SAP Analytics Cloud – Liquidity Planning in SAC

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

While SAC is a planning tool to be considered, it requires further exploration to evaluate its fit with business requirements and how it could unlock opportunities to potentially streamline the CFF process across the organization. For the organizations already using SAP BPC (Business Process & Consolidation) for planning, SAC could be seen as another ‘kid on the block’. It is important for them to have a clear business case for SAC.

In this article, we introduce SAC liquidity planning solution focusing on its integrated and predictive planning capabilities. We explain the concerns of corporate treasuries that have invested heavily in SAP BPC (either as standalone instance or embedded on S/4 HANA) and discuss the business case for SAC under different scenarios of extending the BPC planning solution to SAC.

What is SAC?

SAC is the analytics and planning solution within SAP Business Technology Platform which brings together analytics and planning with unique integration to SAP applications and smooth access to heterogeneous data sources.

Among the key benefits of SAC are Extended Planning & Analysis (xP&A) and Predictive Planning based on machine learning models. While xP&A integrates (traditional) financial and operational planning resulting in one connected plan that also meets the needs of operational departments, predictive planning augments decision making through embedded AI & ML capabilities.

Extended Planning & Analysis (xP&A)

Historically, the corporate planning has been typically biased towards finance and it was quite inadequate for operational departments who have to resort to local planning in silos for their own decision making. The xP&A approach goes beyond finance and integrates strategic, financial and operational planning in one connected plan. Planning under xP&A also moves beyond budgeting and rolling forecasts to a more agile and collaborative planning process which is near real-time with faster reaction times.

SAC can be seen as the technology enabler for xP&A, as follows:

- It brings together financial, supply chain, and workforce planning in one connected plan deployed in the cloud;

- Unified planning content with a single version of the truth that everyone is working on (plans are fit for purpose for the individual departments and at the same time integrated into one connected plan);

- Predictive AI and ML models enables more realistic forecasts and facilitate near real-time planning & forecasting;

- Smart analytics features like scenario planning prepare for contingencies and quick reaction;

- SAC integrates with a wide range of data sources like S/4HANA , SuccessFactors, SAP IBP, Salesforce etc.

Predictive Planning

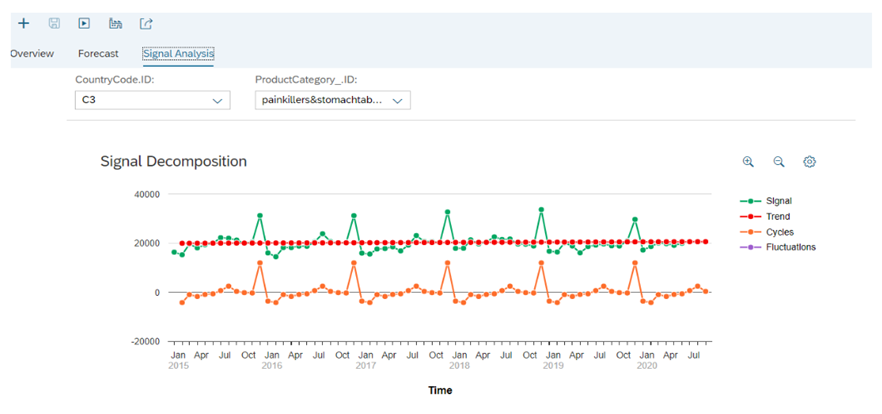

SAC Predictive planning model produces forecasts based on time series. The model is trained with historic data where a statistical algorithm will learn from the data set, i.e. find trends, seasonal variations and fluctuations that characterize the target variable. Upon completion of training, the model produces the forecast as the detailed time series chart for each segment.

In addition to using historical costs to make a prediction, influencer variables can be used to improve the predictive forecasts. Some examples of influencers are energy price when forecasting the energy cost, weather on the day and workday/weekend classification when forecasting daily bike hires.

Influencers are part of the data set and when included in the forecasting model, they contribute towards determining the ‘trend’. They improve the predictive forecasts which can be measured by drop in MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error) and a smaller confidence interval (difference between the Error Max and the Error Min).

Business cases for extension of SAP BPC to SAC

While it may be easier to evaluate the benefits of SAC in a greenfield implementation, it could be challenging to create a suitable business case for customers already using SAP BPC, either standalone or embedded, and interesting to understand how they can preserve their existing assets in a brownfield implementation.

Below we have provided the business case for the 3 planning scenarios for extending the BPC planning to SAC:

Figure: Decomposition of forecast into trend, cycle and fluctuation (left out after trend and cycle are extracted)

Scenario 1: Move planning use cases from BPC to SAC

The ‘Move’ scenario involves re-creation of planning models in SAC. Some of the existing work can be leveraged on; for example, a planning model in SAC can be built through a query coming out of SAP BPC which re-creates the planning dimensions with all their hierarchies. The planning scenarios require more effort as the planning use cases are realized in a different way in SAC than BPC. Functionalities such as disaggregations, version management and simulation are also conceptually different in SAC (compared to BPC).

Note: The re-creation of planning models in SAC through queries from BPC are more relevant for the embedded BPC model, running on SAP BW belonging to S/4 HANA NetWeaver. The integration under a standalone BPC model (using a standalone SAP BW) may not be supported and should be investigated with the vendor.

The key value drivers for this scenario include all the benefits of SAC, such as predictive planning and machine learning, xP&A, modern UX and smart analytics. SAC features on version control, real-time data analysis, lower maintenance cost and faster performance are also possible in the SAP BPC embedded model (advantages over BPC standalone model only).

Scenario 2: Complement existing BPC planning with SAC as planning UX

Here, SAC is used as a tool for entering planning data and data analysis. Data entered in SAC (e.g. via data entry form) is persisted directly in the SAP BPC planning model. LIVE planning is supported only in SAP BPC embedded model (one of the benefits of BPC embedded over standalone).

The key value drivers for this scenario are modern UX and smart analytics (from the firstt scenario), while the functional plans are maintained in BPC.

Scenario 3: Extend BPC with SAC for new functional plans

In this scenario, new functional planning is done in SAC on top of BPC, data is stored in both systems and replicated in both directions.

Key value drivers for this scenario are predictive planning and xP&A (to some extent). A specific use case for the first one is where planning data is brought into SAC, predictive forecasting applied on top of the planned data together with any manual adjustments and data is replicated back to BPC. A use case for the second one is where financial planning done in BPC is integrated with the operational planning done exclusively in SAC.

In conclusion

SAC can be seen as SAP’s vision for Extensible Planning & Analysis (xP&A) as it unifies planning across multiple lines of business while ensuring that plans are meaningful and can be put to action. The predictive time series, AI and ML based models of SAC are key enablers for a near real-time and driver-based planning.

For customers already using BPC (standalone or embedded on S/4 HANA) there are possibilities to complement the existing planning process through SAC. However, to exploit the full benefits in xP&A, it is important to understand the integrated planning approach of SAC which is conceptually different from BPC. While the immediate requirement in a BPC complement scenario could be to realize the current use cases in SAC (in a different way), it makes sense to maintain a strategic outlook, e.g. when creating the planning models in SAC, to achieve the full transformation in future.

References:

Top 10 reasons to move from SAP Business Planning and Consolidation to SAP Analytics Cloud

White-Paper-Extended-Planning-and-Analysis-2022.pdf (fpa-trends.com)

Extended Planning and Analysis | xP&A (sap.com)

SAP Analytics Cloud | BI, Planning, and Predictive Analysis Tools

Hands-On Tutorial: Predictive Planning | SAP Blogs

Predictive Planning – How to use influencers | SAP Blogs

Complement Your SAP Business Planning and Consolidation with SAP Analytics Cloud | SAP Blogs

SAP Business Planning & Consolidation for S/4HANA – In a Nutshell | SAP Blogs

Preventing a next bank failure like Credit Suisse: More capital is not the solution

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

After the collapse of Credit Suisse and the subsequent orchestrated take-over by UBS, there are widespread calls for increasing capital requirements for too big too fail banks to prevent future defaults of such institutions. However, more capital will not prevent the failure of a bank in a bank-run like Credit Suisse experienced in the first quarter of 2023.

A solid capital base is clearly important for a bank to maintain the trust of its clients, counterparties and lenders, including depositors. At the end of 2022, Credit Suisse had a BIS Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratio of 14.1% and a CET1 leverage ratio of 5.4%, in line with its peers and well above regulatory minimum requirements. For example, UBS had a CET1 capital and leverage ratio of 14.2% and 4.4%, respectively. Hence, the capital situation by itself will not have been the reason that depositors and lenders lost trust in the bank, withdrew money in large amounts, refrained from rolling over maturing funding and/or asked for additional collateral.

Why capital does not help

Already during 2022, Credit Suisse experienced a large decrease in funding from customer deposits, falling by CHF 160 billion from CHF 393 billion to CHF 233 billion during the year. In the first quarter of 2023, a further CHF 67 billion of customer deposits were withdrawn. Even if capital could be used to cope with funding outflows (which it cannot, as we will clarify shortly), the amount will never be sufficient to cope with outflows of such magnitude. For comparison, at the end of 2021, Credit Suisse’s CET1 capital was equal to CHF 38.5 billion.

But, as mentioned, capital does not help to cope with funding outflows. A reduction in funding (liabilities) must be either replaced with new funding from other lenders or by a corresponding reduction in assets (e.g., cash or investments), leaving the amount of capital (equity) in principle unchanged[1]. If large amounts of funding are withdrawn at the same time, as was the case for Credit Suisse in 2022, it is usually not feasible to find replacement funding quickly enough at a reasonable price. In that case, there is no alternative to reducing cash and/or selling assets[2].

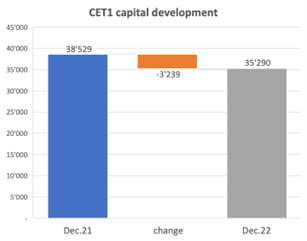

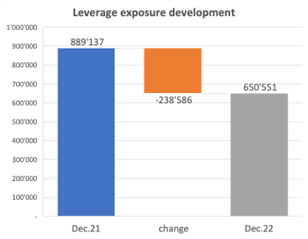

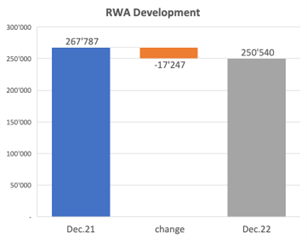

In such a scenario, leverage and capital ratios may actually improve, since the available capital will then support a smaller amount of assets. This is what happened at Credit Suisse during 2022. Although the amount of CET1 capital decreased from CHF 38.5 billion to CHF 35.3 billion (-8.4%), its leverage exposure[3] decreased by 27%. Consequently, the bank’s CET1 leverage ratio improved from 4.3% to 5.4%. Risk-weighted assets (RWA) also decreased, but only by 6%, resulting in a small decrease in the CET1 capital ratio from 14.4% to 14.1%. The changes in CET1 capital, leverage exposure and RWA are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Development in CET1 capital, leverage exposure and risk-weighted assets (RWA) at Credit Suisse between end of December 2021 and end of December 2022 (amounts in CHF million). Source: Credit Suisse Annual Reports 2021 and 2022.

Cash is king

In a situation of large funding withdrawals, it is critical that the bank has a sufficiently large amount of liquid assets. At the end of 2021, Credit Suisse reported CHF 230 billion of liquid assets, consisting of cash held at central banks (CHF 144 billion) and securities[4] that could be pledged to central banks in exchange for cash (CHF 86 billion). At the end of 2022, the amount of liquid assets had decreased to just over CHF 118 billion. Hence, a substantial part of the withdrawal of deposits was met by a reduction in liquid assets. The remainder was met with cash inflows from maturing loans and other assets on the one hand, and replacement with alternative funding on the other.

Lack of sufficient liquid assets was one cause of bank problems during the financial crisis in 2007-08, resulting in extensive liquidity support by central banks. With the aim to prevent this from happening again, the final Basel III rules require banks to satisfy a liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) of at least 100%. This LCR intends to ensure that a bank has sufficient liquidity to sustain significant cash outflows over a 30-day period. The regulatory rules prescribe what cash outflow assumptions need to be made for each type of liability. For example, the FINMA rules for the calculation of the LCR (see FINMA ordinance 2015/2) prescribe that for retail deposits an outflow between 3% and 20% needs to be assumed, with the percentage depending on whether the deposit is insured by a deposit insurance scheme, whether it is on a transactional or non-transactional account, and whether it is a ‘high-value’ deposit. Other outflow assumptions apply to unsecured wholesale funding, secured funding, collateral requirements for derivatives as well as loan and liquidity commitments. The amount of available liquid assets needs to be larger than the cash outflows calculated in this way, net of contractual cash inflows from loans, reverse repos and secured lending within the next 30-day period (all weighted with prescribed percentages). In that case, the LCR exceeds 100% (it is calculated as the amount of liquid assets divided by the difference between assumed cash outflows and contractual cash inflows with prescribed weightings).

At the end of 2022, Credit Suisse had an LCR of 144%, compared to 203% at the end of 2021. Hence, the amount of liquid assets relative to the amount of assumed net cash outflow decreased substantially but remained well above 100%.

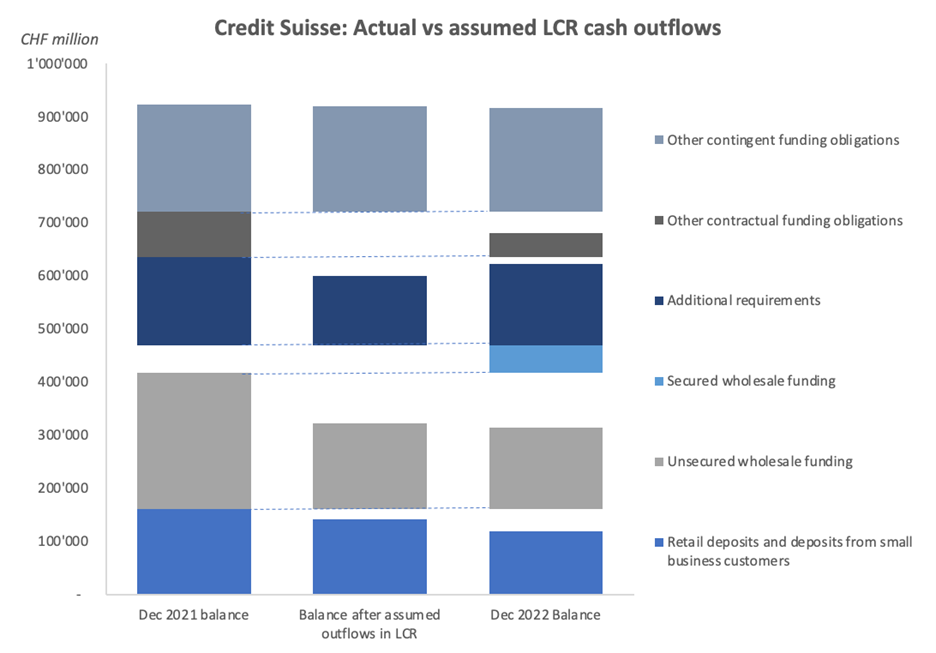

Figure 2 compares the balances of the individual liability categories that are subject to cash outflows in the LCR calculation:

- The first column depicts the actual balances at the end of December 2021.

- The second column shows what the remaining balances would be after applying the cash outflow assumptions in the LCR calculation to the December 2021 balances.

- The third column represents the actual balances at the end of December 2022.

This comparison is not fully fair as we compare the actual balances between the start and the end of the full year of 2022, whereas the assumed cash outflows in the LCR calculation relate to a 30-day period. However, Credit Suisse communicated that the largest outflows occurred during the month of October 2022, so the comparison is still instructive.

Figure 2: Comparison of balances of liability categories[5] that are subject to cash outflow assumptions in the LCR calculation: Actual balances at the end of December 2021 (first column), balances that result when applying the LCR cash outflow assumptions to the December 2021 balances (second column) and actual balances at the end of December 2022 (third column). Source: Credit Suisse Annual Reports 2021 and 2022.

In aggregate, the actual balances at the end of 2022 are higher than the balances that would result after applying the LCR cash outflow assumptions (CHF 714 billion vs CHF 633 billion, compared to CHF 872 billion at the end of 2021). However, for ‘Retail deposits and deposits from small business customers’ and ‘Unsecured wholesale funding’, the actual outflow was higher than assumed in the LCR calculation. This was more than compensated by an increase in secured wholesale funding and lower outflows in other categories than assumed in the LCR calculation.

In summary, the amount of liquid assets that Credit Suisse had were sufficient to absorb the large withdrawal of funds in October 2022 without the LCR falling below 100%. Trust then seemed to be restored, but only until a new wave of withdrawals took place in March of this year, necessitating a request for liquidity support from the Swiss National Bank (SNB). Unfortunately, the liquidity support by the SNB apparently did not suffice to save Credit Suisse.

What if worse comes to worst?

That both retail depositors and wholesale lenders lost trust in Credit Suisse and withdrew large amounts of money cannot be attributed to its capital and leverage ratios by itself, because they were well above minimum requirements and in line with – if not higher than – those of its peers. Apparently, depositors and lenders lost trust because of doubts that are not visible on a balance sheet, for example:

- Doubts whether the bank would be able to stop losses quickly enough when executing the planned strategy, after a loss of CHF 7.2 billion in 2022.

- Doubts about the management quality of the bank after incurring large losses in isolated incidents (Archegos, Greensill).

- Doubts whether provisions taken for outstanding litigation cases would cover the ultimate fines.

Once such and other material doubts arise, possibly fed by rumors in the market, a bank may end up in a negative spiral of fund withdrawals. In such a situation, it will be unclear to lenders and depositors what the actual financial situation is, even though the last reported figures may have been solid. This unclarity will accelerate further withdrawals. As the developments at Credit Suisse have shown, even a very large pool of liquid assets (for Credit Suisse at the end of 2021 more than twice the amount of net cash outflows assumed in the LCR calculation and almost one-third the size of its balance sheet) will then not be enough. Since such a lack of confidence can escalate within a matter of days, as was the case not only for Credit Suisse but for example also for the Silicon Valley Bank as well as Northern Rock in 2008, there is no time to implement a recovery or resolution plan that the bank may have prepared.

Short of implementing a sovereign-money (‘Vollgeld’) banking system, which has various drawbacks as highlighted for example by the Swiss National Bank (SNB), the only realistic solution to save a bank in such a situation is for the government and/or central bank to step in and publicly commit to providing all necessary liquidity to the bank. It is important to note that this does not have to lead to losses for the government (and therefore the tax payer) as long as the capital situation of the bank in question is adequate. For all we know, that was the case at Credit Suisse.

Footnotes

[1] Only if assets are reduced at a value that differs from the book value (e.g., investments are sold below their book value), then this difference will be reflected in the amount of capital.

[2] In the first quarter of 2023, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) supported Credit Suisse with emergency liquidity funding. As a result, short-term borrowings increased from CHF 12 billion to CHF 118 billion during the quarter. This prevented that Credit Suisse had to further reduce its cash position and/or sell assets, possibly at a loss compared to their book value.

[3] The leverage exposure is equal to the bank’s assets plus a number of regulatory adjustments related mainly to derivative financial instruments and off-balance sheet exposures.

[4] At Credit Suisse, these were mostly US and UK government bonds.

[5] The categories ‘Additional requirements’, ‘Other contractual funding obligations’ and ‘Other contingent funding obligations’ comprise mostly (contingent) off-balance sheet commitments, such as liquidity and loan commitments, guarantees and conditional collateralization requirements.

A comparison between Survival Analysis and Migration Matrix Models

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

This article provides a thorough comparison of the Survival Analysis and Migration Matrix approach for modeling losses under the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach and IFRS 9. The optimal approach depends on the bank’s situation, and this article highlights that there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

The focus of this read is on the probability of default (PD) component since IFRS 9 differs mainly with regards to the PD component as compared to the IRB Accords (Bank & Eder, 2021), and that most time and effort is given to this component.

Did you implement one approach and are you now wondering what the other approach would have meant for your IFRS 9 modeling? This article compares the two approaches of IFRS 9 modeling and can, thereby, support in answering the question if this approach is still the best approach for your institution.

Background

As of January 2018, banks reporting under IFRS faced the challenge of calculating their expected credit losses in a different way (IASB, 2023). Although IFRS 9 describes principles for calculating expected credit losses, it is not prescribed exactly how to calculate these losses. This in contrast to the IRB requirements, which prescribe how to calculate (un)expected credit losses. As a consequence, banks had to define the best approach to comply with the IFRS 9 requirements. Based on our experience, we look at two prominent approaches, namely: 1) Survival Analysis and 2) the Migration Matrix approach.

Survival Analysis approach

In the credit risk domain, the basic idea behind Survival Analysis is to estimate how long an obligor remains in the portfolio as of the moment of calculation. Survival Analysis models the time to default instead of the event of default and is therefore considered appropriate for modeling lifetime processes. This approach looks at the number of obligors that are at risk at a certain moment in time and the number of obligors that default during a certain period after that moment. Results are used to construct a cumulative distribution function of the time to default. Finally, the marginal probabilities can be obtained, which, after multiplication with the LGD and EAD, yield an estimation of the expected losses over the entire lifetime of a product.

Survival Analysis is particularly useful in addressing censoring in data, which occurs when the event of interest has not occurred yet for some individuals in the data set. Censoring is generally present in the realm of lifetime PD estimations of loans. Especially mortgage loan data is usually heavily censored due to its large maturity. Therefore, defaults may not yet have occurred in the relatively small data span available.

Various extensions of Survival Analysis are proposed in academic literature, enabling the inclusion of individual characteristics (covariates) that may or may not be varying over time, which is relevant if macroeconomic variables have to be included (PIT vs. TTC). For more background on Survival Analysis used for IFRS 9 PD modeling, please refer to Bank & Eder (2021).

We encounter Survival Analysis models frequently at institutions where credit risk portfolios are not (yet) modeled through advanced IRB models. This is due to the fact that IRB models, more specifically the PD models, form a very good basis for the Migration Matrix approach (see next paragraph). In the absence of IRB models, we observe that many institutions chose for the Survival Analysis approach in order to end with one single model, rather than two separate models.

One of the issues when using the Survival Analysis approach is that banks need to develop IRB and IFRS 9 PD models independently, which generally require different data sources and structures, and various methodologies for calculating PD. Consequently, inconsistencies in the estimated PD have been observed due to the utilization of different models and misalignment of IRB and IFRS 9 results. An example of such an inconsistency is an observed increase in estimated creditworthiness according to the IRB PD model, while the IFRS 9 PD decreases. Therefore, banks that chose to independently develop IRB and IFRS 9 PD models have regularly encountered difficulties in explaining these differences to regulators and management.

Migration Matrix approach

The existing infrastructure for estimating the expected loss for capital adequacy purposes, as prescribed by IRB, may be used as source to accommodate the use of IFRS 9 provision modeling. This finding is supported by a monitoring report published by the EBA, which indicates that 59% of the institutions examined have a dependence of their IFRS 9 on their IRB model (EBA, 2021).

IRB outcomes can be used as feeder model for IFRS 9 by utilizing migration matrices. Migration matrices can be established based on the existing rating system, i.e. the IRB rating system used for capital requirements. Each of these ratings can be seen as a state of a Markov Chain, for which the migration probabilities are illustrated in a Migration Matrix. Consequently, along with the probability of default, transformations in creditworthiness may also be observed. A convenient feature of this approach is the ability to extend the horizon on which the PD is estimated by straightforward matrix multiplication. This is especially useful for complying with both IRB and IFRS 9 regulations, where 12-month and multi-period predictions are required, respectively.

Estimating the PD under IRB and IFRS 9 comes with an additional challenge; PDs for capital are required to be Through-The-Cycle (TTC), while IFRS 9 requires them to be Point-In-Time (PIT), depending on macro-economic conditions. A popular model that facilitates the conversion between these two objectives is the Single Factor Vasicek Model (Vasicek, 2002).This model shocks the TTC Migration Matrix with a single risk factor, Z, which is dependent on macroeconomic risk drivers. Consequently, PIT migration matrices are attained, conditional on a future value of Z. Forecasting Z multiple periods ahead enables one to create a series of PIT transition matrices that can be viewed as a time-inhomogeneous Markov Chain. Subsequently, lifetime estimates of the PDs can be calculated by multiplying these matrices.

One of the main issues in applying the migration matrix approach is that you cannot redevelop or recalibrate IRB and IFRS 9 models in parallel. You require to first finish the IRB model before you finish your IFRS 9 model.

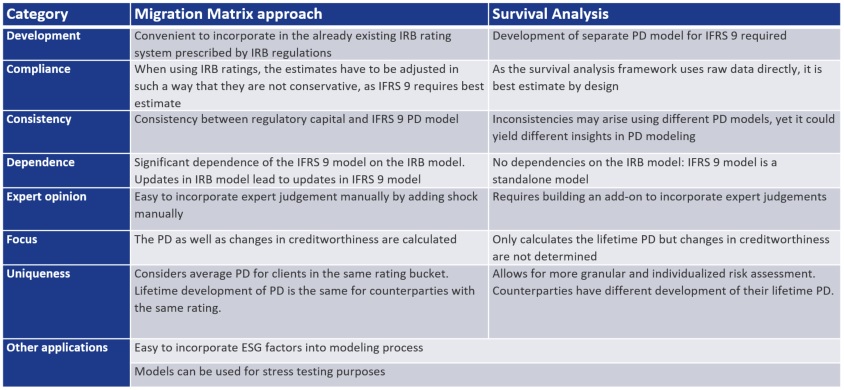

Comparison Migration Matrix approach and Survival Analysis

We will now zoom in on the differences between the two approaches mentioned above. This doesn’t imply that these approaches do not share characteristics. Commonalities are, amongst other, that both approaches yield an estimate for future PD, can incorporate macro-economic expectations and are often used during stress test exercises. Table 1 presents a summary of the key features of both the Migration Matrix approach and Survival Analysis, and their interrelationships. The Migration Matrix approach is characterized by its use of a unified PD structure. When estimating different PDs for IRB and IFRS 9, this allows for a simpler explanation on why these differ. Survival Analysis offers the advantage of estimating PD on a per-obligor basis, as opposed to the Migration Matrix approach, which calculates the average PD per rating category. Accordingly, the Migration Matrix approach operates under the assumption that obligors within the same rating category possess similar average PDs over the long term which might not be true.

Whilst the above constitute the primary differences, the two approaches demonstrate many variations across the diverse categories in Table 1. Accordingly, each situation may require a distinct optimal approach implying the absence of a universal best practice.

Table 1: Migration Matrix approach vs Survival Analysis

The table of differences indicates that selecting the best approach can be challenging as both approaches have their respective advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and the optimal choice depends on the specific institution’s situation. Fortunately, our experts in this field are available and eager to collaborate with you in identifying and implementing the best possible modeling approach for your institution.

References:

Bank, M., & Eder, B. (2021). A review on the Probability of Default for IFRS 9. Available at SSRN 3981339.

Gae-Carrasco, C. (2015). IFRS 9 Will Significantly Impact Banks’ Provisions and Financial Statements. Moody’s Analytics Risk Perspectives.

IASB (2023). IFRS 9 Financial Instruments. Retrieved from https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ifrs-9-financial-instruments/

Vasicek, O. (2002). The distribution of loan portfolio value. Risk, 160-162.

CEO Statement: Why Our Purpose Matters

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

The Zanders purpose

Our purpose is to deliver financial performance when it counts, to propel organizations, economies, and the world forward.

Recently, we have embarked on a process to align more effectively what we do with the changing needs of our clients in unprecedented times. A central pillar of this exercise was an in-depth dialogue with our clients and business partners around the world. These conversations confirmed that Zanders is trusted to translate our deep financial consultancy knowledge into solutions that answer the biggest and most complex problems faced by the world's most dynamic organizations. Our goal is to help these organizations withstand the current macroeconomic challenges and help them emerge stronger. Our purpose is grounded on the above.

"Zanders is trusted to translate our deep financial consultancy knowledge into solutions, answering the biggest and most complex problems faced by the world's most dynamic organizations."

Laurens Tijdhof

Our purpose is a reflection of what we do now, but it's also about what we need to do in the future.

It reflects our ongoing ambition - it's a statement of intent - that we should and will do more to affect positive change for both the shareholders of today and the stakeholders of tomorrow. We don't see that kind of ambition as ambitious; we see it as necessary.

The Zanders’ purpose is about the future. But it's also about where we find ourselves right now - a pandemic, high inflation and rising interest rates. And of course, climate change. At this year's Davos meeting, the latest Disruption Index was released showing how macroeconomic volatility has increased 200% since 2017, compared to just 4% between 2011 and 2016.

So, you have geopolitical volatility and financial uncertainty fused with a shifting landscape of regulation, digitalization, and sustainability. All of this is happening at once, and all of it is happening at speed.

The current macro environment has resulted in cost pressures and the need to discover new sources of value and growth. This requires an agile and adaptive approach. At Zanders, we combine a wealth of expertise with cutting-edge models and technologies to help our clients uncover hidden risks and capitalize on unseen opportunities.

However, it can't be solely about driving performance during stable times. This has limited value these days. It must be about delivering performance despite macroeconomic headwinds.

For over 30 years, through the bears, the bulls, and black swans, organizations have trusted Zanders to deliver financial performance when it matters most. We've earned the trust of CFOs, CROs, corporate treasurers and risk managers by delivering results that matter, whether it's capital structures, profitability, reputation or the environment. Our promise of "performance when it counts" isn't just a catchphrase, but a way to help clients drive their organizations, economies, and the world forward.

"For over 30 years, through the bears, the bulls, and black swans, financial guardians have trusted Zanders to deliver financial performance when it matters most."

Laurens Tijdhof

What "performance when it counts" means.

Navigating the current changing financial environment is easier when you've been through past storms. At Zanders, our global team has experts who have seen multiple economic cycles. For instance, the current inflationary environment echoes the Great Inflation of the 1970s. The last 12 months may also go down in history as another "perfect storm," much like the global financial crisis of 2008. Our organization's ability to help business and government leaders prepare for what's next comes from a deep understanding of past economic events. This is a key aspect of delivering performance when it counts.

The other side of that coin is understanding what's coming over the horizon. Performance when it counts means saying to clients, "Have you considered these topics?" or "Are you prepared to limit the downside or optimize the upside when it comes to the changing payments landscape, AI, Blockchain, or ESG?" Waiting for things to happen is not advisable since they happen to you, rather than to your advantage. Performance when it counts drives us to provide answers when clients need them, even if they didn't know they needed them. This is what our relationships are about. Our expertise may lie in treasury and risk, but our role is that of a financial performance partner to our clients.

How technology factors into delivering performance when it counts.

Technology plays a critical role in both Treasury and Risk. Real-time Treasury used to be an objective, but it's now an imperative. Global businesses operate around the clock, and even those in a single market have customers who demand a 24/7/365 experience. We help transform our clients to create digitized, data-driven treasury functions that power strategy and value in this real-time global economy.

On the risk management front, technology has a two-fold power to drive performance. We use risk models to mitigate risk effectively, but we also innovate with new applications and technologies. This allows us to repurpose risk models to identify new opportunities within a bank's book of business.

We can also leverage intelligent automation to perform processes at a fraction of the cost, speed, and with zero errors. In today's digital world, this combination of next generation thinking, and technology is a key driver of our ability to deliver performance in new and exciting ways.

"It’s a digital world. This combination of next generation of thinking and next generation of technologies is absolutely a key driver of our ability to deliver performance when it counts in new and exciting ways."

Laurens Tijdhof

How our purpose shapes Zanders as a business.

In closing, our purpose is what drives each of us day in and day out, and it's critical because there has never been more at stake. The volume of data, velocity of change, and market volatility are disrupting business models. Our role is to help clients translate unprecedented change into sustainable value, and our purpose acts as our North Star in this journey.

Moreover, our purpose will shape the future of our business by attracting the best talent from around the world and motivating them to bring their best to work for our clients every day.

"Our role is to help our clients translate unprecedented change into sustainable value, and our purpose acts as our North Star in this journey."

Laurens Tijdhof

Demystifying blockchain security risks

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

To fully leverage the benefits of this technology, it’s essential to understand and address security threats when implementing blockchain solutions.

As a decentralized distributed ledger technology, blockchain can add value as a platform that integrates a corporate’s operational processes with its treasury processes. This could drive treasury efficiencies and reduce cycle times. Also, compared to centralized systems, blockchain provides benefits of enhanced security. However, these benefits also have a downside. Recent reports of large-scale hacks and frauds involving hundreds of millions of dollars have shed light on the potential security risks associated with blockchain.

Phishing attacks

One of the most prevalent security risks are phishing attacks on crypto wallets. A crypto wallet is a software that securely stores and manages crypto assets, enabling users to send and receive digital assets. These attacks trick users into providing their private keys, a password to access the crypto funds, which can then be used to steal their crypto assets.

It’s worth noting that most successful phishing attacks are the result of incorrect user behavior, such as clicking on malicious links and providing login credentials. While this is a widespread IT security risk and not specifically related to the security of the blockchain technology itself, it remains a critical risk worthy of attention.

Options to protect against phishing are using a two-factor authentication system, having good security awareness trainings for users and/or using the security services of a reputable custodian.

Smart contracts exploits

Smart contracts are self-executing contracts with the terms of the agreement written directly into code and are run on a blockchain network such as Ethereum, Solana or Avalanche among others. They offer a high level of transparency and security, but they are also vulnerable to hacking and exploitation if not written correctly. A well-publicized example of this was the hack of a Compound smart contract, a blockchain protocol on the Ethereum network that enables algometric money markets, where a vulnerability in the code allowed the hacker to steal a large amount of Compound tokens.1

To prevent such incidents, it’s crucial to have independent security audits performed on all smart contracts and to follow best practices for smart contract development. Another line of defense is to opt for insurance with a specialized blockchain insurance company which can provide coverage against losses caused by platform failures, smart contract exploits or other risks.

Bridge hacks

Approximately 50% of exploits in value terms in decentralized finance occur on bridges.2 Bridges are connecting mechanisms that allow different blockchain networks to communicate with each other and are gaining popularity for their ability to facilitate seamless asset transfers and integrate the features provided by the different blockchains.

Two main types of bridges exists:

- Centralized Bridges: Use of central party, offers a straightforward solution but requires trust in the third party and often not transparent.

- Decentralized Bridges: Use of smart contracts provide increased transparency but may be prone to vulnerabilities due to the complexity of their design.

Due to the large amounts of funds locked in these bridges it made them attractive targets for hackers. Therefore it is advisable to conduct thorough research when selecting a bridge to work with and to regularly monitor the security measures in place.

Ponzi schemes & fraud

A Ponzi scheme is a type of crypto fraud that promises high returns with little to no risk. In this type of fraud, early investors are paid returns from the investments of later investors, creating the illusion of a profitable investment opportunity. Eventually, the scheme collapses when there are not enough new investors to pay the returns promised to earlier ones. Famous examples are Bitconnect and Plus tokens which caused multibillion losses and over two millions investors impacted.3 Another prevalent form of fraud in the blockchain industry is the misappropriation of customer funds by insiders or company leadership, as evidenced by the ongoing FTX case4, involving 8 billion dollars, where fraud allegations have been raised.

To avoid falling victim to Ponzi schemes or fraud, companies and retail investors dealing in cryptocurrency must perform due diligence before investing in any opportunity. This includes verifying the authenticity of the investment opportunity and the individuals behind it. Companies should also avoid investments that promise guaranteed high returns with little to no risk, as these are often warning signs.

Blockchain network security

Despite these challenges, blockchain technology as a whole is relatively secure. The decentralized nature of blockchain networks makes it more difficult for malicious actors to manipulate or attack the system, as there is no central point of control that can be targeted. Additionally, cryptographic techniques such as hashing, digital signatures, and consensus algorithms help to ensure the integrity and security of the data stored on the blockchain. The robustness of this technology is evident from the fact that popular and established networks such as Bitcoin and Ethereum have not faced any successful exploits or attacks over the years . However, there have been instances of successful hacks and attacks on less popular blockchain networks.

In conclusion

The utilization of blockchain technology in various industries has the potential to revolutionize the way we conduct transactions and manage data. However, it’s imperative to weigh the benefits against the potential security risks. From phishing attacks on wallets to Ponzi schemes and smart contract risks, organizations must take the necessary precautions to ensure their assets are protected including:

- Use two-factor authentication, have security awareness trainings, and/or use services from a reputable custodian to protect against phishing attacks on crypto wallets.

- Have independent security audits of your smart contracts and consider taking specialized insurance.

- Conduct thorough research when selecting a bridge and regularly monitor the security measures in place.

- Perform due diligence before investing and avoid promises of high returns with little risk.

- Be cautious when dealing with less popular blockchain networks.

Zanders Blockchain Consulting Services

For Treasurers, the need for reliable and real-time data is great when working with multiple (external) stakeholders on a single process. Blockchain offers valuable support in this regard. It can also help with the creation of smart contracts or the use of crypto within the payment process. Since recently, Zanders offers blockchain consulting services to support corporates, financial institutions and public sector entities in reaping the benefits of blockchain and managing its additional security risks. By focusing on understanding the why of its application, and drafting a blueprint of the preferred solution, we can help define the business case for using blockchain. Subsequently, we can help selecting the best technology platform and third parties.

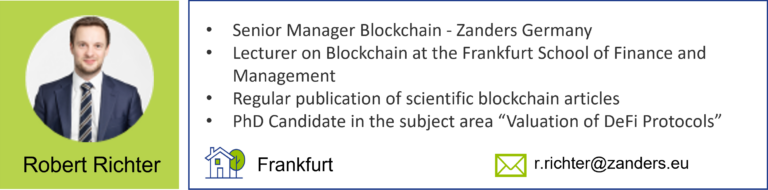

If you would like to discuss how blockchain, digital assets or Web3 can impact your business, please reach out to our experts, Ian Haegemans, Robert Richter or Justus Schleicher via +31 88 991 02 00.

Sources

(1) https://www.coindesk.com/business/2021/10/03/66m-in-tokens-added-to-recently-hacked-still-vulnerable-compound-contract

(2) Report: Half of all DeFi exploits are cross-bridge hacks (cointelegraph.com)

(3) https://blockchain.news/news/chinese-police-arrest-kingpins-plus-token-bitcoin-scam-worth-5-7-billion

(4) https://www.ft.com/content/6613eadb-eea0-42f8-8d92-fe46ad8fcf8c

ISO 20022 MT MX migration – What does this really mean for Corporate Treasury?

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

The start of the migration from the SWIFT FIN format to the new ISO 20022 XML format, which is a banking industry migration that must be completed by November 2025.

Whilst at this stage the focus is primarily on the interbank space, there will be some impact on corporate treasury within this migration period. Zanders experts Eliane Eysackers and Mark Sutton demystify what is now happening in the global financial messaging space, including the possible impacts, challenges and opportunities that could now exist.

What is changing?

The SWIFT MT-MX migration is initially focused on a limited number of SWIFT FIN messages within the cash management space – what are referred to as category 1 (customer payments and cheques), 2 (financial institution transfers) and 9 (cash management and customer status) series messages. This can translate to cross border payments (e.g., MT103, MT202) in addition to the associated balance and transaction reporting (e.g., MT940, MT942) within the interbank messaging space.

Is corporate treasury impacted during the migration phase?

This is an interesting and relevant question. Whilst the actual MT-MX migration is focused on the interbank messaging space, which means existing SWIFT SCORE (Standardised Corporate Environment), SWIFT MACUGs (member administered closed user groups) and of course proprietary host to host connections should not be impacted directly, there could be a knock-on effect in the following key areas:

- The first issue pertains to cross-border payments, which are linked to the address data required in interbank payments. As the financial industry is looking to leverage more structured information, this could create a friction point as both the MT101 and MT103 SWIFT messages that are used in the corporate to bank space only supports unstructured address data. This problem will could also exist where a legacy bank proprietary file format is being used, as these have also typically just offered unstructured address data. This could mean corporates will need to update the current address logic and possibly the actual file format that is being used in the corporate to bank space.

- Secondly, whilst banking partners are expected to continue providing the MT940 end of day balance and transaction report post November 2025, there is now a risk where a corporate is using a proprietary bank statement consolidation service. Today, a global corporate might prefer not to connect directly to its local in-country banking partners as payment volumes are low. Under these circumstances the local in-country banks might be sending the MT940 bank statement to the core banking partner, who will then send this directly to the corporate. However, after November 2025, these local in-country banks will not be able to send the MT940 statement over the SWIFT interbank network, it will only be possible to send the camt.053 xml bank statement to the core banking partner. So from November 2025, if the core banking partner cannot back synchronise the camt.053 statement to the legacy MT940 statement, this will require the corporate to also migrate onto the camt.053 end of day bank statement or consider other alternatives.

- Finally, from November 2025, the camt.053 xml bank statement will be the defacto interbank statement format. This provides the opportunity for much richer and more structured statement as the camt.053 message has almost 1,600 fields. There is therefore an opportunity cost if the data is force truncated to be compatible with the legacy MT940 statement format.

So, what are the benefits of moving to ISO20022 MX migration

At a high level, the benefits of ISO 20022 XML financial messaging can be boiled down into the richness of data that can be supported through the ISO 20022 XML messages. You have a rich data structure, so each data point should have its own unique xml field. Focusing purely on the payment’s domain, the xml payment message can support virtually all payment types globally, so this provides a unique opportunity to both simplify and standardise your customer to bank payment format. Moving onto reporting, the camt.053 statement report has almost 1,600 fields, which highlights the richness of information that can be supported in a more structured way. The diagram below highlights the key benefits of ISO20022 XML messaging.

Fig 1: Key benefits of ISO20022 XML messaging

What are the key challenges around adoption for corporate treasury?

Zanders foresees several challenges for corporate treasury around the impact of the SWIFT MT to MX migration, primarily linked to corporate technical landscape and system capabilities, software partner capabilities and finally, partner bank capabilities. All these areas are interlinked and need to be fully considered.

What are my next steps?

ISO20022 is now the de-facto standard globally within the financial messaging space – SWIFT is currently estimating that by 2025, 80% of the RTGS volumes will be ISO 20022 based with all reserve currencies either live or having declared a live date.

However, given the typical multi-banking corporate eco-system, Zanders believes the time is now right to conduct a more formal impact assessment of this current eco-system. There will be a number of key questions that now need to be considered as part of this analysis, including:

- Considering the MT-MX migration will be using the xml messages from the 2019 ISO standards release, what are my partner banks doing around the adoption of these messages for the corporate community?

- If I am currently using XML messages to make payments, do I need to change anything?

- Do I currently use a statement reporting consolidator service and how will this be impacted?

- How is my address data currently set-up and does my existing system support a structured address?

- What are my opportunities to drive greater value out this exercise?

In Summary

The corporate treasury community can reap substantial benefits from the ISO 20022 XML financial messages, which offer more structured and comprehensive data in addition to a more globally standardized format. Making the timing ideal for corporates to further analyse and assess the positive impact ISO 20022 can have on the key questions proposed above

Global disruptions demand Treasuries to act fast

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

In today’s world, supply chain disruptions are consequences of operating in an integrated and highly specialized global economy. Along with affecting the credit risk of impacted suppliers, these disruptions are demanding Treasuries to operate with increased working capital.

In March 2021, a vessel was forced aground due to intense winds at Egypt’s Suez Canal, creating a bottleneck involving 100 ships. Given that the Suez Canal accommodates 12% of global trade and the fact that one-tenth of the daily total global oil consumption was caught in the bottleneck, it was no surprise that the international oil market was rattled, and numerous supply chains were affected.1

A butterfly effect

This is reminiscent of a concept known as butterfly effect, where a minor fluctuation such as a butterfly flapping its wings proves to have an effect, however small, on the path a tornado takes on the other side of the globe.

To further complicate matters, this disruption transpired when the global shipping industry was already destabilized due to the coronavirus pandemic.2 This pandemic affected the global economy and supply chains in particular like no other event in the past several decades. Entire cities were locked down and many businesses were at a standstill. It may be impossible to predict black swan events that disrupt global supply chains. However, it is possible to reach fairly accurate assumptions about certain supply chains based on knowledge at hand.

Leveraging supply chains

The Russian invasion of Ukraine will no doubt impact the industries that have suppliers in Ukraine. Another lockdown in China will have repercussions for the supply chains intertwined there. With these types of constraints on the supply chains, procurement divisions are stocking up on inventory and raw materials, which in turn further aggravates the inflation problem the global economy is currently facing. Issues like these are demanding many treasurers to operate with increased working capital, along with affecting the credit risk of impacted suppliers. Treasurers around the world should act fast to take advantage of the financial benefits that today’s global economy is bestowing on organizations that are quick to adapt to the constantly changing business environment. Treasurers can even start leveraging supply chains to work in their favor by utilizing Supply Chain Finance (SCF) solutions.

Decreasing the DSO

What does the concept of SCF mean and what are its implications? Let’s start with the different parties involved in a typical SCF transaction, like reverse factoring. We have the supplier, the buyer, and the bank. Let’s suppose the buyer enters an agreement to purchase goods from the supplier. In most cases, the supplier will ship the goods to the buyer on credit. The payment terms may vary from 10 days to 60 or more days. The average number of days it takes a company to receive payment for a sale is known as days sales outstanding (DSO). The objective of companies is to keep the DSO as low as possible. This implies that the supplier is receiving its payments quickly from the buyer and has a positive effect on the cash conversion cycle (CCC) of the supplier. The CCC indicates how many days it takes a company to convert cash into inventory and back into cash during the sales process. Unfortunately, many companies struggle with a high DSO, which suggests they are either experiencing delays in receiving payments or have long payment terms. A high DSO can lead to cash flow problems, but implementing a SCF solution might be wise response. Having a healthy working capital is a cornerstone to building a successful business, especially for growing and/or leveraged companies.

Why cash flow is crucial

American billionaire businessman Michael Dell once acknowledged: “We were always focused on our profit and loss statement. But cash flow was not a regularly discussed topic. It was as if we were driving along, watching only the speedometer, when in fact we were running out of gas.3

A company may be profitable, but if it has poor cash flow, it will struggle to meet its liabilities or properly invest its excess cash. Because cash is a crucial element to a successful business, companies will strategically hold onto it as long as possible. If their credit terms indicate that they have 30 days to pay an invoice, it is quite likely that they will wait as close to the deadline as possible before they make the payment.

Furthermore, a buyer with a strong credit rating and powerful brand recognition may demand more generous credit terms. These considerations affect a financial ratio known as days payable outstanding (DPO). The DPO indicates the average time that a company takes to pay its invoices. A higher DPO implies that a company can maximize its working capital by retaining cash for a longer duration. This cash can be used for short-term investments or other purposes that a company determines will optimize its finances. However, a high DPO can also indicate that the company is struggling to meet its financial obligations.

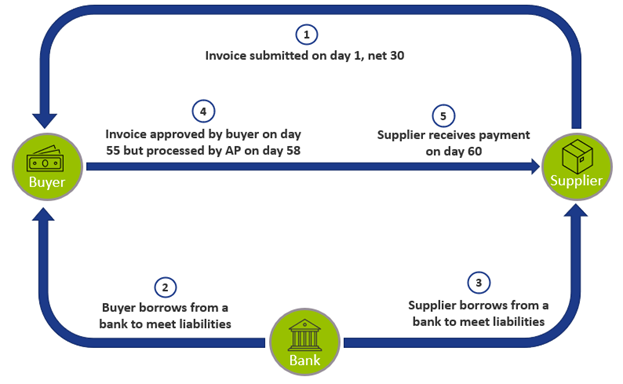

An example

The diagram below depicts a scenario where the supplier invoices the buyer, hoping to receive payment in 30 days. Unfortunately, the buyer needs funds for its operating activities, and furthermore must borrow from the bank to meet its liabilities. It is also possible that the buyer pays late so it can hold onto cash longer or due to roadblocks in the invoice approval process. In the meantime, the supplier is also experiencing cash flow challenges, and it too borrows from the bank. (Of course, both the buyer and the supplier could also use a revolving credit line to access capital, but to simplify this example, we will assume they are borrowing from the bank). The buyer eventually approves the invoice for payment on day 55 and the supplier receives the payment on day 60. The buyer has a high DPO at the expense of the supplier also having a high DSO.

Figure 1: A scenario of a supplier hoping to receive payment in 30 days.

Reverse factoring

What can a company do if it is struggling with its working capital? Suppose a supplier has a dozen buyers, some which pay on time, but others unfortunately are facing their own cash flow problems and are not able to pay within the agreed terms. Wouldn’t it be nice to receive payment within a week from some of the buyers to avoid having a cash flow problem? SCF offers a solution.

To help illustrate this concept, let’s explore a more familiar financial concept known as factoring. With factoring, a company sells its accounts receivable to a third party. SCF is sometimes knowns as ‘reverse factoring’, because a supplier will leverage a buyer’s strong credit rating and select certain invoices to be paid early by a third-party financier, typically a bank. The buyer would then be responsible for paying the bank. In certain types of SCF arrangements, instead of paying an invoice in 30 days, the bank will offer the buyer to pay in, let’s say, 60 days – but for a fee. This could potentially increase the buyer’s DPO.

The supplier, on the other hand, receives its payment sooner from the bank – reducing its DSO – than it would have from the buyer, but at a discount. It is important to note that the discount should be less than the interest the supplier would have incurred if it had borrowed from the bank. This is possible because the discount is calculated based on the creditworthiness of the buyer, instead of the supplier. Many suppliers who lack credit or have poor credit would find this an advantageous option to access cash. However, not all suppliers may be able to reap the benefits of an SCF agreement. For them, borrowing from a bank or factoring receivables are additional options they can explore.

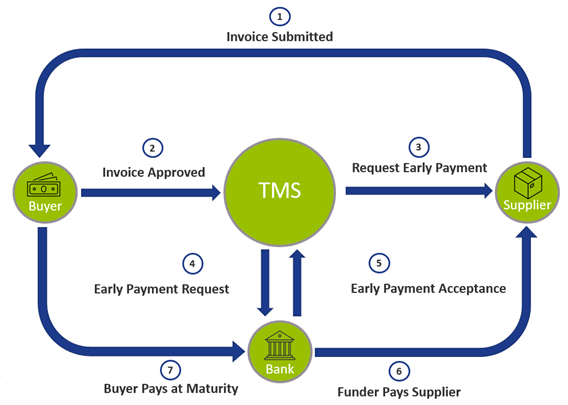

Dynamic discounting

Another term often used when discussing these types of financing options is dynamic discounting. This is similar to reverse factoring in that a supplier receives early payment on an invoice at a discount. However, unlike SCF, dynamic discounting is financed by the buyer as opposed to a third-party financier. Due to the complexity of SCF arrangements between the suppler, the buyer, and the bank, a company often uses the expertise of banks or the capability of a Treasury Management System (TMS). Below is a diagram of what an SCF solution would look like utilizing a TMS:

Whether a company should implement a TMS, which vendor it should utilize, and determining if SCF is a viable solution for that organization are complex questions. Furthermore, because of the globalized environment that companies operate in and the impact of crises like the coronavirus pandemic or a bottleneck at a major canal, an increasing number of organizations are turning to the expertise of consultants to help navigate these intricate matters.

Zanders’ SCF solutions

Zanders is a world-leading consultancy firm specializing in treasury, risk, and finance. It employs over 250 professionals in 9 countries across 4 continents. Powered by almost 30 years of experience and driven by innovation, Zanders has an extensive track record of working with corporations, financial institutions, and public sector entities. Leveraging this extensive background, Zanders can evaluate the assorted options that organizations are exploring to enhance their treasury functions.

With its unique market position, Zanders is able to engage in projects ‘from ideas to implementation’. Whether organizations are trying to stay afloat in today’s challenging global economy or seeking to stay ahead of the curve, they should reap the benefits of modern technology and various SCF solutions that are currently being offered in today’s dynamic business environment. Amid a rapidly changing world being transformed by technological advancement, Zanders welcomes the opportunity to assist clients achieve their treasury and finance objectives.

If you’re interested in learning more about Supply Chain Finance and how your Treasury can properly anticipate disruptions in global supply chains, please reach out to Arif Ali via +1 6467703875.

Footnotes:

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/world/middleeast/suez-canal-blocked-ship.html

A solvent wind-down of trading books and its challenges

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

Large systemic financial institutions have to show that they are resolvable during times of great stress. In this article, we discuss a specific requirement for resolution planning: the solvent wind-down (SWD) of trading books. We explain the requirements, discuss our findings and highlight key challenges during the development of the SWD plan and playbook.

Solvent wind-down (SWD) is regulated by the European Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) and supervised by the Single Resolution Board (SRB). Banks must demonstrate, by means of an SWD plan that they can exit their trading activities in an orderly manner while avoiding posing risks to the stability of the financial system. The SWD guidance1 sets out the necessary steps and initiatives for banks to take, structured along seven dimensions2 from the Expectations for Banks publication3, to ensure they are resolvable and to demonstrate their preparedness for a potential resolution.

Winding down requirements

Banks with material trading books4 are expected to develop a granular plan to prove their capability to wind-down their trading books. Winding down trading books requires careful planning and analytical capabilities, including:

- An SWD plan outlining the different segments5 and associated exit strategies for its trading activities and the potential financial implications. The plan should include an initial snapshot (taken ‘today’) providing a description of the trades and desks as the starting point of the wind-down period and a target snapshot providing positions targeted for the ‘rump’ portfolio, i.e. the positions that remain in the trading book after the wind-down period. Furthermore, the plan should determine the exit, risk-based and operational costs, and assess the impact on liquidity and risk-weighted assets (RWA).

- Information provision on SWD planning, such as the capacity to update the plan on a regular basis and in a timely manner, using business as usual (BaU) tools, systems, and infrastructures as much as possible.

- Constructing an SWD playbook that focusses on governance, HR and communication as defined in the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) discussion paper. The FSB paper6 sets out considerations related to the solvent wind-down of the derivative portfolio activities of a G-SIB that may be relevant for authorities and firms for both recovery and resolution planning. The playbook should provide clarity on the necessary steps and actions taken during the wind-down period, including, identification of the parties involved in the decision-making, their responsibilities and communication with relevant stakeholders.

The SWD plan outlines the technical aspects of winding down the trading book while the SWD playbook describes the process of how to execute the exit strategy. Banks are expected to initially provide the day-one requirements for the SWD plan and playbook. Thereafter, the SWD plan and playbook need to be expanded and improved to meet the steady-state requirements. This entails a comprehensive upgrade, providing a more granular analysis and the ability to update the exit strategies based on the latest balance sheet within five working days. Note that the bank management could decide to wind down only a few desks. The SWD plan could therefore include multiple scenarios in which different parts of the trading book are wound down.

By 2021, all G-SIBs received instructions from the SRB to work on SWD planning as a Resolution Planning Cycle (RPC) 2022 priority. Other banks have been identified and approached by the SRB in the course of 2022 following a further assessment of the significance of their trading books, to work on SWD planning as an RPC 2023 priority.

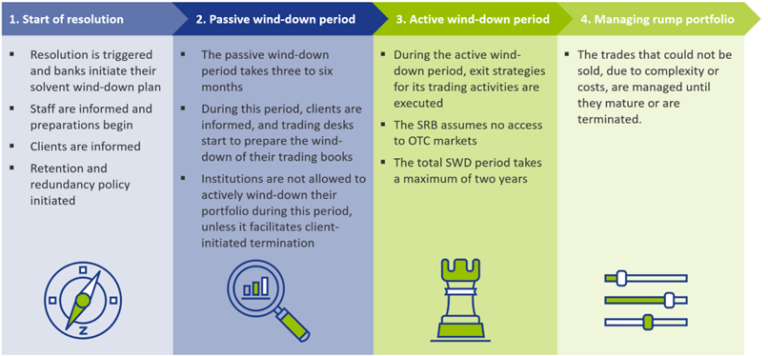

SWD of the trading books

When resolution is triggered, the bank must execute its SWD plan which consists of the four phases indicated in Figure 1. During the first phase, staff and clients are informed and the SWD plan is updated based on the latest trading book status. Then, during the passive wind-down period, trading desks start the preparations to wind down their trading books. During this period, no active trading is allowed, unless specifically requested by the client. During the active wind-down period, exit strategies are executed, while not being able to access the over-the-counter (OTC) market. The bank is required to update their sensitivities (Greeks), costs of winding down, operational costs, and impact on liquidity and RWAs on a quarterly frequency for the full wind-down period. Finally, after two years, most of the trading activities should have been wound down and the few remaining trades that could not be sold, are managed until they mature or are terminated.

Challenges and how to address them

Creating a streamlined process to update the SWD plan

One of the larger challenges is to create a streamlined process that enables an update of all exposures and exit strategies for the entire trading book within five working days, which is a steady-state requirement. Since information is usually gathered from various data sources, it can be difficult to update the SWD plan in a timely manner. Therefore, smart tooling should be developed that can assign exit strategies and priorities to certain types of trades to plan the unwinding in the two-year window.

Winding down complex books

Banks with complex or structured books, with positions falling under level 3 of the IFRS13 accounting standards7, could face difficulties unwinding these positions (from a process or cost perspective). These more complex products are usually less liquid, because inputs required to determine the market value are unobservable (by definition, or for example due to low market activity). Banks should provide evidence that they are aware of this complexity and should be able to come up with a reasonable estimate of the costs of unwinding, for example by using the bid/offer spread (if available) and a haircut.

No access to the OTC markets for hedging purposes

One of the assumptions set by the SRB is that the bank has failed to maintain, establish, or re-establish market confidence. Under this assumption, banks cannot continue using the bilateral OTC markets. Consequently, only listed products can be used for hedging purposes. This could result in imperfect hedges and possibly higher exit costs when selling or auctioning trades (please note that trades are often auctioned in groups, i.e. auction packages are created). Additionally, a bank must show how it expects the exit and risk-based costs to evolve during the solvent wind-down period, taking into consideration the changes in the composition of its trading book. To tackle the above two challenges, banks could find ‘natural’ hedges with offsetting risks in the trading books to reduce the risk sensitivity of auction packages. Packages with lower risks are expected to have lower exit costs. In turn, the bank can calculate the exit and risk-based costs for each package in each quarter of the active wind-down phase.

Measuring the impact on RWAs for market risk

Banks are expected to include the potential impact of winding down their portfolios on sensitivities, costs (exit, risk-based and operational), liquidity and RWAs (for market, credit and operational risks) in the SWD plan. This impact analysis must be presented, at least quarterly, during the two-year wind-down period. To measure the impact on the RWAs for market risk, banks are challenged to add the hedges that they want to use during the resolution period in their system. Subsequently, banks should be able to age their portfolio: i.e. banks need to calculate the impact of maturing, terminating, and auctioning of trades in their trading books during the entire wind-down period. If this functionality is not readily available, banks may need to use an alternative method to determine the impact. A possibility to tackle this challenge is to create ‘test’ books, which include listed/cleared trades that will be used for hedging purposes during the active wind-down period.

Liquidity gaps

Finally, the SWD plan should contain an analysis of the impact on liquidity. As banks are in resolution, major cash shortfalls could occur. A thorough analysis of outflows and inflows is necessary to identify potential future cash flow mismatches. One important assumption is that the bank in resolution will lose its investment grade or experience a downgrade of its credit rating, likely resulting in significant collateral/margin calls and potentially creating liquidity gaps. These gaps need to be identified and explained. Banks could prioritize the auction/novation of trades with credit support annexes (CSAs) that have high collateral requirements to close the CSA and free up capital.

Outlook for the future

Over time, the SRB is likely to amend the guidance on SWD of trading books. The most recent publication date (at the time of writing) is December 2021. We expect that more granular reporting will be required in the future. Additionally, we expect that banks will be required to perform stress testing on their trading books, which may be challenging to incorporate. Nonetheless, no changes to the guidance are expected in 2023.

In conclusion

Creating a solvent wind-down strategy can be very complex and introduce many challenges to banks. A large variety of trading books, interdependencies between trading desks and departments, and a diverse data landscape can all provide difficulties to develop a streamlined process.

The development of a strong SWD plan and playbook can help to tackle these challenges. On top of that, a strong SWD plan also gives a more detailed insight into the activities conducted by the various trading desks as risks and returns of the different trading activities are analyzed. The clear trade-off between risk and return could therefore also be used for strategic decision-making such as:

- Operational efficiency: a more accurate understanding of cost and return may be achieved, as every desk is analyzed during the development of the SWD plan and playbook. This information could help management to remove operational inefficiencies.

- Generating liquidity: as banks are expected to analyze the impact on liquidity during the wind-down period they must also identify ways to cover any potential liquidity gaps. This knowledge may also be useful in case the bank needs to improve their liquidity position in a BaU situation.

- Reducing RWAs: banks are expected to analyze the impact on RWAs when winding-down their trading books. As a result, banks can use the results of the solvent wind-down analysis to strategically reduce their RWA, as the impact on RWA is readily available.

Zanders’ experience in SWD

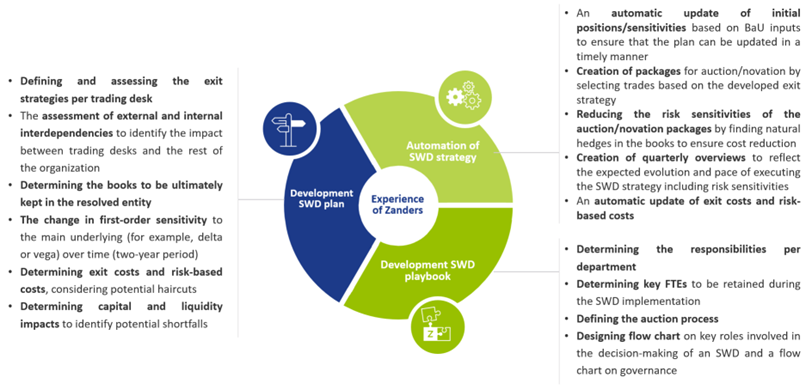

In the course of 2022, Zanders successfully helped one of the Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) with the development of a SWD plan and SWD playbook. After working on the day-one requirements, extensive time and effort was spent on optimizing the wind-down process to meet the steady-state requirements. Our support was provided on the points shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Support provided by Zanders on SWD of trading books.

With our experience across all aspects of the solvent wind-down requirements, we can help you to comply with this regulation. For questions or more information on solvent wind-downs, do not hesitate to contact Jaap Stolp or Ilse Schepers via +31 88 991 02 00.

Footnotes

[1] Latest guidance on SWD of trading books published by the SRB: 2021-12-01_Solvent-wind-down-guidance-for-banks.pdf (europa.eu)

[2] The seven dimensions for assessing resolvability include governance, loss absorbing and recapitalization capacity, liquidity and funding in resolution, operational continuity and access to Financial Market Infrastructure (FMI) services, information systems and data requirements, communication, and separability and restructuring. These dimensions describe the steps banks are expected to take to become resolvable.

[3] The Expectations for Banks by the SRB: EXPECTATIONS FOR BANKS (europa.eu)

[4] The SRB will define banks with material trading books based on, for example, exposures and the complexity of the books.

[5] The SRB encourages banks to provide information on a granular level. Banks should aim for the desk level. However, banks are also allowed to apply a different segmentation if this is more appropriate. For example, a business unit level is allowed if banks have their own internal segmentation of activities.

[6] Discussion paper of the FSB on Solvent Wind-down of Derivatives and Trading Portfolios: Solvent Wind-down of Derivatives and Trading Portfolios: Discussion Paper for Public Consultation (fsb.org). The FSB is established to coordinate at the international level the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies in order to develop and promote the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies.

[7] Under IFRS13 accounting standards, a ‘fair value hierarchy’ is used for defining the fair value of positions. Fair value measurements are categorized as level 3 of the fair value measurements are categorized as level 3 of the fair value hierarchy if the inputs are unobservable (for example due to low market activity).

Why an ESG rating is like drowning

Liquidity planning in SAP Analytics Cloud (SAC) is quite likely SAP’s response to the modernization of Cash Flow Forecasting (CFF) in Corporate Treasury, a key area in today’s treasury trends.

A 19th century book on Indian proverbs1 contains a story about a man who went on a journey with his son:

“He came to a stream. As he was uncertain of its depth, he proceeded to sound it; and having discovered the depth to be variable, he struck an average. The average depth being what his son could ford, he ordered him, unhesitatingly, to walk through the stream, with the sad consequence that the boy […] drowned.”

Averages can be useful metrics if you want to understand the changes over time in a certain population or data set, like housing prices, consumer confidence, or the indebtedness of corporates. The above story, however, shows – in a rather harsh way – that an average isn’t always the best metric to go by. The increasing use of ESG ratings2 seems to suggest that this lesson is not sufficiently understood.

In recent years, sustainability has taken center stage in the financial sector. Triggered by (among others) the European Commission’s Green Deal, to fight the threats from climate change and environmental degradation, in November 2020, the European Central Bank published clear expectations on the way banks should manage climate-related and environmental risks. Another example is the introduction of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) that requires banks and asset managers to disclose information on how they integrate sustainability risks and potential adverse sustainability impacts in their investment process.

To put these new expectations and regulations into practice, extensive use is being made of ESG ratings. These aim to measure the performance of a company on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) aspects; a bit like how credit ratings measure a company’s Probability of Default (PD). Stemming from the breadth of ESG topics, the number of indicators underlying an ESG rating typically dwarfs the number of indicators used to determine credit ratings. More than 100 indicators is not exceptional. These can range from environmental indicators like the company’s level of greenhouse gas emissions, water usage, and pollution, to social and governance indicators like the number of accidents in the workplace, the use of child labor, and the presence of anti-corruption policies. Not surprisingly, academic literature shows that ESG ratings differ considerably between rating providers.3

In practice, an ESG rating often is the (weighted) average of all individual indicators. This may not give the best indication of the ‘depth of the river’: Tesla Inc. may score rather well on certain environmental aspects, being the frontrunner in electric vehicles. From a social and governance perspective, however, it may not be considered best-in-class. Consequently, averaging the scores over the E, S, and G pillars does not lead to a proper understanding of the sustainability risks involved in this company. Or think of it this way: is child labor (negative score) less of a problem if a company’s employees enjoy freedom of association (positive score)?4

The issue also surfaces within the three ESG pillars as a wide range of indicators will be considered to determine a company’s performance for any of the three pillars. As an example, a Kuwait-based oil drilling company will likely score not so well on greenhouse gas emissions, but may obtain a good score on deforestation (given the lack of trees in the desert to begin with). Again, blindly averaging all environmental indicators will not lead to a very useful metric for the environmental performance of the company, nor will it help understanding to what climate risks a company is exposed to.

To truly understand a company’s sustainability risk profile, it is therefore important to assess all (material) indicators individually. Only in this way it is possible to properly address the multifaceted nature of ESG. Those who use only the aggregated ESG rating risk drowning.

Footnotes: