supplier will support some form of payment status reporting to provide immediate feedback on whether the payments were processed correctly. These reports can be imported in SAP; SAP can subsequently send notifications of payment errors to the key users who can then take corrective actions.

- SCF payment clearing reporting: At this step, the SCF platform will send back a report that contains information on all the cleared payments and underlying invoices for that specific due date. Most typically, these reports are imported in SAP to auto reconcile against the open items sitting in the administration.

- Auto import: If import of the statement into SAP is required, the report should be in one of SAP’s standard-supported formats like MT940 or CAMT.053.

- Auto reconciliation: If auto reconciliation of this report against line items in SAP is required, the reports line items should be matchable with the open line items in the SAP administration. Secondly, a pre-agreed identifier needs to be reported such that SAP can find the open item automatically (i.e. invoice reference, document number, end2endId, etc.). Very careful alignment is needed here, as slight differences in structure in the administration versus the reporting structure of SCF can lead to failed auto reconciliation and tedious manual post processing.

- Pay out to the beneficiary: Onboarded vendors can access the SCF platform and report on the pending payments and invoices. The vendor has the flexibility to have the invoices paid out early (before due date) by accepting the deduction of a pre-agreed fee. The SCF provider should ensure payment is made.

- Debiting bank account: At due date of the original invoice, the SCF provider will want to receive the funds.

- Payment initiation vs direct debit: The payment of funds can in principle be handled via two processes; either the SCF customer initiates the payment himself, or an agreement is made that the SCF provider direct debits the account automatically.

- Lump debit vs line items: Most typically, one would make a lump payment (or direct debit) of the total amount of all invoices due on that day. Some SCF providers may support line by line direct debiting although this might result in high transaction costs. Line by line debiting might be beneficial for the auto reconciliation process in SAP though (see step 7)

- Bank statement reporting: The bank statement of the cash account will be received and imported into SAP. Most often, the statements are received over the existing banking interface.

- Bank statement processing: Based on pre-configured posting rules and reconciliation algorithms in SAP, the open items in the administration are cleared and the bank balance is updated appropriately.

To conclude

If the appropriate SCF provider is selected and the process design and implementation in SAP is sound, the benefits of SCF can be achieved without introducing new processes and therefore creating a burden on the existing accounts payable team. It is fully possible to integrate the SCF processes with the regular accounts payable payments processes without adding additional manual process steps or cumbersome workarounds.

For more information, contact Ivo Postma at +31 88 991 02 00.

FRTB PLA’s catch-22: hedging, used to reduce a portfolio’s risk, may actually increase the likelihood of failing the PLA test.

Profit and loss attribution (PLA) is a critical component of FRTB’s internal models approach (IMA), ensuring alignment between Front Office (FO) and Risk models. The consequences of a PLA test failure can be severe, with desks forced to use the more punitive standardised approach (SA), resulting in a considerable increase in capital charges. The introduction of the PLA test has sparked controversy as it appears to disincentivise the use of hedging. Well-hedged portfolios, which reduce risk and variability in a portfolio's P&L, often find it more challenging to pass the PLA test compared to riskier, unhedged portfolios.

In this article, we dig deeper into the issues surrounding hedging with the PLA test and provide solutions to help improve the chances of passing the test.

The problem with performing PLA on hedged portfolios

The PLA test measures the compatibility of the risk theoretical P&L (RTPL), produced by Risk, with the hypothetical P&L (HPL) produced by the FO. This is achieved by measuring the Spearman correlation and Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test statistic on 250 days of historical RTPLs and HPLs for each trading desk. Based on the results of these tests, desks are assigned a traffic light test (TLT) zone categorisation, defined below. The final PLA result is the worst TLT zone of the two tests.

| TLT Zone | Spearman Correlation | KS Test |

| Green | > 0.80 | < 0.09 |

| Amber | < 0.80 | > 0.09 |

| Red | < 0.70 | > 0.12 |

The impact of TLT zones

The impact of a desk’s PLA results depends on which TLT zone it has been assigned:

- Green zone: Desks are free to calculate their capital requirements using the IMA.

- Amber zone: Desks are required to pay a capital surcharge, which can lead to a considerable increase in their capital requirements.

- Red zone: Desks must calculate their capital requirements using the SA, which can lead to a significant increase in their capital.

Red and Amber desks must also satisfy 12-month backtesting exception requirements before they can return to the green zone.

Why are hedged portfolios more susceptible to failing the PLA test?

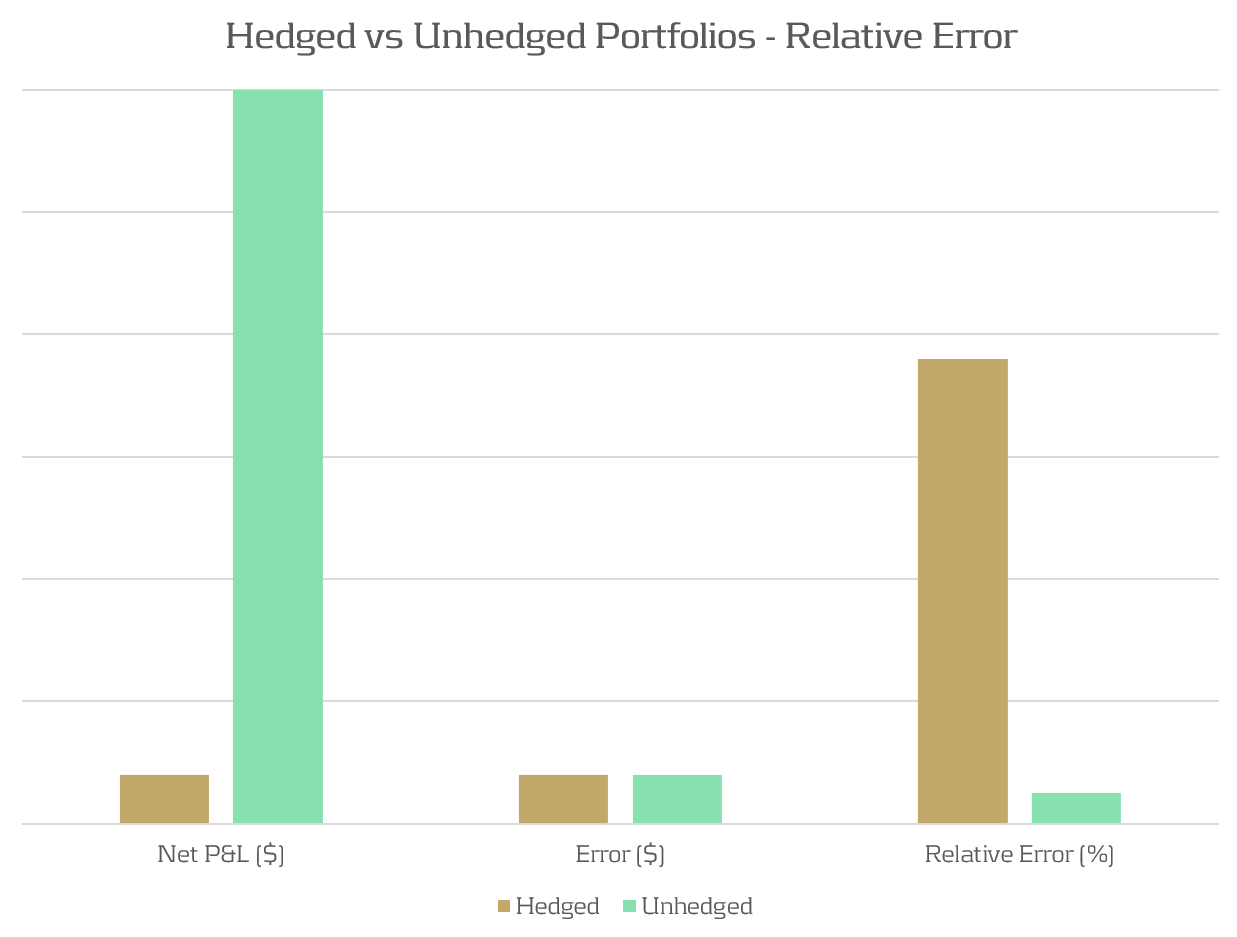

Due to modeling and data differences, we typically expect there to exist a small difference (error) between RTPLs and HPLs. For unhedged portfolios, the total P&L is typically much larger than this error, resulting in a small relative error. When portfolios are hedged, the total P&L of the portfolio is reduced, leading to a larger relative error than that of an unhedged portfolio. This is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows how for the same modeling error, a significantly different relative error can be observed, depending on the degree of hedging of the portfolios.

Figure 1: The relative P&L error can be significantly different between hedged and unhedged portfolios which have the same absolute error.

Demonstration: A delta-hedged option portfolio

Portfolio and simulation

To demonstrate the PLA hedging issue, we examine a simulated example of a desk with long put positions, hedged by a variable quantity of the underlying stock. In this example, the portfolio consists of 100 long puts and between 0 and 100 of the underlying stock as a hedge against the put positions.

To emulate the differences in pricing models between Risk and FO, a closed form solution is used to compute HPLs and a Monte Carlo pricing methodology is used for RTPLs. This produces a sufficiently small pricing error, such that the options and stock positions would comfortably pass the PLA test if they were held in separate portfolios. The P&Ls are obtained by repricing 250 scenarios of a Monte Carlo simulation of the underling risk factors.

The outcome

The results in Figure 2 show the PLA results for the two statistical tests against the total hedge ratio (the ratio between stock position delta and put position delta). The TLT zones are represented by the green, amber, and red shaded regions. This shows that the test statistics can vary quite considerably depending on the degree of hedging, with the KS test statistic entering the amber and red TLT zones for even a limited degree of hedging. The Spearman correlation is not as sensitive to the hedge ratio, but the statistic worsens as the hedging ratio approaches 100%.

Although the portfolio comfortably passes the PLA test when unhedged, it fails when hedged. Hence, quite surprisingly, hedging strategies used by banks to reduce risk may in fact be penalised by the regulator and increase capital requirements. Furthermore, failing desks would also need to satisfy 12-month PLA and backtesting requirements to return to the IMA.

Figure 2: The KS (top) and Spearman correlation (bottom) statistics for an example portfolio of 100 long puts and between 0 and 100 shares of the underlying stock. The hedge ratio is defined as the ratio between stock position delta and put position delta. The green, amber, and red shading represent the TLT zones.

Solutions for Hedged Portfolios

Reducing the impact of hedged portfolios

As demonstrated, some trading desks with well-hedged positions may find themselves losing IMA eligibility due to poor performance in the PLA test. However, the following strategies can be used to reduce the possibility of failures:

- Model Alignment: Ensure the modeling methodologies of risk factors and instrument pricing are consistent between FO and Risk.

- Data Alignment: Ensure that the data sourced for FO and Risk are aligned and are of similar quality and granularity.

- Risk Enhancements: Improve the sophistication of Risk pricing models to better incorporate the subtilities of the FO pricer. This may require pricing optimisations and high-performance computing.

- Proactive Monitoring: Develop ongoing monitoring frameworks to identify and remediate P&L issues early. We provide more insights on the development of PLA analytics here.

Will regulatory policy change be required?

It is clear that the current PLA regulation does not correctly account for the effects of hedging on the PLA test statistics, resulting in hedged portfolios being penalised. As banks move towards implementing FRTB IMA, regulators should reflect on the impact of the current PLA implementation and consider providing exemptions for hedged portfolios or, alternatively, a fundamental modification of the PLA test.

Zanders’ services

Zanders is ideally suited to helping clients develop models and implement FRTB workstreams. Below, we highlight a selection of the services we provide to implement, analyse, and improve PLA test results:

Conclusion

The PLA test under FRTB can disproportionately penalise well-hedged portfolios, forcing trading desks to adopt the more punitive SA. This effect is exacerbated by complex hedging strategies and non-linear instruments, which introduce additional model risks and potential discrepancies. To mitigate these issues, it is essential banks take steps to align their pricing models and data between FO and Risk. Implementing robust analytics frameworks to identify P&L misalignments is critical to quicky and proactively solve PLA problems. Zanders offers comprehensive services to help banks navigate the complexities of PLA and optimise their regulatory capital requirements.

For more information on this topic, contact Dilbagh Kalsi (Partner) or Hardial Kalsi (Manager).

The corporate landscape is being redefined by a plethora of factors, from new business models and changing regulations to increased competition from digital natives and the acceleration of the consumer digital-first mindset.

The new landscape is all about a digital real-time experience which is creating the need for change in order to stay relevant and ideally thrive. If we reflect on the various messages from the numerous industry surveys, it’s becoming crystal clear that a digital transformation is now an imperative.

We are seeing an increasing trend that recognizes technological progress will fundamentally change an organization and this pressure to move faster is now becoming unrelenting. However, to some corporates, there is still a lack of clarity on what a digital transformation actually means. In this article we aim to demystify both the terminology and relevance to corporate treasury as well as considering the latest trends including what’s on the horizon.

What is digital transformation?

There is no one-size-fits-all view of a digital transformation because each corporate is different and therefore each digital transformation will look slightly different. However, a simple definition is the adoption of the new and emerging technologies into the business which deliver operational and financial efficiencies, elevate the overall customer experience and increase shareholder value.

Whilst these benefits are attractive, to achieve them it’s important to recognize that a digital transformation is not a destination – it’s a journey that extends beyond the pure adoption of technology. Whilst technology is the enabler, in order to achieve the full benefits of this digital transformation journey, a more holistic view is required.

Figure 1 provides a more holistic view of a digital transformation, which embraces the importance of cultural change like the adoption of the ‘fail fast’ philosophy that is based on extensive testing and incremental development to determine whether an idea has value.

In terms of the drivers, we see four core pillars providing the motivation:

- Elevate the customer experience

- Operational agility and resilience

- Data driven real time vision

- Workforce enablement

Figure 1: Digital Transformation View

What is the relevance to corporate treasury?

Considering the digital transformation journey, it’s important to understand the relevance of the technologies available.

Whilst figure 2 highlights the foundational technologies, it’s important to note that these technologies are all at a different stage of evolution and maturity. However, they all offer the opportunity to re-define what is possible, helping to digitize and accelerate existing processes and elevate overall treasury performance.

Figure 2: Core Digital Transformation Technologies

To help polarize the potential application and value of these technologies, we need to look through two lenses.

Firstly, what are some of today’s mainstream challenges that currently impact the performance of the treasury function, and secondly, how these technologies provide the opportunity to both optimize and elevate the treasury function.

The challenges and opportunities to optimize

Considering some of the major challenges that still exist within corporate treasury, the new and emerging technologies will provide the foundation for the digital transformation within corporate treasury as they will deliver the core capabilities to elevate overall performance. Figure 3 below provides some insights into why these technologies are more than just ‘buzzwords’, providing a clear opportunity to elevate current performance.

Figure 3: Common challenges within corporate treasury

Cognitive cash flow forecasting systems can learn and adapt from the source data, enabling automatic and continuous improvements in the accuracy and timeliness of the forecasts. Additionally, scenario analysis accelerates the informed decision-making process. Focusing on currency risk, the cognitive technology is on a continuous learning loop and therefore continues to update its decision-making process which helps improve future predictions.

Moving onto working capital, these new cognitive technologies combined with advanced optical character recognition/intelligent character recognition can automate and accelerate key processes within both the accounts payables (A/P) and account receivables (A/R) functions to contribute to overall working capital management. On the A/R side, these technologies can read PDF and email remittance information as well as screen scrape data from customer portals. This data helps automate and accelerate the cash application process with levels exceeding 95% straight through reconciliation now being achieved. Applying cash one day earlier has a direct positive impact on days sales outstanding (DSO) and working capital. On the A/P side, the technology enables greater compliance, visibility and control providing the opportunity for ‘autonomous A/P’. With invoice approval times now down to just 10.4 business hours*, it provides a clear opportunity to maximize early payment discounts (EPDs).

Whilst artificial intelligence/machine learning technologies will play a significant role within the corporate treasury digital transformation, the increased focus on real-time treasury also points to the power of financial application program interfaces (APIs). API technology will play an integral part of an overall blended solution architecture. Whilst API technology is not new, the relevance to finance really started with Europe’s PSD2 (Payment Services Directive 2) Open Banking initiative, with API technology underpinning this. There are already several use cases for both Treasury and the SSC (shared service center) to help both digitize and importantly accelerate existing processes where friction currently exists. This includes real time balances, credit notifications and payments.

The latest trends

Whilst a number of these new and emerging technologies are expected to have a profound impact on corporate treasury, when we consider the broader enterprise-wide adoption of these technologies, we are generally seeing corporate treasury below these levels. However, in terms of general market trends we see the following:

- Artificial intelligence/machine learning is being recognized as a key enabler of strategic priorities, with the potential to deliver both predictive and prescriptive analytics. This technology will be a real game-changer for corporate treasury not only addressing a number of existing and longstanding pain-points but also redefining what is possible.

- Whilst robotic process automation (RPA) is becoming mainstream in other business areas, this technology is generally viewed as less relevant to corporate treasury due to more complex and skilled activities. That said, Treasury does have a number of typically manually intensive activities, like manual cash pooling, financial closings and data consolidations. So, broader adoption could be down to relative priorities.

- Adoption of API technology now appears to be building momentum, given the increased focus around real time treasury. This technology will provide the opportunity to automate and accelerate processes, but a lack of industry standardization across financial messaging, combined with the relatively slow adoption and limited API banking service proposition across the global banking community, will continue to provide a drag on adoption levels.

What is on the horizon?

Over the past decade, we have seen a tsunami of new technologies that will play an integral part in the digital transformation journey within corporate treasury. Given that, it has taken approximately ten years for cloud technology to become mainstream from the initial ‘what is cloud?’ to the current thinking ‘why not cloud?’ We are currently seeing the early adoption of some of these foundational transformational technologies, with more corporates embarking on a digital first strategy. This is effectively re-defining the partnership between man and machine, and treasury now has the opportunity to transform its technology, approach and people which will push the boundaries on what is possible to create a more integrated, informed and importantly real-time strategic function.

However, whilst these technologies will be supporting critical tasks, assisting with real-time decision-making process and reducing risk, to truly harness the power of technology a data strategy will also be foundational. Data is the fuel that powers AI, however most organizations remain heavily siloed, from a system, data, and process perspective. Probably the biggest challenge to delivering on the AI promise is access to the right data and format at the right time.

So, over the next 5-10 years, we expect the solutions underpinned by these new foundational technologies to evolve, leveraging better quality structured data to deliver real time data visualization which embraces both predictive and prescriptive analytics. What is very clear is that this ecosystem of modern technologies will effectively redefine what is possible within corporate treasury.

*) Coupa 2021 Business Spend Management Benchmark Report

Amidst the aftermath of the corona pandemic and the unfolding tragedy in Ukraine, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its latest report1 on climate change on 28 February 2022, containing a more alarming message than ever before.

The Working Group II contribution to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report states that “climate change is a grave and mounting threat to our wellbeing and a healthy planet”. It is a formidable, global challenge to transition to a sustainable economy before time is running out. Banks have an important role to play in this transition. By stepping up to this role now, banks will be better prepared for the future, and reap the benefits along the way.

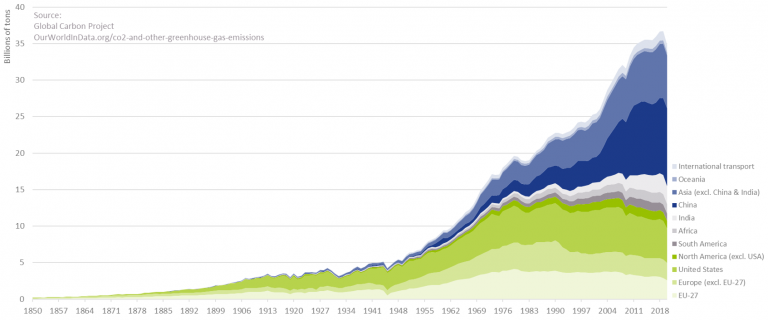

In the Paris Agreement (or COP21), adopted in December 2015, 196 parties agreed to limit global warming to well below 2.0°C, and preferably to no more than 1.5°C. To prevent irreversible impacts to our climate, the IPCC stresses that the increase in global temperature (relative to the pre-industrial era) needs to remain below 1.5°C. To achieve this target, a rapid and unprecedented decrease in the emission of greenhouse gasses (GHG) is required. With CO2 emissions still on the rise, as depicted in Figure 1, the challenge at hand has increased considerably in the past decade.

Figure 1 – Annual CO2 emissions from fossil fuels.

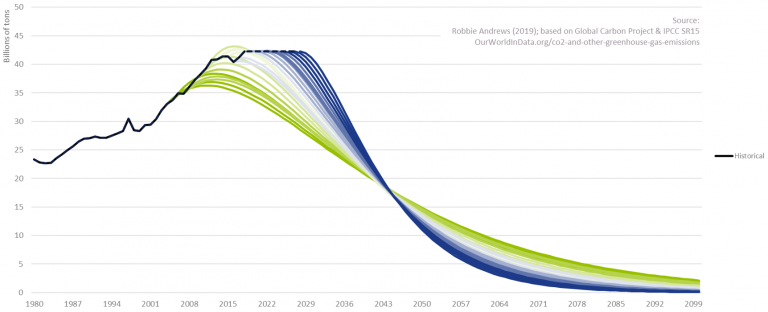

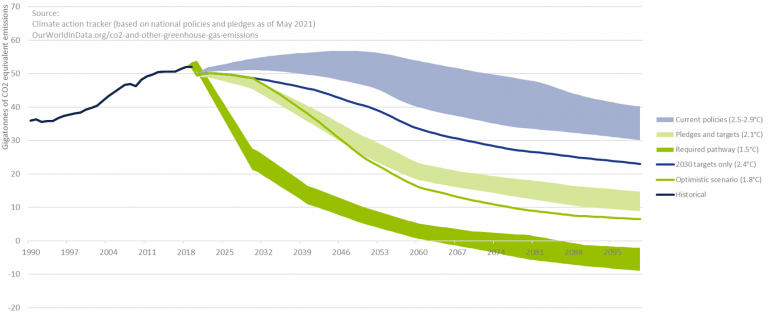

To further illustrate this, Figure 2 depicts for several starting years a possible pathway in CO2 reductions to ensure global warming does not exceed 2.0°C. Even under the assumption that CO2 emissions have already peaked, it becomes clear that the required speed of CO2 reductions is rapidly increasing with every year of inaction. We are a long way from limiting global warming to 2.0°C. This even holds under the assumption that all countries’ pledges to reduce GHG emissions will be achieved, as can be observed in Figure 3.

To quote the IPCC Working Group II co-chair Hans-Otto Pörtner: “Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all.”

Figure 2 – CO2 reduction need to limit global warming.

Figure 3 – Global GHG emissions and warming scenario’s.

The role of banks in the transition – and the opportunities it offers

Historically, banks have been instrumental to the proper functioning of the economy. In their role as financial intermediaries, they bring together savers and borrowers, support investment, and play an important role in facilitating payments and transactions. Now, banks have the opportunity to become instrumental to the proper functioning of the planet. By allocating their available capital to ‘green’ loans and investments at the expense of their ‘brown’ counterparts, banks can play a pivotal role in the transition to a sustainable economy. Banks are in the extraordinary position to make a fundamentally positive contribution to society. And even better, it comes with new opportunities.

The transition to a sustainable economy requires huge investments. It ranges from investments in climate change adaption to investments in GHG emission reductions: this covers for example investments in flood risk warning systems and financing a radical change in our energy mix from fossil-fuel based sources (like coal and natural gas) to clean energy sources (like solar and wind power). According to the Net Zero by 2050 Report from the International Energy Agency (IEA)2, the annual investments in the energy sector alone will increase from the current USD 2.3 trillion to USD 5.0 trillion by 2030. Hence, across sectors, the increase in annual investments could easily be USD 3.0 to 4.0 trillion. As much as 70% of this investment may need to be financed by the private sector (including banks and other financial institutions)3. To put this in perspective, the total outstanding credit to non-financial corporates currently stands at USD 86.3 trillion4. Assuming an average loan maturity of 5 years, this would translate to a 12-16% increase in loans and investments by banks on a global level. Hence, the transition to a sustainable economy will open up a large market for banks through direct investments and financing provided to corporates and households.

The transition to a sustainable economy is also triggering product development. The Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) for example reports that the combined issuance of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) bonds, sustainability-linked bonds and transition debt reached almost USD 500 billion in 2021H1, representing a 59% year-on-year growth rate. Other initiatives include the introduction of ‘green’ exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and sustainability-linked derivatives. The latter first appeared in 2019 and they provide an incentive for companies to achieve sustainable performance targets. If targets are met, a company is for example eligible for a more attractive interest coupon. Again, this is creating an interesting market for banks.

By embracing the transition, with all the opportunities that it offers, banks are also bracing themselves for the future. Banks that adopt climate change-resilient business models and integrate climate risk management into their risk frameworks will be much better positioned than banks that do not. They will be less exposed to climate-related risks, ranging from physical and transition risks to risks stemming from a reputational perspective or litigation, also justifying lower capital requirements. The early adaptors of today will be the leaders of tomorrow.

A roadmap supporting the transition

How should a bank approach this transition? As depicted in Figure 4, we identify four important steps: target setting, measurement and reporting, strategy and risk framework, and engaging with clients.

Figure 4 – The roadmap supporting the transition to a sustainable economy.

Target setting

The starting point for each transition is to set GHG emission targets in alignment with emission pathways that have been established by climate science. One important initiative that can support banks in setting these targets is the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). This organization supports companies to set targets in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Unlike many other companies, the majority of a bank’s GHG emissions are outside their direct control. They can influence, however, their so-called financed emissions, which are the GHG emissions coming from their lending and investment portfolios. The SBTi has developed a framework for banks that reflects this. It encourages banks to use the Absolute Contraction approach that requires a 2.5% (for a well-below 2.0°C target) or 4.2% (for a 1.5°C target) annual reduction in GHG emissions. A clear emission pathway guides banks in the subsequent steps of the transition process.

Measurement and reporting

With targets in place, the next important step for a bank is to determine their level of GHG emissions: both for scope 1 and 2 (the GHG emissions they control) and for scope 3 (the financed emissions). Important initiatives for the quantification of the financed emissions are the Paris Agreement Capital Transition Assessment (PACTA) and the Platform Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF). PCAF is a Dutch initiative to deliver a global, standardized GHG accounting and reporting approach for financial institutions (building on the GHG Protocol). PACTA enables banks to measure the alignment of financial portfolios with climate scenarios.

By keeping track of the level of GHG emissions on an annual basis, banks can assess whether they are following their selected emission pathway. Reporting, in line with the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), will contribute to a greater understanding of climate risks with their investors and other stakeholders.

Strategy and risk framework

Setting targets and measuring the current level of GHG emissions are necessary but not sufficient conditions to achieve a successful transition. Climate change risk needs to be fully integrated into a bank’s strategy and its risk framework. To assess the climate change-resilience of a bank’s strategy, a logical first step is to understand which climate change risks are material to the organization (e.g., by composing a materiality matrix). Subsequently, studying the transmission channels of these risks using scenario analysis and/or stress testing creates an understanding of what parts of the business model and lending portfolio are most exposed. This could lead to general changes in a bank’s positioning, but these risks should also be factored into the bank’s existing risk framework. Examples are the loan origination process, capital calculations, and risk reporting.

Engaging with clients

A fourth step in the game plan to successfully support the transition is for a bank to actively engage with its clients. A dialogue is required to align the bank’s GHG emission targets with those of its clients. This extends to discussing changes in the operations and/or business model of a client to align with a sustainable economy. This also may include timely announcing that certain economic activities will no longer be financed, and by financing client’s initiatives to mitigate or adapt to climate change: e.g., financing wind turbines for clients with energy- or carbon-intensive production processes (like cement or aluminium) or financing the move of production locations to less flood-prone areas.

Conclusion

Banks are uniquely positioned to play a pivotal role in the transition to a sustainable economy. The transition is already providing a wide range of opportunities for banks, from large financing needs to the introduction of green bonds and sustainability-linked derivatives. At the same time, it is of paramount importance for banks to adopt a climate change-resilient strategy and to integrate climate change risk into their risk frameworks. With our extensive track record in financial and non-financial risk management at financial institutions, Zanders stands ready to support you with this ambitious, yet rewarding challenge.

ESG risk management and Zanders

Zanders is currently supporting several clients with the identification, measurement, and management of ESG risks. For a start, we are supporting a large Dutch bank with the identification of ESG risk factors that have a material impact on the credit risk profile of its portfolio of corporate loans. The material risk factors are then integrated in the bank’s existing credit risk framework to ensure a proper management of this new risk type.

We are supporting other banking clients with the quantification of climate change risk. In one case, we are determining climate change risk-adjusted Probabilities of Default (PDs). Using expected future emissions and carbon prices based on the climate change scenarios of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), company specific shocks based on carbon prices and country specific shocks on GDP level are determined. These shocked levels are then used to determine the impact on the forecasted PDs. In another case, we are investigating the potential impact of floods and droughts on the collateral value of a portfolio of residential mortgage loans.

We also gained experience with the data challenges involved in the typical ESG project: e.g., we are supporting an asset manager with integrating and harmonizing ESG data from a range of vendors, which is underlying their internally developed ESG scores. We also support them with embedding these scores in the investment process.

With our extensive track record in financial and non-financial risk management at financial institutions in general, and our more recent ESG experience, Zanders stands ready to support you with the ambitious, yet rewarding challenge to adopt a climate change-resilient strategy and to integrate climate change risk in your existing risk frameworks.

Foot notes:

1 The IPCC Working Group II contribution: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.

2 The IEA report, Net Zero by 2050.

3 See the Net Zero Financing roadmaps from the UN, ‘Race to Zero’ and the ‘Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero’ (GFANZ).

4 Based on the statistics of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) per 2021-Q3.

5 The Climate Bonds Initiative’s Sustainable Debt Highlights H1 2021.

Royal FloraHolland has been on a journey to optimize their cash management processes.

With a complex landscape consisting of two SAP systems and several banks, the choice was made to implement SWIFT’s Alliance Lite 2 functionality.

This new standardized approach to bank connectivity has enabled Royal FloraHolland to connect with new banks, and in addition, the embedded payment approval workflow within AL2 provides the opportunity for Royal FloraHolland to carry out a final control before releasing payment and collection files to their partner banks. Unfortunately, this final control process was highly dependent on manual activities, where files were retrieved from folders within SAP environments and subsequently uploaded into AL2. Despite these payment and collection files being authorized after being uploaded into AL2, the fact that they are downloaded to a user’s personal desktop has always been a risk from an audit and control perspective. Royal FloraHolland wanted to mitigate the risk of human error and remove the vulnerability of the files in transit.

Considerations

After carrying out a short assessment of available solutions on the market, ranging from payment hub providers to full blown SWIFT Service Bureaus, Royal FloraHolland decided to explore options towards developing a solution in house. This was motivated by the fact that Royal FloraHolland had already invested in a generic bank connectivity solution. Their requirements were simple; namely that payment and collection files must be transferred to AL2 in a secure manner without any human intervention. In this context, the minimum security requirements must not allow following:

- Files to be manipulated in the transit between SAP and AL2

- The injection of files from sources other than the (production) SAP system

Solution

SWIFT Autoclient is a SWIFT solution that allows clients to automatically upload/download files to/from AL2. Royal FloraHolland was already using Autoclient to automatically download their bank statements from AL2, however they were not currently leveraging on the automatic file upload capabilities offered by Autoclient. When using the upload functionality, there are a few things that should be considered.

Firstly, it is important to consider the vulnerability of files in transit. Autoclient uploads files automatically to SWIFT AL2 once they are placed in the configured source directory. To avoid the risk of processing files that have either been manipulated or have originated from a non-trusted source system, Autoclient offers the option to secure files using LAU (Local Authentication). This method ensures a secure transfer of (payment) files between backend applications and Autoclient by calculating an electronic signature over the file. This signature is then transferred together with the file to Autoclient and verified. Only files that have been successfully verified will be transferred into AL2. This method requires a symmetric key infrastructure, whereby the secret key used to calculate the electronic signature is the same key used to verify the signature, meaning there is a requirement to maintain the secret key in both the source (SAP) application and in Autoclient. Since this deviates from SAP standard functionality, a bespoke development was required, alongside the additional logic to calculate the LAU signature.

Secondly, the routing of outgoing payment files needs to be managed. When uploading payment files to AL2 there is a requirement to transfer the relevant parameters for FileAct traffic. Normally, this can be achieved by using the Autoclient configuration options, however, when using LAU, SWIFT recommends its customers to provide the FileAct parameters together with a payment file. To fulfil this requirement a transaction was built in SAP to maintain these parameters. A clear advantage of this transaction is that the connection to new partner banks can now be managed fully via configuration in the SAP systems. There is no immediate requirement for further updates in Autoclient or AL2 as the parameter files supplied already contain all required routing information.

A third hurdle to overcome is the approval workflow within AL2. By default, AL2 will deliver files that are uploaded via Autoclient directly to partner banks. Any verification and authorization steps in AL2 will be bypassed. Royal FloraHolland wanted an additional authentication workflow to be active in AL2, which included files uploaded via Autoclient. As this requirement deviates from the standard functionality offered by AL2, a change request was raised to SWIFT, who developed and implemented this logic.

Implementation

The new solution was developed such that there was no impact on the existing file transfer process. This allowed Royal FloraHolland to perform a dry run in the production system using a limited number of payments, to ensure that the new solution is working as designed.

Conclusion

Royal FloraHolland is now running their payments and collections in an automated way. Not only has this reduced the workload burden for the AP department but has increased confidence that payments arriving in AL2 are from a trusted source.

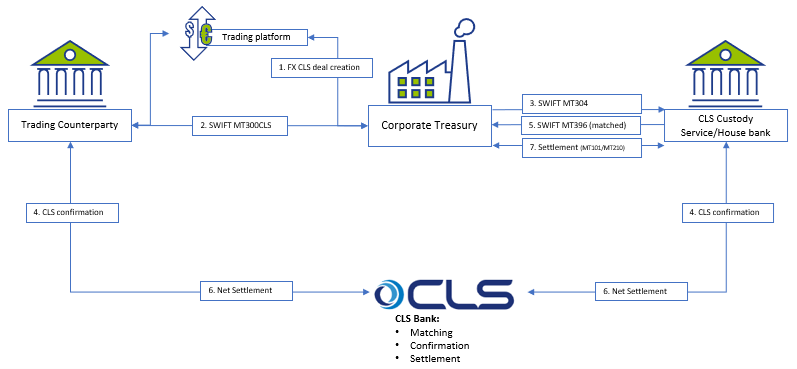

Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS) is an established global system to mitigate settlement risks for FX trades, improving corporate cash and liquidity management among other benefits.

The CLS system was established back in 2002 and since then, the FX market has grown significantly. Therefore, there is a high demand from corporates to leverage CLS to improve corporate treasury efficiency.

In this article we shed some light on the possible technical solutions in SAP Treasury to implement CLS in the corporate treasury operations. This includes CLS deal capture, limit utilization implications in Credit risk analyzer, and changes in the correspondence framework of SAP TRM.

Technical solution in SAP Treasury

There is no SAP standard solution for CLS as such. However, SAP standard functionality can be used to cover major parts of the CLS solution. The solution may vary depending on the existing functionality for hedge management/accounting and limit management as well as the technical landscape accounting for SAP version and SWIFT connectivity.

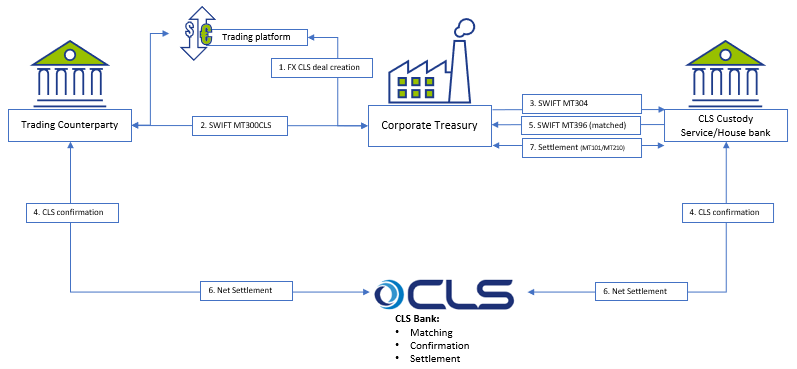

Below is a simplified workflow of CLS deal processing:

The proposed solution may be applicable for a corporate using SAP TRM (ECC to S/4HANA), having Credit risk analyzer activated and using SWIFT connection for connectivity with the banks.

Capturing CLS FX deals

There are a few options on how to register the FX deal as a CLS deal, with two described below:

Option 1: CLS Business partner – a replica of your usual business partner (BP) which would have CLS BIC code and complete settlement instructions.

Option 2: CLS FX product type/transaction type – a replica of normal FX SPOT, FX FORWARD or FX SWAP product type/transaction type.

Each option has pros and cons and may be applied as per a client technical specific.

FX deals trading and capturing may be executed via SAP Trade Platform Integration (TPI), which would improve the processing efficiency, but development may still be required depending on characteristics of the scope of FX dealing. In particular, the currency, product type, counterparty scope and volume of transactions would drive whether additional development is required, or whether standard mapping logic can be used to isolate CLS deals.

For the scenarios where a custom solution is required to convert standard FX deals into CLS FX deals during its creation, a custom program could be created that includes an additional mapping table to help SAP determine CLS eligible deals. The bespoke mapping table could help identify CLS eligibility based on the below characteristics:

- Counterparty

- Currency Pair

- Product Type (Spot, Forward, SWAP)

Correspondence framework

Once CLS deal is captured in SAP TRM, it needs to be counter-confirmed with the trading counterparty and with CLS Bank. Three new types of correspondence need to be configured:

- MT300 with CLS specifics to be used to communicate with the trading counterparty;

- MT304 to communicate with CLS Custody service;

- SWIFT MT396 to get the matching status from CLS bank.

Credit Risk Analyzer (CRA)

FX CLS deals do not bring settlement exposure, thus CLS deals need to be exempt from the settlement risk utilization. Configuration of the limit characteristics must include either business partner number (for CLS Business Partner) or transaction type (for CLS transaction type). This will help determine the limits without FX CLS deals.

No automatic limits creation should be allowed for the respective limit type; this will disable a settlement limit creation based on CLS deal capture in SAP.

CLS Business partner setting must be done with ‘parent <-> subsidiary’ relationship with the regular business partner. This is required to keep a single credit limit utilization and having FX deals being done with two business partners.

Deal execution

Accounting for CLS FX deals is normally the same as for regular FX deals, though it depends on the corporate requirements. We do not see any need for a separate FX unrealized result treatment for CLS deals.

However, settlement of CLS deals is different and standard settlement instructions of CLS deals vary from normal FX deals.

Either the bank’s virtual accounts or separate house bank accounts are opened to settle CLS FX deals.

Since CLS partner performs the net settlement on-behalf of a corporate there is no need to generate payment request for every CLS deal separately. Posting to the bank’s CLS clearing account with cash flow postings (TBB1) is sufficient at this level.

The following day the bank statement will clear the postings on the CLS settlement account on a net basis based on the total amount and posting date.

Cash Management

A liquidity manager needs to know the net result of the CLS deals in advance to replenish the CLS bank account in case the net settlement amount for CLS deal is negative. In addition, the funds would need to be transmitted between the house bank accounts either manually or automatically, with cash concentration requiring transparency on the projected cash position.

The solution may require extra settings in the cash management module with CLS bank accounts to be added to specific groupings.

Conclusion

Designing a CLS solution in SAP requires deep understanding of a client’s treasury operations, bank account structure and SAP TMS specifics. Together with a client and based on the unique business landscape, we review the pros and cons of possible solutions and help choosing the best one. Eventually we can design and implement a solution that makes treasury operations more efficient and transparent.

Our corporate clients are requesting our support with design and implementation of Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS) solutions for FX settlements in their SAP Treasury system. If you are interested, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Analyzing data from a treasury management system and ensuring it is up to date and accurate is key to making effective decisions for any corporate treasurer.

Over recent years, SAP has added an array of products in the data warehousing, reporting and analytics space to assist decision-making as well as address some of the historical weaknesses in its reporting capabilities.

These more recent SAP tools focus on delivering key business drivers in the reporting space – such as agility, flexibility, independence from IT, data processing, intelligent analysis (using artificial intelligence), and data centralization – thereby addressing many of the previous frustrations that business users experienced with getting the necessary information out of their SAP systems to make sound business decisions. Previously, reporting within SAP was often limited, inflexible and required a reliance on IT to develop custom reports and/or data models. But with more options, choosing the most appropriate reporting landscape design can seem overwhelming to the treasury executive and it’s easy to get lost in the technical jargon.

The appropriate tool for your unique business design

When it comes to treasury analytics solutions offered by SAP, there are among others embedded Fiori analytical apps, SAP Analytics Cloud, BW4/HANA and the new Data Warehouse Cloud. It may be difficult to get a clear understanding of what each tool offers and for what purposes to use each. The question then is whether to invest in all tools or which one(s) to choose to meet our reporting needs. Additionally, there may be uncertainty too around what is offered to customers using SAP S/4HANA Cloud versus those customers who run SAP S/4HANA Cloud, private edition (and on premise deployments).

The answer about how to structure your SAP reporting architecture depends on your unique business design and reporting requirements, and more specifically what questions you need answered by your data. Here we will give a brief overview of the functionality of the main tools and what to consider when making system selection decisions. Note, the below information speaks more to customers who run the on-premise version of SAP S/4HANA, although we do mention what is offered on the cloud, where relevant.

SAP S/4HANA Fiori Analytical Apps

SAP S/4HANA Finance for treasury and risk management comes standard with analytical Fiori apps for daily reporting as well as Dashboard reporting. With your daily reporting apps, you will be able to display treasury position flows, analyze the treasury position, use the Cash Flow Analyzer as well as display the treasury posting journal. These apps assist the treasury executive to see the details and results of what has taken place over a given period within the organization. There are also currently four dashboard-type Fiori apps which give an overview of different key areas, namely Foreign Exchange Overview, Interest Rate Overview, Market Data Overview, and Bank Relationship Overview.

Without paying any additional license fees, the above apps give the treasury executive a great starting point with which to review current positions but may not be sufficient to provide the information you want to see and how you want to see it.

SAP Analytics Cloud

SAP Analytics Cloud is SAP’s solution for data visualization, offering business intelligence, planning and predictive analytics in a single solution for all modules, providing a broader, deeper and more flexible analysis of the organization’s operations than the embedded analytical Fiori apps can.

Although the SAP Analytics Cloud OEM version is delivered embedded into Treasury Management for SAP S/4HANA Cloud, customers with the SAP S/4HANA Cloud, private edition, or an on-premise version of Treasury Management will need an additional license to get access to SAP Analytics Cloud functionality. However, it is worth noting that this license is for the full-use SAP Analytics Cloud Enterprise edition, which comes with more features and functionalities than the embedded version.

In terms of Treasury Management, the Treasury Executive Dashboard is the main offering within SAP Analytics Cloud. This dashboard is based on a preconfigured data model that offers real-time insights into the treasury operations across eight tab strips. Areas that can be reported on are Liquidity, Cash management, Bank relationship, Indebtedness, Counterparty risk, Market risk, Bank guarantee and Market overview. The dashboard provides visual overviews of the underlying data and allows for drill-down to see the detail. Customizing the layout is also possible.

With the full-use Enterprise version of SAP Analytics Cloud, there is the possibility of creating more dashboards (called Stories) according to business reporting needs. Business Content is also delivered out the box with the full version which means the creation of new dashboards is accelerated as the groundwork has already been done by SAP or one of their business partners.

Another feature of SAP Analytics Cloud worth mentioning is its predictive capabilities. Historical data is analyzed to identify trends and patterns, and these are then used to predict a potential future outcome, further adding to the tools at the executive’s disposal.

SAP Analytics Cloud is designed to be set up and used by the business user with minimal IT intervention. Dashboards are responsive and user-friendly, with a large degree of flexibility in terms of layout and design.

SAP BW/4HANA

SAP BW/4HANA is SAP’s next generation data warehousing solution designed to run exclusively on the SAP HANA database. The key areas of focus for SAP BW∕4HANA are data modeling, data procurement, analysis and planning. An SAP customer needs to license this product and it runs on a separate instance.

SAP BW/4HANA is not an upgrade of SAP BW but a widely rewritten solution designed to reduce complexity and effort around data warehousing as well as increasing speed and agility, offering advanced UIs.

Data from multiple sources across the enterprise can be imported and stored centrally in the SAP BW∕4HANA Enterprise Data Warehouse. This data can be transformed and cleaned up, ready for analysis. SAP BW/4HANA provides a single source of truth, handling large data volumes at speed for complex organizations. SAP BW/4HANA has been designed to create reports on current, historical, and external data from multiple SAP and non-SAP sources. The data modeling capabilities are also much more powerful than SAP Analytics Cloud offers as a standalone solution.

A note here that SAP has recently released the Data Warehouse Cloud. This is intended as a data warehousing solution for SAP S/4HANA Cloud customers and is not seen as a direct replacement for BW/4HANA. However, the approaches for supporting Self-Service BI, the “SAP BW Bridge capabilities”, or the inclusion of CDS views from SAP S/4HANA make it a good candidate for a hybrid approach at least.

Selecting the right solution

SAP believes that there are four main drivers of the value of data – Span (data from anywhere), Volume (data of any size), Quality (data of any kind) and Usage (data for anyone). They have focused on ensuring that value is maximized for organizations by offering solutions for each driver. The SAP HANA database ensures that a vast volume of data can be handled at high speed, SAP BW/4HANA has been designed so that high volumes of data of any kind can be consolidated for analysis and SAP Analytics Cloud delivers a single solution for visual, easy-to-use analytics across the business.

Customers that have SAP S/4HANA Treasury in their on-premise deployment with minimal data sources could supplement their SAP S/4HANA Treasury system with SAP Analytics Cloud alone. This is ideal when the main reporting needs are operational and real-time and would allow treasury executives to easily access the information they need to optimize their portfolios for liquidity and risk, giving them the additional flexibility and ability to design required reports.

Where the data volumes are large and from a diverse range of sources, a combination of SAP BW4/HANA and SAP Analytics Cloud could be better. The latter has been optimized to work with SAP BW/4HANA as a source and this allows customers to get the powerful, interactive visualizations of SAP Analytics Cloud using the immense data volume capabilities of SAP BW/4HANA. Together, these two products, alongside your SAP S/4HANA Treasury system, give up-to-date, broad, easy-to-read information at a glance to ensure the treasury executive can be proactive and responsive, making the best possible decisions around liquidity, funding and risk management across the entire enterprise. SAP BW4/HANA can of course be implemented without SAP Analytics Cloud, as other BI tools can be used, but the advantages of SAP Analytics Cloud are the highly visual design, flexibility and most importantly not needing to rely on IT to design reports.

To conclude

Knowing what your options are and which would suit your current and future system landscapes is where Zanders can come in, providing sound guidance and ensuring you are able to make the most of any investment to analyze data and make decisions. We can assist treasury executives by ensuring the customer has the right mix of reporting solutions, weighing up total cost of ownership against the data reporting requirements of the organization.

Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS) is an established global system to mitigate settlement risks for FX trades, improving corporate cash and liquidity management among other benefits. The CLS system was established back in 2002 and since then, the FX market has grown significantly. Therefore, there is a high demand from corporates to leverage CLS to improve corporate treasury efficiency.

In this article we shed some light on the possible technical solutions in SAP Treasury to implement CLS in the corporate treasury operations. This includes CLS deal capture, limit utilization implications in Credit risk analyzer, and changes in the correspondence framework of SAP TRM.

Technical solution in SAP Treasury

There is no SAP standard solution for CLS as such. However, SAP standard functionality can be used to cover major parts of the CLS solution. The solution may vary depending on the existing functionality for hedge management/accounting and limit management as well as the technical landscape accounting for SAP version and SWIFT connectivity.

Below is a simplified workflow of CLS deal processing:

The proposed solution may be applicable for a corporate using SAP TRM (ECC to S/4HANA), having Credit risk analyzer activated and using SWIFT connection for connectivity with the banks.

Capturing CLS FX deals

There are a few options on how to register the FX deal as a CLS deal, with two described below:

Option 1: CLS Business partner – a replica of your usual business partner (BP) which would have CLS BIC code and complete settlement instructions.

Option 2: CLS FX product type/transaction type – a replica of normal FX SPOT, FX FORWARD or FX SWAP product type/transaction type.

Each option has pros and cons and may be applied as per a client technical specific.

FX deals trading and capturing may be executed via SAP Trade Platform Integration (TPI), which would improve the processing efficiency, but development may still be required depending on characteristics of the scope of FX dealing. In particular, the currency, product type, counterparty scope and volume of transactions would drive whether additional development is required, or whether standard mapping logic can be used to isolate CLS deals.

For the scenarios where a custom solution is required to convert standard FX deals into CLS FX deals during its creation, a custom program could be created that includes an additional mapping table to help SAP determine CLS eligible deals. The bespoke mapping table could help identify CLS eligibility based on the below characteristics:

- Counterparty

- Currency Pair

- Product Type (Spot, Forward, SWAP)

Correspondence framework

Once CLS deal is captured in SAP TRM, it needs to be counter-confirmed with the trading counterparty and with CLS Bank. Three new types of correspondence need to be configured:

- MT300 with CLS specifics to be used to communicate with the trading counterparty;

- MT304 to communicate with CLS Custody service;

- SWIFT MT396 to get the matching status from CLS bank.

Credit Risk Analyzer (CRA)

FX CLS deals do not bring settlement exposure, thus CLS deals need to be exempt from the settlement risk utilization. Configuration of the limit characteristics must include either business partner number (for CLS Business Partner) or transaction type (for CLS transaction type). This will help determine the limits without FX CLS deals.

No automatic limits creation should be allowed for the respective limit type; this will disable a settlement limit creation based on CLS deal capture in SAP.

CLS Business partner setting must be done with ‘parent <-> subsidiary’ relationship with the regular business partner. This is required to keep a single credit limit utilization and having FX deals being done with two business partners.

Deal execution

Accounting for CLS FX deals is normally the same as for regular FX deals, though it depends on the corporate requirements. We do not see any need for a separate FX unrealized result treatment for CLS deals.

However, settlement of CLS deals is different and standard settlement instructions of CLS deals vary from normal FX deals.

Either the bank’s virtual accounts or separate house bank accounts are opened to settle CLS FX deals.

Since CLS partner performs the net settlement on-behalf of a corporate there is no need to generate payment request for every CLS deal separately. Posting to the bank’s CLS clearing account with cash flow postings (TBB1) is sufficient at this level.

The following day the bank statement will clear the postings on the CLS settlement account on a net basis based on the total amount and posting date.

Cash Management

A liquidity manager needs to know the net result of the CLS deals in advance to replenish the CLS bank account in case the net settlement amount for CLS deal is negative. In addition, the funds would need to be transmitted between the house bank accounts either manually or automatically, with cash concentration requiring transparency on the projected cash position.

The solution may require extra settings in the cash management module with CLS bank accounts to be added to specific groupings.

Conclusion

Designing a CLS solution in SAP requires deep understanding of a client’s treasury operations, bank account structure and SAP TMS specifics. Together with a client and based on the unique business landscape, we review the pros and cons of possible solutions and help choosing the best one. Eventually we can design and implement a solution that makes treasury operations more efficient and transparent.

Our corporate clients are requesting our support with design and implementation of Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS) solutions for FX settlements in their SAP Treasury system. If you are interested, please do not hesitate to contact us.