The adoption of ISO 20022 XML standards significantly enhances invoice reconciliation and operational efficiency, improving working capital management and Days Sales Outstanding (DSO).

Whether a corporate operates through a decentralized model, shared service center or even global business services model, identifying which invoices a customer has paid and in some cases, a more basic "who has actually paid me" creates a drag on operational efficiency. Given the increased focus on working capital efficiencies, accelerating cash application will improve DSO (Days Sales Outstanding) which is a key contributor to working capital. As the industry adoption of ISO 20022 XML continues to build momentum, Zanders experts Eliane Eysackers and Mark Sutton provide some valuable insights around why the latest industry adopted version of XML from the 2019 ISO standards maintenance release presents a real opportunity to drive operational and financial efficiencies around the reconciliation domain.

A quick recap on the current A/R reconciliation challenges

Whilst the objective will always be 100% straight-through reconciliation (STR), the account reconciliation challenges fall into four distinct areas:

1. Data Quality

- Partial payment of invoices.

- Single consolidated payment covering multiple invoices.

- Truncated information during the end to end payment processing.

- Separate remittance information (typically PDF advice via email).

2. In-country Payment Practices and Payment Methods

- Available information supported through the in-country clearing systems.

- Different local clearing systems – not all countries offer a direct debit capability.

- Local market practice around preferred collection methods (for example the Boleto in Brazil).

- ‘Culture’ – some countries are less comfortable with the concept of direct debit collections and want full control to remain with the customer when it comes to making a payment.

3. Statement File Format

- Limitations associated with some statement reporting formats – for example the Swift MT940 has approximately 20 data fields compared to the ISO XML camt.053 bank statement which contains almost 1,600 xml tags.

- Partner bank capability limitations in terms of the supported statement formats and how the actual bank statements are generated. For example, some banks still create a camt.053 statement using the MT940 as the data source. This means the corporates receives an xml MT940!

- Market practice as most companies have historically used the Swift MT940 bank statement for reconciliation purposes, but this legacy Swift MT first mindset is now being challenged with the broader industry migration to ISO 20022 XML messaging.

4. Technology & Operations

- Systems limitations on the corporate side which prevent the ERP or TMS consuming a camt.053 bank statement.

- Limited system level capabilities around auto-matching rules based logic.

- Dependency on limited IT resources and budget pressures for customization.

- No global standardized system landscape and operational processes.

How can ISO20022 XML bank statements help accelerate and elevate reconciliation performance?

At a high level, the benefits of ISO 20022 XML financial statement messaging can be boiled down into the richness of data that can be supported through the ISO 20022 XML messages. You have a very rich data structure, so each data point should have its own unique xml field. This covers not only more structured information around the actual payment remittance details, but also enhanced data which enables a higher degree of STR, in addition to the opportunity for improved reporting, analysis and importantly, risk management.

Enhanced Data

- Structured remittance information covering invoice numbers, amounts and dates provides the opportunity to automate and accelerate the cash application process, removing the friction around manual reconciliations and reducing exceptions through improved end to end data quality.

- Additionally, the latest camt.053 bank statement includes a series of key references that can be supported from the originator generated end to end reference, to the Swift GPI reference and partner bank reference.

- Richer FX related data covering source and target currencies as well as applied FX rates and associated contract IDs. These values can be mapped into the ERP/TMS system to automatically calculate any realised gain/loss on the transaction which removes the need for manual reconciliation.

- Fees and charges are reported separately, combined a rich and very granular BTC (Bank Transaction Code) code list which allows for automated posting to the correct internal G/L account.

- Enhanced related party information which is essential when dealing with organizations that operate an OBO (on-behalf-of) model. This additional transparency ensures the ultimate party is visible which allows for the acceleration through auto-matching.

- The intraday (camt.052) provides an acceleration of this enhanced data that will enable both the automation and acceleration of reconciliation processes, thereby reducing manual effort. Treasury will witness a reduction in credit risk exposure through the accelerated clearance of payments, allowing the company to release goods from warehouses sooner. This improves customer satisfaction and also optimizes inventory management. Furthermore, the intraday updates will enable efficient management of cash positions and forecasts, leading to better overall liquidity management.

Enhanced Risk Management

- The full structured information will help support a more effective and efficient compliance, risk management and increasing regulatory process. The inclusion of the LEI helps identify the parent entity. Unique transaction IDs enable the auto-matching with the original hedging contract ID in addition to credit facilities (letters of credit/bank guarantees).

In Summary

The ISO 20022 camt.053 bank statement and camt.052 intraday statement provide a clear opportunity to redefine best in class reconciliation processes. Whilst the camt.053.001.02 has been around since 2009, corporate adoption has not matched the scale of the associated pain.001.001.03 payment message. This is down to a combination of bank and system capabilities, but it would also be relevant to point out the above benefits have not materialised due to the heavy use of unstructured data within the camt.053.001.02 message version.

The new camt.053.001.08 statement message contains enhanced structured data options, which when combined with the CGI-MP (Common Global Implementation – Market Practice) Group implementation guidelines, provide a much greater opportunity to accelerate and elevate the reconciliation process. This is linked to the recommended prescriptive approach around a structured data first model from the banking community.

Finally, linked to the current Swift MT-MX migration, there is now agreement that up to 9,000 characters can be provided as payment remittance information. These 9,000 characters must be contained within the structured remittance information block subject to bilateral agreement within the cross border messaging space. Considering the corporate digital transformation agenda – to truly harness the power of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technology – data – specifically structured data, will be the fuel that powers AI. It’s important to recognize that ISO 20022 XML will be an enabler delivering on the technologies potential to deliver both predictive and prescriptive analytics. This technology will be a real game-changer for corporate treasury not only addressing a number of existing and longstanding pain-points but also redefining what is possible.

Entities must consider numerous factors when transitioning to the new DRM model, it is crucial for entities to develop a clear implementation plan.

The final article from Zanders on the DRM model presents the lifecycle of the DRM model over a single hedge accounting period and the prospective and retrospective assessments that are required to be carried out to ensure that the entity is correctly mitigating its interest rate risk for the assets/liabilities designated for the Current Net Open Risk Position (CNOP). The cycle will be illustrated by Scenario 1C taken from Agenda Paper 4A – May 20231. This is a relatively simple example, more complex ones can be found within the staff paper.

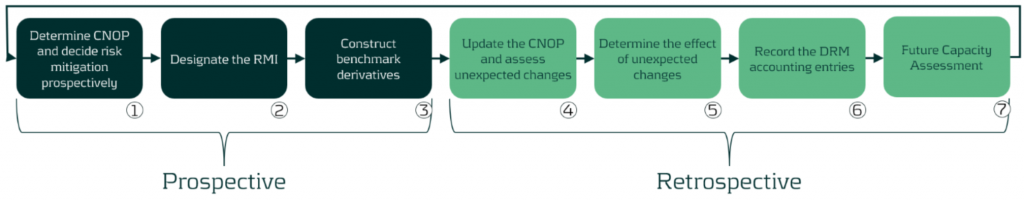

Figure 1: DRM Cycle

Prospective (start of the hedge accounting period)

The first three steps are related to the prospective assessment in the DRM model cycle.

The use of the prospective assessment is to ensure that the model is being used to mitigate interest rate risk and achieve the target profile that is set out in the RMS. The RMS should include the following:

- The risk mitigation cannot create new risks

- The RMI has to transform the CNOP position to a residual risk position that sits within the target profile (TP)

Step 1: The entity decides on the securities to be hedged and calculates the net open risk position (from an outstanding notional perspective) per time bucket.

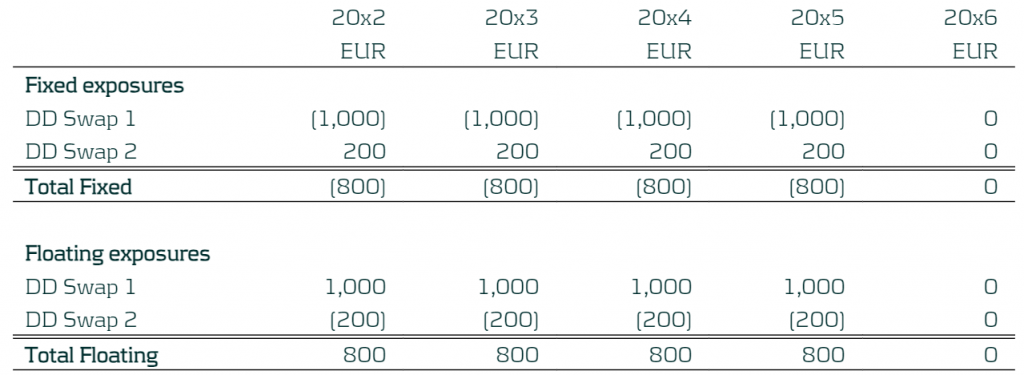

In the example below the company has floating and fixed exposures. The business in this case has a five-year fixed mortgage starting in 20x2 which is fully funded by a five-year floating rate liability. The focus period is 20x2 (start of the hedge accounting period) to 20x3 (end of the hedge accounting period) and so the first period 20x1 has been removed. The entity manages its entity-level interest rate risk for a 5-year time horizon, based on notional exposure in ∆NII and has decided to set the TP to be +/-EUR 500 in each of the repricing periods. Below we present the total fixed and total floating exposures from the product defined above). The individual breakdown of the fixed and floating is not required as each exposure is hedged as a total. The exposure are positions at year end.

Table 1: CNOP of the Entity with yearly buckets

Step 2: The entity will calculate the RMI based on the designated derivatives. The entity decided to mitigate 80% of the risk through the use of the following derivatives (existing and new). Please note that is a combination of derivatives from all the derivatives available in the books:

- A 5-year pay fixed receive floating IR swap with notional of EUR 1,000, traded on 1st January 20x1 (DD Swap 1) (existing deal).

- A 4-year receive fixed pay floating IR swap with notional of EUR 200, traded on 1st January 20x2 (DD Swap 2)

This leads to the designated derivatives with the following exposures:

Table: Exposures of the Designated Derivatives

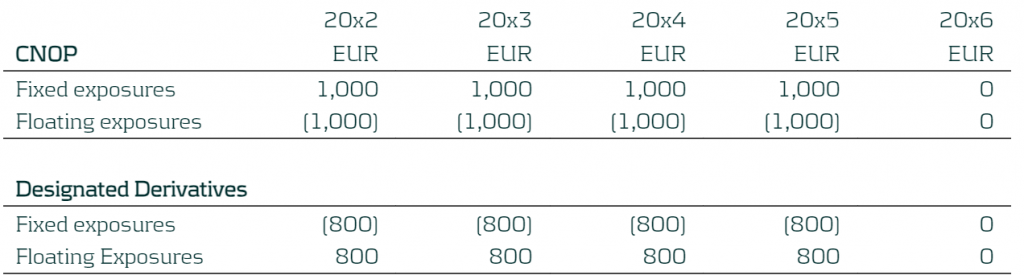

The exposures of the designated derivatives can then be compared to the CNOP as shown below:

Table 2: Exposures of the CNOP and Designated Derivatives

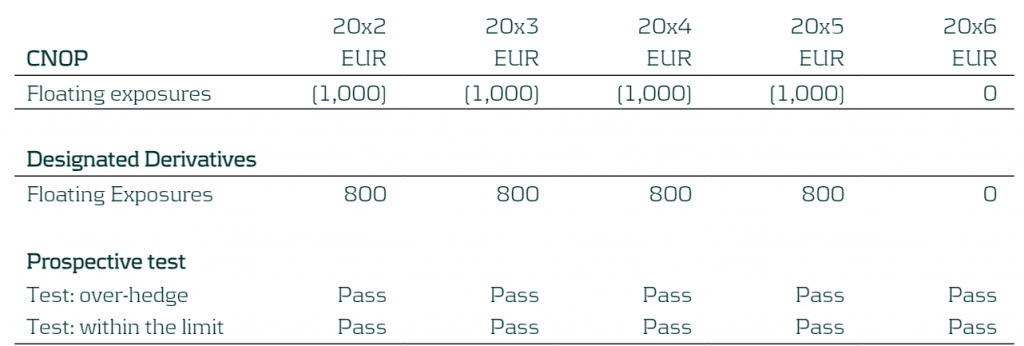

As the entity manages its interest rate risk based on ∆NII, the RMI focuses on the floating exposure.

The prospective test is performed by comparing the CNOP and Designated Derivatives exposures at each time bucket to see whether this moves the residual risk inside the TP (+/- EUR 500) set out within the RMS and not providing an over-hedge position. In this case the residual risk will be 0 (80% of CNOP versus DD exposures) and so the prospective assessments pass for all the time buckets.

Table 3: Prospective test

Step 3: Benchmark derivatives (hypothetical derivatives) are constructed based on the RMI calculated above.

Table 4: Benchmark Derivatives created for the Fixed and Floating Exposures

Retrospective (end of the hedge accounting period)

The following steps are related to the retrospective assessment of the DRM model.

The IASB requires a retrospective assessment, to check that risks have been mitigated, as well as a future capacity assessment for each period2. This is to ensure the company is correctly mitigating its interest rate risk, ensuring the CNOP sits within their TP and to quantify the potential misalignment arising from unexpected changes (during the hedge accounting period).

Step 4: The entity updates the CNOP with the latest ALM information (note that new business is excluded from the updated CNOP).

In this example, the financial asset was repaid fully at the end of 20x5. The revised expectation is that it will be partially repaid per end 20x4 and the rest repaid end 20x5.

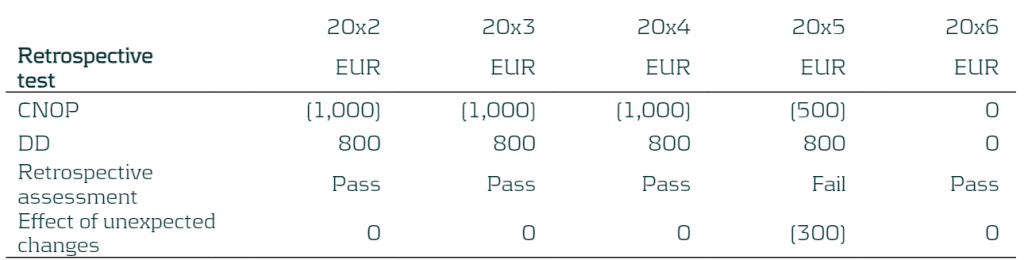

Table 5: Updated CNOP

Step 5: The potential misalignment due to unexpected changes is calculated. The new CNOP is compared to the RMI that was set in Step 2. Misalignments can occur due to:

- Difference in changes in the fair value of the designated derivatives and benchmark derivatives (i.e: different fixed rate, fair value adjustments)

- The effect of the unexpected changes in the current net open position during the period

Table 6: Updated CNOP

Table 7: Determining the effect of unexpected changes

If there are misalignments and the entity breaches the retrospective assessment, meaning that it has been over-mitigating its risk, the benchmark derivatives will need to be revised. One way in which this can be achieved is through the creation of additional benchmark derivatives which can represent the misalignment occurring. These will be based on the prevailing benchmark interest rates.

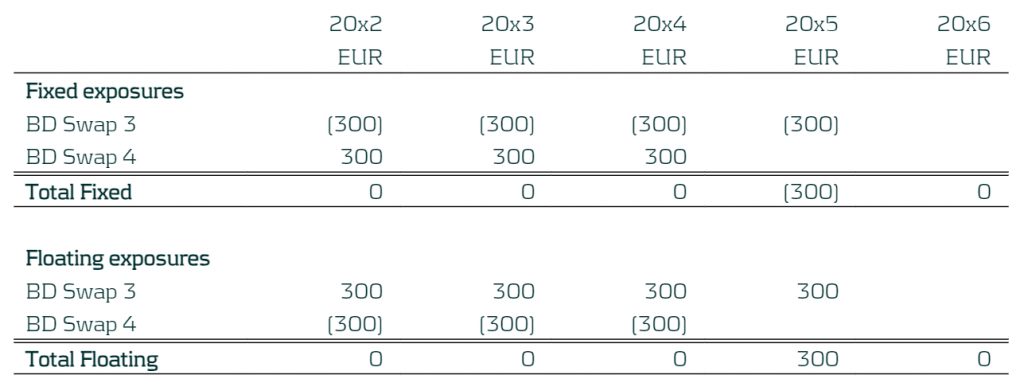

Therefore, for this example, the entity will construct two additional benchmark derivatives to represent these changes:

- A 4-year pay fixed rate receive floating IR swap with notional of EUR 300, maturing on the 31st December 20x5 (BD Swap 3)

- A 3-year receive fixed pay floating IR swap with notional of EUR 300, maturing on 31st December 20x4 (BD Swap 4)

Table 8: Additional Benchmark Derivatives

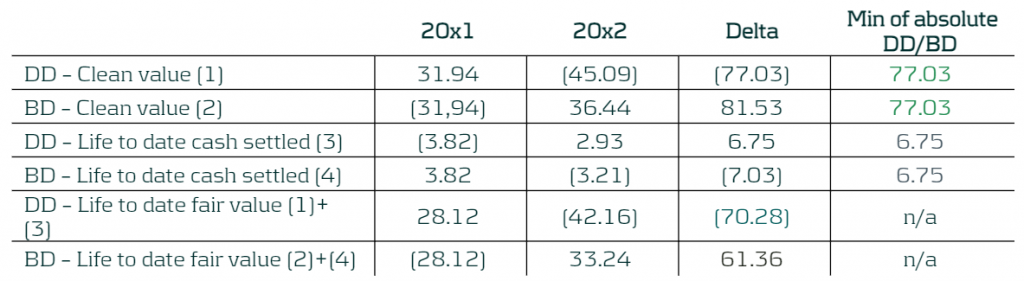

Step 6: The hedge accounting adjustments are calculated, and the DRM model outputs are required to be booked3:

- a) The designated derivatives to be measured at fair value in the statement of financial position.

- b) The DRM adjustments to be recognised in the statement of financial position, as the lower of (in absolute amounts):

- The cumulative gain or loss on the designated derivatives from the inception of the DRM model.

- The cumulative change in the fair value of the risk mitigation intention attributable to repricing risk from the inception of the DRM model. This would be calculated using the benchmark derivatives (from step 3 and step 5) as a proxy.

- c) The net gain or loss from the designated derivatives calculated in accordance with (a) and the DRM adjustment calculated in accordance with (b) would be recognised in the statement of profit or loss.

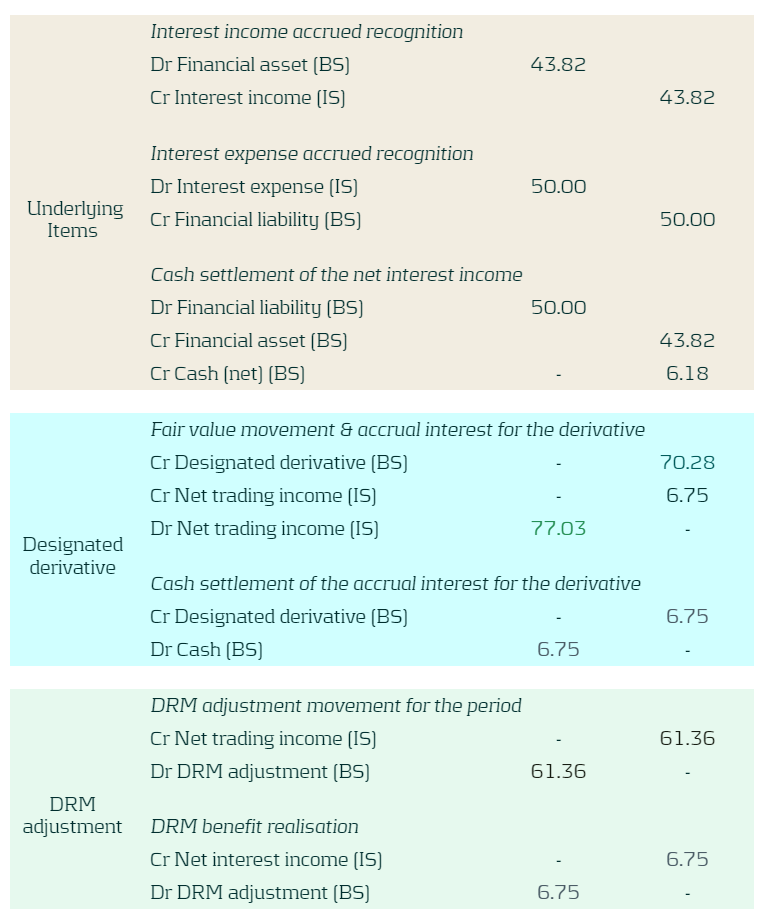

The table below presents the EUR booking figures for this example. Figures are for the period 20x2 to 20x3.

The underlying items block represents the interest rate paid/received for the financial asset and financial liability for the period.

The designated derivative block presents the fair value movement of the designated derivatives for the period and the realised cash flow (net interest rate paid or received) on these instruments (trading income).

The DRM adjustment block presents the fair value movement of the benchmark derivatives for the period and the realised cash flow on these instruments (trading income).

BS represents a balance sheet account when IS represents an income statement account.

Table 9: Booking figures

Table 10: Booking figures calculation

Step 7: The last step is the future capacity assessment which was introduced by the IASB in February 2023 and is still under development so the final implementation of this is still to be released. This step is used to replace the previous retrospective assessment that compared the CNOP sensitivity to the TP. The IASB have yet to release more information on the methodology. The example shown does not assume that the future capacity assessment is carried out.

What Next?

The IASB plans to publish an exposure draft by 2025 and so companies start thinking about their process for onboarding the DRM model in their accounting process. The DRM model introduces a range of changes to the hedge accounting framework and the transition process will not be an easy switch. Therefore, companies need to ensure that they have a clear and concise implementation plan to ensure a smooth transition. Involvement from stakeholders from across the company such as (IT, Front Office, Risk, Accounting, Treasury) is required to ensure the project is implemented correctly and in time.

What can Zanders offer?

Transitioning to the new DRM model can be difficult due to the dynamic nature of the model, especially with a more complex balance sheet. Zanders can provide a wide range of expertise to support in the onboarding of the DRM model into your company’s hedging and accounting. We have supported various clients with hedge accounting– including impact analyses, derivative pricing and model validation, and are familiar with the underlying challenges. Zanders can manage the whole project lifecycle from strategizing the implementation, alignment with key stakeholders and then helping design and implement the required models to successfully carry out the hedge accounting at every valuation period.

For further information, please contact Pierre Wernert, or Alexander Oldroyd.

Read our other blogs and learn more on Rethinking Macro Hedging: Introduction to DRM, and Rethinking Macro Hedging: What are the Key Components of the DRM Model?

Citations

- Agenda Paper 4A ↩︎

- The capacity, introduced in Staff Paper 4B – February 2023, assessment is still subject to further development. ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4A – May 2022 ↩︎

The Swift MT-MX migration and global industry adoption of ISO 20022 XML are more than just a simple compliance change.

The corporate treasury agenda continues to focus on cash visibility, liquidity centralization, bank/bank account rationalization, and finally digitization to enable greater operational and financial efficiencies. Digital transformation within corporate treasury is a must have, not a nice to have and with technology continuing to evolve, the potential opportunities to both accelerate and elevate performance has just been taken to the next level with ISO 20022 becoming the global language of payments. In this 6th article in the ISO 20022 XML series, Zanders experts Fernando Almansa, Eliane Eysackers and Mark Sutton provide some valuable insights around why this latest global industry move should now provide the motivation for corporate treasury to consider a cash management RFP (request for proposal) for its banking services.

Why Me and Why Now?

These are both very relevant important questions that corporate treasury should be considering in 2024, given the broader global payments industry migration to ISO 20022 XML messaging. This goes beyond the Swift MT-MX migration in the interbank space as an increasing number of in-country RTGS (real-time gross settlement) clearing systems are also adopting ISO 20022 XML messaging. Swift are currently estimating that by 2025, 80% of the domestic high value clearing RTGS volumes will be ISO 20022-based with all reserve currencies either live or having declared a live date. As more local market infrastructures migrate to XML messaging, there is the potential to provide richer and more structured information around the payment to accelerate and elevate compliance and reconciliation processes as well as achieving a more simplified and standardized strategic cash management operating model.

So to help determine if this really applies to you, the following questions should be considered around existing process friction points:

- Is your current multi-banking cash management architecture simplified and standardised?

- Is your account receivables process fully automated?

- Is your FX gain/loss calculations fully automated?

- Have you fully automated the G/L account posting?

- Do you have a standard ‘harmonized’ payments message that you send to all your banking partners?

If the answer is yes to all the above, then you are already following a best-in-class multi-banking cash management model. But if the answer is no, then it is worth reading the rest of this article as we now have a paradigm shift in the global payments landscape that presents a real opportunity to redefine best in class.

What is different about XML V09?

Whilst structurally, the XML V09 message only contains a handful of additional data points when compared with the earlier XML V03 message that was released back in 2009, the key difference is around the changing mindset from the CGI-MP (Common Global Implementation – Market Practice) Group1 which is recommending a more prescriptive approach to the banking community around adoption of its published implementation guidelines. The original objective of the CGI-MP was to remove the friction that existed in the multi-banking space as a result of the complexity, inefficiency, and cost of corporates having to support proprietary bank formats. The adoption of ISO 20022 provided the opportunity to simplify and standardize the multi-banking environment, with the added benefit of providing a more portable messaging structure. However, even with the work of the CGI-MP group, which produced and published implementation guidelines back in 2009, the corporate community has encountered a significant number of challenges as part of their adoption of this global financial messaging standard.

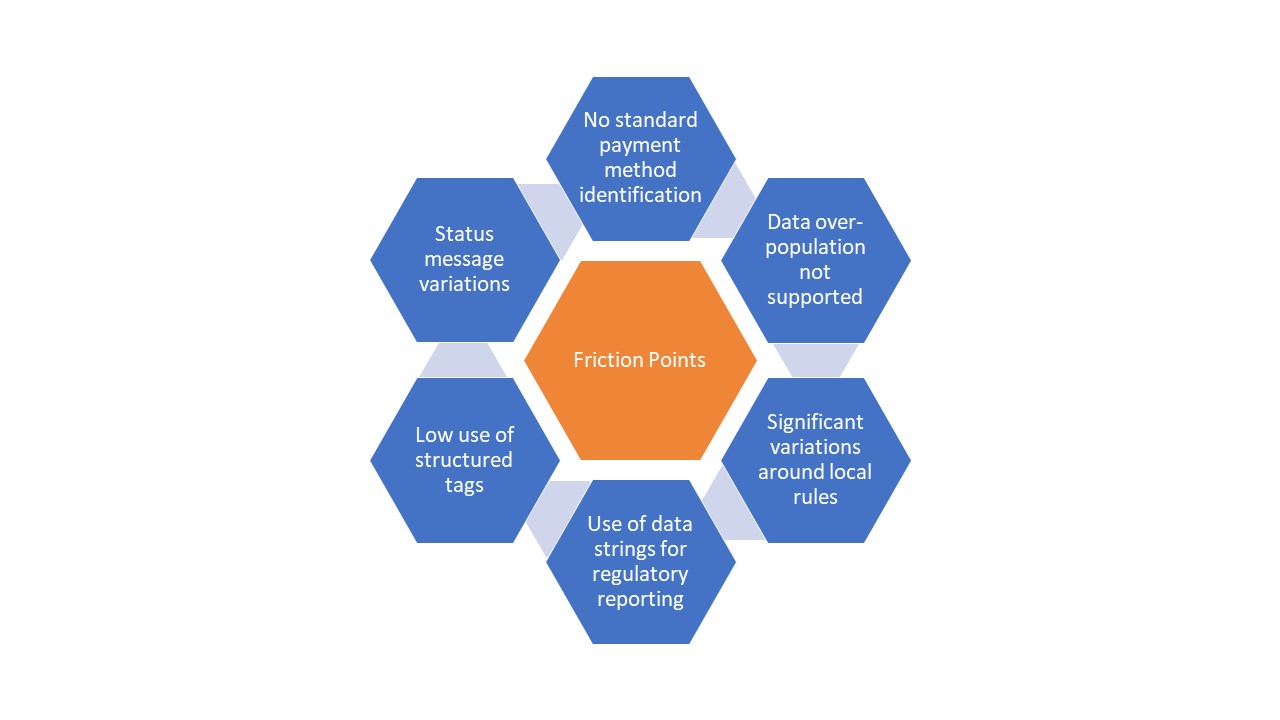

The key friction points are highlighted below:

Diagram 1: Key friction points encountered by the corporate community in adopting XML V03

The highlighted friction points have resulted in the corporate community achieving a sub-optimal cash management architecture. Significant divergence in terms of the banks’ implementation of this standard covers a number of aspects, from non-standard payment method codes and payment batching logic to proprietary requirements around regulatory reporting and customer identification. All of this translated into additional complexity, inefficiency, and cost on the corporate side.

However, XML V09 offers a real opportunity to simplify, standardise, accelerate and elevate cash management performance where the banking community embraces the CGI-MP recommended ‘more prescriptive approach’ that will help deliver a win-win situation. This is more than just about a global standardised payment message, this is about the end to end cash management processes with a ‘structured data first’ mindset which will allow the corporate community to truly harness the power of technology.

What are the objectives of the RFP?

The RFP or RFI (request for information) process will provide the opportunity to understand the current mindset of your existing core cash management banking partners. Are they viewing the MT-MX migration as just a compliance exercise. Do they recognize the importance and benefits to the corporate community of embracing the recently published CGI-MP guidelines? Are they going to follow a structured data first model when it comes to statement reporting? Having a clearer view in how your current cash management banks are thinking around this important global change will help corporate treasury to make a more informed decision on potential future strategic cash management banking partners. More broadly, the RFP will provide an opportunity to ensure your core cash management banks have a strong strategic fit with your business across dimensions such as credit commitment, relationship support to your company and the industry you operate, access to senior management and ease of doing of business. Furthermore, you will be in a better position to achieve simplification and standardization of your banking providers through bank account rationalization combined with the removal of non-core partner banks from your current day to day banking operations.

In Summary

The Swift MT-MX migration and global industry adoption of ISO 20022 XML should be viewed as more than just a simple compliance change. This is about the opportunity to redefine a best in class cash management model that delivers operational and financial efficiencies and provides the foundation to truly harness the power of technology.

Citations

- Common Global Implementation–Market Practice (CGI-MP) provides a forum for financial institutions and non-financial institutions to progress various corporate-to-bank implementation topics on the use of ISO 20022 messages and to other related activities, in the payments domain. ↩︎

The Basel IV reforms, effective January 1, 2025, introduce significant changes to credit risk management.

The Basel IV reforms published in 2017 will enter into force on January 1, 2025, with a phase-in period of 5 years. These are probably the most important reforms banks will go through after the introduction of Basel II. The reforms introduce changes in many areas. In the area of credit risk, the key elements of the banking package include the revision of the standardized approach (SA), and the introduction of the output floor.

In this article, we will analyse in detail the recent updates made to real estate exposures and their impact on capital requirements and internal processes, with a particular focus on collateral valuation methods.

Real Estate Exposures

Lending for house purchases is an important business for banks. More than one-third of bank loans in the EU are collateralised with residential immovable property. The Basel IV reforms introduce a more risk-sensitive framework, featuring a more granular classification system.

Standardized Approach

The new reforms aim for banks to diminish the advantages gained from using the Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) model. All financial institutions that calculate capital requirements with the IRB approach are now required to concurrently use the standardized approach. Under the Standardized Approach, financial institutions have the option to choose from two methods for assigning risk weights: the whole-loan approach and the split-loan approach.

Collateral Valuation

A significant change introduced by the reforms concerns collateral valuation. Previously, the framework allowed banks to determine the value of their real estate collateral based on either the market value (MV) concept or the mortgage lending value (MLV) concept. The revised framework no longer differentiates between these two concepts and introduces new requirements for valuing real estate for lending purposes by establishing a new definition of value. This aims to mitigate the impact of cyclical effects on the valuation of property securing a loan and to maintain more stable capital requirements for mortgages. Implementing an independent valuation that adheres to prudent and conservative criteria can be challenging and may result in significant and disruptive changes in valuation practices.

Conclusion

To reduce the impact of cyclical effects on the valuation of property securing a loan and to keep capital requirements for mortgages more stable, the regulator has capped the valuation of the property, so that it cannot for any reason be higher than the one at origination, unless modifications to that property unequivocally increase its value. Regulators have high expectations for accounting for environmental and climate risks, which can influence property valuations in two ways. On the one hand, these risks can trigger a decrease in property value. On the other hand, they can enhance value, as modifications that improve a property's energy performance or resilience to physical risks - such as protection and adaptation measures for buildings and housing units - may be considered value-increasing factors.

Where Zanders can help

Based on our experience, we specialize in assisting financial institutions with various aspects of Basel IV reforms, including addressing challenges such as limited data availability, implementing new modeling approaches, and providing guidance on interpreting regulatory requirements.

For further information, please contact Marco Zamboni.

“Treasury is a small universe in the US, so getting traction is a key challenge – but once we do, it will catch fire”

Dan Delean recently joined Zanders as Managing Director of our newly formed US risk advisory practice. With a treasury career spanning more than 30 years, including 15 years specializing in risk advisory, he comes to us with an impressive track record of building high performing Big 4 practices. As Dan will be spearheading the growth of Zanders’ risk advisory capabilities in the US, we asked him to share his vision for our future in the region.

Q. What excites you the most about leading Zanders' entry into the US market for risk advisory services?

Dan: This is a chance to build a world-class risk advisory practice in the US. Under the leadership of Paul DeCrane, the quality of Zanders reputation in the US has already been firmly established and I’m excited to build on this. I love to build – teams, solutions, physical building – and I am unnaturally passionate about treasury. Treasury is a small universe here, so getting traction is a key challenge – but once we do, it will catch fire.

Q. What do you see as the unique challenges (or opportunities) for Zanders in the US market?

Dan: A key concern for financial institutions in the US right now is the low availability of highly competent treasury professionals. Rising interest rates, combined with economic and political uncertainty, are driving up demand for deeper treasury insights in the US. In particular, the regulatory regime here is increasing its focus on liquidity and funding challenges, with a number of banking organizations on the ‘list’ for closing. But while the need for deep treasury competencies is growing fast, the pool of talent can’t keep up with this demand. This is an expertise gap Zanders is perfectly placed to address.

Q. How do you plan to tailor Zanders' risk advisory services to meet the specific needs and expectations of US clients?

Dan: My plan is to attract the best talent available, building a team with the capability to work with clients to tackle the hardest problems in the market. I want to build a recognized risk advisory team, that’s trusted by clients with difficult challenges. My intention is to focus on building these competencies through a highly focused approach to teaming.

Q. In what ways do you believe Zanders' approach to risk advisory services sets it apart from other firms in the US market?

Dan: Focus on competencies and effective teaming will make Zanders stand out among advisory businesses in the US. Zanders is an expert-driven, competency focused practice, with a large team of seasoned treasury and risk professionals and a willingness to team up with other industry players. This approach is not common in the US. Most firms here deploy leverage models or are highly technical.

Q. What kind of culture or working environment do you aim to foster within the US branch of Zanders?

Dan: I’m committed to recruiting well, training even better, and being a key supporter of my team. I believe culture starts at the top, so all team members that join or work with us need to buy into the expert model and Zanders’ approach to advisory. Within this culture, trust and accountability will always be core tenets – these will be central to my approach to teaming.

With his value-driven, competency-led approach to teaming and practice development, there’s no-one better qualified than Dan to lead the growth of our US risk advisory. To learn more about Zanders and what makes us different, please visit our About Zanders page.

Insurance Treasury is evolving into Treasury 4.x, a forward-thinking paradigm integrating advanced technology and strategic foresight to enhance efficiency and resilience in the digital era.

The productivity and performance of the treasury function within insurance companies have undergone a transformative evolution, driven by the emergence of what is now termed Treasury 4.x. In this digital era, characterized by rapid technological advancements, Insurance Treasury is transitioning towards a more dynamic and strategic role. Treasury 4.x is distinguished by its capacity to envision and operate within various financial scenarios, reflecting a forward-thinking approach. The contemporary Insurance Treasury aligns itself with the principles of "Fit-for-purpose" – emphasizing a centralized organizational structure embedded seamlessly within the financial supply chain. Highly automated processes, often referred to as "exception-based management," are integral to this paradigm shift, enabling treasuries to focus resources on critical issues and exceptions, thereby enhancing efficiency and minimizing manual intervention. This evolution underscores the imperative for insurance treasuries to leverage cutting-edge technologies and embrace a proactive, scenario-driven mindset, ensuring adaptability and resilience in the face of dynamic market conditions.

Innovation of Payment Landscape

In the ever-evolving landscape of payment innovation within the treasury functions of insurance companies, a pivotal focus has been placed on migrating to the ISO 20022 XML messaging standard and moving away from FIN MT messages. This migration, driven by SWIFT, is not just a strategic choice but an industry-wide mandate, compelling all financial institutions, including insurance companies, to transition to the ISO standard by November 2025. This migration is a cornerstone in revolutionizing payment processes, offering a standardized and enriched data format that not only enhances interoperability but also facilitates more robust and information-rich communication. As insurance companies navigate this time-sensitive transition, a review of address logic within payment files becomes even more critical. The insurance companies are mandated to review and refine address logic within payment files by November 2026. Ensuring that the company is compliant with evolving financial messaging standards will not only improve the overall efficiency, speed and compliance of payments, but it will also provide the opportunity to redefine the best-in-class cash management operating model.

In additional to the industry migration to a new messaging standard, the introduction of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) could impact the traditional roles of treasuries by offering new means of payment, settlement, and potentially altering liquidity management strategies. CBDCs could enhance efficiency in cross-border transactions, simplify reconciliation processes, and influence investment strategies. Insurance treasuries might need to adapt their systems and processes to incorporate CBDCs effectively, ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements and taking advantage of potential benefits associated with this digital form of currency. We are also witnessing an increase in momentum around the use of distributed ledger technology within the wholesale banking domain. In December, JP Morgan announced it was live on Partior, the Singapore-based interbank payment network that uses blockchain and is designed as a multi-bank, multi-currency system for wholesale use, with each bank controlling its own node. This is clear evidence we are starting to gain real traction around potential solutions using both blockchain and CBDC’s that will further increase the number of payment rails available to support the payments ecosystem.

Finally, the payment landscape of insurance companies sees further innovation with Faster Claims Payment (FCP). This solution streamlines the disbursement of claims, decoupling it from traditional monthly processes. FCP integrates seamlessly with the Vitesse payment platform, ensuring direct access to insurer funds and significantly reducing delays in payments. This paradigm shift promotes efficiency and enhances customer satisfaction through its accelerated claims payment system. The innovative payment landscape, however, could highlight a potential impact for processes of insurance treasuries. Increased application of faster and real-time payments requires insurance treasuries to have sufficient liquidity readily available to meet the immediate financial obligations. This demands careful planning of cash reserves to ensure uninterrupted claim processing while maintaining financial stability and stresses the importance of effective cash management for navigating any potential downside impact of FCP.

Changing Macroeconomic Environment

The insurance treasury is profoundly influenced by macroeconomic events, and the convergence of several geopolitical challenges has introduced heightened uncertainty and downside risks. Elevated geopolitical tensions, particularly the intensified strategic rivalry between the United States and China, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the recent Middle East conflict, pose significant threats to the insurance industry's stability. These events bring the potential for energy price shocks, amplifying concerns about increased insurance industry losses stemming from geopolitical and economic upheavals. Furthermore, the scheduled elections in 76 countries, with pivotal ones in the United States, Taiwan, and India, add an additional layer of uncertainty. Political transitions can introduce policy shifts, impacting regulatory environments and potentially altering economic landscapes, further complicating risk assessment for insurance treasuries. As the global geopolitical landscape remains dynamic, insurance treasuries must navigate these challenges prudently, emphasizing resilience and adaptability in their financial strategies to mitigate potential adverse impacts.

Interest rate changes command a substantial impact on the treasury functions of insurance companies, and the recent shifts in central bank policies have introduced a dynamic landscape. The conclusion of the central banks' rate tightening cycle, coupled with the Federal Reserve's announcement of rate cuts for 2024 and beyond, signals a pivotal change. While these rate cuts are aimed at supporting economic recovery, they pose challenges for insurance treasuries that traditionally benefit from higher interest rates. The insurance industry faces the paradox of modest GDP growth across advanced economies, with the downside risk of a potential rebound in inflation and further geopolitical shocks. The relatively elevated interest rates, however, offer a silver lining for (re)insurers, providing a boost to future recurring income. As maturing assets are reinvested at higher rates, this strategic advantage could help mitigate some of the challenges posed by the shifting interest rate environment, fostering resilience and adaptability in the treasury functions of insurance companies.

Taking into account the aforementioned macroeconomic changes, insurance treasuries must ensure they possess local treasury experts capable of supporting multiple regions with adapting to shifting business dynamics.

Changing Market Rates

The impact of changing market rates on the asset management activities of insurers is profound, extending to collateral management practices. Market rate fluctuations exert direct influence on the valuation and performance of their investment portfolios, notably affecting the required Variation Margin (VR) and Uncleared Margin Rules (UMR) on derivatives holdings. As rates oscillate, the value of derivative positions can vary significantly, necessitating adjustments in margin requirements to effectively manage risk exposures and collateral obligations.

Additionally, these changes in market rates affect the liquidity position of insurers, prompting the need for more dynamic models to optimize liquidity management. Given the importance of maintaining sufficient cash and liquid assets, insurers must adapt their strategies to ensure they can meet obligations promptly, especially considering the impact of FX fluctuations on assets denominated in non-base currencies. This entails employing more dynamic models to gauge liquidity needs accurately and employing strategies such as RePo agreements to enhance flexibility in accessing cash when required. Thus, navigating the complexities of changing market rates requires insurers to employ a comprehensive approach that integrates risk management, liquidity optimization, and currency hedging strategies.

Data Analytics and Predictive Modeling

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and predictive analytics has revolutionized the treasury function within insurance companies, particularly in the realm of cash flow forecasting. These advanced technologies enable insurance treasuries to analyze vast datasets, identify patterns, and make more accurate predictions regarding future cash flows. AI algorithms can process information rapidly, taking into account a multitude of variables, such as market trends, policyholder behavior, and economic indicators. This enhanced predictive capability is instrumental in optimizing liquidity management, allowing insurance companies to proactively anticipate cash needs and allocate resources efficiently. The importance of AI and predictive analytics in cash flow forecasting cannot be overstated, as it empowers treasuries to make informed decisions, mitigate financial risks, and navigate the complexities of the insurance landscape with greater precision and agility.

Regulatory Compliance

Regulatory compliance is pivotal for insurance company treasuries, significantly influencing financial strategies and operations. The complex regulatory landscape, including directives like the Insurance Recovery and Resolution Directive, Solvency II, and EMIR Refit, aims at ensuring financial stability, consumer protection, and market integrity. These requirements, from solvency standards to reporting obligations, impact how treasuries manage assets, liabilities, and capital. Non-compliance can lead to severe consequences, prompting insurance treasuries to invest in sophisticated systems for continuous monitoring. Striking a balance between compliance and strategic financial goals is crucial for navigating the regulatory environment and ensuring long-term organizational sustainability.

Additionally, insurance companies operating across different jurisdictions face fragmented compliance regulations, consisting of local laws and regulations. This has become a prominent challenge experienced by insurance company treasuries and visible in various treasury processes, from payments to liquidity management. Establishing robust processes and conducting regular compliance reviews could help insurance companies to address the fragmented compliance framework. By proactively addressing compliance challenges and embracing innovative solutions, insurance companies could achieve robust global operations and success in an increasingly interconnected world.

For more information about Treasury 4.x, download our latest whitepaper: Treasury 4.x - The age of productivity, performance and steering.

The aim of the DRM model is to tie together hedge accounting with risk management strategy so that an entity’s effort to mitigate interest rate risk is better reflected within their financial statement.

In the second instalment of the Zanders series on the DRM model, the Risk Management Strategy (“RMS”) and the DRM process are introduced and with it the new concepts that the IASB have established. The RMS sets out how an entity will manage its interest rate risk, which is the basis of every other part of the DRM model. The IASB has laid out the following expectations for a company’s RMS1:

- Process to approve and amend RMS

- Risk management levels and scope of assets and liabilities

- Risk metrics used

- Range of acceptable risk limits (i.e. the target profile)

- Risk aggregation method and risk management time horizon

- Methodologies to estimate expected cash flows and/or core demand deposits.

Changes to the RMS that result in a change in the target profile (“TP”), lead to a discontinuation of the hedge2. The IASB will further deliberate on when the discontinuation occurs and whether such changes lead to discontinuation of the model at a future date3.

The overall aim of the model is to compare the target profile (“TP”) with the current net open positions (“CNOP”) and thereby produce a risk mitigation intention (“RMI”), which represents the amount of risk that the entity intends to mitigate through the use of designated derivatives. The IASB has tentatively decided that each separate currency should have its own DRM model.

Below a figure of the DRM process can be found that shows how the different components of the model relate to each other. In the following sections a detailed explanation will be provided for each of these elements.

Figure 1: DRM process

As part of the RMS the entity is required to define the target risk metric. The company cannot change this metric for each period and must stick to the metric specified within the RMS. However, the RMS can specify the use of a different metric over different future time horizons. E.g. the company’s RMS could be to stabilise NII for the first three years on notional exposure and then the present value using PV01 for the following years.

Current Net Open Position

The first step in implementing the model is to decide on the assets and liabilities that should be hedged through the DRM framework. The eligible assets and liabilities are currently:

- Financial assets or liabilities must be measured at amortised cost under IFRS 9

- Future transactions that result in financial assets or financial liabilities that are classified as subsequently measured at amortised cost under IFRS 9 ($4.2.1).

Furthermore, the IASB has imposed the following criteria on the eligible assets/liabilities that can be designated in the CNOP4, 5; an asset/liability is only eligible if all the criteria are met:

| No. | Eligibility criteria for the Assets/Liabilities as hedged items |

| 1 | The effect of credit risk does not dominate the changes in expected future cashflows. |

| 2 | Future transactions must be highly probable except in the case of transactions that are the reinvestment or refinancing of existing financial assets/liabilities6. |

| 3 | Items already designated in a hedge accounting relationship are not eligible. |

| 4 | Items must be managed on a portfolio basis for interest rate risk management purposes. |

Table 2: Criteria for Assets & Liabilities

An asset/liability is eligible for the CNOP if all the above criteria are met. The IASB has explored other eligible assets/liabilities and have concluded that assets/liabilities that are FVOCI7 are recommended to be eligible while the ones that are FVPL8 were not recommended to be eligible. Equity was deemed not to be eligible for designation in the CNOP. Since the DRM model is still under review, the eligible assets/liabilities could change before the draft is finalised. Therefore, we advise companies to stay up to date with the latest information.

Target Profile

The Target Profile (TP) is linked to a company’s RMS. It sets the risk limits on the CNOP, before risk mitigation actions can be initiated. When the company assesses the risk over different time buckets, it needs to be consistent with the company’s RMS. All of this should be clearly documented within the company’s RMS. The TP should be set at the time when the hedge relationship is designated. The company can also take action to mitigate risks even before the limits are breached. Stakeholders have raised concerns regarding the granularity for the TP. Therefore, the IASB will conduct further research in this area to identify a common principle to be used universally for the allocation of risk limits for the TP.9

Risk Mitigation Intention

The Risk Mitigation Intention (RMI) is a calculated metric based on the company's efforts, through the use of derivatives, to reduce its CNOP for each period to align with the TP outlined in the RMS. Once the RMI is set, it cannot be changed retrospectively. When an entity is deciding on its RMI the following should be considered10:

- The RMI cannot exceed the CNOP. When entities monitor their CNOP by time buckets, this must hold for any time bucket

- The RMI needs to transform the CNOP position to a residual risk position that sits within the TP

- The RMI needs to be evidenced by real actions taken such as the actual derivates traded in the market

Stakeholders have been concerned that they may not be able to faithfully mitigate the risk with market traded instruments due to liquidity. E.g. there may be little liquidity for a nine-year interest rate swap to hedge an asset that reprices in nine years in the CNOP. Therefore, the IASB has tentatively stated that an entity could use a 10-year swap for a 9-year hedge. Then in the model the RMI is set to be 0 for the 10th year and the benchmark derivative matures on the 9th year. Therefore, the misalignment due to the extra year for the designated derivative would be reported in the profit and loss11.

Designated Derivatives

Designated derivatives are the instruments that mitigate interest risk for the company. These are entered into with external counterparties. They are also used to evidence the RMI that a company is taking. The full list of designated derivatives has not been set, it is expected it will contain interest rate swaps (including basis swaps), forward starting swaps and forward rate agreements12. In Staff Paper 4C – July 2023, the AISB recommended that non-linear derivatives, except for net written options, are eligible as designated derivatives.

Benchmark Derivatives

Benchmark derivatives (BD) are based on the same concepts as IFRS 9’s hypothetical derivatives. These are used to measure the efficacy of the hedging. The benchmark derivatives are based on the following specified characteristics13:

- The benchmark derivative is constructed to be on-market at designation – i.e constructing a “hypothetical” derivative that is nil at zero, where the floating leg replicates the managed risk, and the fixed leg is calibrated to the yield curve. Note that benchmark derivatives are only constructed once and are therefore not reset at every period.

- A benchmark derivative cannot be used to include features in the value of the RMI that only exist in the designated derivative (but not the RMI) – This means that features from the designated derivative cannot be used in the benchmark derivative if they don’t exist in the RMI.

- The amount of risk and the tenor of the benchmark derivative is prescribed by the RMI and expressed in the risk metric (i.e. KPI) the entity manages at the repricing time period – E.g. if an company is using PV01 as the managed KPI, the amount of risk is measured as the sensitivity of one basis point shift in the managed yield curve.

Transitioning to the new DRM model can be difficult due to the dynamic nature of the model, especially with a more complex balance sheet. Zanders can provide a wide range of expertise to support in the onboarding of the DRM model into your company’s hedging and accounting. We have successfully supported various clients with hedge accounting– including impact analyses, derivative pricing and model validation, and are familiar with the underlying challenges. Zanders can manage the whole project lifecycle from strategizing the implementation, alignment with key stakeholders and then helping design and implement the required models to successfully carry out the hedge accounting at every valuation period. As the deadline is quickly approaching it would benefit entities to start assessing the key characteristics of the DRM model in order to understand how to change their current framework to the new one.

For further information, please contact Pierre Wernert, or Alexander Oldroyd.

Read our other blogs and learn more on Rethinking Macro Hedging: Introduction to DRM and The DRM Cycle: The Model in Action.

Citations

- IASB Webcast – October 2022 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4A – November 2021 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4A – April 2023 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4B – April 2018 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4A – February 2023 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4C – April 2023 ↩︎

- Fair Value through Other Comprehensive Income ↩︎

- Fair Value through Profit or Loss. ↩︎

- Staff Paper AP4 – July 2022 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4A – May 2022 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4B – April 2023 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4C – July 2023 ↩︎

- Staff Paper 4B – April 2023 ↩︎

An update on the new transfer pricing regulations

In January 2022, the OECD incorporated Chapter X to the latest edition of their Transfer Pricing Guidelines, a pivotal step in regulating financial transactions globally. This addition aimed to set a global standard for transfer pricing of intercompany financial transactions, an area long scrutinized for its potential for profit shifting and tax avoidance. In the years since, we have seen various jurisdictions explicitly incorporating these principles and providing further guidance in this area. Notably, in the last year, we saw new guidance in South Africa, Germany, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), while the Swiss and American tax authorities offered more explanations on this topic. In this article we will take you through the most important updates for the coming years.

Finding the right comparable

The arm's length principle established in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines stipulates that the price applied in any intra-group transaction should be as if the parties were independent.1 This principle applies equally to financial transactions: every intra-group loan, guarantee, and cash pool should be priced in a manner that would be reasonable for independent market participants. Chapter X of the OECD Guidelines provided for the first time a detailed guidance on applying the arm's length principle to financial transactions. Since its publication, achieving arm's length pricing for financial transactions has become a significant regulatory challenge for many multinational corporations. At the same time the increased interest rates have encouraged tax authorities to pay increased attention to the topic – strengthened with the guidelines from Chapter X.

To determine the arm’s length price of an intra-group financial transaction, the most common methodology is to search for comparable market transactions that share the characteristics of the internal transaction under analysis. For example, in terms of credit risk, maturity, currency or the presence of embedded options. In the case of financial transactions, these comparable market transactions are often loans, traded bonds, or publicly available deposit facilities. Using these comparable observations, an estimate is made on the appropriate price of a transaction as a compensation for the risk taken by either party in a transaction. The risk-adjusted rate of return incorporates the impact of the borrower’s credit rating, any security present, the time to maturity of the transaction, and any other features that are deemed relevant. This methodology has been explicitly incorporated in many publications including in the guidance from the South African Revenue Service (SARS)2 and the Administrative Principles 2023 from the German Federal Ministry of Finance.3

The recently published Corporate Tax Guide of the UAE also implements OECD Chapter X, but does not explicitly mention a preference for market instruments. Instead, the tax guide prefers the use of “comparable debt instruments” without offering examples of appropriate instruments. This nuance requires taxpayers to describe and defend their selection of instruments for each type of transaction. Although the regulation allows for comparability adjustments for differences in terms and conditions, the added complexity poses an additional challenge for many taxpayers.

A special case of financial transaction for transfer pricing are cash pooling structures. Due to the multilateral nature of cash pools, a single benchmark study might be insufficient. OECD Chapter X introduced the principle of synergy allocation in a cash pool, where the benefits of the pool are shared between its leader and the participants of the pool based on the functions performed and risks assumed. This synergy allocation approach is also found in the recent guidance of SARS, but not in the German Administrative Principles. Instead, the German authorities suggest a cost-plus compensation for a leader of a cash pool with limited risks and functionality. Surprisingly, approaches for complex cash pooling structures such as an in-house bank are not described by the new German Administrative Principles.

To find out more about the search for the best comparable, have a look at our white paper. You can download a free copy here.

Moving towards new credit rating analyses

Before pricing an intra-group financial transaction, it is paramount to determine the credit risks attached to the transaction under analysis. This can be a challenging exercise, as the borrowing entity is rarely a stand-alone entity which has public debt outstanding or a public credit rating. As a result, corporates typically rely on a top-down or bottom-up rating analysis to estimate the appropriate credit risk in a transaction. In a top-down analysis, the credit rating is largely based on the strength of the group: the subsidiary credit rating is derived by downgrading the group rating by one or two notches. An alternative approach is the bottom-up analysis, where the stand-alone creditworthiness of the borrower is first assessed through its financial statements. Afterwards, the stand-alone credit rating is adjusted with the group’s credit rating based on the level of support that the subsidiary can derive from the group.

The group support assessment is an important consideration in the credit rating assessment of subsidiaries. Although explicit guarantees or formal support between an entity and the group are often absent, it should still be assessed whether the entity benefits from association with the group: implicit group support. Authorities in the United States, Switzerland, and Germany have provided more insight into their views on the role of the implicit group support, all of them recognizing it as a significant factor that needs to be considered in the credit rating analysis. For instance, the American Internal Revenue Service emphasized the impact of passive association of an entity with the group in the memorandum issued in December 2023.4

The Swiss tax authorities have also stressed the importance of implicit support for rating analyses in the Q&A released in February 2024.5 In this guidance, the authorities did not only emphasize the importance of factoring the implicit group support, but also expressed a preference for the bottom-up approach. This contrasts with the top-down approach followed by many multinationals in the past, which are now encouraged to adopt a more comprehensive method aligned with the bottom-up approach.

Interested in learning more about credit ratings? Our latest white paper has got you covered!

Grab a free copy here.

Standardization for success

Although the standards set by the OECD have been explicitly adopted by numerous jurisdictions, the additional guidance further develops the requirements in complex transfer pricing areas. Navigating such a complex and demanding environment under increasing interest rates is a challenge for many multinational corporations. Perhaps the best advice is found in the German publication: in its Administrative Principles, it is stressed that the transfer price determination should occur before completion of the transaction and the guidelines prefer a standardized methodology. To get a head start, it is important to put in place an easy to execute process for intra-group financial transactions with comprehensive transfer pricing documentation.

Despite the complexity of the topic involved, such a standardized method will always be easier to defend. One thing is for certain: the details of transfer pricing studies for financial transactions, such as the analysis of ratings and the debt market, will continue to be a part of every transfer pricing and tax manager agenda for 2024.

For more information on Mastering Financial Transaction Transfer Pricing, download our white paper.

Citations

- Chapter X, transfer pricing guidance on financial transactions, was published in February 2020 and incorporated in the 2022 edition of the OECD TP Guidelines. ↩︎

- Interpretation Note 127 issued in 17 January 2023 by the South African Revenue Service. ↩︎

- Administrative Principles on Transfer Pricing issued by the German Ministry of Finance, published on 6 June 2023. ↩︎

- Memorandum (AM 2023-008) issued on 19 December 2023 by the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Deputy Associate Chief Counsel on Effect of Group membership on Financial Transactions under Section 482 and Treas. Reg. § 1.482-2(a). ↩︎

- Practical Q&A Guidance published on 23 February 2024 by the Swiss Federal Tax Authorities. ↩︎

SAP Treasury’s Strategy for Seamless Compliance worldwide

In the first half of 2024, European treasurers are confronted with a new item on their agenda: the updated EMIR Refit. The new EMIR reporting rules will be implemented in the EU on the 29th of April 2024, and in the UK on the 30th of September 2024.

The Updated EMIR Refit introduces the following main changes:

- Harmonizing the reporting formats to ISO 20022 XML

- Increasing the number of reporting fields from 129 to 203 (204 in the UK)

- Introducing new fields: UPI (Unique product identifier) and RTN (Report Tracking Number)

For more details about these changes, refer to this article on the implications of the EMIR Refit.

Trade repository reporting in SAP Treasury and Risk management

SAP Treasury users inquire on how to deal with the changes in their solution, what comes out of the box, what adjustments are necessary,and where the challenges are.

Since the introduction of the original EMIR reporting in 2012, SAP has covered the requirements for EMIR reporting in the component Trade repository reporting. It is a robust functionality fully integrated into the SAP Transaction manager environment. Due to varying requirements among the various trade repositories, SAP has ceased to enhance the solution and referred clients to the partner solution of Virtusa. However, the SAP Trade repository solution (“TARO”) is still supported on all current releases in the existing functional extend and can be used and adopted by in-house developments and consulting partners (SAP Note 2384289). Using the Virtusa solution or a custom solution, with EMIR Refit, a number of new required fields needed to be incorporated into the deal management data model.

The following changes have been provided by individual SAPNotes over the course of the past months:

- Unique Product Identifier (ISO 4914 UPI) and Report Tracking Number (RTN) have been introduced. They are available under the tab “Administration” in the deal data.

- These fields have been introduced to the relevant BAPIs, mirror deal functionality, as well as to the SAP TPI interface.

New reporting fields

The EMIR Refit solution utilizes fields, which have already been made available earlier, over the course of the original EMIR Refit in 2018 (Switch FIN_TRM_FX_HMGMT_3), and are present also under the tab “Administration” for the relevant product categories:

- CFI Code (Classification of Financial Instruments, ISO 10692 Classification)

- ISIN on the deal level for OTC deals

- Market Identification Code (MIC)

The recently introduced field is the UPI, which is a classification assigned by ANNA Derivatives Service Bureau. It consists of 12 characters and reflects both the Asset class, Instrument type, Product and the CFI. The CFI itself is an instrument classification which is 6 characters long.

The next consideration is how to populate these fields. In case of external trades, the CFI and UPI can be delivered by the trading platform. SAP Trade platform integration (TPI) covers the transfer of these fields from the trading platforms.

Since 2019, in case of OTC deals, EMIR Refit made financial counterparties (FC) solely responsible and legally liable for reporting on behalf of both counterparties, provided the non-financial counterparty is below the clearing threshold (NFC-). Therefore, this option would be necessary only for large financial entities, as smaller corporates are not obliged to report external OTC deals, as the counterparty reports on their behalf.

Corporates are obligated to report their intercompany deals, under the condition that they cannot apply for an opt out with their regulator. In that case, the CFI and UPI need to be derived in-house.

For that purpose, there are enhancements (BAdIs) available, to implement one's own derivation logic.

The reporting format has been standardized with ISO 20022 based XML. XML output can be easily generated based on a DMEE structure. Unlike the original version from 2012, SAP does not deliver the new report structures needed for the EMIR Refit. This part needs to be set up in a project.

The impact of the EMIR Refit in the trade repository reporting of your organisation can bring up many specific questions. We are happy to help you answer them from both the advisory as well as the technical implementation point of view. Examples on how Zanders can assist is:

- Implementing the new Emir Refit requirements in SAP Treasury

- Assisting in applying for the exemption of reporting internal trades with the various regulators

Reach out to Michal Šárnik to receive assistance on this topic.

Collaboration, trust and growth, how we’re celebrating 25 years of partnership with the market-leading technology platform.

Our technology partnerships are core, foundational elements of our risk and treasury transformations at Zanders. For us to guide our clients through their digitalization journeys and keep pace with technology advancements relies on the right relationships (non-commercial of course, so we maintain our independence) with the best solution providers in our field. To stand the test of time, these relationships need to be mutually advantageous, and this takes both parties to be engaged, committed to continual learning, and driven by a shared vision. Our work with SAP embodies these qualities. And in demonstration of the success of this alliance, in 2024 we’re celebrating 25 years of partnership with the market-leading technology platform.

To mark this anniversary milestone, we invited Christian Mnich, VP, Head of Solution Management, Treasury and Working Capital Management at SAP to join Zanders partners Judith van Paassen and Laura Koekkoek to reflect on how the relationship has developed in this time. As they shared anecdotes and considered the unique characteristics that have shaped this partnership, three key themes emerged – collaboration, trust, and growth.

1. Collaboration: A meeting of minds

From day one, there was an enthusiasm from both companies to collaborate and share expertise. Zanders’ first encounter with SAP was at a trade fair in 1998. Back then, Zanders was four years young and a relative newcomer to the treasury advisory world. SAP was an established standard in business processing software but at this point still a single-product, ERP solution. As the modern technologies lead for Zanders, Judith van Paassen visited the SAP stand at the exhibition curious to see how the platform could extend to support the work Zanders was doing with corporate treasury departments.

“SAP was present at that fair with an early version (2.2F) of the system,” Judith recounts. “I asked some in depth questions at the time about functionalities. Can SAP do this? Can SAP do that? After some further discussion and exchange of knowledge, the idea to join forces was brought up.”

On the basis of this trade fair encounter, SAP and Zanders together started looking into how the system could be customised for treasury, specifically at the time for the Dutch market.

2. Trust: The backbone of successful partnership

The partnership initially focused on the Netherlands, with Judith regularly spending time with SAP colleagues, working with the team on how to position the treasury system to the market and helping them to demonstrate the potential of the solution to support corporate treasury processes.

“It was a very close partnership between the Netherlands and Zanders – where Zanders and SAP worked closely together and were organizing seminars to inform the market on the capabilities in SAP,” Christian remembers. “This model was very unique back then and the partnership model is still working very well for SAP and their partners.”

These early days formed a backbone for the partnership, embedding a commitment to honest and open collaboration into the core of the relationship.

“It’s all been built from trust,” Christian emphasizes. “When building a long-lasting partnership, you need to have open dialogue – on both sides. It’s very important to us as a solution provider that when we roll out new solutions, we get honest feedback. We’ve had lots of sessions with Zanders over the years where you’ve provided this honest feedback. By doing this, you’ve helped us to scale our solutions, develop new solutions and increase the adoption of our services.” “This also comes back in our co-development of regional solutions for local requirements like the connectivity between eBAgent and MBC in the APJ region” says Laura.

3. Growth: Pioneering new environments

As the partnership has expanded from the Netherlands and Benelux to the UK, parts of the DACH region, the US and APJ, it has provided a launchpad for important growth opportunities for both businesses. For Zanders, it’s empowered our team with a much deeper understanding of the role and potential of innovation in our market, enabling us to take a proactive role in guiding our clients through transformation projects.

“We’re consultants – we like to give advice to our clients – but we also really want to implement solutions with our clients,” says Judith. “To do this, we need to not only look at the little details within treasury, but at the end-to-end process and architecture. Our knowledge of treasury in combination with our experience with SAP technology has definitely made us more attractive to expand our services to clients in Asia, the US and APJ. It’s has also allowed us to take a more proactive role in driving large-scale treasury transformations for our clients.”

Christian agreed that the partnership has also been an enabler of growth for SAP, highlighting three transformation projects undertaken jointly by the partnership as key moments:

- Firstly, AkzoNobel. It was the first treasury transformation the partnership worked on where SAP was implemented to replace a best of breed TMS system in the European environment. The size and complexity of this project made it a blueprint for future transformations. In particular, demonstrating the benefits of breaking down product siloes to add treasury capabilities to the SAP ERP system in a more integrated way.

- Secondly, BP. Although not as large and extensive as other projects, it’s notable for its strategic importance. This project represented the first entry into the UK for SAP, paving the way into an important growth market and opening up new opportunities in other regions.

- Thirdly, the implementation of the SAP S/4HANA treasury system for Sony. As a truly global transformation project, the scale and nature of the project (especially given the timing with the pandemic) meant there were many challenges. The success of the deployment is a testament to the strength of the partnership, with the teams working together closely to develop the best solution for the client.

Together, these projects show the relentless commitment from both partners to challenge boundaries, see the bigger picture and prioritize client needs.

“We’ve seen a willingness from Zanders to expand their view from core treasury into other areas,” Christian explains. “This is very important for us from an SAP point of view. Smaller, niche or more boutique partners – they don't leave their comfort zone, whereas there's always interest from Zanders to learn new things. We appreciate how you try to understand the challenges before your customers run into these challenges.”

25 years – A celebration of collaboration, trust, and growth

What our 25 years working with SAP shows us is the success of our partnership comes down to how we work together as a team. This means trusting each other, being collaborative, and relies on both parties being willing to challenge the status quo to pursue ambitious growth. What SAP and Zanders have accomplished together already may have been ground-breaking, but it feels like we’ve still only just scratched the surface of what we can potentially achieve together. For this reason, our journey together will continue long into the future – at pace.