On 17–19 July 2023, Zanders participated as a proud sponsor at the SAP Treasury conference in Chicago.

As the first conference in the US since its 4-year hiatus, there was good attendance among corporates and partners. The SAP Treasury conference is an excellent opportunity for customers to see the latest developments within the S/4 HANA Treasury suite.

Christian Mnich, VP and Head of Solution Management Treasury and Working Capital Management at SAP, gave the opening keynote titled: "SAP Opening Keynote: Increase Financial Resiliency with SAP Treasury and Working Capital Management Solutions."

Corporate Structure changes

Ronda De Groodt, Applications Integration Architect at Leprino Foods, presented a case study that covered how Leprino Foods embarked on a company-wide migration from SAP ECC to S/4HANA, specifically implementing SAP Treasury, Cash Management, and Payments solutions in a 6-month time frame. The presentation also had a focus on leveraging SAP S/4HANA Cash Management and SAP machine learning capabilities while migrating to S/4 HANA.

Trading Platform Integration

In a joint presentation, Justin Brimfield from ICD and Jonathon Kluding from SAP discussed the strategic partnership between the two companies in developing a streamlined Trading Platform Integration. This presentation went into detail on how SAP leverages Trading Platform Integration between SAP and ICD and the efficiencies this integration can create for Treasury.

Multi-Bank Connectivity (MBC)

Another area of focus at the conference was the capabilities of SAP Multi-Bank Connectivity and how it can simplify and automate financial processes associated while having multiple banks. This was presented by Kweku Biney-Assan from HanesBrands. The presentation focused on answering some crucial questions corporates may have about SAP MBC, ranging from the possible improvements MBC can make to your Treasury Operations and Cash Management processes, to the typical timeline for an implementation.

Cash Management & Liquidity Forecasting

Renee Fan from Freeport LNG, gave a presentation overviewing the challenges the company faced in terms of cash management, reporting, and analytics. She gave an overview of Freeport LNG’s Treasury Transformation Journey and insights into the upgrades they had made, as well as a further focus on the benefits they have seen as a result of their new cash and liquidity solution.

In addition, the conference offered attendees the opportunity to share ideas, build networks, and discuss topics face-to-face. All this made this edition of the event a success!

On 20-22 June 2023, Zanders joined the SAP Treasury conference in Amsterdam as proud sponsor.

Of the many attending corporates and partners were offered the opportunity to hear the latest ins and outs of treasury transformation with S/4HANA.

Next to the enhancements in S/4HANA Treasury, customers had a clear need to understand what it could means for their Treasury and how they could achieve it. The conference provided an excellent opportunity to exchange ideas with each other and learn from the many case studies presented on treasury transformation.

Treasury Transformation with SAP S/4HANA

Alongside Ernst Janssen, Digital Treasury and Banking Manager at dsm-firmenich, Zanders director Deepak Aggarwal presented the value drivers for treasury in an S/4HANA migration. The presentation also included the different target architecture and deployment options, as Ernst talked about the choices made at dsm-firmenich and the rationale behind them in a real-life business case study. Zanders has a long-standing relationship with DSM going back as far as 2001, and has supported them in a number of engagements within SAP treasury.

In addition, there were similar other presentations on treasury transformation with S/4HANA. BioNTech presented the case study on centralization of their bank connectivity via APIs for both inbound and outbound bank communication. They are also the first adopters of the new In-House Bank under Advanced Payment Management (APM) solution and integrate the Morgan Money trading platform for money market funds. ABB and PwC talked about their treasury transformation journey on centralization of cash management in a side-car, functionality enhancement through APM, and integration with Central Finance system for balance sheet FX management. Alter Domus and Deloitte presented their treasury transformation via S/4HANA Public Cloud including integrated market data feed and Multi-Bank Connectivity.

Digital and Streamlined Treasury Management System

Christian Mnich from SAP laid out the vision of SAP Treasury and Working Capital Management solution as an agile, resilient and sustainable solution delivering end-to-end business processes to all customers in all industries. Christian referred to the market challenges of high inflation and rising interest rates calling for a greater need of bank resiliency and cash forecasting to reduce dependencies on business partners and improve cash utilization while avoiding dipping into debt facilities. The sustainability duties like ESG reporting and carbon offsetting appear to be more relevant than ever to meet global assignments. SAP’s 2023 product strategy was presented with Cloud ERP (public or private) at the core, Business Technology Platform as integration and extension layer, and the surrounding SAP and ecosystem applications, delivering end-to-end integrated processes to the business.

Trading Platform Integration

Another focus area was SAP Integration with ICD for Money Market Funds (MMFs) through Trading Platform Integration (TPI) application. MMFs are seen as an attractive alternative to deposits, yielding better returns and diversifying risk through investment in multiple counterparties. Quite often the business is restricted on MMF dealing as a result of system limitations and overhead due to the manual processes. Integration with ICD via TPI offers benefits of single sign on, automated mapping from ICD to SAP Treasury, auto-creation of securities transaction in SAP, email notification and integrated reporting in SAP Treasury.

Embedded Receivables Finance

Lastly, SAP integration with Taulia was another focus area to facilitate liquidity management in the companies. Taulia was presented as driving Working Capital Management (WCM) in the companies through its WCM platform and Taulia Multi Funder for efficient share of wallet or discovery of new liquidity. The embedded receivables finance solution in Taulia automates the receivables sales process by automating the status updates of all invoices in Taulia platform and the seller ERP.

If you are interested in joining SAP Treasury conferences in future, or any of the topics covered, please do reach out to your Zanders’ contacts.

In this article, we will delve deeper into some of the key offerings of SAP BTP for treasury and explore how it can contribute to driving innovation within treasury.

The SAP Business Technology Platform (BTP) is not just a standalone product or a conventional module within SAP's suite of ERP systems; rather, it serves as a strategic platform from SAP, serving as the foundational underpinning for all company-wide innovations. In this article, we will delve deeper into some of the key offerings of SAP BTP for treasury and explore how it can contribute to driving innovation within treasury.

The platform is designed to offer a versatile array of tools and services, aiming to enhance, extend, and seamlessly integrate with your existing SAP systems and other applications. Ultimately enabling a more efficient realization of your business objectives, delivering enhanced operational efficacy and flexibility.

Analytics and AI

One of the standout features of SAP BTP for treasury is its analytics and planning solution, SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC). This feature seamlessly connects with different data sources and other SAP applications. It supports Extended Planning & Analysis and Predictive Planning using machine learning models.

At the core of SAC, various planning areas – like finance, supply chain, and workforce – are combined into a cloud-based interconnected plan. This plan is based on a single version of the truth, bringing planning content together. Enhanced by predictive AI and ML models, the plan achieves more accurate forecasting and supports near-real-time planning. Users can also compare different scenarios and perform what-if analysis to evaluate the impact of changes on the plan equipping organizations to prepare for uncertainties effectively.

Application Development and Integration

An organization's treasury architecture landscape often involves numerous systems, custom applications, and enhancements. However, this complexity can result in challenges related to maintenance, technical debt, and operational efficiency.

Addressing these challenges, SAP BTP offers a solution known as the SAP Build apps tool. The tool enables users to adapt standard functionalities and create custom business applications through intuitive no-code/low-code tools. This allows that all custom development takes place outside your SAP ERP system, thereby preserving a ‘clean core’ of your SAP system. This will allow for a simpler, more streamlined maintenance process and a reduced risk of compatibility issues when upgrading to newer versions of SAP.

In addition, SAP BTP facilitates seamless connectivity through a range of connectors and APIs integrated within the SAP Integration Suite. Enabling a harmonious integration of data and processes across diverse systems and applications, whether they are on-premise or cloud-based.

Process Automation and Workflow Management

Efficient process automation and workflow management play a pivotal role in enhancing treasury operations. SAP BTP offers an efficient solution named SAP Build Process Automation which enables users to design and oversee business processes using either low-code or no-code methods. It combines workflow management, robotic process automation, decision management, process visibility, and AI capabilities, all consolidated within a user-friendly interface.

A significant advantage of SAP BTP's workflow approach over conventional SAP workflows is the unification of workflows across diverse systems, including non-SAP systems and increased flexibility, enabling smoother interaction between processes and systems.

The integration of SAP BTP for workflow with different SAP modules such as TRM, IHC, BAM is facilitated through the SAP Workflow Management APIs within your SAP S/4 HANA system.

In the context of treasury functions, SAP Build Process Automation proves invaluable for automating and refining diverse processes such as cash management, risk management, liquidity planning, payment processing, and reporting. For instance, users can leverage the integrated AI functionalities for tasks like collecting bank statements/account balance information from different systems, consolidating information, saving and/or distributing the cash position information to the appropriate people and systems. Furthermore, the automation recorder can be employed to mechanize the extraction and input of data from diverse systems. Finally, the SAP Build Process Automation can also be utilized to create workflows for complex payment approval scenarios, including exceptions and escalations.

Extensions to the Treasury Ecosystem

SAP BTP extends the treasury ecosystem with multiple treasury-specific developed solutions, seamlessly enhancing your treasury SAP S/4 HANA system functionality. These extensions include: Multi-Bank Connectivity for simplified and secure banking interactions, SAP Digital Payment Add-On for efficiently connecting to payment service providers. Trading Platform Integration for streamlined financial instrument trading, SAP Cloud for Credit Integration to assess business partner credit risk, SAP Taulia for Working Capital Management, Cash Application for automatic bank statement processing and cash application, and lastly, SAP Market Rates Management for the reliable retrieving of market data.

Empowering organizations with extensive treasury needs by enabling them to selectively adopt these value-added capabilities and solutions offered by SAP.

Alternatives to SAP BTP

The primary driving factor to consider integrating SAP BTP as an addon to your SAP ERP is when there is an integrated company-wide approach towards adopting BTP. Furthermore, if the standard SAP functionalities fall short of meeting the specific demands of the treasury department, or if the need for seamless integration with other systems arises.

It's important to prioritize the optimization of complex processes whenever feasible first, avoiding the pitfall of optimizing inherently flawed processes using advanced technologies such as SAP BTP. It is worth noting that the standard SAP functionality, which is already substantial, could very well suffice. Consequently, we recommend conducting an analysis of your processes first, utilizing the Zanders best practices process taxonomy, before deciding on possible technology solutions.

Ultimately, while considering technology options, it's wise to explore offerings from best-of-breed treasury solution providers as well – keeping in mind the potential need for integration with SAP.

Getting Started

The above highlights just a glimpse of SAP BTP's capabilities. SAP offers a free trial that allows users to explore its services. Instead of starting from scratch, you can leverage predefined business content such as intelligent RPA bots, workflow packages, predefined decision and business rules and over 170 open connectors with third-party products to get inspired. Some examples relevant for treasury include integration with Trading Brokers, S4HANA SAP Analytics Cloud, workflows designed for managing free-form payments and credit memos, as well as connectors linking to various accounting systems such as Netsuite Finance, Microsoft Dynamics, and Sage.

Conclusion

SAP BTP for Treasury is a powerful platform that can significantly enhance treasury. Its advanced analytics, app development and integration, and process automation capabilities enable organizations to gain valuable insights, automate tasks, and improve overall efficiency. If you are looking to revolutionize your treasury operations, SAP BTP is a compelling option to consider.

Seamless and automated connectivity between a Treasury Management System (TMS) and banks has always been an arduous task to accomplish.

Treasurers dealing with multiple jurisdictions, scattered banking landscape, and local requirements face many challenges in this regard. Japan is one of the markets where bank connectivity is indeed a challenge, especially when it comes to connecting with local banks.

Traditional options

The initial reaction from treasurers not familiar with local market conventions might be to seek connection through the SWIFT network. However, in Japan only a handful of banks offer SWIFT connectivity. Second natural choice is the Host-to-Host connection (H2H). This is the classic File Transfer Protocol (FTP), or preferably the secured version (sFTP) setup. Some will say old fashioned, rather than classic, since it is as old as the internet. Nonetheless, it is still popular, and frankly quite often the best fit for the purpose. However, if there are dozens of local banks to connect to, it can be difficult to be expected to connect to each of them with a direct H2H. While this could be technically feasible, it would be nothing short of a nightmare to maintain, with the initial setup being time-consuming in the first place.

Other solutions

There is an answer, or should we rather say ANSER, to this question. ANSER, an abbreviation of ‘Automatic answer Network System for Electrical Request’, is a data transfer system provided by NTT Data Corporation since 1981, which links banks with firms.[1] ANSER then is a way to connect a corporate client to the bank. The system has been around for a while, and together with Cash Management Service (CMS) centers it is a part of the so-called Firm Banking solution in Japan. Since its inception, ANSER offered a wider range of services, through which corporates could access their banking information. Among the offered channels are telephone, fax, firm banking terminal, and personal computer. With the ever-increasing need for speedy and accurate information exchange, the more traditional ways, such as telephone and fax, gave way to the more sophisticated and automated solution, namely eBAgent.

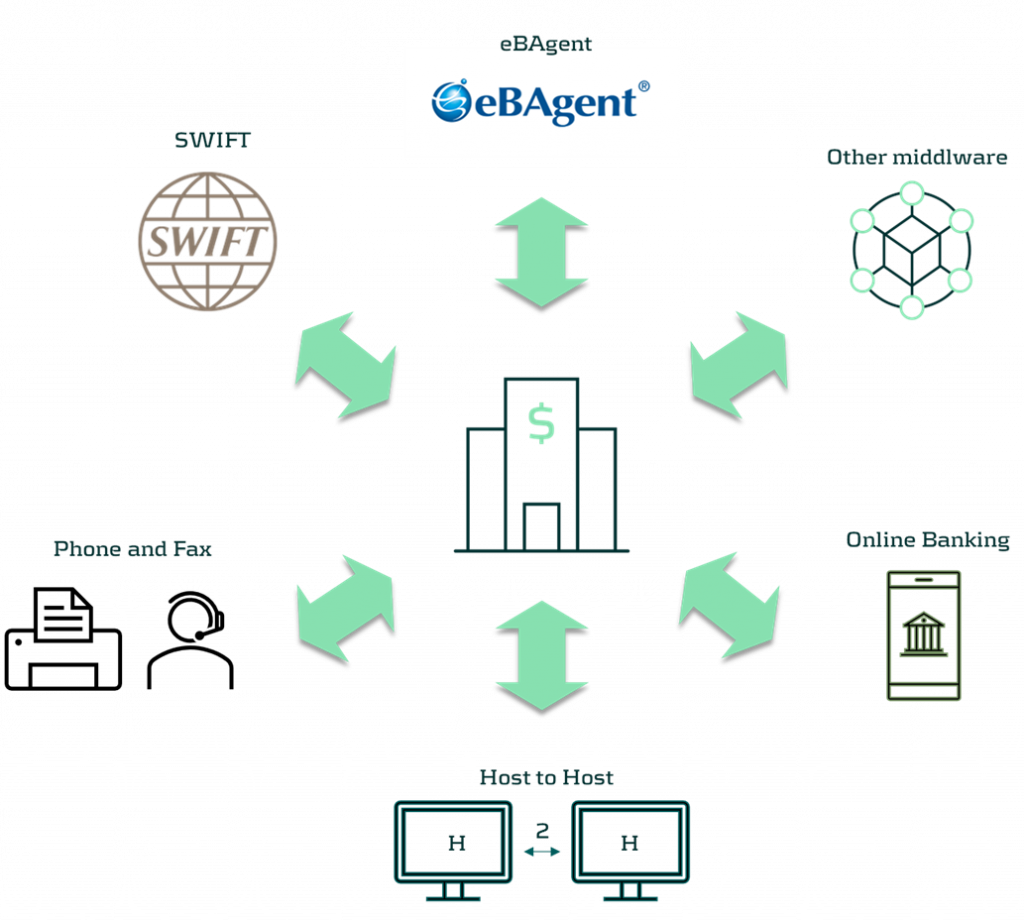

eBAgent making use of API

The said eBAgent is a proprietary middleware platform offered by NTT Data. The solution establishes an automated connection with banks through the above-mentioned ANSER network. In short, eBAgent offers a gateway to multiple local banking partners in Japan utilizing the ANSER network. The remaining part for the corporate is then to establish a connection between the TMS and eBAgent, and secure appropriate contracts with the eBAgent provider, NTT Data, as well as the banks.

As for the connection protocol, the choice is between the classic sFTP, or Application Programming Interface (API). The latter has the real-time advantage, with less lag between the pick-and-drop sFTP connection. API seems to be a choice for an increasing number of corporates these days in this area. What is also interesting, apart from the API connection, are the supported formats for transfers and bank statements. In addition to the local Japanese ZENGIN, the protocol also offers data transmission in a proprietary XML format. This XML format is actually quite simple, with a very limited amount of tags. In addition to this, unlike the ISO 20022 standard, it contains only one level of tags, without the nesting function. Depending on the exact ERP/TMS infrastructure, eBAgent can also provide conversion services from and to the IS 20022 standard. As for the connection to eBAgent, the whole setup seems easier said than done. However, some TMS providers, in response to the demand from the market, started offering off-the-shelf solutions for a plug-and-play connection to eBAgent. Kyriba and Reval already offer it, with SAP set to roll out its solution on the S/4HANA and Multi Bank Connectivity (MBC) platform in early 2024.

Various ways to connect TMS / ERP with banks in Japan

How to connect with local banks in Japan?

It all depends on the exact landscape of banks and systems. It may just as well turn out that a hybrid solution would be best suited. There is no one-size fits all, as each corporate is unique, thus careful consideration and design will be paramount for a stable and reliable connection with banks. One thing is certain, solutions that involve obtaining bank statement information and enact payments by telephone or fax are simply no longer sufficient. In this day and age, when much sensitive information is exchanged between corporates and banks, having a reliable, automated solution is indispensable.

If you would like to know more, do not hesitate to get in touch with Michal Zelazko via [email protected] or via + 81 (0) 8 3255 9966

[1] https://www.boj.or.jp/en/paym/outline/pay_boj/pss0305a.pdf

Due to the changing landscape since the initial inception in 2012, the original EMIR (European Market Infrastructure Regulation) legislation has become outdated.

The EMIR Refit was originally introduced with the goal of simplifying regulations, and these new requirements took effect in 2019. Following the EMIR Refit, there has been a subsequent round of amendments and updated technical guidelines. In this article, we highlight the key changes.

ESMA has published the final reporting guidelines for the updated EMIR refit to take effect on 29 April 2024 (Europe) and 30 September 2024 (UK). These changes, while strivinging to streamline and standardise the reporting across Trade repositories, will add some initial challenges in setting up the new report and reporting format.

Although a significant number of corporates rely on the financial counterparty to report on their behalf, these changes can still cause a major headache for corporates that continue reporting by themselves or need to report internal trades.

Key changes

The first major change concerns the number of fields that can be reported on. Currently there are 129 reportable fields, under the updated legislation there is a withdrawal of 15 and 89 new fields. This brings the new report to a hefty 203 reportable fields.

There will be an introduction of more counterparty-specific fields. These fields will require a deeper understanding of and communication with all counterparties. New counterparty data that will be required includes a Clearing Threshold and Corporate Sector.

The way that these fields will be reported is under huge review. The updated legislation will remove the CSV file, a business staple due to its ease of creation and flexibility, and replace the file with an XML submission using ISO 20022 standards. This move to XML will give corporates the headache of building the necessary XML file. One benefit of the XML format is that it will make moving between Trade Repositories easier as there will be a uniform file specification.

Introducing UPI

Another major change concerns the introduction of a Unique Product Identifier (UPI). The UPI is aimed at reducing the misreporting of products, ISINs, CFI codes, and other classifications. The UPI will be controlled and issued by the Derivatives Service Bureau (DSB). With a central database of identifiers, this should reduce misreporting. It is also hoped that the use of a centrally managed UPI will lead to a reduction in the number of reportable fields in the future . A downside to this change is that companies will need to sign up with the DSB and a fee will be charged for each UPI. There is a general consensus that with the introduction of the UPI, the UTI is likely to be phased out and removed in the future.

One easily missed detail on the new requirements is the necessity to update all outstanding trades to the new reporting format and level of detail, within 6 months of the go-live. This can be problematic for firms that don’t have the necessary data points for the historic trades and will require a review to bring these trades up to the required reporting standard.

In summary, there are large changes in the number of fields needing to be reported, much more granularity required from dealing counterparties, and a change of file type to XML.

Reporting validations and final report can be found on the ESMA website.

With our experience in EMIR and EMIR Refit legislation we can help with the transition to the new reporting requirements.

Please contact Keith Tolfrey or Wilco Noteboom for further insights.

Last year marked a radical change in the status-quo that existed within the financial market, affecting the way banks manage the risks in their banking books.

First and foremost, the long period of low and even negative swap rates was followed by strongly rising rates and a volatile market, which impacted the behavior of both customers and banks themselves. At the same time, regulatory developments, initiated by EBA’s new IRRBB guidelines, have shifted the banks’ focus to managing their earnings and earnings risk, rather than economic value risks.

Non-maturing deposits (NMDs) are of particular interest in this respect, given the uncertainty regarding the future pricing strategy and volume developments involved in these products. Moreover, as NMDs are generally modeled with a rather short maturity, the portfolio plays a significant role in the stability of the NII, making this portfolio even more relevant to evaluate in light of the newly introduced Supervisory Outlier Test (SOT) limits on earnings risk (more specific NII), or the local equivalent.

How does this affect IRRBB management at banks?

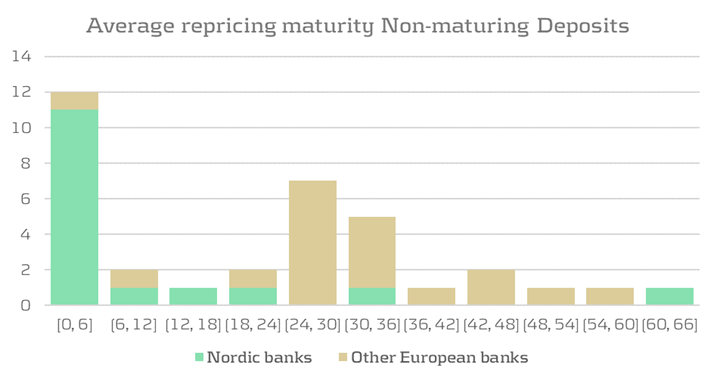

The exact impact of these developments is also heavily dependent on the bank’s local market, and corresponding laws and regulation, as well as the balance sheet composition of the bank. In Nordics countries, banks are affected more heavily, given that loans and mortgages generally have shorter maturities, as compared to other Western European countries like Germany and the Netherlands. This yields a smaller maturity mismatch with on-demand deposits at the liability side, such that a natural hedge exists to some extent within the balance sheet. Earlier on, this effect, combined with the rather stable markets, made active ALM, including IRRBB management, less urgent. The incentive to accurately model NMDs was therefore limited, so most banks simply replicate this funding overnight, while banks in other European countries tend to use a longer maturity, as illustrated by figure 1.

{Figure 1: Difference in average repricing maturity of NMDs between Nordic banks and other European banks, based on Pillar 3 IRRBBA and IRRBB1 disclosures from 2022 annual reports}

While the natural hedge already (partially) mitigates the risks from a value perspective to a large extent, investing the full NMDs portfolio overnight leads to relatively high NII volatility, thereby potentially violating regulatory limitations. The return on overnight investments will directly reflect any changes in the market rates, while deposit rates in reality are usually somewhat slower to include such developments. Although the resulting asymmetry between the investment return and deposit rate to be paid to customers yields a positive result under rising interest rates, it can reduce profits when interest rates start to fall.

Historically, banks in the Nordics experienced less flexibility in the modeling of NMDs, due to regulatory guidelines being somewhat stricter than EBA guidelines. For instance, Sweden’s Finansinspektionen (FI) required banks to replicate these positions overnight. However, relatively recently, the FI updated its regulations (FI dnr 19-4434), allowing banks to somewhat extend the duration of the investment profile, for a limited portion of the portfolio, and up to a maturity of one year. This results in flexibility to update the investment profile to better reflect the expected repricing speed of deposit rates, which could lead to improved NII stability. Additionally, besides applying these revised NMD models for managing banking book risks, they can, when approved, also be used for effective and consistent capital charge calculations under Pillar 2.

How can these developments be properly managed?

Even though the recent market developments create additional challenges in IRRBB management for banks, they also provide opportunities. The margin on deposit products for banks is currently improving, since only part of the interest rate rises is passed through to customers. The increased interest rates also mean that more advanced NMD models, with longer maturity profiles, can have a positive impact on the P&L, while simultaneously improving the interest rate risk management.

In such a rare win-win situation, it is more advantageous than ever to prioritize NMD modeling. In reassessing the interest rate risk management approach towards NMDs, banks should explicitly balance the tradeoff between value and earnings stability when making conceptual choices. These conceptual choices should align with the overall IRBBB strategy, as well as the intended use of the model, to ensure the risk in the portfolio is properly managed.

In weighing these conceptual alternatives, it is essential to take portfolio-specific characteristics into account. This requires an analysis of historical behavior, and an interpretation of how representative this information is. If behavior is expected to change, a common approach is to supplement historical data with expert expectations of forward-looking scenarios to develop a model that reflects both. Periodically reassessing the conceptual choices ensures a proper model lifecycle of NMD portfolios. This is crucial for accurate measurement of interest rate risk as well as for staying competitive in the current market environment.

Would you like to hear more? Contact Bas van Oers for questions on developing a non-maturing deposit model.

On Thursday 15 June 2023, Zanders hosted a roundtable on ‘Climate Scenario Design & Stress Testing’. This article discusses our view on the topic and highlights key insights from the roundtable.

On Thursday 15 June 2023, Zanders hosted a roundtable on ‘Climate Scenario Design & Stress Testing’. In our head office in Utrecht, we welcomed risk managers from several Dutch banks. This article discusses our view on the topic and highlights key insights from the roundtable.

In recent years, many banks took their first steps in the integration of climate and environmental (C&E) risks into their risk management frameworks. The initial work on climate-related risk modeling often took the form of scenario analysis and stress testing. For example, as part of the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) or by participating in the 2022 Climate Stress Test by the European Central Bank (ECB). To comply with the ECB’s expectations on C&E risks, banks are actively exploring methodologies and data sources for adequate climate scenario design and stress testing. The ECB requires that banks will meet their expectations on this topic by 31 December 2024.

Our view

We believe that banks should start early with climate stress testing, but in a manageable and pragmatic way. Banks can then improve their methodologies and extend their scope over time. This allows for a gradual development of knowledge, data and methodologies within all relevant Risk teams. Zanders has identified the following steps in the process of climate scenario design and stress testing:

- Step 1: Scenario selection

A bank has to select appropriate (climate) scenarios based on the bank’s climate risk materiality assessment. Important to consider in this phase is the purpose for which the scenarios will be used, whether the scenarios are in line with scientific pathways, and whether they account for different policy outcomes (like an early or late transition to a sustainable economy).

- Step 2: Scope and variable definition

An appropriate scope must then be selected and appropriate variables defined. For example, banks need to determine which portfolios to take in scope, which time horizons to include, select the granularity of the output, the right level of stress, and which climate- and macro-economic variables to consider.

- Step 3: Methodology

Then, the bank needs to develop methodologies to calculate the impact of the scenarios. There are no one-size-fits-all approaches and often a combination of different qualitative and quantitative methodologies is needed. We recommend that the climate stress test approach be initially simple and to focus on material exposures.

- Step 4: Results

It is important to use the results of the scenario analysis in the relevant risk and business processes. The results can be used for the bank’s risk appetite and strategy. The results can also help to create awareness and understanding among internal stakeholders, and support external disclosures and compliance.

- Step 5: Stress testing framework

Finally, banks should establish minimum standards for climate scenario design and stress testing. This framework should include, amongst others, policies and processes for data collection from different sources, how adequate knowledge and resources are ensured, and how the scenarios are kept up-to-date with the latest market developments.

Key insights

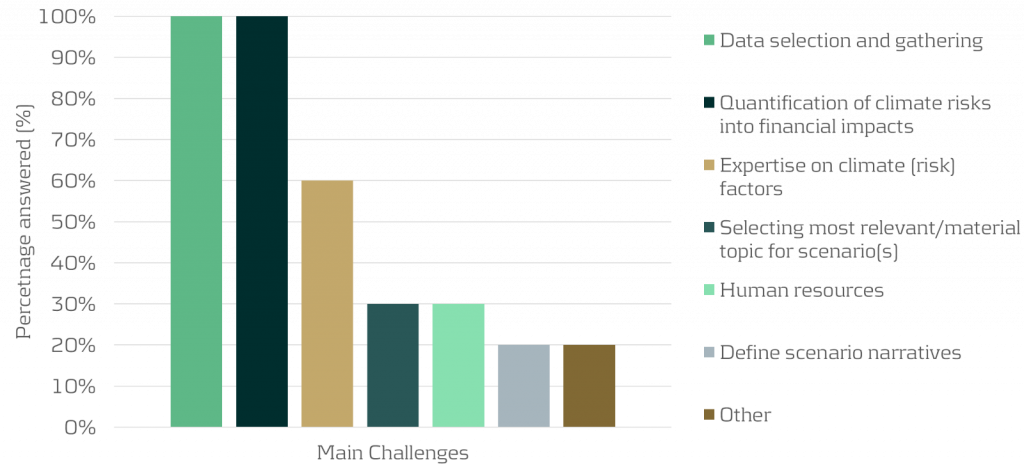

Prior to the roundtable, participants filled in a survey related to the progress, scope and challenges on climate risk stress testing. The key insights presented below are based on the results of this survey, together with the outcomes of the discussion thereafter.

The financial sector has advanced with several aspects around integrating climate risks in risk management over the past year. This was recognized by all participants, as they had all performed some form of climate risk stress testing. The scope of the stress testing, however, was relatively limited in some cases. For example, all participants considered credit risk in their climate risk scenario with many also including market risk. Only a limited number of participants took other risk types into account.

Furthermore, all participants assessed the short-term impact (up to 3 years) of the climate scenarios, whereas only around 40% and 10% assessed the impact on the medium term (3 to 10 years) and long term (>10 years), respectively. This is probably related to the fact that all participants used climate scenarios in their ICAAP, which typically covers a three-year horizon. The second most mentioned use for the climate scenarios, after the ICAAP, was the risk identification & materiality analysis. A smaller percentage of participants also used the climate scenarios for business strategy setting, ILAAP and portfolio management.

The two topics that were unanimously mentioned as the main challenges in climate risk stress testing are data selection and gathering, and the quantification of climate risks into financial impacts, as shown in the graph below:

- Insight 1: Assessing impact of climate risk beyond the short-term very much increases the complexity and uncertainty of the exercise

The participants indicated that climate stress testing beyond the short-term horizon (beyond 3 to 5 years) is very difficult. Beyond that horizon, the complexity of the (climate) scenarios increases materially due to uncertainties of clients’ transition plans, the bank’s own transition plan and climate strategy (e.g., related to pricing and client acceptance policies), and climate policies and actions from governments and regulators. Taking the transition plans of clients into account on a granular level is especially difficult when there is a large number of counterparties. There are no clear solutions to this. Some ideas that take longer-term effects into account were floated, such as adjusting the current valuation of various assets by translating future climate impact on assets into a net present value of impact or by taking climate impacts into account in the long-term macro-economic scenarios of IFRS9 models.

- Insight 2: Whether to use a top-down or bottom-up approach depends on the circumstances

It was discussed whether a bottom-up stress test for climate scenarios is preferable to a top-down stress test. The consensus was that this depends on the circumstances, for example:- Physical risks are asset- and location-specific; one street may flood but not the next. So, in that case a bottom-up assessment may be necessary for a more granular approach. On the other hand, for transition risks, less granularity might be sufficient as transition policies are defined on national or even supranational level, and trends and developments often materialize on sector-level. In those cases, a top-down type of analysis could be sufficient.

- If the climate stress test is used to get a general overview of where risks are concentrated, a top-down analysis may be appropriate. However, if it is used to steer clients, a more granular, bottom-up approach may be needed.

- A bottom-up approach could also be more suitable for longer-term scenarios as it allows to include counterparty-specific transition plans. For more short-term scenarios, a sector average may be sufficient, considering that there will be less transition during this period.

- Insight 3: Translating the results of climate risk stress testing into concrete actions is challenging

The results of the stress test can be used to further integrate climate risk into risk management processes such as materiality assessment, risk appetite, pricing, and client acceptance. Most participants, however, were still hesitant to link any binding actions to the results, such as setting risk limits (e.g., limiting exposures to a certain sector), adjusting client acceptance, or amending pricing policies. However, the ECB does require banks to consider climate impacts in these processes. The most mentioned uses of the climate risk stress testing results were risk identification & materiality assessments and risk monitoring.

Conclusion

Most banks have taken first steps in relation to climate scenario design and stress testing. However, many challenges still remain, for example around data selection and quantification methodologies. Efforts by banks, regulators and the market in general are required to overcome these challenges.

Zanders has already supported several banks with climate scenario design and stress testing. This includes the creation of a climate scenario design framework, the definition of climate scenarios, and by quantifying climate risk impacts for the ICAAP. Next to that, we have performed research on modeling approaches that can be used to quantify the impact of transition and physical risks. If you are interested to know how we can help your organization with this, please reach out to Marije Wiersma.

At the end of July, the European Banking Authority (EBA) released the results on the latest installment of the EU-wide stress test that is performed every two years.

Seventy banks have been considered, which is an increase of twenty banks compared to the previous exercise. The portfolios of the participating banks contain around three quarters of all EU banking assets (Euro and non-Euro).

Interested in how the four Dutch banks participating in this EBA stress test exercise performed? In this short note we compare them with the EU average as represented in the results published [1].

General comments

The general conclusion from the EU wide stress test results is that EU banks seem sufficiently capitalized. We quote the main 5 points as highlighted in the EBA press release [1]:

- The results of the 2023 EU-wide stress test show that European banks remain resilient under an adverse scenario which combines a severe EU and global recession, increasing interest rates and higher credit spreads.

- This resilience of EU banks partly reflects a solid capital position at the start of the exercise, with an average fully-loaded CET1 ratio of 15% which allows banks to withstand the capital depletion under the adverse scenario.

- The capital depletion under the adverse stress test scenario is 459 bps, resulting in a fully loaded CET1 ratio at the end of the scenario of 10.4%. Higher earnings and better asset quality at the beginning of the 2023 both help moderate capital depletion under the adverse scenario.

- Despite combined losses of EUR 496bn, EU banks remain sufficiently apitalized to continue to support the economy also in times of severe stress.

- The high current level of macroeconomic uncertainty shows however the importance of remaining vigilant and that both supervisors and banks should be prepared for a possible worsening of economic conditions.

For further details we refer to the full EBA report [1].

Dutch banks

Making the case for transparency across the banking sector, the EBA has released a detailed breakdown of relevant figures for each individual bank. We use some of this data to gain further insight into the performance of the main Dutch banks versus the EU average.

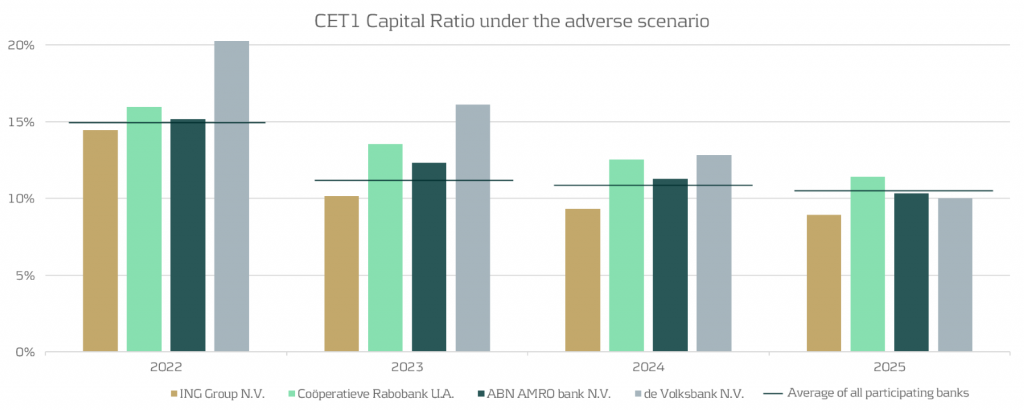

CET1 ratios

Using the data presented by EBA [2], we display the evolution of the fully loaded CET1 ratio for the four banks versus the average over all EU banks in the figure below. The four Dutch banks are: ING, Rabobank, ABN AMRO and de Volksbank, ordered by size.

From the figure, we observe the following:

- Compared to the average EU-wide CET1 ratio (indicated by the horizontal lines in the graph above), it can be observed that three out of four of the banks are very close to the EU average.

- For the average EU wide CET1 ratio we observe a significant drop from year 1 to year 2, while for the Dutch banks the impact of the stress is more spread out over the full scenario horizon.

- The impact after year 4 of the stress horizon is more severe than the EU average for three out of four of the Dutch banks.

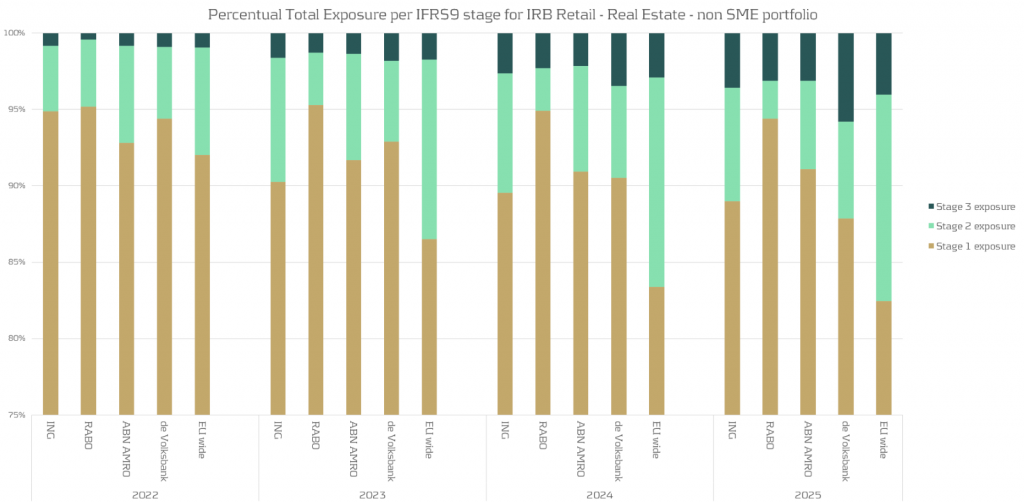

Evolution of retail mortgages during adverse scenario

The most important product the four Dutch banks have in common are the retail mortgages. We look at the evolution of the retail mortgage portfolios of the Dutch banks compared to the EU average. Using EBA data provided [2], we summarize this in the following chart:

Based on the analysis above , we observe:

- There is a noticeable variation between the banks regarding the migrations between the IFRS stages.

- Compared to the EU average there are much less mortgages with a significant increase in credit risk (migrations to IFRS stage 2) for the Dutch banks. For some banks the percentage of loans in stage 2 is stable or even decreases.

Conclusion

This short note gives some indication of specifics of the 2023 EBA stress applied to the four main Dutch banks.

Should you wish to go deeper into this subject, Zanders has both the expertise and track record to assist financial organisations with all aspects of stress testing. Please get in touch.

References

We are excited to announce that Zanders has been listed on the Swift Customer Security Programme (CSP) Assessment Providers directory*.

The CSP helps reinforce the controls protecting participants from cyberattack and ensures their effectivity and that they adhere to the current Swift security requirements.

*Swift does not certify, warrant, endorse or recommend any service provider listed in its directory and Swift customers are not required to use providers listed in the directory.

Swift Customer Security Programme

A new attestation must be submitted at least once a year between July and December, and also any time a change in architecture or compliance status occurs. Customer attestation and independent assessment of the CSCF v2023 version is now open and valid until 31 December 2023. July 2023 also marks the release of Swifts CSCF v2024 for early consultation, which is valid until 31 December 2024.

Swift introduced the Customer Security Programme to promote cybersecurity amongst its customers with the core component of the CSP being the Customer Security Controls Framework (CSCF). Independent assessment has been introduced as a prerequisite for attestation to enhance the integrity, consistency, and accuracy of attestations. Each year, Swift releases an updated version of the CSCF that needs to be attested to with support of an independent assessment.

The Attestation is a declaration of compliance with the Swift Customer Security Controls Policy and is submitted via the Swift KYC-SA tool. Dependent on the Swift Architecture used, the number of controls to be implemented vary; of which certain are mandatory, and others advisory.

Further details on the Swift CSCF can be found on their website:

- https://www.swift.com/myswift/customer-security-programme-csp

- https://www.swift.com/myswift/customer-security-programme-csp/find-external-support/directory-csp-assessment-providers

Our services

Do you have arrangements in place to complete the independent assessment required to support the attestation?

Zanders has experience with and can support the completion of an independent external assessment of your compliance to the Swift Customer Security Control Framework that can then be used to fully complete and sign-off the Swift attestation for this year.

With an extensive track record of designing and deploying bank integrations, our intricate knowledge of treasury systems across both IT architecture as well as business processes positions us well to be a trusted independent assessor. We draw on past projects and assessments to ask the right questions during the assessment phase, aligning our customers with the framework provided by Swift.

The Swift attestation can also form part of a wider initiative to further optimise your banking landscape, whether that be increasing the use of Swift within your organisation, bank rationalization or improving your existing processes. The availability of your published attestation and its possible consultation with counterparties (upon request) helps equally in performing day-to-day risk management.

Approach

Planning

We start with rigorous planning of the assessment project, developing a scope of work and planning resources accordingly. Our team of experts will work with clients to formulate an Impact Assessment based on the most recent version of the Swift Customer Security Controls Framework.

Architecture Classification

A key part of our support will be working with the client to formulate a comprehensive overview of the system architecture and identify the applicable controls dictated by the CSCF.

Perform Assessment

Using our wide-ranging experience, we will test the individual controls against specific scenarios designed to root out any weaknesses and document evidence of their compliance or where they can be improved.

Independent Assessment Report

Based on the evidence collected, we will prepare an Independent Assessment report which includes status of the compliance against individual controls, baselining them against the CSCF and recommendations for improvement areas within the system architecture.

Post Assessment Activities

Once completed, the Independent Assessment report will support you with the submission of the Attestation in line with the requirements of the CSCF version in force, which is required annually by Swift. In tandem, Zanders can deliver a plan for implementation of the recommendations within the report to ensure compliance with current and future years’ attestations. Swift expects controls compliance annually, together with the submission of the attestation by 31 December at the latest, in order to avoid being reported to your supervisor. Non-compliant status is visible to your counterparties.

Do you need support with your Swift CSP Independent Assessment?

We are thrilled to offer a Swift CSP Independent Assessment service and look forward to supporting our clients with their attestations, continuing their commitment to protecting the integrity of the Swift network, and in doing so supporting their businesses too. If you are interested in learning more about our services, please contact us directly below.

Get performance now

- Contact me

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from HubSpot. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information

Even though machine learning is rapidly transforming the financial risk landscape, it is underused within internal ratings based-models. Why is it uncommon within this field, how will this change in the near future, and who will take the lead?

Machine learning (ML) models have proven to be highly effective in the field of credit risk,

outperforming traditional regression models in their predictive power. Thanks to the exponential growth in the data availability, storage capacity and computational power, these models can be effectively trained on vast amounts of complex, unstructured data.

Despite these advantages, however, ML models have yet to be integrated into internal rating-based (IRB) modeling methodologies used by banks. This is mainly due to the fact that existing methods for calculating regulatory capital have remained largely unchanged for over 15 years, and the complexity of ML models can make it difficult to comply with the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). Nonetheless, the European Banking Authority (EBA) recognizes the potential of ML in the future of IRB modeling and is considering providing a set of principle-based recommendations to ensure its appropriate use.

In sight of these recommendations, the EBA published a discussion paper (EBA/DP/2021/04) to seek stakeholders’ feedback on the practical use of ML in the context of IRB modeling, aiming to provide clarity on supervisory expectations. This paper outlines the challenges and opportunities in using ML to develop CRR-compliant IRB models, and presents the point of view for various banking stakeholders on the topic.

Current use and potential benefits of ML in IRB models

According to research conducted by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) in 2019, the most

common uses of ML within credit risk are credit approval, credit monitoring and collections, and

restructuring and recovery. However, the use of ML within other regulatory areas, such as capital

requirements, stress testing and provisioning is highly limited. For IRB models, ML is used to

complement standard models used for capital requirement calculation. Examples of current uses of ML to complement standard models include (i) model validation, where the ML model serves as a challenger model, (ii) data improvements, where ML is used for more efficient data preparation and exploration, and (iii) variable selection, where ML is used to detect explanatory variables.

ML has the potential to provide a range of benefits for risk differentiation, including improvements in the model discriminatory power 1 , identification of relevant risk drivers 2 , and optimization of the portfolio segmentation. Based on their superior predictive ability and capacity to detect bias , ML models can also help to improve risk quantification 3 . Furthermore, ML can be used to enhance the data collection and preparation process, leading to improved data quality. Finally, ML models can enable the use of unstructured data, expanding the possible data sets allowing for the use of new parameters and estimation of these parameters.

Challenges to CRR compliance

The following table summarizes the challenges involved in using ML to develop IRB models that are compliant to prudential requirements.

| Area | Topic | Article ref. | Challenge |

| Risk differentiation | The definition and assignment criteria to grades or pools | CRR 171(1)(a) and (b) RTS on AM for IRB 24(1) | Use of ML is constrained when no clear economic relation between the input and the output variables. Institutions should explore suitable tools to interpret complex ML models. |

| Risk differentiation | Complementing human judgement | CRR 172(3) and 174(e) GL on PD and LGD 58 | Complexity in ML models may make it more difficult to take into account expert involvement and analyze the impact of human judgement on the performance of the model. |

| Risk differentiation | Documentation of modeling assumptions and theory behind the model | CRR 175(1) and (2), 175(4)(a) RTS on AM for IRB 41(d) | To document a clear outline of the theory, assumptions and mathematical basis of the final assignment of estimates to grades, exposures or pools may be difficult in complex ML models. Also, the institution’s relevant staff should fully understand the model’s capabilities and limitations. |

| Risk quantification | Plausibility and intuitiveness of the estimates | CRR 179(1)(a) | ML models can result in non-intuitive estimates, particularly when the structure of the model is not easily interpretable. |

| Risk quantification | Underlying historical observation period | CRR 180(1)(a) and (h), 180(2)(a) and (e), and 181(1)(j) and 181(2). | For PD and LGD estimation, the minimum length of the historical observation period is five years. This can be a challenge for the use of big data, which might not be available for a sufficient time horizon. |

| Validation | Interpreting and resolving validation findings | CRR 185(b) | Difficulties may arise in ML models in explaining material differences between the realized default rates and the expected range of variability of the PD estimates per grade. This also holds for assessing the effect of the economic cycle on the logic of the model. |

| Validation | Validation tasks | CRR 185 | It may be more difficult to assess the representativeness and to fulfill operational data requirements (e.g. data quality and maintenance). Furthermore, the validation function is expected to challenge the model design, assumptions and methodology, whereas a more complex model will be harder to challenge efficiently. |

| Governance | Corporate governance | CRR 189 | The institution’s management body is required to possess a general understanding of the rating systems of the institution and detailed comprehension of the associated management reports. |

| Operational | Implementation process | CRR 144, 171 RTS on AM for IRB 11(2)(b) | The complexity of ML models may make it more difficult to verify the correct implementation of internal ratings and risk parameters in IT systems. In particular, the heavy utilization of different packages will become challenging. |

| Operational | Categorization of model changes | CRR 143(3) | If models are updated at a high frequency with time-varying weights associated to variables, it may be difficult to categorize the model changes. For the validation function it is unfeasible to validate each model iteration. |

Expectations for a possible and prudent use of ML in IRB modeling

In January 2020, the EBA published a report on the recent trends of big data and advanced analytics (BD&AA) in the banking sector. In order to support ongoing technological neutrality – the freedom to choose the most appropriate technology adequate to their needs and requirements - the BD&AA report recommends the use of ML and suggests safeguards to ensure compliance. Meanwhile, the EBA has provided the following principles to clarify how to adhere to the regulatory requirements set out in the CRR for IRB models.

- All relevant stakeholders should have an appropriate level of knowledge of the model’s functioning. This includes the model development unit, credit risk control unit and validation unit, but also the management body and senior management, to a lesser extent.

- Zanders believes that appropriate trainings on the use of ML to the relevant stakeholders ensures the appropriate level of knowledge.

- Institutions should avoid unnecessary complexity in the modeling approach if it is not justified by a significant improvement in the predictive capabilities.

- Zanders advocates to focus on the use of explanatory drivers with significant predictive information to avoid including an excessive number of drivers. In addition, Zanders advises on which data type (unstructured or more conventional) and what modeling choice (simplistic or sophisticated) is appropriate for the institution to avoid unnecessary complexity.

- Institutions should ensure that the model is correctly interpreted and understood by relevant stakeholders.

- Zanders assesses the relationship of each single risk driver with the output variable, ceteris paribus, the weight of each risk driver to detect the level of influence on the model prediction, the economic relationship to ensure plausible and intuitive estimates, and the potential biases in the model, such that the model is correctly interpreted and understood.

- The application of human judgement in the development of the model and in performing overrides should be understood in terms of economic meaning, model logic, and model behavior.

- Zanders provides best market practice expertise in applying human judgement in the development and application of the model.

- The parameters of the model should generally be stable. Therefore, institutions should perform sensitivity analysis and identify/monitor reasons for regular updates.

- Zanders analyses whether a break in the economic conditions or in the institution’s processes or in the underlying data might justify a model update. Furthermore, Zanders evaluates the changes required to obtain stable parameters over a longer time horizon.

- Institutions should have a reliable validation, which covers overfitting issues, challenging the model design, reviewing representativeness and data quality issues, and analyzing the stability of estimates.

- Zanders provides validation activities following regulatory compliance.

Survey responses

The following stakeholders provided responses to the questions posed in the EBA paper (EBA/DP/2021/04):

- Asociación Española de Banca (AEB) – Spanish Banking Association

- Assilea – Italian Leasing Association

- Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME)

- European Association of Co-operative Banks (EACB)

- European Savings and Retail Banking Group (ESBG)

- Fédération Bancaire Française - French Banking Federation (FBF)

- Die deutsche Kreditwirtschaft – The German Banking Industry Committee (GBIC)

- Institute of International Finance (IIF)

- Mazars – audit, tax and advisory firm

- Prometeia SpA – advisory and tech solutions firm (SpA)

- Banca Intesa Sanpaolo – Italian international banking group (IIBG)

A summary of the responses to key questions is provided below.

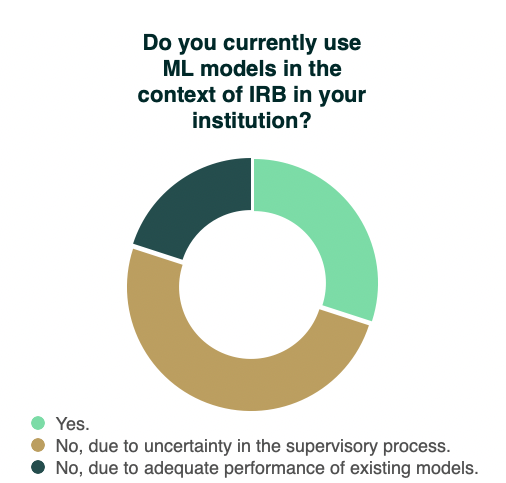

The vast majority of respondents does not currently apply ML for IRB purposes. The respondents argue that they would like to use ML for regulatory capital modeling, but that this is not deemed feasible without explicit regulatory guidelines and certainty in the supervisory process. AEB refers to the report published by the Bank of Spain in February 2021, where it was concluded that ML models perform better than traditional models in estimating the default rate, and that the potential economic benefits would be significant for financial institutions. AECB and GBIC indicate that the need for ML in regulatory capital modeling is currently not necessary as the predictive power of traditional models prove to be satisfactory. Three respondents presently use ML to some extent within IRB, such as for risk driver selection and risk differentiation. Only IIBG has actually developed a complete ML model for the estimation of PD of an SME retail portfolio, which has been validated by the supervisor in 2021.

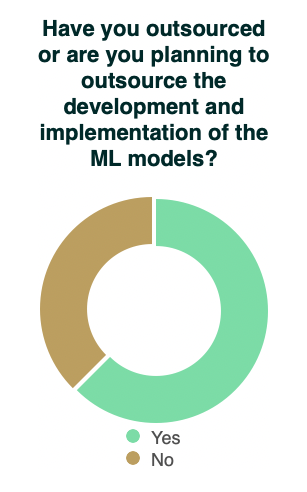

Five respondents answer that they would outsource the ML modeling for IRB to different degrees. AEB states that most of the work will be done internally and consulting services will be required at peak planning times. According to Mazars, the outsourcing is mainly performed on the development phase as banks would take over the ownership of the model and implement it in its IT infrastructure internally. The other respondents that plan to outsource foresee that external support is required for all phases. The remaining respondents state that they have not noticed any intention to outsource any of the parts or phases of the process on the development and implementation of the ML models.

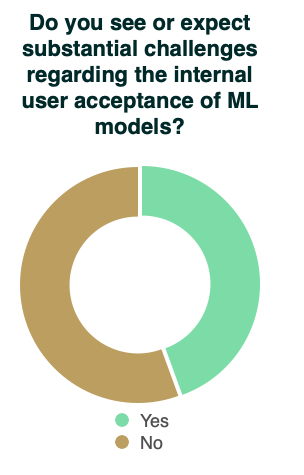

The respondents are split almost evenly on the topic of challenges regarding internal user acceptance of ML models. The respondents that see substantial challenges attribute this to the low explanatory power of ML-driven models and concerns on business representatives and credit officers being comfortable with the understanding and interactions of the standard approaches. However, for the latter it is recognized that specific trainings on ML methods are beneficial in this respect. The respondents that do not expect considerable challenges argue that ML models should be treated in the same manner as traditional methods as the same fundamental principles apply, where it is key to ensure that all Lines of Defense have the appropriate skills and responsibilities. Furthermore, the respondents state that existing ML applications, such as in AML, can be leveraged. The AFM explains that the techniques used to explain the results that are already available in those contexts are proving to be effective to understand the outcomes. SpA shares this sentiment and refers to Shapley values and the Lime test as techniques for model interpretability.

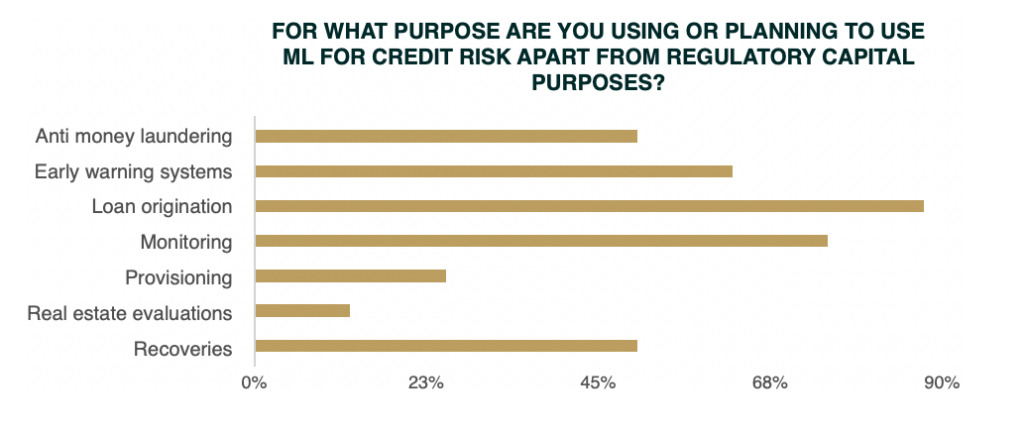

There exists a consensus among the respondents that ML is suitable for various areas within credit risk. For example, ESBG outlines that the opportunities for using ML models within the credit risk area and their advantages are endless. In particular for loan origination (admission), monitoring and early warning systems, the respondents are mutually in favor of applying ML. In general, the application of ML for these purposes is already being adopted by institutions far more than for IRB modeling.

To conclude

Banks are keen to use ML in the context of IRB modeling given the benefits achievable in both risk differentiation and risk quantification processes. The main reason for the limited use of ML in IRB modeling is the uncertainty in the supervisory process. The ball is currently in EBA’s court. The discussion paper and prospective set of principle-based recommendations to bridge the gap in institutional and regulatory expectations show EBA’s interest in making ML in IRB modeling a more common reality.

Zanders believes that institutions are best prepared for this transition by already applying ML to different fields, such as AML, application models and KYC. The EBA defines the enhancement of capacity to combat money laundering in the EU as one of its five main priorities for 2023 (EBA/REP/2022/20). This includes supporting the implementation of robust approaches to advance AML. Zanders anticipates that the technical EBA support in AML will spill over to IRB modeling in the coming three years. Zanders supports institutions in the application of ML in aforementioned fields, which will ensure that those institutions are adequately prepared to fully reap the rewards when ML in the context of IRB modeling is commonly accepted.

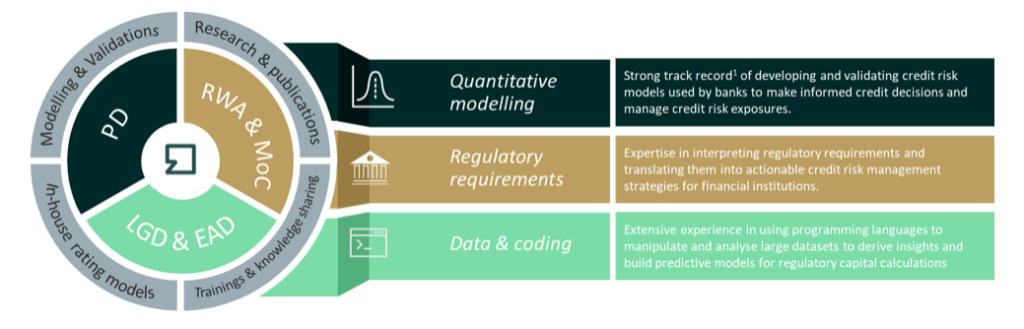

What can Zanders offer?

We combine deep credit risk modeling expertise with relevant experience in regulation and programming

- A Risk Advisory Team consisting of 70+ consultants with quantitative backgrounds (e.g., Econometrics and Physics)

- Strong knowledge of credit risk models

- Extensive experience with calibration and implementation of credit risk models

- We offer ready-to-use rating models, Credit Risk Academy modules and expert sessions that can be tailored to you specific needs.

Interested in ML in credit risk, Credit Risk Academy, and other regulatory capital modeling services? Please feel free to contact Jimmy Tang or Elena Paniagua-Avila.

Footnotes

1 CRR article 170(1)(f) and (3)(c), and RTS on AM of IRB articles 36(1)(a) and 37(1)(c)

2 CRR articles 170(3)(a) and (4) and 171(2) and GL on PD and LGD paragraphs 21, 25, and 121

3 RTS on AM of IRB articles 36(1)(a) and 37(1)(c)